North Country Girl: Chapter 6 — A Very Ratty First Communion

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir. The Post will publish a new segment each week.

For my semi-devout Catholic father’s sake, my skeptic mother gamely took meat off the menu for our own Friday dinners, which I made a trial for her, as I couldn’t stand cheese or eggs or fish. Pancakes were my Friday dinner of choice.

Eating meat on Friday was a mortal sin, as I learned in my catechism class, which I had to attend every Wednesday afternoon, along with a handful of other Catholic kids who didn’t go to parochial school. The class was held at Holy Rosary School, where frightening nuns in full habit prepared us to make our First Communion by drilling us with the Baltimore Catechism. We went over and over questions such as “Why did God make you?” until we could parrot the word-perfect answer: “God made me to know Him, to love Him, and to serve Him in this world, and to be happy with Him forever in the next.”

The nuns hated everyone in the catechism class. We were practically heathens; good Catholic children went to parochial school. The nuns assured me that I was not going to heaven as I did not have a saint’s name, and that my mother wasn’t going to meet St. Peter either, as she wasn’t Catholic. I was pitched into existential despair by this knowledge. It was also bone-chilling to have to make my first confession, required before taking communion. I had to learn yet another series of correct responses to questions I didn’t understand before I could enter the dark, velvet-curtained booth to make my confession. I knelt in the dim light until I heard the swoosh of the screen sliding back; even then the priest’s face was blurred through wavy plastic panels that were punctuated with holes so we could hear each other. I had to confess my sins, sins that I pretty much made up. I was seven years old. I didn’t steal, I didn’t lie, I didn’t take the Lord’s name in vain. I mostly did exactly as I was told. Did fighting with my sister count?

Having gotten that horrible ordeal over, I made my First Communion on a gloomy, rainy April Sunday, wearing a frilly white dress and a dainty veil bobby-pinned to my head, like a tiny bride. My Catholic grandmother made a big fuss over me, and gave me a small white missal with brightly colored illustrations of gospel scenes, and a pink and gold watch.

After that endless mass (dozens of little communicants lined up at the rail, all of us terrified lest we drop the Host out of our mouth and onto the floor, which according to the nuns, went so beyond a mortal sin that death by lightning was to be expected), our family went to breakfast at Perkin’s Pancake House, a huge treat, as it was always jam-packed on Sundays, and my father hated to wait for a table anywhere. Because I had to fast for two hours before taking communion, I was starving. Alas, the chocolate chip pancakes I always craved were still forbidden, even on the occasion of my First Communion; not by the Church but by my dentist dad who viewed them as candy for breakfast.

When we came back to our house, our happy, blessed party was greeted with a rat infestation. Duluth is a port city, built on a hill, and snowmelt and steady rains must have driven the rats up from the lake all the way to our “nice” neighborhood. My most vivid recollection of that day is not receiving the body of Christ for the first time, but watching my grandfather, the great hunter, beat a rat to death with a shovel. Poison was set out, and for the next few weeks I had to check carefully when I went down into my dad’s basement workroom to play with my Creepy Crawler set to make sure I didn’t step on a dead rat.

I loved my Creepy Crawler set; I squeezed bottles of red or blue or green liquid plastic into metal molds in the shape of insects, and then inserted the molds into a heater to set them. There was a flimsy wire handle to remove the red-hot molds, and a prescribed time to wait before peeling your new insects out of them, but burnt fingers inevitably ensued. To my great joy, my sister Lani was expressly prohibited from playing with my Creepy Crawler, or even being in the workroom while I used it.

Toys were plentiful, arriving as birthday presents and from Santa. Each December brought the thrill of new toys from Mattel and Hasbro. The commercials on TV and the photos in the Sears catalog made each doll and toy look irresistible, promising hours of fun. My mother long resisted getting me a Barbie; she thought there was plenty of time for girls to be clothes-obsessed, starting at age twelve. And every Barbie outfit came with the dreaded little pieces, accessories of tiny shoes and jewelry.

When Santa finally brought me one, a blond bubble-hair doll with a wasp waist and deformed feet, arched so high that the Barbie mules did fall off and get lost immediately, a girl about my age moved in across the street (only to move away a few months later). She also loved to “play Barbies,” which did indeed involve nothing other than making up reasons why our Barbies needed to change clothes every few minutes. I eventually acquired a Ken, who was boring, and a cardboard Barbie House, that my hung-over, fumbling, grumbling dad put together for me on Christmas morning. I never got the pink Barbie convertible the girl across the street had that I was consumed with desire for and would have pilfered if given the chance. Then I would have something to confess.

I never got the cotton candy machine or the snow cone maker I begged Santa for, in letters and in person, year after year. I did get the much-lusted after E-Z Bake Oven, but after I had used up the two boxes of cake mix and the one box of brownie mix that came with it (cakes and brownies that came out medium rare), I had nothing left to bake with. It never occurred to me that I could just use part of a box of grocery store cake mix. I thought because I had a miniature oven, I needed miniature boxes of mix.

