The Unknown World of Competitive Adult Figure Skating

The Winter Olympic Games offer a spotlight to the thrilling, high-stakes atmosphere of elite figure skating. Part performance, part athleticism, and — sometimes — part melodrama, the dazzling sport has enjoyed decades of wide appeal.

Nathan Chen’s quadruple jumps and Adam Rippon’s sassy social media presence are excellent reasons to follow Team USA this year, but Pyeongchang isn’t the only destination for competitive figure skating. Since 1995, the U.S. Figure Skating Association has held an annual national competition to find America’s best adult athletes.

These skaters often train daily, spinning and jumping on the rink and working full-time off the ice. The five classes of competitors range in age from 21 to over 66 years old, and this year they’re heading to Marlborough, Massachusetts for the championships in April.

Donna Wunder, of Yarmouth Ice Club, is the competition chair, and she thinks the resilience of adult figure skaters can be an inspiration to everyone. Although figure skating is admittedly easier on a younger body, Wunder says, “Once you have the passion to be on the ice, it’s hard to let it go.” Maybe that’s why these mature skaters have risked falls, concussions, and broken hips to dedicate hours of ice time to self-improvement. The unyielding nature of the ice rink seems dangerous, but “as a member of the older crowd, sometimes walking across the floor can be dangerous,” Wunder says.

Whether they’re seeking renewal of a former career or just beginning their new favorite sport, these grown-up skaters want the world to know that toe loops and camel spins aren’t just for the pros.

Civics on Ice

In Brewster, Massachusetts, Rebecca Hamlin grew up skating on frozen cranberry bogs while her grandfather drove the Zamboni at the famed Cape Cod Coliseum.

“I did ballet and gymnastics,and figure skating was like a combination of both. The grace of ballet with the adrenaline of gymnastics. Throw a quarter-inch blade into the mix and I was sold.”

Hamlin will be 33 at the national competition, and she’s coming back after a second-place result in 2014. “That was something I never had as a kid, having to end the career and go to school. It was a big moment,” she says.

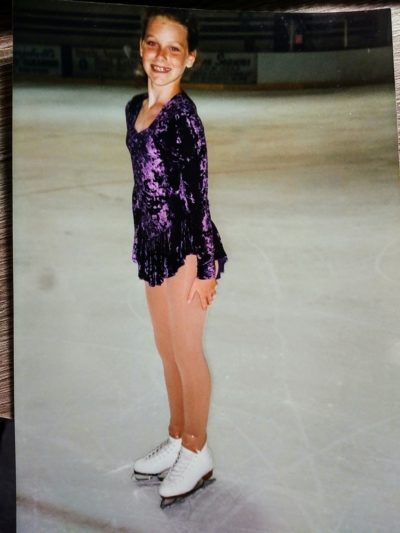

As a youth competitor, Hamlin skated at the Tony Kent Arena when Nancy Kerrigan and Paul Wylie trained there for the Olympics in the ’90s: “She was my idol. Being a 10-year-old girl in the same rink as your idol is a big deal.” It was at Tony Kent that Hamlin collided with another skater at age 11 and took a toe pick to the leg. She needed stitches, but it didn’t hold up her “fast and fearless” skating.

Off the ice, Hamlin uses her Master’s degree in International Politics as chief of staff for Massachusetts House member Timothy Whelan. While she craves the tension of a fast, packed skating program, Hamlin says running for office herself probably isn’t in the cards.

This year, she is competing with two showcase programs. After travelling with a theatre on ice team, Hamlin became interested in how storytelling and skating can combine. She will perform Annie Lennox’s “I Put a Spell on You” in a sequined black dress and Michael Jackson’s “The Way You Make Me Feel” in a beaded, hot pink one. “It’s all about how you can involve the audience in your program,” she says.

Hamlin looks at skating as a lifelong gift she’s received from her parents, who sacrificed time and money for all that goes into it. Costumes, skates, travel, and competitions add up financially, and that becomes crystal clear as an adult.

New Wave and Old Aspirations

“I don’t want to skate to Duran Duran because they’re my favorite band, and I don’t want to get sick of the music,” says Los Angeles-native Julie Gidlow. At 49 years old, Gidlow is competing in her 24th adult national competition. That makes her one of a handful of skaters to attend every year since 1995.

