North Country Girl: Chapter 30 — Winter Tales

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir. The Post will publish a new segment each week.

The next night, snuggled in bed with Michael, I poured out my first drug experience, trying and failing to explain what made it so awesome, how I felt like Alice falling down the rabbit hole. Michael pushed himself away from me and looked unhappy. “I thought we were going to trip together the first time.” The problem with having a sensitive boyfriend is that they have feelings, which are always getting hurt.

I told Michael I would make it up to him; I would ask Stan Lewis if I could buy mescaline off him, or find out whom he got it from. Michael perked up, his dimples re-appeared, and we went back to seeing how close we could smush our young bodies together.

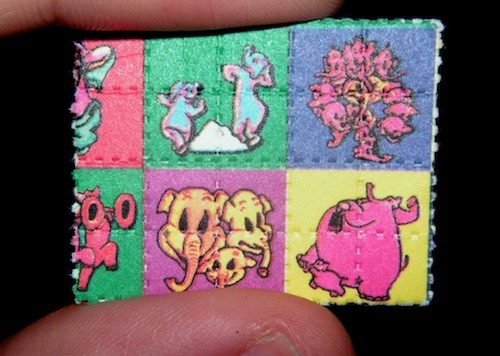

I braced Stan in the East High halls that Monday to see if he had any more mescaline. “I ate the rest of them,” he reported, then grinned like his face would crack in two. He was getting more drugs that weekend and he would count me in. Then at the London Inn I ran into Mary Ann Stuart’s old boyfriend John Bean who had blotter acid, and Wendi’s boyfriend gave her some purple haze, and everyone said there was a guy who hung out at the pool hall who had windowpane, and the floodgates were opened. Duluth had entered the psychedelic era; we were awash in drugs.

A psychic monkey wrench had been thrown into the collective brain of Duluth’s teens. Drugs were so new that drug education had not yet been invented. A parent might tentatively ask, “You don’t know anyone who takes drugs, do you?” as if there were black capsules with DRUGS printed on the side being passed around like Good n Plentys. We all soberly shook our heads no, even if we were high as a kite at the time.

Even the straightest-seeming jocks and cheerleaders were trying weed, “just to see what all the fuss was about.” Most went back to their Royal Crown Cola and Seagram’s or Grain Belt beer. But not all; at parties there would always be a couple of hulking football or hockey players huddled around the stoners, passing joints.

Mark Carroway was one of the first to go full-tilt druggie, famous for coming to school on acid every single day. Wendi Carlson sat in front of him in English and reported that when they were given pop quizzes, Mark scribbled “Mickey Mouse” illustrated with a pair of round black ears as the answer to “Who is the antagonist in Ethan Frome? What is the theme of The Scarlet Letter?” and every other question.

The going rate for a hit of acid or mescaline or whatever the seller claimed it to be was between $3 and $5. I bought that blotter acid from John Bean, using a ten-dollar bill that had arrived in a birthday card from my South Dakota Nana and then cruelly made Michael Vlasdic wait till Saturday night to trip together.

It’s probably not a good idea to give two sixteen-year-olds who already believe they are madly in love some very good LSD. If acid had been available to Romeo and Juliet, they would have said to hell with the straight world of Verona and headed off to Capri, to trip balls while splashing around the Blue Grotto.

Just like sex, that first trip sparked a hunger in both of us for more. Taking drugs became as important to Michael and me as making love. Every time we tripped we were in perfect communion. I could read Michael’s thoughts and feel what he was feeling. It was totally weird and, at the same time, exactly what I had expected to happen.

Michael and I had a limited amount of money. He had a regular weekly allowance; I got paid on those rare occasions my father happened to be around, since my mother never had any cash, relying on her charge accounts at Pletz’s Grocery and the Glass Block. I wailed, “I have to have money to chip in for gas!” My parents grasped that a broke daughter not paying her share reflected badly on them. My mother glared at my dad, who reluctantly handed over a ten or sometimes, when he wanted to play the big spender, a twenty.

A buck went to help fill the tank of the White Delight every Friday night, another went towards my share of a bottle of Boone’s Farm. The rest I spent on drugs.