Board games seem to have been thoughtfully distributed among my friends. Judy Lindberg had Operation, which my mother refused to buy, certain I would immediately lose the pieces. To prove her wrong, I actually managed to hold on to all of the components of Mouse Trap, which was much more fun, for years. I also had Lie Detector, where you had to determine the guilty party among twenty or so suspects. I played this over and over until I learned to figure out who dun it within three guesses, which happened about the same time the batteries died, and since we never had batteries in the house, that was the end of that game. Nancy Green had Mystery Date and Careers, which let us pretend we were teenagers or adults. Those games taught me to judge boys based on their looks and that secretary was a good job. My one Congdon school pal, Nancy Erman, had The Game of Life, which I adored. So much better than slow, stodgy, unwinnable Monopoly, with useless Water Works and endless passings of Go. Life had the little cars which you filled up with your peg husband and children. Then there was the heartbreaking decision you had to make, almost at the beginning of the game, to go to college or to start working and making money. We should have figured out then that The Game of Life was rigged.

My deal with Nancy was that we would have one game of Life and then play trolls. She had at least a dozen troll dolls, in various sizes: homely, grinning, sexless, squat figures with long, neon-colored hair. I only had a few, as I had to buy mine with my own money. My mother, the toy tsar, refused to pay for anything so ugly.

When I was seven I set my heart on a Chatty Cathy, the star of seemingly every pre-Christmas toy commercials. Chatty Cathy was the most marvelous doll ever. She talked! You had to pull a string on the back of her neck to make her speak, and then she only said about five things. I was desperate for her. On Christmas morning Chatty Cathy was perched under the tree, reinforcing my belief in Santa Claus despite Nancy Green’s best efforts.

That was the year that we took an odd vacation to St. Petersburg, Florida, with the Lindburgs. Our family drove down, they flew; a week later they drove back in our car and we flew home. I have no idea whether it was to save money or see the country. I only have two memories of the car trip down: driving past an ancient kerchiefed black woman sweeping a dirt yard with a broom made of sticks, and my dad, pushed beyond human endurance by hearing “My name is Chatty Cathy” for the eight thousandth time, flinging my new doll out the car window somewhere in Alabama.

North Country Girl: Chapter 5 — Congdon Elementary

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir. The Post will publish a new segment each week.

Congdon was a big red brick pile built in 1929 and unchanged since. My second grade class still had wooden desks with ornate cast iron sides, holes in the upper right hand corner for inkwells, and decades of names scratched into the surface, even though making yet another mark on your desk was a major sin, practiced exclusively by boys. Heating vents honey-combed the building, just big enough for a child to crawl through. Everyone knew of a former student who had traveled the vents from the basement to the second floor. As the smallest kid in my class, I was egged on by my peers to repeat this journey; I bravely crept in about three feet before scurrying back out to the light.

The school had a huge gym, which was transformed into a performance space for Congdon’s annual Christmas Concert, where students sang “Silent Night” and “Up on the Rooftop” and a hundred other carols while standing around a twenty-foot Christmas tree, surrounded by concentric circles of parents perched on ancient and shaky folding chairs. We practiced for weeks for this concert. The handful of Jewish kids were left on their own for hours on end in their classrooms, to read or draw or twiddle their thumbs.

One side of the gym was a high, deep stage; it was expressly forbidden to jump on the stage and hide behind the red velvet curtains. I only saw the stage used once, when we were trotted down to the gym for a slide show of some woman’s trip to Korea, Thailand, and Cambodia. What a wonder! Someone from Duluth had actually gone to Asia! (A few years later, my paternal grandparents went to Hong Kong; my grandmother smuggled back an entire custom-made wardrobe by wearing all her new suits and dresses and coats on top of each other.)

The gym was a place of dread for me. I hated every gym class, including square dancing (which seems to have been a mandatory part of PE at all elementary schools in the country then), but apparatus day set me quaking in fear. When not in use, the “apparatus” was hung about the walls of the gym like instruments of torture. The rings weren’t so bad, I could hang by my knees forever, enjoying the rush of blood to my head, until I was kicked off by the next kid in line. But there were also climbing bars, which required chin-ups at the top, the ropes (how could it have been thought okay to send kids ten feet up in the air clinging to a rope so splintery it would have been rejected by the most horny-handed sailor, below only a mouldering two-inch-thick gym mat held together with duct tape to soften the fall?), and worst of all, the horse. My version of a vault was to run up to the horse, come to a dead stop, then heave myself over, struggling to land on my feet instead of my head.

All of our gym activities were overseen by our classroom teachers, who were uniformly unmarried, over fifty, and in varying degrees of unfitness, the worst being Miss Johnson, my fifth grade teacher, who was Mrs. Sprat fat. Our principal, Miss Brown, was of the same graying spinster ilk. The only masculine figure at Congdon was Mr. Swan, the janitor, who took the gym apparatus up and down, flooded and swept the Congdon ice rink in winter, and who could usually be found smoking a vile cigar down in the boiler room, poking at the roaring coal-burning furnace. Any classroom accident or breakage required someone to go down to that dungeon and bring back Mr. Swan with his mop and bucket. I always tried to hide beneath my raised desktop rather than have to face that scary man in his den. For any other errand, when a teacher asked for a volunteer, my hand shot up first.

A school telephone system had once been in place, as there were rudimentary black Bakelite and brass phones on the classroom wall, but they had long ceased to function, so students were sent as messengers back and forth, a wonderful chance to dawdle in the deserted halls, take a long gulp of cold water from the fountain, and hang around the principal’s office in hopes of seeing some bad boy brought in by the scruff of his neck to face Miss Brown.

