1908: The Olympics Get Political. And Commercial.

Amid the celebration of the 30th Olympiad, it’s worthwhile recalling the 1908 London Olympics, and and how it changed the international games.

The Fourth Olympiad was the first truly international Olympic games held outside of Greece. It was the first Olympics to include winter events and women’s gymnastics. It introduced the rule that prohibited individual competitors; only members of national teams were allowed to participate.

And it was at the London Olympics that international squabble first began to intrude.

The feuding began at the opening ceremony, when the British Olympic committee failed to fly a U.S. flag over the stadium. The American athletes saw this and were furious. When the U.S. flag bearer marched past King Edward and the royal family, he refused to dip his flag in salute.

The British officials responded to this insult with a gesture intended to “restore the importance of the monarchy.” They changed the route of the marathon so that it would begin at Windsor Castle, directly beneath the windows of the Royal Nursery, and end at the royal box where the King awaited the winner. The fact that the new route added another 195 meters to the race didn’t seem important. (In fact, this precedent caused the Olympic committee to change the 25-mile marathon to a 26-mile event.)

Soon the complaining and protests began. After the Americans lost to England in the tug-of-war, they protested that the British team’s shoes were illegal. The United States also protested the pole-vault regulations, the official medal count, and the set-up of the 800-meter and the 1,500-meter race. And American runners were outraged when the British disqualified the American winner of the 400-meter race for foul play.

Fans from the United States added to the situation: Throughout the games, they displayed what the British felt was raucous, partisan cheering and generally poor sportsmanship. It was particularly noticeable at the finish of the marathon, as the Post reported:

When the Italian had fallen and Hayes, the American, had won, several more Americans came in, pretty fresh, then some runners of other nationalities, and, finally, an Englishman arrived.

The Americans were very sore over the treatment they had received, they had heard nothing for days but boasts that an Englishman could win the Marathon, and when the English runner finally did appear, way back in the nick, an immense American, leaning far out of his box, bellowed through a megaphone:

“Welcome to our fair city!”

The marathon is a story in itself. The leader was Italian Dorando Pietri who entered the stadium within sight of the finish line, but collapsed repeatedly. Two British officials stepped forward and ‘helped’ Pietri across the finish line. It might not have been an intentional effort to prevent the American Johnny Hayes from winning, but the American team didn’t see it that way. The Irish-American Athletic Club protested vehemently. Pietri was disqualified. Hayes won the gold.

The American team complained so often about biased British judges that the International Olympic Committee made a ruling—another first!—that future games would use judges from several different countries in future games.

Today it’s surprising to read of the intense, often bitter rivalry between Britain and America. But in the early 1900s, America’s sudden emergence as a colonial power in the Pacific challenged Great Britain’s global dominance.

Americans were still considered by many (including the future King George V) as rude and overbearing. Many in England didn’t like the American women who were marrying English lords for their titles. And Americans didn’t like the $220 million of U.S. wealth that accompanied these brides to England to shore up their noble husband’s estates.

Many Americans felt it was patriotic to dislike the British, even 120 years after the Revolution. Irish-Americans, who made up a sizeable portion of our immigrants, had more recent grievances with the United Kingdom. And now that the United States saw a possibility of becoming a global power, it needed to show it was the equal of England, and would tolerate no hint of American inferiority.

So it’s not surprising to find an occasional slap at Britain in Post editorials, like “The Desire to Win” from 1905. The editors said Britain’s sportsmanship, like its military, had become decadent because it was no longer interested in “excelling in all things, small as well as great.”

Then, shortly before the London Olympics, the English Olympic committee announced it would closely examine the qualifications of American athletes to ensure they were truly amateurs. The Post’s editors responded with a blistering editorial:

This is a proper and timely advertisement of a promise to do full duty. We hope [it indicates] the committee’s courageous intentions regarding entries from its own country.

Certainly American sportsmen trust the English committee will give its home athletes a more thorough inspection, as to their ethical qualifications, than has been the case in any previous competition of an international character.

Some Americans have taken this announcement of the English committee as a bit of mud-slinging, but, if so intended, as I doubt, it may be overlooked as another Swettenhamism.*

*This refers to a recent dispute in Jamaica. When a hurricane struck the island, the admiral on a U.S. Navy vessel sent marines ashore to protect the property of Americans. The island’s British governor, Alexander Swettenham, issued a harsh criticism, which asked how America would like Royal marines landing in New York to protect British property. He was soon ordered to issue an apology, but Americans remained incensed for months afterward.

Americans who are familiar with the athletic conditions of the two countries will not take very seriously any covert attack by Englishmen, who are hardly in a position to indulge in the smallest character-besmirching foray.

Well-informed Britishers know, to their sorrow, the depth of their athletic degradation. Outside of the Oxford and Cambridge Universities, track athletics in England reek with professionalism and dishonesty. There is an athletic association which pretends to govern the amateur sport of Great Britain, but it has proved wholly incompetent. The bookmakers rule at track meets, and their corrupting influences upon certain (and the best, athletically speaking) grades of non-university athletes have swept over the half-hearted efforts of the governing body.

If the London Olympic committee lives up to its advertised intention, the English team will have few prominent athletes outside of those who are numbered on the university lists.

The situation is different in America, where the Amateur Athletic Union holds the lines in a firm grasp. Here track athletic laws are made comprehensive and are honestly enforced, which is more than can be said for England. We have our troubles, it is true, now and again—and man is not infallible on either side of the Atlantic.

It will be well, if for the protection of its own athletes, the American Union scans with careful eye the list of English non-university entries.

While the politicizing of the Olympics started before the events, the commercializing began when the athletes got home.

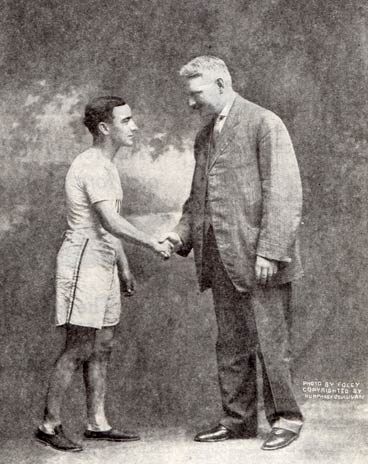

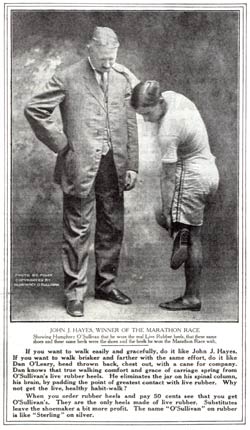

Two months after his return John Hayes gave what is probably the first endorsement of equipment for runners: the O’Sullivan Live Rubber Heels.

He is seen in these 1908 advertisements from the Post, alongside Mr. Humphrey O’Sullivan, who urged everyone—

When you order rubber heels and pay 50 cents see that you get O’Sullivan’s. They are the only heels made of live rubber. Substitutes leave the shoemaker a bit more profit.

The name “O’Sullivan” on rubber is like “Sterling” on silver.