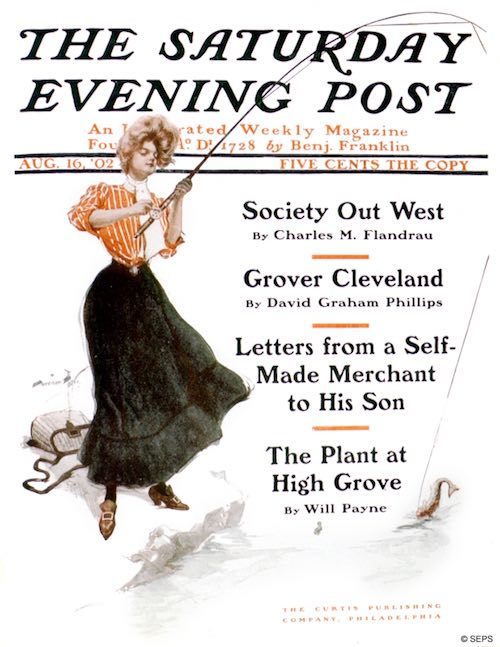

Cover Gallery: Gone Fishin’

Harrison Fisher

August 16, 1902

Harrison Fisher (1877 –1934) was an American illustrator. Both his father and his grandfather were artists. As you might be able to tell from this cover, Fisher was considered a successor to Charles Dana Gibson, famous for his Gibson Girls.

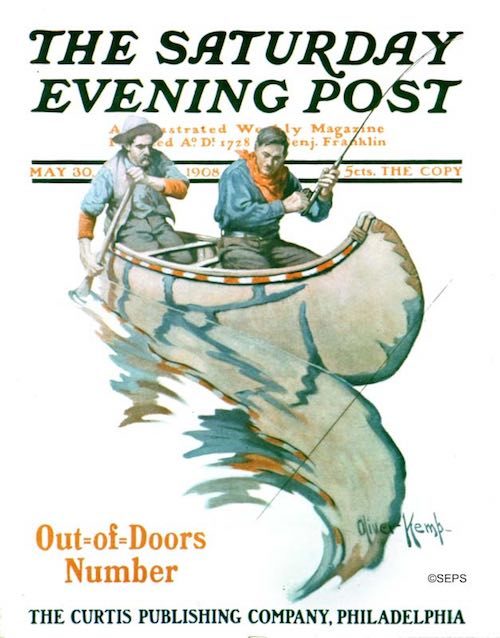

Oliver Kemp

May 30, 1908

Oliver Kemp (1887-1934) painted 11 covers for the Post. He made yearly trips to the Rocky Mountains and was fond of painting scenes of western America. His Post covers all depicted rugged men hunting, fishing, and canoeing, often with a pipe between their teeth.

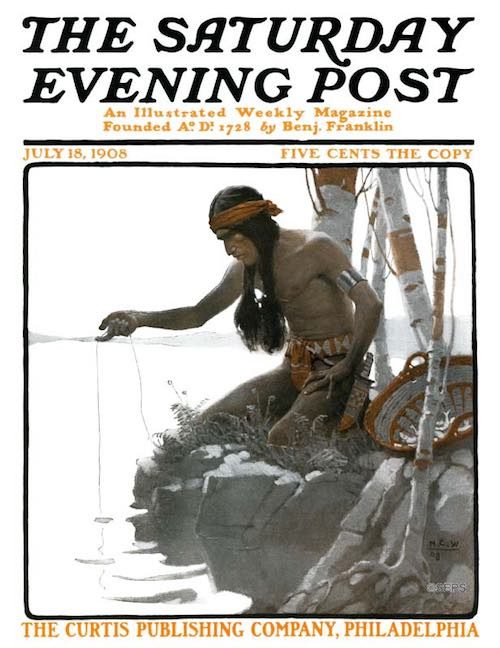

N.C. Wyeth

July 18, 1908

Newell Convers Wyeth (1882 –1945), was probably best known for his illustrations of Scribner’s classics, particularly Treasure Island. He spent part of his twenties out West, learning about cowboy and Native American culture. Wyeth painted his first cover for the Post when he was only 20; he was 25 when he completed “Indian Fishing.” N.C. Wyeth is the father of painter Andrew Wyeth.