Supply Monitor was the most prestigious and sought-after job, responsible for fetching chalk or construction paper each morning from the school’s supply room. I was often awarded this plum position; I was well-behaved, quiet, and a model student, which did not win me any friends.

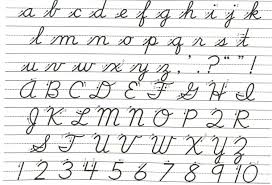

I sailed through second grade, except for two subjects. We were now expected to stop printing in pencil and learn cursive writing, including the weird capitals S, Q, and G that bore no resemblance to their print counterparts. All of the letters in a word were supposed to flow from the pen, all connected smoothly at the bottom, with the top of lower-case letters exactly touching the dotted line bisecting each row. Not only did this require a level of manual dexterity I would never have, we also had to write with a fountain pen. Each student was given a brightly colored plastic pen, perfect to chew on, and a small supply of cylindrical ink cartridges. I was unable to insert the cartridge in the pen without exploding blue ink everywhere. My mother would shake her head at my stained dresses and my unvarying “C” in penmanship, which would probably have been a D if I didn’t get A’s in everything else.

I also could not learn to tell time. Periodically during the school day we were required to look at the wall clock and write down the time. After weeks of failing to identify 10:30 or 1:45, it was discovered that I couldn’t see the hands of the clock. I was now the youngest, smallest, and only second grader with glasses. From the meager selection of children’s glasses at the eye doctor, I had picked out pale blue cat’s eyes, with silver sparkles at the corners to make a bad situation even worse.

I also could not learn to tell time. Periodically during the school day we were required to look at the wall clock and write down the time. After weeks of failing to identify 10:30 or 1:45, it was discovered that I couldn’t see the hands of the clock. I was now the youngest, smallest, and only second grader with glasses. From the meager selection of children’s glasses at the eye doctor, I had picked out pale blue cat’s eyes, with silver sparkles at the corners to make a bad situation even worse.

A few Congdon kids went home for lunch, most of us ate in the cafeteria at long wooden tables. Four days a week I got the “hot lunch,” which I retrieved on a tray from a small opening in the front of the cafeteria that gave way into a dimly lit kitchen ruled by mysterious lunch ladies. There was “lunch money” and “milk money,” which we had to remember to bring to school every Monday. Milk money went to buy waxy containers of milk to drink if you brought your soup and sandwich in a tin lunchbox that proclaimed your favorite TV show. This milk always tasted funny compared to our milk at home, which was delivered in glass bottles topped with paper discs labeled Springhill Dairies. Two or three times a year, there would be the miraculous appearance of cartons of chocolate milk, which we fell upon like wolves. On Fridays, to accommodate the few Catholic students who could not eat meat, lunch was always tuna noodle casserole, the noxious smell of which made me so nauseated I could barely eat my sandwich of red jelly on white bread.

Featured image: Shutterstock

North Country Girl: Chapter 4 — 411 Lakeview Avenue

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir. The Post will publish a new segment each week.

When I was 6, we moved out of the Woodland ranch into a fancier neighborhood, one with bigger, older houses and lots of trees. Our new home at 411 Lakeview Drive was a white, two-story house that looked like a child’s drawing: doors, windows, slanted green roof. Before moving in my mother remodeled the bathroom, tearing down the 50’s black and white wallpaper with cartoon-like drawings of people showering and shaving that I loved, as well as the kitchen, putting in a new-fangled garbage disposal, which terrified me — what if my hand got stuck! — and a very 60’s dropped ceiling of Styrofoam-like tiles. The week we moved in, I smuggled a bottle of Coca-Cola into the house, and put it in the freezer to get cold. When I popped it open an hour later the pop shot up all the way to the ceiling, splashing the brand new white tiles with never-to-be-removed Coke stains and sending my mother round the bend.

On one side of our Lakeview house were the McCauleys; they had built a little playhouse in their back yard for their granddaughters, who I never saw once. For some reason, the playhouse was locked, but I could gaze longingly through the windows at the tiny stove, sink, table and chairs. What wonderful grandparents to build a playhouse! I thought, resentful that my grandfather had only built a bomb shelter big enough to hold the entire population of Carlton.

On the other side of our house was a wooded lot, with a little creek that appeared magically in the spring, after the snow melted, just big enough to sail leaf boats down and get soaking wet up to the knees. In the summer there were interesting-looking mushrooms and tiny wild strawberries to collect. There were places in the lot where the trees were thick enough for me to pretend I was in a real forest, and that I was Red Riding Hood or Gretel.

The best part was the back yard, which ended in a five-foot scramble up an outcropping of granite. This was an excellent place to play pirates or princesses, with the huge Holy Rosary Cathedral looming behind standing in for a fortress or castle. On this rocky knoll grew blueberry bushes with tiny tart berries, and bushes with shiny red berries that looked tempting but were mouth-puckering inedible. The neighborhood kids called these “poison berries” and dared each other to eat them. There was one tree with low-slung branches that was excellent for climbing, that I once fell out of, landing flat on my back. I got the wind knocked out of me and then was frightened to death by Nancy Green, who watched me gasping for breath and cheerfully informed me that I had lockjaw and had to go get a shot.