A self-described “rock ‘n’ roll chick,” Gidlow worked as a news editor for the music magazine Radio & Records for almost 20 years. Apart from affording her opportunities to meet INXS — and

Duran Duran — the journalism job allowed her to rekindle her love of ice skating: “It always nagged at me that I didn’t finish skating. I stopped skating, but I didn’t finish it.”

She found her passion for the ice at a birthday party at 9 years old and competed until she was 16. Gidlow grew up skating at the Santa Monica Ice Capades Chalet, the training rink of Tai Babilonia and Randy Gardner. Babilonia and Gardner were gold medalists at the 1979 World Championships, but the duo had to withdraw from the 1980 Olympics when Gardner pulled a groin muscle.

Gidlow found that, as a child, she never understood the concept of competitive skating. Her parents worked the logistics, and she just showed up. At a certain point, she didn’t feel she was skating for herself anymore. When she was a teenager, her father asked if she wanted to keep skating or to have a car, and “before he finished the question, I chose a car,” Gidlow said.

In 1994, Elaine Zayak returned to the U.S. Championships after a 10-year hiatus from competitive skating and placed fourth, receiving a standing ovation and an alternate status on the Olympic team at Lillehammer. Gidlow was inspired by Zayak’s comeback, and she

thought, if she can do that, so can I, albeit on a smaller scale. Gidlow wanted to complete her skating tests — like “free skate” and “moves in the field” — but she discovered the nascent USFSA’s adult competition and gave it a shot.

Skating to songs by Sting and 10,000 Maniacs, Gidlow fell in love with the ice all over again. She understood her parents’ sacrifices, and it gave her a new appreciation for the sport. “Everything I do is in support of my skating,” she says, “My job gets me a paycheck so that I

can pay for the things I love, and one of the things I love is skating.”

After several herniated discs, she can no longer perform double jumps or single axels, but Gidlow looks forward to the national competition each year. She particularly enjoyed the first time a fan yelled “Go, mommy!” to a skater. That was something she’d never heard before.

The Spinning Florist

Lisa Stevenson spends many weekends at the skating rink with her four hockey-playing kids, and she gets the opportunity to work on her combination jumps while she’s there. The 50-year-old mother from Nantucket didn’t grow up with a nearby rink, but she embraced figure skating in her 20s as a way to decompress.

While Stevenson was studying for her PhD in biochemistry, she found skating to be an exciting respite. In the lab, she was genetically modifying breast cancer cells, a tedious task that involved long periods of waiting. Stevenson remembered watching Dorothy Hamill skate as a young girl, so she decided to lace up some blades and head to a rink in between sessions at the lab.

After inquiring around, she got in touch with an experienced skater who could give her lessons: Konstantin Kostin, a Latvian Olympian who taught her a flip jump and a loop jump on the first lesson.

Since she had skied in high school, Stevenson had a good sense of balance, but the footwork was all new. She loves figure skating because it clears her mind and helps her to focus on learning and improving. “There’s a hint of danger. You have to get your nerve up to try something new, but once the music’s on, you kind of forget about it.” Lately, she enjoys skating to “Havana” by Camila Cabello.

Stevenson will be attending her second national competition. She notes the supportive atmosphere of the championships, saying people will throw flowers to every skater. One man makes paper flowers by hand with attached notes and gives one to each competitor. Stevenson particularly appreciates this because she is a florist herself.

Her flower company, Foxgloves and Fern, started while she was the president of the town garden club. Her house is a 1700s Williamsburg-style colonial home abutting 80 acres of conservation land, and the garden — featuring rhododendrons, indigo, anthemis, and her great-grandmother’s peonies — was designed to reflect the home’s history.

At this year’s competition, Stevenson will be performing her combination jumps and camel spins to the theme from Jurassic Park (the same music as Tonya Harding’s 1994 reskate at the Lillehammer Olympics, but Stevenson chose it because her son played it in band). She isn’t vying for a top spot, but she would like to perform her personal best. Stevenson hopes to figure skate for the rest of her life and, maybe, convince one of her kids to get into figure skates as well.