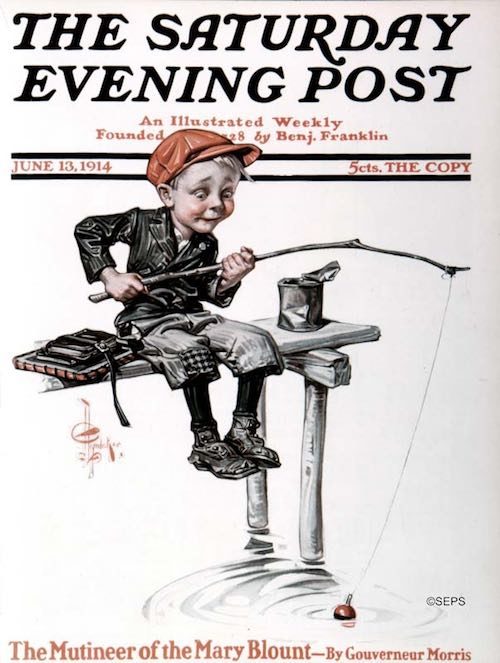

J.C. Leyendecker

June 13, 1914

J.C. Leyendecker was the most prolific cover illustrator for the Post, painting 323 covers. (Rockwell stopped at 322 out of respect for Leyendecker.) It was Leyendecker who popularized the images of a fat, jolly Santa and the New Year’s baby. While Leyendecker’s depictions of men were usually handsome and strapping, many of his children appeared emaciated and sickly, and often had bodies that were disproportionately smaller than their heads.

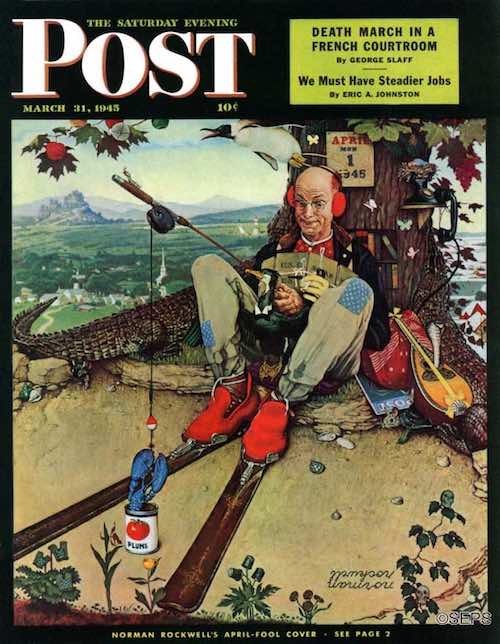

Norman Rockwell

March 31, 1945

[From the editors of the March 31, 1945 issue] Probably no Post cover has ever been more popular than Norman Rockwell’s first April Fool cover. In this week’s cover, Mr. Rockwell is trying to fool you again, and he probably will succeed. Watch out for the blue lobster. As a matter of fact, we don’t think this one is quite fair, and we’re going to tell you that there is such a thing as a blue lobster. According to Charles Mohr, of the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia, the blue lobster is a rarity, but every once in a while one of them turns up in Maine waters, and it is completely blue. John Atherton, whose covers are well known to Post readers and who is a neighbor of Mr. Rockwell’s in Arlington, Vermont, once made a peculiar face while he was talking to Mr. Rockwell, and Norman remembered it and used Mr. Atherton with this particular expression as a model for this cover. There are at least fifty mistakes. See how many you can find and compare your findings with those listed on page 80.