I didn’t get my longed for playhouse, but my father put up a metal swing set that he didn’t bother to set deeply enough in the ground so it threatened to topple over every time we swung too high. If Lani and I got our swings in tandem we could watch the poles, front back, front back, being pulled all the way out of the grass. One winter my dad flooded the back yard to create our own ice rink, where I skated once or twice, before heading over to the big neighborhood rink, which had a warming shed with hot chocolate and Milk Duds and Sugar Babies, and kids to play Snap the Whip with, until the rink guy emerged from the shed to stop us from cracking our heads open. The final transformation of the back yard was into a kennel for two hunting dogs that slunk miserably back and forth for months before disappearing.

***

Grownups in Duluth had children and then immediately forgot about them, until they were required to all be some place, like dinner, or Sunday mass, or high school graduation. We were turned out of doors at an early age and expected to amuse ourselves. I stood in the street outside of our new house for about two minutes before being approached by a gang of grubby kids of assorted sizes asking if I wanted to play. They must have sniffed me out by my kid smell, a mélange of Cheerios, Crayolas, and new doll.

Nancy Green was the first friend I made when we moved into 411 Lakeview. She was a few years older than me, and all her clothes came from the unfortunately named Chubbettes department at The Glass Block, and she was an excellent organizer of spud, freeze tag, and all those other forgotten outside games. Immediately upon meeting me, Nancy eagerly broke the news that Santa wasn’t real and the Christmas presents under the tree came from my parents. I went weeping home to my mother who denied this calumny so vehemently and directed such hatred toward Nancy for telling me such a thing, that I ended up believing in Santa for several more years than I should have.

My mother decided a better friend for me was the older woman who lived across the street, an amateur naturalist. Her home did not have the usual manicured lawn. Her shadowy front yard was studded with massive pines, a scary miniature Black Forest I had to venture across to ring her bell. She was a stocky woman, with short dark hair and Germanic-looking walking shorts, who knew every tree and wildflower of northern Minnesota and insisted on pointing out all of them to me. After a day spent trailing her around, I would return home late in the afternoon, exhausted and dusty and dying of thirst, having trekking miles through the woods and along ice-cold brooks plashing down to Lake Superior. I don’t know if I was relieved or unhappy when the Amateur Naturalist moved away.

I much preferred exploring on my own. I would walk to the end of Lakeview Drive, cross Hawthorne Road, and trespass through an immense acreage of someone’s yard to reach Congdon Creek. Faint trails led up and down the banks of the creek; where they disappeared, I would hopscotch across the brook, usually falling in at least once. If I broke through the ice during a winter walk, I would have to head home immediately, before my two pairs of socks froze up inside my rubber boots and my feet turned blue. In the few months of balmy weather I could venture upstream as far as I liked, turning over rocks, collecting bits of birch bark and wildflowers, and watching water striders scoot across still pools.

Vermillion Road ran parallel to our street, I could get there by walking through the wooded lot beside our house and then the Hyleck’s side yard. Crime was so rare in Duluth that we never locked our house, but Mrs. Hyleck, who was a noted scold, was found clubbed to death in her basement one winter night, and her husband arrested for her murder. My mother attended every day of his trial, as it offered even more drama than her beloved As the World Turns soap opera. Mr. Hyleck was convicted of murdering his wife but always maintained he was innocent; he died in prison and in his will he asked that his ashes be scattered from a plane over the city that had so wronged him.

When I took the short cut across the wooded lot and the Hyleck’s yard, I was headed to the to the homes of two girls my age, Patty and Debbie, who lived next to each other and were best friends, and who graciously allowed me to play with them. Patty was thin and cute, Debbie was pie-faced and voracious; when I asked her what she wanted for her birthday, she said a jar of mayonnaise and a spoon, the idea of which sent me outside to throw up, which I did standing in one place. In September, I stopped playing with Debbie and Patty; good Catholic girls, they went to Holy Rosary’s parochial school. I started second grade in my new school, Congdon Park Elementary.

North Country Girl: Chapter 3 — The Charms of South Dakota

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir. The Post will publish a new segment each week.

While we spent every Sunday in with my dad’s parents, we saw my mother’s parents in Aberdeen once a year, over a long summer visit. We traveled by train, my sister and I in matching navy blue coats and white gloves, first south to Minneapolis and then switching train stations, onto another train heading west. We arrived in Aberdeen in the middle of the night; my grandpa Bill would meet the train and carry us sleeping girls to his car. When I woke up the next morning and saw the faded rose trellis wallpaper I knew I was up in the tower room of my grandparents’ Victorian house. My grandmother Nana loved babies, cats, and wallpaper: the dining room featured huge tropical leaves, like a Rousseau painting and a small downstairs bedroom had a meticulously detailed Old West landscape that encouraged daydreaming about cowboys and Indians.

Nana had a large garden plot across the street, where she grew vegetables; her huge side yard was dedicated to flowers, my Uncle Dale’s white box beehives, and my Uncle David’s pigeon coop. I was a bit frightened of those beady-eyed birds and my mother thought the pigeons were filthy and disgusting and forbid me to go near the coop, one rule that I happily obeyed.

Uncle David, a weird old bachelor, who had once been a noted small town athlete (too oddball for team sports, he was a champion ice skater, runner, and singles tennis player), lived with my grandparents. My Uncle Dale and Aunt Joan lived across the street, and produced a baby a year, to my grandmother’s delight; she adored lap babies, happy to spend hours rocking them and soothing them with an almost tuneless lullaby. I’m sure all of us cousins are disturbed by early memories of being ousted from that warm and cozy nest in favor of a smaller and cuter kid. Eventually even the youngest grandchild got dumped out of Nana’s lap, to be replaced by a cat.