If Mrs. Vlasdic selfishly planned a quiet Saturday night at home listening to Wagner, Michael and I headed out in the dazzling snow banks, down to the frozen lake, bundled up like toddlers. We’d return hours later, red-faced and ravenous, eyes whirling like pinwheels, laughing hysterically while Mrs. Vlasdic served tea and buttery pastries and chattered away in her weird accent. She had to have known what was going on.

LSD was kerosene thrown on the fire of our teenage love. Most of those wintery nights Michael was too high to walk me home, but it didn’t matter; I floated through the dark streets, with green streaks of the aurora borealis flickering above me, the world’s greatest light show. I could hear the snowflakes drifting through air so frigid it was almost liquid. I was drunk on love and tripping my brains out. I never felt the cold.

That winter was especially snowy, even for Duluth. Everyone stuck fuzzy neon orange balls on their cars’ radio antennae so something would be visible above the six-foot snow banks. One of my dad’s patients paid off his dental bill by plowing our driveway, but I was sent out every afternoon to shovel the fresh drifts off our front walk. And the snow kept falling.

Nancy Erman, an expert skier and always our leader, hatched a plan. We girls would take a bus up to Lutsen ski resort on a Friday, stay overnight, and be the first out on the trails Saturday morning. Girls who didn’t even know how to ski signed on, as this was going to be the best gang sleepover ever.

As the big Friday approached, the snow began to come down faster and thicker, until by the end of the week we were in a full-scale Minnesota blizzard. One by one, my friends’ parents put their feet down — you are not going in this weather — until Nancy, whose parents pretty much let her do anything she wanted, and I were the only ones headed to Lutsen. My mother was too intimidated by Nancy’s dad, the judge, to forbid me to go. If he thought it was okay for his daughter to travel in white-out conditions, it must be perfectly safe.

There was one snag. This whole escapade — the bus tickets, hotel, ski lift, food — ran to the astounding sum of $40. We never had that kind of money in the house, and while my dad had given me permission to go on this trip (he was a little scared of the judge himself), he had yet to produce the ready cash. He had also vanished.

And now it was late Friday afternoon and all the money I could put my hands on were the quarters we could salvage from the back of the sofa and coat pockets and a $5 bill I had put aside for drugs. No one was answering the phone at my dad’s office. There were no cell phones, no ATM’s, no way I was going. I was miserable and not just for myself: I hated letting Nancy Erman down. Being teenagers, the idea that we could just postpone the trip to the next weekend was inconceivable.

Somehow my misery touched my mother’s one last sympathetic nerve. I watched, huddled on an uncomfortable wrought iron chair, head thrown down in sorrow on the glass top table, as my mother picked up the kitchen phone and dialed one of the numbers scribbled on a pad on the wall, a number I knew by heart.

“Hello, Mrs. Erman?” My mother’s face cringed in embarrassment. I didn’t say a word. “I am so sorry, I know how much our daughters are looking forward to this ski trip. But Dr. Haubner has an emergency at his office, and, well, I somehow don’t seem to have any money, you know how that happens, can’t stay out of the shops! So…by any chance could Gay” — she gave me a pointed look, a look that meant “You owe me big time, sister” — “could you and the judge possible lend us the $40 so the girls can go skiing?” Judge and Mrs. Erman could, they handed Nancy two $20 bills, and she drove the White Delight to my house.

At least somebody — it must have been a parent, as we teenage girls were sure we were immortal — had the sense to make us take the bus from Duluth to Lutsen. I heard the familiar beep of the White Delight, grabbed my skis, and dashed out. The honking was coming from somewhere in a thick, impenetrable mist. Nancy kept honking till I found the car and we inched our way to the bus station. The White Delight was almost invisible in that blizzard; so much snow was falling that when we returned the next day, her car was covered in more than foot of powder, an unidentifiable knoll in the parking lot.

Nancy Erman and I stowed our skis in the bottom of the bus and climbed aboard. The bus was empty. The driver beckoned us in, said “Sit where you like,” levered the door closed, and we took off into the snow-filled night.

At first it was an adventure. We were the only passengers on that bus, a bus traveling blindly through the storm, the windshield wipers waging a war against the thickly swirling flakes. It was like being in a Twilight Zone episode. That thrill vanished when an hour later I looked out the window as we drove under a streetlight and recognized the Lester River bridge. “Nancy, we’re still in Duluth,” I whispered, as if it were a secret.

