The Funny Papers

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, before I was old enough to get a work permit, I delivered newspapers in my suburban Philadelphia neighborhood. You might say it was my first job in publishing. At the time, Philadelphia was a three-paper town: There was the Inquirer, the Bulletin, and the tabloid Daily News. Where I lived, we also had a local paper, the Norristown Times-Herald.

First, I delivered the evening Bulletin (its slogan: “In Philadelphia, nearly everybody reads the Bulletin”) daily and Sundays. It was heavy with advertising, especially on a week leading up to a holiday, and I would pile the papers on a Radio Flyer wagon that I hauled up and down the streets like an undersized tugboat pulling a coal barge upriver. If the weather was especially rotten, my sainted mother would drive me around in the family station wagon. But I was usually on my own — come wind, rain, or snow. After two years humping the Bulletin, I jumped at the chance to deliver the much thinner Times-Herald. The route was smaller, there was no Sunday edition, and it actually paid better. I did that until I landed a job bagging groceries at a local supermarket.

Looking back, being a paperboy was a formative experience. I earned decent money for a 14-year-old; I learned how to sell subscriptions and keep payment records; I got to meet the neighbors (and their daughters). But above all, I got to see the funnies before anybody else. I would cut open the bundle, fish out a fresh copy, and settle back for some chuckles and thrills before heading out on my route.

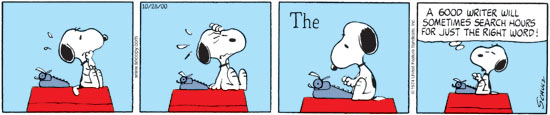

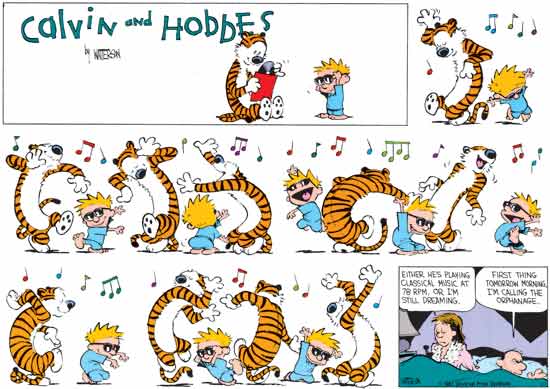

It was then that I fell in love with comic strips in all their glorious variety — humor, adventure, romance, you name it. I had favorites — Peanuts, Prince Valiant, Pogo, The Phantom, Blondie, Li’l Abner — but I would also get caught up in the soap operas unspooling in the likes of Brenda Starr, Mary Worth, and Rex Morgan, M.D. Over the years, some old favorites faded away, as did the Philadelphia Bulletin, but inventive new strips like Doonesbury, Calvin and Hobbes, Bloom County, and Mutts arrived on the scene and took the comics in wonderful, sometimes challenging, directions.

Today, wherever I am, I still open the paper to the “funny pages” first thing to start my day with a smile. But I am in increasingly diminished company, as newspapers have consolidated or shut down across the country and readership has dropped dramatically. The numbers tell the tale: In 1960, there were 1,763 total daily newspapers (morning and evening) with a total circulation of 58,882,000; in 2014, there were 1,331 with a total circulation of 40,420,000. Meanwhile, average daily newspaper readers are now in their mid-50s and getting older. And reading the newspaper is not a habit with younger generations, who prefer to get their news online (ironically, often at newspaper websites) or via social media like Facebook or Twitter. Even some of my own contemporaries tell me that they don’t read the print newspaper. “Print, how quaint,” they sniff.

Despite such chattering, I believe we can say with assurance that print is definitely not dead and newspapers will endure, albeit as less of a fixture in daily life than in years past. But what do these demographic and digital changes bode for the comics, an indigenous American art form that has entertained hundreds of millions of readers — including me — since the turn of the 19th century?

I set out to ask some folks who would know.