Those visits to Aberdeen were my first chance to really wander and explore outside the confines of a yard, by myself or with a cousin or two trailing behind. Kids were let out of the house after breakfast, expected home at noon for “dinner,” eaten with my grandpa and uncles and any workers from their house painting business who happened to be around; and then sent off again to play until dark.

Aberdeen was a flat plains town, with a looming water tower that was visible from everywhere and marked the way back home. Unlike Duluth, a city that was all up and down hill, Aberdeen was perfect for bike riding. It was a lot hotter than Duluth and no one cared if we cousins turned the hose on each other, creating mud pits on the lawn. There was also that height of civilization, a municipal pool, just down the street, entry 50 cents. (Duluth, proud of its lakeside status and crisscrossed with rivers and creeks, scorned pools.) A short bike ride away was a playground whose main attractions were a snack bar and a rusty, creaky merry-go-round; we older cousins forced the littler ones to push us while we lay on our backs, heads hanging off the sides to better swirl our brains, until one of us was flung off or a pusher lost her grip and went tumbling under the spinning metal wheel. We had gravel from falls embedded in our knees all summer long. I was given a dime to spend at the snack bar there, where I was always torn with indecision.

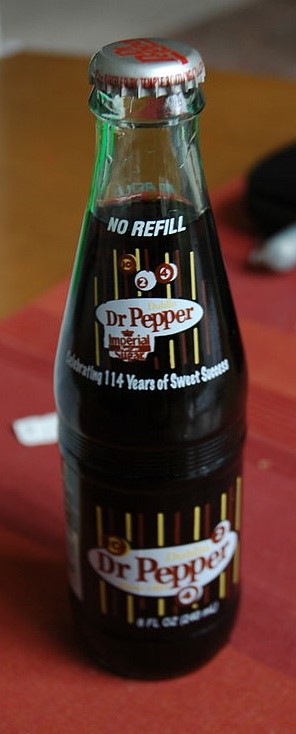

Should I get a Dr. Pepper or a pink Creamsicle (vanilla ice cream coated with raspberry sherbet)? Neither was available in Duluth, though sometimes I could find a misshapen and ice-encrusted orange Creamsicle at the bottom of a store’s ice cream freezer. The Dr. Pepper, icy cold and mysteriously delicious, came with a challenge: I had to lean into that coffin-like cooler, holding the lid up with one hand, the other navigating the bottle through a metal maze until it was finally freed at the end, without smashing my fingers. I would have to drink the entire thing right there, as the empties had to be deposited in a wire rack next to the cooler. An already melting Creamsicle I could take with me, some of the pink and white mess dropping off to sizzle on the sidewalk, some creating a sticky mess on my rubber bike handle grips.

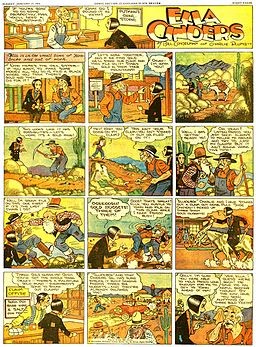

Nana kept her hair eggplant red, and wore her rouge high on her cheeks like a kewpie doll. She had to start every morning with dry toast and coffee lightened with evaporated milk. She had grown up next to her father’s cheese factory in Wisconsin inhaling the fumes from solidifying milk, and the scent of most dairy products made her sick. She was happiest hoeing in her garden or rocking a baby or collecting a new cat; the best-smelling stews on the stove were reserved “for my kitties.” My grandpa Spellman was a kind quiet man, a dead ringer for Cab Calloway, and the only adult I knew who read the funnies in the newspaper; I would hop in bed with him on Sunday mornings so we could page through the colored comics section together, admiring all of them: Ella Cinders, Steve Canyon, Beetle Bailey, Dagwood, Dondi, even Mary Worth, a soap opera in pictures.

Aberdeen had a very minor league baseball stadium, where no one in my family ever went, and a downtown lined with two-story, red brick, glass-fronted shops. On Saturday nights, we brought blankets to the park, where the adults sat around the band shell, listening to the town brass band, out of tune but spiffy in their dark blue uniforms, while the kids ran amok. Afterwards we went to Lacey’s Dairy for ice cream; I always got a cone of White House, vanilla with candied cherries and walnuts.

Another Aberdeen-only treat was my Uncle Dale’s homemade root beer, sweetened with honey from his hives. He brewed up a dark mixture with squares of root beer flavoring, yeast, tap water, and honey, poured it into glass pop bottles saved throughout the year, sealed them shut with a fascinating bottle cap press, and stored them in his basement to ferment. We kids were always warned not to open the bottles until Uncle Dale said. I could never wait that long—certainly the root beer had to be ready by now!—and at least once a summer I snuck down to the basement with a bottle opener, took a mouthful of warm, sweet, flat liquid, poured the rest down the sink, and sneakily hid the empty bottle.

North Country Girl: Chapter 2 — What I Didn’t Learn in Kindergarten

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir. The Post will publish a new segment each week.

