North Country Girl: Chapter 28 — The Age of Aquarius Comes to Duluth

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir. The Post will publish a new segment each week.

I didn’t tell Doug Figge about Wendi Carlson’s advice, that the key to enjoying sex is more sex. I didn’t have to. His mind was on the same track, the only track 17-year old boys’ run on, the track with the thundering locomotive of sex hurtling along, blowing all other thoughts away.

The day after the first man landed on the moon and I gave up my virginity, Doug called with the woeful news that Joe Sloan had emerged from his basement with powder burns and a singed shirt, accompanied by a powerful stink of cordite. His parents decreed that their house, including those forgotten bedrooms, was off limits.

Doug knew it was one of my mother’s class days. “Please, please,” he begged. “Let me come over. It will be okay, we’ll be quick,” he said as if that were a selling point. “Fine,” I sighed.

One of the things I learned from my first experience was that sex was messy, and should not take place on my mother’s ivory brocade French Provincial couch. Doug pulled into my driveway, I let him in the backdoor, and hurriedly escorted up him to my bedroom.

It was the middle of the afternoon and the sun streamed through my windows. I was shy about taking off my clothes in the summer glare, and not especially looking forward to seeing my fairly unattractive boyfriend naked either. I turned my back, stripped and slipped between the sheets, and there was Doug, nude and on top of me and ready.

I thought we were safe. My mother usually wasn’t home till three. But some vagary of the University of Minnesota’s college calendar or maybe the excitement of the moon landing had caused my mother’s class to be canceled that day. I heard a familiar car pull up to the house and thought “This is bad this is bad this is bad,” and tried to shove Doug off me. His eyes were squeezed shut, beads of sweat popping out on his wispy moustache; he was oblivious. “Doug Doug Doug,” I whispered hoarsely, as I heard the house door open and not only my mother’s voice, but my sisters’ as well. I pushed him harder and finally got him off me and he realized that my mother was home.

As Doug’s Corvair was in the driveway, my mother knew we were in the house alone, which she had strictly forbidden fearing exactly what had come to pass. Before Doug and I had a chance to find even our underwear, my mother flung open my bedroom door and lost her mind. She didn’t know whom to hit first. She whacked Doug about the head a few times, as he tried to find his jeans, the hell with his briefs, then she turned on me, as wordless as a banshee, unable to articulate what she had seen with her own eyes: her fifteen-year-old daughter having sex. I burst into tears and Doug made his escape.

That event is burned into my memory with almost a physical pain. I can feel the warm air coming in through the windows, pushing the sheer white curtains into the room. I can hear the torrent of my mother’s shrieks, and my entire body burning and blushing and trying to vanish into thin air. Out of the corner of my eye, while trying to duck my mother’s roundhouses, I see a blur that is Doug, holding his shirt and shoes, rushing down the stairs and out of my life.

A sadder but wiser fairy had come to undo one of my wishes, a wish that had gone horribly wrong. I no longer had a boyfriend. My mother forbade me to see Doug Figge ever again.

When I told Wendi Carlson about that shameful, sordid experience, she burst into peals of laughter, which shocked me into learning an important lesson: if your good friend cracks up at your sad story, it’s not the tragedy you think it is.

Egged on by Wendi, I held my gang of girlfriends spellbound for the remaining weeks of summer with the gripping tale of my mother catching me in bed with Doug Figge. “Tell it again!” they’d squeal, as we sat by a bonfire or dangled our legs in the water off a lakeside dock. I’d get to the point where Doug tore bare butt down the staircase, and they’d roar, squirting beer through their noses. Every time I re-told that tale of horror, it became less real, more like something that happened to another person.

“You need a new boyfriend!” cried Nancy, Wendi, and all the other girls. I wasn’t sure that I did. My romantic history consisted of a single date with Wesley Baggot, being publicly dumped by Steve LaFlamme, a forced make out session with a candidate for a skin graft, and having a boyfriend for six months that I didn’t really like and who never took me out once on a real date.

If I was going to have another boyfriend, I was going to pick him out myself. No more waiting passively for some boy to choose me; I had enough of that during those nightmarish ballroom dance classes. From now on, every day was going to be Sadie Hawkins Day.