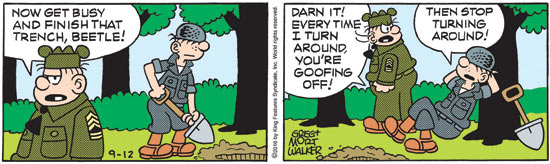

If there’s such a thing as comics royalty, Brian Walker is it. His dad, Mort Walker, created Beetle Bailey in 1950 and is still penciling it at age 93. The perennially popular strip set in Camp Swampy and starring the goof-off private and his nemesis Sergeant Snorkel currently appears in 1,800 papers around the world. (Fact: Like many young artists in the late ’40s and early ’50s, Mort Walker contributed gag cartoons to The Saturday Evening Post before gaining fame with his comic strip. Beetle himself was named after Saturday Evening Post cartoon editor John Bailey.)

The younger Walker is also a historian, the author of The Comics: The Complete Collection (Abrams ComicArts), an indispensable and authoritative (and big!) survey of the strips and artists who have delighted readers from the 1890s to the 21st century, from The Yellow Kid and Little Nemo in Slumberland to Zits and Pearls Before Swine.

—UClick’s John Glynn

In The Comics, he makes a compelling case for the comics as a singular art form, writing, “Cultural elitists relegate comics to the status of ‘low art.’ Cartoon art should not be judged by the same criteria as fine art. Comics are a unique visual and narrative art form, and both elements should be considered when evaluating the work of an individual cartoonist. Comic creations are also the products of the culture within which they are produced. All these factors must be taken into account when developing an appreciation for cartoon art.”

Finally, he’s a cartoonist in his own right, collaborating since the early ’80s with his brother, Greg Walker, and other artists on Hi and Lois, which was created by Mort Walker and the late Dik Browne (Hägar the Horrible) in 1954 and appears in 1,000 papers today. (Fun fact: Hi and Lois Flagston are Beetle Bailey’s sister and brother-in-law.)

So, you take him seriously when he says, “I wouldn’t recommend newspaper cartooning to an aspiring artist — it’s not a growth industry.”

Indeed, with circulation declining and more and more readers getting their news online, print newspapers nationwide have been allotting less space to the funnies. That and canceling strips that don’t score well in reader polls. In a few instances, even the venerable Beetle Bailey has been dropped as struggling newspapers fold or cut costs by eliminating older, more established (and more expensive) strips. Meanwhile, Walker explains, the major syndicates that distribute comic strips are paying “next to no money” to new artists. “They’re practically giving away new strips,” he says.

At the same time, syndicates like Universal Uclick and King Features are putting their comics online for the enjoyment of the millions of fans who don’t read print newspapers or can’t get their favorite strips in their local paper. “The internet changed the game,” Walker says. “The syndicates were rather slow to jump on the web, thinking their newspaper clients would be upset. They’ve since gotten savvier about expanding their presence in social media with sites like GoComics.com and ComicsKingdom.com, blogs, and Facebook.”

Asked to put on his historian’s hat and name a Golden Age of comics, Walker points to the ’30s and an “explosion of creativity” that brought about such classics as Flash Gordon, Dick Tracy, Prince Valiant, Popeye, Blondie, and Li’l Abner. The decade is also memorable, he says, for the rise of the adventure strip with its long-running story lines and danger-defying heroes (e.g., Terry and the Pirates and Mandrake the Magician) that delivered thrills by the panel-full over the years.

Walker then fast-forwards five decades to the emergence of the baby-boomer artists of the ’70s and ’80s who ushered in a “renaissance” of comics art. “The new generation was inspired by Charles Schulz’s multidimensional characters,” he says. Although children, Charlie Brown, Lucy, Linus, and the rest of the Peanuts crew grappled with such adult, existential issues as loneliness, disappointment, failure, and loss. With the massive success of Peanuts, Schulz established that a cartoonist could examine the darker aspects of everyday life and still provoke a smile. For the Me-Generation cartoonists, this was a clarion call: What better life to examine than your own? And the time was right for a new approach. “Tastes had changed,” explains Walker. “Readers wanted to see themselves and their experiences in the strips. In the classic era, the artist was in the shadows, behind the scenes; the boomer artists were more autobiographical. When you read strips like Doonesbury, Cathy, Dilbert, and For Better or Worse, you were getting a glimpse into the lives of the artists.”