I had started kindergarten age four on the army base in Hawaii. My father, a captain, had wrangled this early admission to get me out of my mother’s hair while she coped with a new baby. After a several month gap in my education while we lived with my grandparents, I was sent off to Cobb Elementary School as soon as we moved into the Woodland house, in the middle of the school year. I was the new kid, the smallest kid, and a year younger than most of my classmates. The old maid teacher (the Duluth Board of Education required that all elementary teachers be grey or white haired spinsters) carefully instructed me that if I had to throw up I should not run around the room but stay in one place, the only useful thing I learned in kindergarten. I painted at the easel, sang Old McDonald, pressed my hand into a disc of wet clay to create a Mother’s Day present, and made not a single friend. This would have distressed my mother if she had had the time to notice; she spent the entire day wrestling with a skinny, shrieking, thrashing toddler who fought tooth and claw against sleeping and eating and everything else.

I was friendless, but not unhappy. I had my books and my dolls and a baby sister to boss around. And every day at 3, I had The Bozo Show on our black and white TV. When Bozo wasn’t showing cartoons, but clowning around in the studio, I went back to my book while Lani rampaged through the house. Neither of us were interested in Bozo’s puerile antics or the tedium of listening to the dozens of snotty-nosed kids squashed on bleachers trying to remember their own names for the camera.

At that time we only had two TV stations in Duluth, neither of which was particularly dedicated to children’s programs. On weekday mornings there was Romper Room, which my mother attempted to park my squirming sister in front of. I was a classic Goody Two Shoes and even I was repelled by Romper Room’s “Do Be a Do-Bee” kid propaganda. And I knew that at the end of each show when Miss Mary looked through her Magic Mirror, she would never see Gay and Lani, only Billy and Nancy and Susie.

The high point of my week was Saturday morning, the one time Lani and I could spend hours sprawled in all our glory and pajamas in front of the TV. The first thing to come on screen after the weirdly fascinating test pattern were wonderful old black and white cartoons, Merrie Melodies, Betty Boop, Popeye the Sailor Man, one after the other, with no interruptions from silly clowns or idiot children. Then came Mighty Mouse to save the day. The rest of the morning was not as idyllic, consisting of old half-hour shows thought suitable for kids: Roy Rogers, featuring Trigger and Dale Evans and for some reason Nellybelle the Jeep. The Lone Ranger and Zorro, both of whom were much handsomer and more dashing than stodgy Roy Rogers. Sky King, with his cute daughter, Penny, capturing various bad guys through aviation. And my favorites, the horse shows: Fury and My Friend Flicka.

I had a few plastic toy horses, inspired by the far better collection owned by my one and only friend, Judy Lindberg, who lived a few houses down from my grandparents in Carlton. Judy and I had become friends during my parent’s house-hunting days, when she was summoned to play with me. Round-faced Judy seemed almost as friendless as I was. I envied her world-class plastic horse collection, her thousands of Legos (My mother hated anything with lots of tiny pieces), and her status as an only child, a rare exotic when two kids seemed the minimum and lots of families had five or six. Judy’s very German grandfather, Karl, and her parents, Vera, with raven Elizabeth Taylor hair, and roly-poly Julius, owned Carlton’s one and only restaurant. The small café had a few booths along one side and on the other a long counter with those glorious chrome stools; Judy and I were strictly forbidden to do any spinning on them. On the counter and tables were the most adorable china cow creamers, as Minnesotans drank coffee with every meal. I broke one once, mesmerized by the stream of milk pouring out of the cow’s mouth, and I was scared for weeks to go to Judy’s house, terrified of what Germanic punishment might be meted out by her formidable grandpa Karl.

I got to play with Judy quite often, even after our move to Duluth; my family spent almost every Sunday in Carlton. While the adults sat around drinking and talking and drinking, I walked myself down the street to Judy’s, where we played horsies or Legos or fooled around with her mother’s electric organ, or I would sneak a look at Judy’s collection of fascinating, brightly-illustrated books that tried to explain Catholic theology at an 8-year-old level. Judy complained that reading wasn’t playing, and she was right.

***

If Judy wasn’t around on our Sunday trips to Carlton, I roamed about outside by myself, or explored my grandparent’s big house. On the ground floor there was a small wood-paneled room decorated with the heads of animals. My grandfather loved to hunt; in the winter he would drive around the county, dropping bales of hay off in the woods to make sure enough deer would survive so he could shoot them the following fall. There was an elegant living room that we never sat in; everyone congregated in the new glass-walled sunroom my grandparents had added on so they could look out at the snow eight months a year. My grandmother had remodeled her kitchen at the same time; her aqua blue and pale yellow kitchen was right out of Disney’s Tomorrowland and seemed the height of modern sophistication to me: the freezer made ice, there was a dishwasher, and the Formica counters were festooned with space age parabolas.

Upstairs were “the boys’ rooms” that had belonged to my dad and his two brothers. There the main attractions were the leather albums of coins and stamps from Rhodesia, Ceylon, French Guinea, and other exotic-sounding places I longed to visit even though those countries were just a colorful bit of paper or a coin with a hole stamped out; I could not have found them on a map.

Also upstairs was my grandma’s big bedroom, neat as a pin, reeking of Youth Dew, and too intimidating for me to do anything besides look at myself in her three-sided dresser mirror.