I rejected all the efforts my pals made to fix me up. I studied the eligible guys in the packs that hovered around us, looking in vain for potential boyfriend material, someone who was good-looking and smart and funny. My imaginary future boyfriend had to go to East High, so he could hold my hand in the halls and take me to a school dance. I was through with boys who went to weird other schools, unless Joe Sloan reappeared.

Maybe it was this gritty new determination, maybe it was getting rid of my virginity at fifteen-and-a-half: I grew a backbone. I found I could talk, and laugh, and flirt with boys, ignoring the voice in my head that told me I sounded like an idiot.

Now I needed to shed my gawky nerd look, my face hidden behind those oversized tortoise-shell spectacles with the Coke bottle lenses. My mother was still not talking to me, just shooting me looks that alternated between disappointment and disgust. I turned on my father at every occasion, begging for contact lenses. Dad preferred that I remained unattractive; he didn’t know that the worst had already happened. My eye doctor won the argument for me, pointing out to my father that contacts would slow down my eyes’ deterioration to Mr. Magoo-level near-sightedness, and eliminate the need to buy new and thicker glasses every year. I got my contacts and I promptly lost one in our gold shag carpet. So much for my dad saving money on my eye care; it was back to the doctor to order another $30 contact. Now both my parents were mad at me.

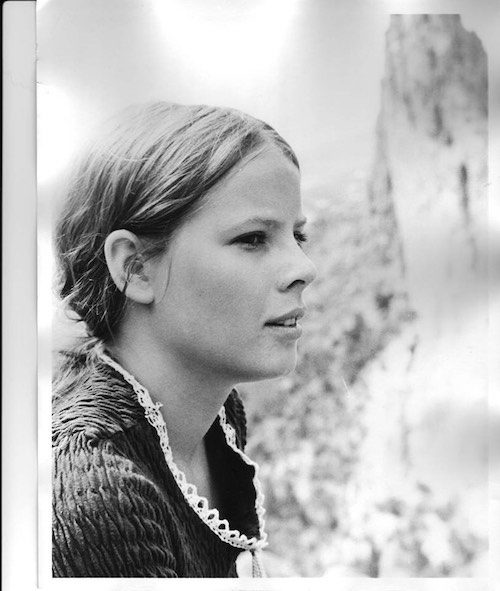

Who cared about parents when there was a potential boyfriend somewhere out there, a boyfriend who could now gaze directly into my green eyes, while stroking my hair. I hadn’t allowed a scissor to come near my head for months and my hair now flowed halfway down my back, an unremarkable brown, but thick and shiny with youth and health, perfect hippie girl hair. I also decided to stop letting my mother pick out my clothes. During our annual shopping trip to Minneapolis I ditched my mom and sisters in Dayton’s Back to School section and found an incense-smoky store where I bought a purple leather fringed jacket, a collection of gauzy Indian shirts, and embroidered bell bottom jeans. Suddenly instead of a four-eyed geek with a bad haircut, there was a cute girl in the mirror. My third wish, a wish so improbable and so desperate that I had never consciously acknowledged it, had been granted.

***

Late in August Walter Cronkite reported that thousands upon thousands of hippies had descended on a farm in upstate New York for a three-day music festival. The six o’clock news never showed any of the music, only the miles of traffic and abandoned cars and then finally half-naked people rolling about in the mud, Walter tut-tutting away like a maiden aunt. It looked amazing, the most fun a teenager could have. I watched desolate, knowing my tribe was out there, listening to the music I loved, taking the drugs I wanted. As always, life was happening somewhere else.

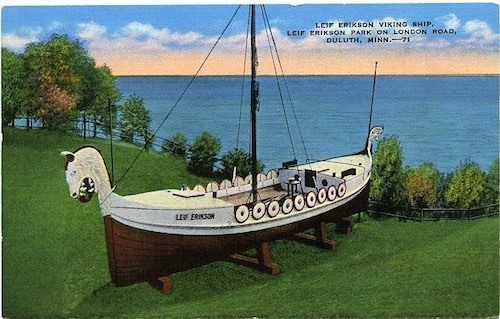

But Woodstock unlocked something in the teenagers of Duluth. As if summoned by the Pied Piper, throngs of kids coalesced in scraggy bands on the rolling green lawns of Leif Erickson Park, boys strumming guitars and girls twirling their long gypsy skirts around and around. At the downtown Woolworth’s next to the turtle tank I found a rack of buttons with peace symbols and “Make Love Not War” that I pinned on the lapel of my fringed jacket. The Age of Aquarius had reached Duluth.