What should have been a two-hour trip stretched into five, but we were content, tucked together in the back of the bus, in a friendship as comfortable as old shoes. We gossiped and re-traded secrets and found new things to like about each other. The bus hummed monotonously and gently rocked back and forth as it made its stately crawl north. I was just about to say, “Remember when we used to play with those hideous troll dolls?” when I sunk into a coma, and I guess Nancy did too, coming back to life when the bus conductor shook my shoulder and said, “Lutsen. Wake up, girls.”

At the Lutsen Lodge desk a young man had managed to fall asleep standing up, his upper body splayed on the counter. We woke him and he yawned “Judge Erman’s daughter, right? He said to call him when you get here,” and handed Nancy the phone and me the key to our room. I unpacked the quart of Tango Orange Flavored Vodka and gave it pride of place on the night stand between the two single beds. When Nancy came into the room, she looked at the bottle, said “Good night Tango. Good night Gay,” and we went to bed. It was still the best sleepover ever.

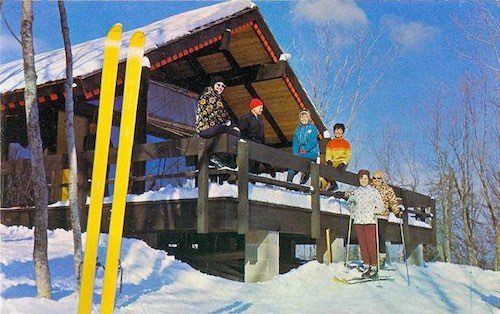

We woke to the thrill of bright sunlight, which would warm the ski slopes by a degree or two, illuminating what can only be embarrassingly described as a winter wonderland. From our window we gazed out at Lutsen’s towering ski hill, covered in the most pristine blanket of snow, a stationary chair lift etching a black line against that solid white backdrop. I heard a familiar low rumbling and a snowmobile pulled up below, driven by a figure so swaddled in layers it could have been a man or a woman or a yeti in a parka and snowpants. The boy from the desk knocked on our door and announced, “The cook just got here. Breakfast is in ten minutes.”

Nancy and I were as alone in the Lutsen Lodge dining room as we had been on the bus. We threw down our food, grabbed our skis, and crossed the silent highway to where the chairlift was shuddering into its first ascent. The only person around was another bundled-up figure who briefly held the chair lift so Nancy and I could hop in. This was a maneuver that frightened the bejesus out of me as I had more than once been pitched head first into the snow, popping off at least one ski, and forcing the operator to stop the lift, stranding people in mid-air, while someone manhandled me out of the way.

This, however, was magic time, a singularity when the world is perfect. I dropped almost gracefully into the chair lift, and we were swooping into the winter sky, a sky bluer than 10,000 lakes. I juggled the ski poles and Nancy’s mittens so she could light her first Tareyton of the day. She generously offered to split it with me; I accepted just to warm up my face, and actually held a lungful of smoke in for a second.

Then we were over the crest; we threw the safety bar back and glided away, giddy with our luck at having an untouched mountain before us. All morning it was just Nancy and me and miles of powdery snow that glittered like a carpet of crystals. We skied, we laughed, we fell into deep drifts that were softer than a pillow. For once, I didn’t insist on stopping for a mid-morning cocoa, usually my favorite part of skiing. We stayed on the slopes till our grumbling stomachs forced us into the chalet, where Nancy and I sat all alone in the Nordic A-frame, sipping delightfully scalding vegetable soup out of white china mugs. We took a remarkably quick pee, being experts at removing multiple layers of cold weather clothing, and headed back to the empty slopes.

It was a day that I have folded up and put into my mind’s pocket. Heaven could be that day. I would be happy to spend eternity in a winterscape of white and blue, silent but for the hiss of our skis and the occasional soft thump of snow plopping off a fir branch, an eternity shared with a friend who is good and true. I can see Nancy now, rosy face lit up with a smile as big as the Ritz, snow dusting her eyelashes, her long wavy brown hair loose under a knit ski cap topped with a pompom. One hand is mittenless; she is holding a cigarette up to my lips.