Best of all, my grandparents had a room just for books. It wasn’t big, but it was definitely a library, with towering bookcases on all sides holding hundreds of books in no particular order. There were tomes on dentistry, dusty fabric-covered novels with tiny type and no conversations, ancient nature books with pastel drawings of birds and moths—I just had to keep pulling books down from the shelves until I found something I could enjoy. When I did, I left that book on a lower shelf so I could find it again the following Sunday. There were two books I read again and again; a book on space travel, with lurid sci-fi paintings of the rings of Saturn as seen from the surface of that planet, and sunset on Mars with its two moons hanging in the sky; and a guide to hunting in Africa, bound in leopard-print paper and filled with black and white photos of living and just-shot gnus, zebras, lions, and a wide variety of antelope. If I ever go to Africa, I will carefully shake out my shoes every morning, having seen a photo of a large scorpion that had been extracted from the author’s boot. When I was in junior high, I discovered in my grandparents’ library an unaccountable paperback of Hell’s Angels by Hunter S. Thompson, with such horrifying descriptions of sex and violence, including bikers pulling a train on one poor girl, that I took special care in secreting it behind the encyclopedias so I could read it again and again. I have no idea who would have brought that book into that house.

My grandfather had a small bedroom tucked beneath the stairs, where he retreated immediately after Sunday dinner. I thought it was funny that my grandpa’s bedtime was 7:30 until I realized years later that this was his regular time to pass out from drinking 7&7’s all day. Every Sunday I scarfed down my own dinner as fast as possible to catch Lassie and the Walt Disney Show, which later became the even more unmissable Wonderful World of Color. My mother and grandmother cleaned up the dinner plates, my dad built himself a last highball, and then we piled back in the car, my dad drunk and all of us seat belt-less, to drive the half hour back home, where I had to go immediately to bed.

My grandfather’s brother was married to my grandmother’s sister, but while my grandpa was the big man and my grandma the snooty matron in their town of 400 souls, my great uncle Cliff and great aunt Marge were stuck on a farm with a thousand turkeys. Every Christmas Eve Cliff and Marge opened their rambling 1920’s house to dozens of relatives. Aunt Marge started baking in the beginning of December: there were cut-out sugar cookies shaped like stars, bells, and camels, dusted with red and green sugars; spritz cookies, ridged wreathes of pale green, decorated with those adorable little silver balls that you’re not suppose to eat, but that I could never resist crunching between my teeth; pfefferneuse, snowy with powdered sugar, that I always forgot I didn’t like until I had popped one in my mouth; chocolate drops, that I did like, tart lemon bars, homemade white bread to be slathered with butter, and stolen, studded with candied cherries and iced with white sugar frosting.

Marge made candy as well, a feat I have tried again and again to duplicate and consistently failed at: chocolate walnut fudge and penuche and divinity. These were the main attractions for me and it was torture to gaze upon the kitchen table groaning with sweets and not be able to have any until I choked down a plate of wild rice with mushrooms and chicken, baked ham, mashed potatoes, string bean casserole, and ambrosia salad. There were bowls of many other things, such as beets and lima beans, that I didn’t eat, and since it was Christmas, nobody made me. It was farmhouse cooking at its most gargantuan. I don’t think anyone even thought of bringing a dish to Aunt Marge’s Christmas Eve. It would have been like showing up at the miracle of the loaves and fishes with a Tupperware container of pasta salad. Our family did presents Christmas morning, after Santa came. Cliff and Marge did presents Christmas Eve, between bouts of eating. There was always one present for me, so I would have something to open; I tried not to look disappointed at the handmade monkey sock puppet or yoyo doll. Then there was that annus horribilius when my sister got a Raggedy Ann doll, something I had always wanted; I gleefully torn open my own gift to reveal the dreaded stitched grin of Raggedy Andy. I cried all the way home.

North Country Girl: Chapter 1 — Duluth

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir. The Post will publish a new segment each week.

In Duluth, a tiny dot on the western tip of that great lake Superior, where I had the good fortune to grow up, each season had its own smell. Spring was definitely here when the purple and white lilacs burst forth, their pervasive old lady fragrance signaling that there would be no more snow and it was time to switch out our house’s storm windows for screens, a twice-yearly job my father dreaded. I held the ladder beneath him, trembling as the “Goddamits!” and “This is horseshits!” rained down.

Summer was the sharp green nose-tickle of new-cut grass, which I loved until I was at an age where the lawn-mowing duty fell on me. I was scared to death of the power mower and its whirling blades, as if it were some kind of wild beast that could wrench itself away and roll over my feet or go after my sisters playing on the other side of the house. In the tidy, upper middle class neighborhoods of Duluth, the lawn had to be mowed weekly to create a perfect carpet of grass. In summer, that grassy scent was always in the air, as dads who were busy playing golf during the weekend would be pushing their lawn mowers back and forth in the long summer twilight after work. A neglected yard meant something inside the house was not right.

Fall was burning leaves, which was done as often as possible purely for the joy of it. Starting in September, stolid Duluthians turned into pagans celebrating the autumn equinox. Every yard up and down Lakeview Avenue was heavily treed and leaves started falling on Labor Day, with the last ones letting go around Halloween. Great piles of dead leaves were amassed in the curbs every fall weekend and we kids would bury each other in them; that dead leaf smell was dry and papery and mingled nicely with the rich, tobacco-y smoke from the piles already burning. Raking the yard was a family project: everyone big enough to hold a rake was given one. Raking was about as permissive parenting as I ever saw growing up. If a little kid did nothing but scatter the leaves further around the yard, a bigger person would patiently follow behind and rake them up again. Once the leaves were configured into huge piles in the streets, we were allowed to jump in, strew them about, and have them cheerfully re-raked again for additional jumping. When the autumnal shadows lengthened east, the last leaves were given a final pile-up and set ablaze. The leaves vanished into smoke and it was time for dinner.