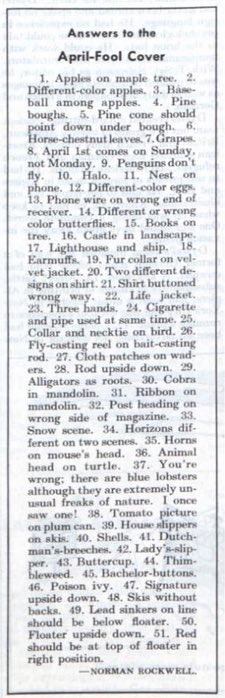

John Falter

August 13, 1949

[From the editors of the March 31, 1949 issue] On the long fishing pier at Santa Monica, California, tourists from all over the United States stand packed together like sardines while they try to catch fish. They are so grimly intent on their work or play or whatever it is that when a baited minnow smacks the water in all that silence, it makes quite a startling splash. Many of the fishermen go through their routine calmly and expertly; occasionally a greenhorn flies into a tizzy, yelps for the landing net and hauls in a dwarf flounder or something else depressing. The kids have a swell time fussing with starfish or reading a wet comic page which was wrapped around a wad of bait. Artist John Falter was non-committal about whether he caught anything—besides a Post cover.

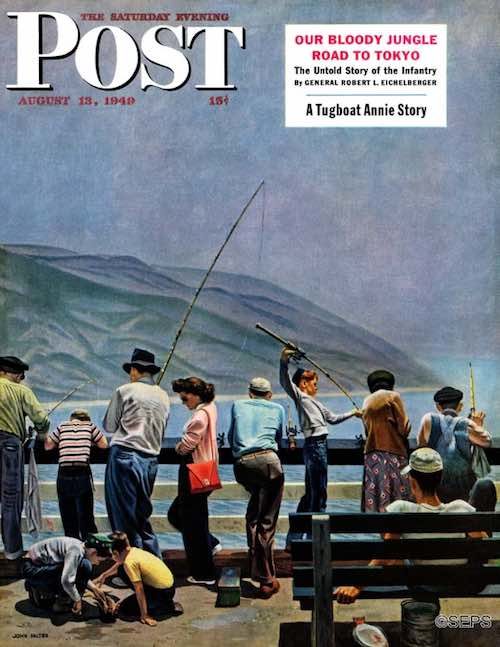

Mead Schaeffer

May 19, 1951

[From the editors of the May 19, 1951 issue] Those flies driving the man and the fish crazy are a variety known to fishermen as Green Drake. We don’t know what the fish call them. Just before this picture was painted, the man was calmly trying to feed the trout another variety of fly and they were calmly ignoring his hospitality. Suddenly, a countless family of Green Drake “nymphs,” which previously had risen to the surface of the water to hatch, discovered that they had wings, and decided to zoom into the wild blue yonder. Mead Schaeffer’s angler is trying to affix an artificial Green Drake to his line before the trout are so full of real Drakes that they sink to the bottom for a nap. Fishermen who experience such crises say that the general confusion is hard to imagine.

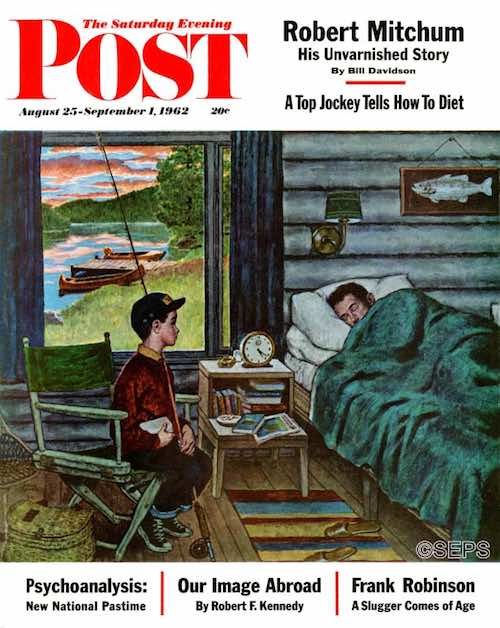

August 25, 1962

Amos Sewell

[From the editors of the August 25, 1962 issue] Forty more minutes to go, broods Amos Sewell’s thwarted young angler, and then Dad will waste still more time washing up and eating and dawdling over his coffee. From the look of this somnolent scene, it is clear that no fish will be disturbed until at least seven o’clock, and then, as any youngster knows, the fish will be settling for a siesta. Why, wonders the young sprat, can’t fathers coordinate their sleeping habits with those of fish?