The new comics cadre also catered to the irreverent, anti-authoritarian spirit of the times with unconventional, envelope-pushing strips like the (sadly) short-lived The Far Side, Bloom County, and Calvin and Hobbes, this last chronicling the adventures of a wildly imaginative 6-year-old boy and his stuffed toy tiger. “If pressed to name the best comic strip of all times,” Walker says, “I’d have to say Calvin and Hobbes. It works on so many levels.” Indeed, aside from Peanuts, no modern strip has had such an influence and won such acclaim.

Hi and Lois, on the other hand, has been a quiet success for 62 years, as the immutable Flagstons navigate life in suburbia together. With its gentle life lessons and G-rated humor, Hi and Lois offers a sweet counterpoint to the snark and surreal antics of newer strips. “They’re a functional family in a dysfunctional world,” Walker says. “I get nice letters from mothers.”

In the Flagstons’ world, things change over time without really being that noticeable (with the exception of Chip aging into a teenager). “We now have computers, cellphones, flat-screen TVs, and things like that,” Walker explains, “but that’s just the background.”

The one thing sure to never change is the bond between the family members, which can be difficult to capture in a couple of panels. “It’s challenging to show love in a strip,” says Walker, who credits The Family Circus creator and friend Bil Keane with being an inspiration. “He gave me the courage to do things that are sweet and loving.”

But while the Flagston world may change incrementally, Hi and Lois itself has embraced the digital age. There is a Hi and Lois website (HiandLois.com), which attracts thousands of visitors a week with new strips, a weekly blog by Walker, and access to an archive of decades of vintage strips. And these days, the classics must maintain a presence on social media: both Hi and Lois and Beetle Bailey have Facebook pages boasting more than 2,500 likes each.

In another telling sign of the times, Walker’s own comics-reading habits have changed. “I buy the Sunday paper,” he reports, “but for daily comics, I go online to the syndicate sites where I can keep up on strips that never run in my local paper.”

© Bill Watterson, reprinted by permission of Universal UClick, All rights reserved

Asked about the condition of the newspaper comic strip today, King Features Syndicate Editor Brendan Burford paraphrases Mark Twain’s famous line: The report of its death was greatly exaggerated.

Yes, he acknowledges, print has been in decline, but “there’s no reason to think because there’s a contraction in newspapers that people are going to stop reading and enjoying comics. Overall, our business has been stable.”

Launched in 1915 by legendary publisher William Randolph Hearst, King Features is the second-largest comics syndicate after Universal Uclick. It currently syndicates 62 comic strips to newspapers worldwide and maintains an extensive archive of vintage strips on its website, ComicsKingdom.com. The King Features roster runs the funnies gamut: from boomer faves Mutts and Baby Blues to such old-school stalwarts as Mary Worth and Mark Trail — along with some of the biggest titles in the business. “The number of comic strips we license to more than a thousand clients — strips like Dennis the Menace, Hägar the Horrible, Family Circus, Beetle Bailey — is remarkable,” Burford says. “That’s rare air.”

Still, growth is hard to come by, especially in newspapers, where King Features is competing for space with other syndicates. “Our newspaper clients want something fresh,” says Burford, who has seen tastes change in his 15 years at the syndicate. Adventure comics are on the wane, as readers get their escapist satisfaction in comic books, television, and movies. “People now want to see themselves and their friends,” he says, echoing Brian Walker. “They want a reminder that life has levity.” To prove the point, he cites the enormous popularity of Zits, which features the foibles and fantasies of teenager Jeremy Duncan — and the reactions of his often perplexed parents. “It’s a reflection of today’s family.”

To find that “something fresh” for his clients, Burford sifts through “thousands of submissions” from would-be syndicated cartoonists every year. Sadly, of those few that show promise, he says, “I can only run with one or two” in today’s tight market — which can be frustrating for a syndicator. “I wish we could represent all the talent we like.”