On the first day of school, I walked down the East High hall into a different world. A whole subset of druggies and hippies had sprung up like dandelions. There were dozens of kids in tie-dye, patchouli oil was used way too liberally, and almost every boy, including the jocks, had hair that brushed the collars of their shirts.

I made my way up to the third floor, to Mr. Burrows’ two-hour, buttock-killing, smart-kids-only, enthralling American History and Literature Class, an educational jewel that was more fascinating and more informative than any college course, even if it did hew to the Famous White Men model, with nods to Anne Bradstreet and Emily Dickenson. As I slipped into my usual seat next to Nancy Erman, she nudged me, nodded her head sideways, and daringly whispered “New boy. Your type.” Mr. Burrows’ thundering brow turned toward Nancy at this violation of his rule of absolute silence. She gave him a twinkling Nancy smile, and, mollified, Mr. Burrows went back to the chalkboard to write: “A true relation of such occurrences and accidents as hath hapned in Virginia. John Smith, 1608,” and we were off to the races, three hundred years of history and literature to cover in nine months.

I snuck a glance in the direction Nancy had nodded in. Sitting all alone against the back wall, lit like a Renaissance angel under the slanting autumn light that poured in through the diamond-paned windows, was a boy with long dark hair that reached his shoulders and John Lennon wire-rimmed glasses. Beneath the glasses and the hair was a cherubic face, as round and sweet as an apple, a face that wore a serious, studious expression that reminded me to turn, reluctant and hopeful, back to my own interrupted note-taking on the founding of Jamestown.

This boy was Michael Vlasdic, my first love.

He was heart-meltingly handsome, and I knew that he had to be smart to be in Mr. Burrows’ advanced class. Two hours later, when Mr. Burrows allowed questions and comments, Michael sat silent, although I did see him occasionally smile, revealing adorable dimples that would be so much fun to kiss.

Michael Vlasdic was also in my lunch period, where I clocked him sitting at the back of the raucous East cafeteria with Roger Dennison, another rare new kid, who was good-looking in a blond, high-cheeked, Slavic way despite a nose like a jagged ski run, and with my old friend Eric Olson from elementary school. Eric was now known as Needle, not for his use of intravenous drugs but for his extreme skinniness. Roger and Needle both sported nicely shaggy hair, though not as long as Michael’s.

A year ago, I would not have been able to walk within ten feet of a boy I liked without my stomach flipping over and my tongue gluing itself to the roof of my mouth. But good luck and bad experiences had given me confidence. I had shed my virginity and my goofy glasses and I had Michael Vlasdic in my sights.

The new, sophisticated me plopped down uninvited among the three boys, making sure that I was next to Michael, and finally put my mother’s advice—“Just walk up to a boy, say hi and start talking”—to the test. I smiled, asked Roger where he was from (Colorado, his father worked for the Air Force and had been transferred to Duluth’s tiny base), talked to Needle, another smarty pants, about our classes, and finally turned to Michael and said “I like your glasses.”

I watched his face and my heart gave a small thump. I thought, I know this person, I have been this person, struck dumb at the prospect of talking to the opposite sex. It was as if I could read what was going through Michael’s mind: “What does that mean? Is she making fun of me? Or should I say thank you and then say I like your shirt?” I could tell he was weighing all his options as if one wrong word could open up the cafeteria floor and send him down to Hades, while the other kids laughed and pointed at him.

It was too painful. I jumped back in and carried the conversation single-handedly (look mom!) until the bell rang to send us off to class. That was also my signal to make my move. “So Michael,” I said, “What are you doing Saturday night?” All three boys exchanged shocked, mystified looks, but there was none of the horror that I used to see on the faces of the boy I asked to dance at Cotillion.

Michael quietly admitted that he had no plans for Saturday night and then looked as if he were waiting for a stinging, “Oh I’m going to a fun party” from me.

I took a breath and said, “Do you want to go out, go do something?” A beatific smile crossed Michael’s face, revealing those adorable dimples that I could have kissed right there and then. I took this as a yes. We scribbled phone numbers in each others’ notebooks and I left feeling that little squeeze of my heart and tingling between my legs that I got listening to Robert Plant moan “The Lemon Song” or re-reading the dog-eared pages in my copies of Lolita and Candy that I hid between the mattresses.