Winter was the bracing iciness of falling snow and cold, a scent that almost wasn’t one, a scent that would freeze your nose hairs together every time you inhaled. This was a wonderful smell if I were ice skating or playing broomball or tobogganing, a miserable one if I was sent out to shovel ten-foot drifts of snow from off our front sidewalk.

***

I was five, too young for yard work when we moved into our first Duluth house, in the Woodland neighborhood. It was a tiny yellow ranch, identical to the neighbors’ on either side except for color. The house was set on a small, almost treeless lot, so there were no piles of autumn leaves to jump in. The smell I remember from that house was sheep shit, which our left side neighbor slathered over his lawn as fertilizer all spring and summer.

The previous owner of our house had planted raspberry canes in the back yard, which had grown into a massive thicket that inflicted a scratch for every berry picked. Down the street was the Woodland Drug Store, with a small soda fountain along the side. My dad took our one car to work, so when I got bored of hanging around our empty yard, and started ordering my little sister Lani to search for raspberries, my mother frog marched Lani and me there for a fountain Coke, a rare treat, as my dentist father did not allow pop at home. As much as I enjoyed the cherry cokes, I loved even more twirling myself around and around on a chrome and red stool till the drug store become a blur and my head swam and my eyes crossed. That combination of sugar and dizziness was my first high.

To get to the drugstore, we had to pass by the St. James Orphanage, which looked as formidable as it sounds. I was terrified of that building and the luckless children who lived there. It was as frightening as if it were the St. James Home for Retired Ogres. Up till then, I had thought that orphans were fairy tale creatures, like elves and witches; the idea of losing not one but both parents was scary enough to send me running to the bathroom to pee the second we got to the drug store.

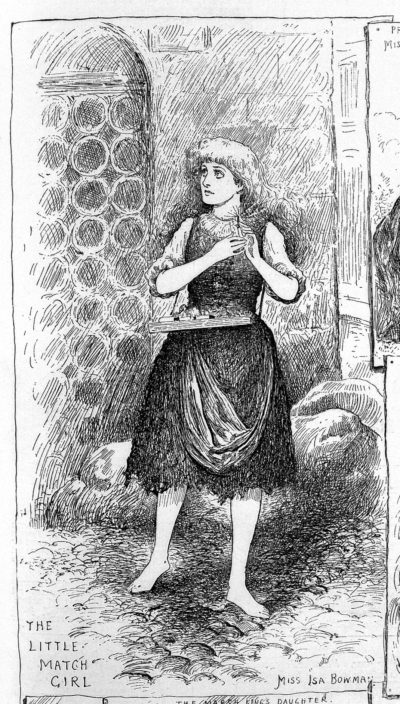

The St. James Orphanage may have inspired my conviction, every time my parents went out at night, that something dreadful would happen and I would never see them again. Or it may have been that I was a morbidly sensitive child. I had a book of Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy tales that was missing both “The Little Match Girl” and “The Little Mermaid.” The orphaned, window-peeking Match Girl watches a happy family gathered round their Christmas tree, uses her last match to try to keep warm, and then freezes to death on the street. The Little Mermaid, after months of feeling as if she were walking on knives on her new feet, bestowed by the sea witch in exchanged for her voice, sees her beloved Prince marry somebody else, dies, and is turned into a bit of foam because she doesn’t have a human soul and so cannot go to heaven. I couldn’t read either story without bursting into inconsolable sobs so my mother’s expedient solution was to tear the gloomy pages out of the book.

My sister, the feral child Lani, did not move into the Woodland house at the same time as the rest of us. She had been dispatched months before to our maternal grandparents in Aberdeen, South Dakota, while my parents looked for a place to live. Lani had been born in Hawaii, where my dad had spent two years in the army, pulling teeth out of soldiers on Schofield Barracks in Honolulu. Now we were all back in Minnesota (except for the exiled child), and he was ready to start his adult civilian life, in his own practice, and needed to find a home for his cute blonde wife and daughters.

My dad, mom, and I were camped at the other grandparents in Carlton, a town of 400 people half an hour outside of Duluth. My South Dakota grandmother, Nana, loved children, the younger the better, and had unending patience and tolerance for noise and mess. Grandma Marie, my dad’s mother, was only interested in clothes, her golf game, bridge, and daily Mass. While my dad was at work, and my mother stuck driving around with real estate agents looking at houses, I could be safely parked on the sofa with a book, or let out to explore the acres of woodland and plum orchard that surrounded my grandparents’ house. The lovely orchard would later be sacrificed by my grandfather to build a bomb shelter big enough for the entire town of Carlton to wait out a nuclear attack.

My frantic, difficult one-year-old sister was another story. An early and avid walker, she was Houdini-like in her ability to escape adult custody, and would have raced across the wide front lawn in seconds to get to the busy two-lane county road, a road that claimed a dog a year from my grandparents. Lani also cried non-stop and was an even pickier eater than I was. My grandma Marie was not about to give up mass, golf, or bridge to babysit such a creature. Lani was sent off to join the gaggle of grandchildren in Aberdeen, retrieved several months after we had moved into the Woodland house.