As for the 62 active strips it does represent, King Features has assembled the whole batch, along with a library of vintage comics, on the web at ComicsKingdom.com. For fans of the funnies, this is liberating stuff. No longer get Crankshaft or Judge Parker in your local paper? You can catch up with them online. Or browse past installments of classics like Krazy Kat, The Katzenjammer Kids, and Popeye. Even better, you can subscribe to the site and have your favorite strips emailed to you daily.

Over at rival syndicate Universal Uclick, President and Editorial Director John Glynn remembers being told in 2000 that there “wouldn’t be newspapers by 2010.” Nearly seven years past that deadline, the largest independent syndicate in the world represents more than 80 active comic strips in approximately 2,000 papers worldwide, including such legendary strips as Garfield, Doonesbury, Peanuts, and Dilbert — all of which appear in thousands of newspapers around the world — plus offbeat hits like Pearls Before Swine, Foxtrot, and Get Fuzzy. “Newspapers will be here, one way or another,” says Glynn, “and it wouldn’t be a newspaper without comics.”

Universal Uclick also runs a website, GoComics.com, where funnies fans can browse day-of-publication installments of Universal Uclick’s active strips, plus an archive of such classics as Peanuts, For Better or For Worse, Dick Tracy, and Alley Oop. One of the beauties of the web, he says, is “there is no limitation to the real estate.” Which makes it possible for them to distribute some 400 strips digitally. (In a bit of irony, they syndicate comics to newspaper sites looking to improve on their limited print offerings. “They can carry as many as 40 to 60 strips online with us,” Glynn says.)

In Glynn’s view of the future, “newspapers will hang on” while the funnies will continue to find new markets. “We’ll deliver comics to wherever people are reading them,” he says, “be it newspapers, desktops, tablets, or smartphones. I’m a big believer in the medium,” Glynn says, “I think of them as ‘snackables’ that brighten the day.”

Glynn might have had Pickles in mind. The award-winning, G-rated, gag-a-day strip that celebrated its 25th anniversary in 2015 is a welcome tonic in trying times. A former graphic designer turned cartoonist, Pickles creator Brian Crane takes a sweetly wry look at the lives of 70-something retirees Earl and Opal Pickles and their family and pets. Married 50 years, Earl and Opal have learned to (sometimes grudgingly) accept each other’s quirks as they grow old together, while imparting their accumulated wisdom and humor to the younger generations.

Looking back, Crane considers himself lucky to be where he is today. “I was a long shot to get syndicated,” he says. “You’d get better odds at a racetrack.” Nevertheless, the 40-year-old novice had encouragement on the homefront — “my wife kept pushing me to submit my work” — and after only three rejections, he was a syndicated cartoonist, right in the midst of what was allegedly an imploding market for newspaper comics. “That’s what they told me in 1990, and papers have gone out of business on me,” he says. “But I’ve weathered the storm pretty well. I’m almost always on top of reader polls, and I’m closing in on 1,000 papers.”

Not surprisingly, the Pickles readership skews older — but not exclusively. “When I speak at events,” Crane says, “there’s a lot of gray hair in the audience, but I do well with younger folks in reader polls.” How to account for the strip’s multigenerational appeal? “I’ve heard it from folks a thousand times,” says Crane. “They tell me, ‘You must have a microphone hidden in our home!’” It doesn’t hurt that Crane maintains a strong digital presence. Pickles is carried online by GoComics.com/Pickles and ArcaMax.com, where it is enjoyed by tens of thousands of fans. And the Official Pickles Comic Page on Facebook — which posts the daily strip, past favorites, videos, reader comments, and personal shares — had amassed more than 34,000 likes at last count.

Crane’s hero is Charles Schulz, whose approach to Peanuts and life Crane admires. “He was humble and kind,” he says. “He never went the easy route, never coasted.”

