The Truth (at Last) About Disco

Mention the word discotheque, and most people think of the 1970s — the Bee Gees, Donna Summer, John Travolta, and Saturday Night Fever.

In fact, the disco trend began early in the previous decade, and it changed the way America danced.

Until the late 1950s, social dancing was a fairly formal arrangement. Dancers maintained some physical contact with their partners and engaged in synchronized footwork. If you were a guy who hadn’t learned much about dancing, you could rely on the utilitarian box step (if the music was in four four time) or a basic waltz (a three four rhythm). If you were a girl, you followed your partner’s lead as you danced backward across the floor, pulling your feet away from your partner’s approaching tread.

As rock ’n’ roll started to gain popularity, teens danced to the new sound with swing dances like the Lindy Hop. There was also the Stroll, the Bop, or the Madison. Dancers no longer held onto each other, but their feet moved in unison to established steps.

Then came the hip-swiveling Twist, made popular in 1960 by Chubby Checker. Suddenly dancers were on their own, doing — to use a popular ’60s phrase — “their own thing.” Soon discotheques were popping up across the country.

Writing for the Post in 1965, Norman Poirier described the discotheque scene as “a noisy national madness that the anthropologists of the 21st century will find difficulty in explaining.”

The discotheque, he wrote, had originated in France where the word meant “record library.” He claimed the first discotheque was the Whisky a Go Go in Paris, “where members could dance to records and consume whiskey, a drink many Frenchmen then regarded as exotic.” The term go go, he added, was French slang, that roughly translated to “as much as you want.” The French word for disc jockey, disquaire, never made it across the Atlantic.

By the time Poirier wrote his article, nearly every [major] American city had a “go-go” of its own.

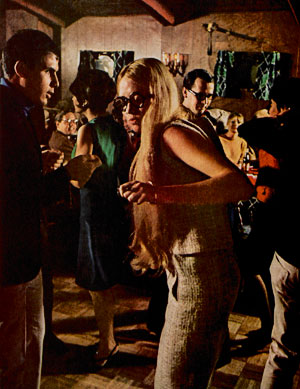

Americans entering a discotheque for the first time in the early ’60s would have noticed the absence of musicians. The management used only recorded music, played continuously. And loud. The sound seemed almost deafening to people accustomed to live bands.

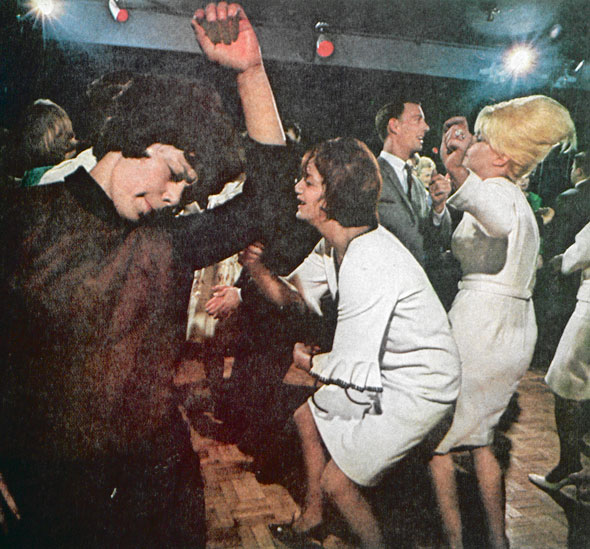

They would also have been surprised by the wide variety of individual dance styles. The Twist had spun off several varieties of new dances. Poirier listed some of the better known styles: the Watusi, Hully Gully, Surf, Swim, Dog, Pony, Ska, Frong, Wobble, Slop, and Jerk.

It could have all seemed strange, noisy, and very modern. And to some newcomers, it might have seemed more than a little decadent. The dancers seemed so frenetic and uninhibited. Many grown-ups looked on in astonishment. What were the kids up to? Why had they abandoned the grace and sophistication of ballroom dances?

“There’s no mystery why anyone is doing these dances — they’re fun,” dance instructor “Killer Joe” Piro told Poirier. But he later admitted they weren’t fun for men who felt awkward and uncomfortable with new steps. “Even when we’re alone in my studio, they feel self-conscious. They giggle when I say wiggle. They won’t relax. They’re all tied up. Men are really more scared about how they look than women.”

Men may have felt inhibited by the new, more expressive style of dancing, but their partners weren’t. “The girls really love these dances,” said Piro. The way he described the discotheque phenomenon, it almost sounds like the harbingers of the modern feminism — a new “women’s movement,” you might say.

“The girl is free to do what she wants to. She couldn’t let herself go before the Twist. They must have been swearing under their breath for years — led around, pushed around, held down. Now they can be as wild as they feel. Watch any discotheque and you’ll see it’s the girls who go. On the dance floor they’ve got no inhibitions!”

Men would learn to overcome their self-consciousness. They’d learn the new steps because, like Piro, they realized that if they were going to get any girls, they’d have to Shag and Frug with the rest of the “in” crowd.