Second Chapters: Still Life After Death

Norm Diamond’s 30-year career as an interventional radiologist required intense precision daily. The ever-changing technological landscape of the field kept Diamond on his toes as he treated a wide variety of diseases with minimally invasive techniques. For example, he describes a procedure in which he used a catheter the size of overcooked angel hair pasta to patch a bleeding artery. Dyes, stents, and imaging technology were among the tools Dr. Diamond used until retiring in 2012. Then he took up a different set of tools: lenses, lights, and tripods.

His second chapter got its start in 1979 when he captured an image of a Holocaust remembrance plaque in Paris. The plaque, at the School of Hospitalières-Saint-Gervais, reminds pedestrians of the 165 Jewish children taken from the school to Nazi concentration camps during World War II. N’oubliez pas, the plaque reads — “Do not forget.”

Others recognized the beauty and pathos of Diamond’s photograph of the plaque with two children playing in the foreground. It was acquired by Holocaust museums in Paris, Jerusalem, and Dallas.

Diamond continued taking pictures as a hobbyist, but after retiring from medicine, he devoted himself to the art form, using it as a way to reflect on his emotionally taxing career. He cites the evocative photography of Cig Harvey, Jay Maisel, and Debbie Fleming Caffery as influences on his work. He found his own muse in the storytelling capacity of everyday household articles.

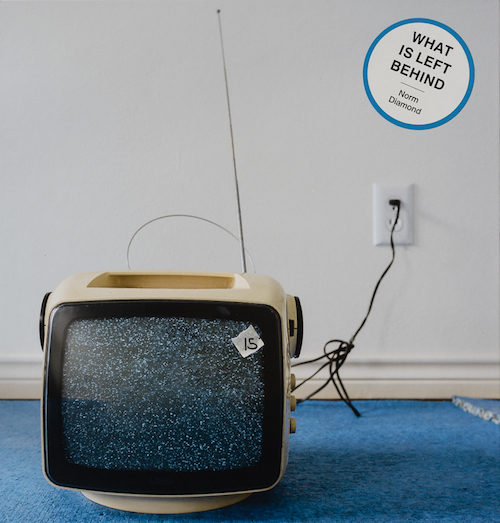

Diamond’s book, What Is Left Behind: Stories from Estate Sales, features 66 photographs he captured while visiting hundreds of estate sales around Dallas over the course of a year. The photos display poignancy, humor, and often a Texas flair. Diamond was drawn to photograph estate sales because of the unique emotional magnitude of each object he encountered. In the preface of his book, Diamond says, “The stark reality of life’s brevity pervades every estate sale, where children’s toys sit a few feet from wheelchairs.”

Like a prepped patient, an estate sale is a life splayed open and on display. Items that presumably held considerable significance at one time can be found for $2.50, like the framed portrait in Diamond’s image “Man of the House.”

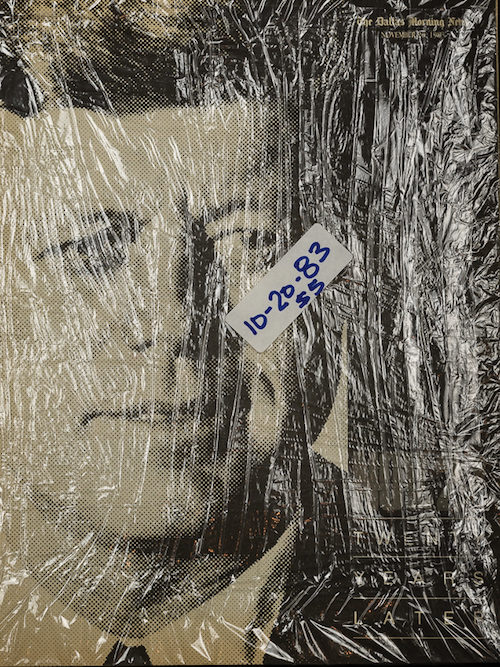

Diamond explores the emotional nature of objects in his collection. His stills capture history. Some are personal, like “Wedding Night Negligee,” and others are more public, like “Twenty Years Later,” a shot of an issue of The Dallas Morning News commemorating JFK’s assassination that someone kept for decades. “The themes of generational passage and the poignancy of aging are what moves me. My ancestors came to this country in the late 19th century, and they were more interested in becoming Americans than they were in recounting their past. That genealogy was never really passed down to me,” Diamond said.

Diamond believes his second career as an art photographer has been informed by his experiences in medicine. In his training to become an interventional radiologist, he was taught to suppress any emotional expression with his patients. This was best for the patient as well, he said. But Diamond believes this professionalism has affected his own relationships and given him a dark worldview. “The work was very consuming. It was something that occupied all of my attention, even when I wasn’t there.”

Through his photography, Diamond hopes to inspire others and to heal himself: “My images appeal to certain people. They move certain people, and that, to me, is a very gratifying thing.” The journey through time offered by his snapshots of discarded trinkets is sometimes mournful and sometimes droll, but it is always compelling. If objects could speak, these would have a great deal to say. Much like his first successful photograph, Diamond’s work has a running theme of paradoxical nostalgia and the emotional bearing of the inanimate as it seems to say, “Do not forget.”