It’s an ideal that Crane tries to follow in a hyper-competitive business. “I can’t rest on my laurels,” he says. “My daily challenge is to be funny today. I keep trying to surprise myself, looking to find things in my own life that spark ideas.” He doesn’t have to look all that far: With seven children and 11 grandchildren of his own, Crane literally inhabits the world of doting — and occasionally dotty — grandparents Earl and Opal Pickles.

There has always been an underlying purpose to Pickles, Crane says, which is “to point out that being older is a good time to be alive; to laugh at the foibles of growing old.” And, today, 26 years after breaking into the comics business, he wouldn’t change a thing about his own life: “From my myopic point of view, it’s a nice situation for me. I write something that makes me happy.”

Like Brian Crane, Pearls Before Swine creator Stephan Pastis ditched a paying career to follow his dream. Unhappy with practicing law in the San Francisco Bay area in the mid-’90s, he decided “I have to do something else” and began cartooning. Pastis studied Dilbert to learn how to write a three-panel strip. In a bold step, he approached Charles Schulz himself at a Northern California skating rink coffee shop and asked for advice. (Schulz was gracious and helpful.) He also recruited Darby Conley of Get Fuzzy fame for input on coloring the artwork. After submitting various strips “five or six times” to syndicates, he clicked with Pearls Before Swine, which debuted online in 2000 in a test by United Features Syndicate, and then in newspapers on December 31, 2001. In 2002, he quit his day job and became a full-time cartoonist.

Today, Pearls Before Swine is carried by 750 papers worldwide and growing. The strip (gocomics.com/pearlsbeforeswine) chronicles the exploits of Rat, Pig, Goat, Zebra, and a crew of delightfully dimwitted Crocs who speak with a mysterious, unidentifiable accent. Regular targets of his snarky humor include vegans, bikers, other strips (e.g., Cathy, The Family Circus), and sometimes even Pastis himself. Often controversial for its adult humor and eagerness to test the boundaries of propriety (is that a swear word I see?), Pearls Before Swine has nevertheless won the National Cartoonists Society’s Best Newspaper Comic Strip award three times and been nominated eight times for the Reuben Award, the society’s highest honor. “You’re not artistic or creative if you’re not pushing the boundaries,” he says.

Part of the secret is being true to himself. “If you write honestly, your body of work reveals who you are,” he says. “If you’ve read the strip faithfully for 15 years, you know me as well as my relatives.”

It’s a successful approach that no longer relies on newspapers alone. Cartoonists today need to diversify and self-promote relentlessly. “To be famous these days, you have to be famous in a number of piles — newspapers, books, music, cable, social media,” Pastis says. “Everybody is hustling harder, even a superstar like Bruce Springsteen has to do a lot more promotion than he did in the ’70s.” There are 18 Pearls Before Swine collections and eight treasuries, plus merchandise (T-shirts, mugs, plush animals, etc.), and Timmy Failure, a best-selling series of chapter books aimed at middle schoolers. The Stephan Pastis Facebook page has upwards of 154,000 likes as this article goes to press. “It’s a revolution,” he declares. “The winners will adapt. With the internet, you now have the ability to address people directly and react to events quicker. I have more fans in Mumbai than in any other city in the world.”

Of course, all the marketing and promotion in the world won’t sell your work if it doesn’t strike a nerve. A sociologist might say the secret to the success of Pearls Before Swine lies in Pastis’ ability to tap into the current snarky zeitgeist using angry Rat, naive Pig, bookish Goat, even the inarticulate Crocs, as his stand-ins. The artist himself makes no such claim, suggesting instead, “It’s sheer, dumb luck it worked.”

I’m sure Rat would disagree.

As a lifetime fan of the funny pages, I’m gratified that many of the great ones continue to thrive. As Brian Walker writes in The Comics, this particular art form has endured because the funnies have timeless appeal. “Their daily appearances make them familiar to millions. Their triumphs make them heroic. Their struggles make them seem human. Cartoonists create friends for readers. Pogo, Peanuts, Calvin and Hobbes, and Dilbert are part of a great cultural legacy that is being further enriched every day. The final panel has yet to be drawn.”