North Country Girl: Chapter 10 — The Return of Miss Ritchie

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir. The Post will publish a new segment each week.

The August before fourth grade, when we returned from a back-to-school Minneapolis shopping trip, there was the letter from Congdon with my class assignments. “You have Miss Ritchie again for fourth grade,” reported my mother.

A miracle! In the age-old tradition of Congdon Elementary, teachers picked a grade and stuck with it. They taught the same grade in the same classroom until they retired or dropped in the harness. But I had a second year with Miss Ritchie, another year of being singled out for my excellent work and good behavior, of having my book reports and stories read aloud, my clumsy shoebox dioramas given pride of place.

Perhaps Miss Ritchie, with her seniority, had been allowed to cherry pick among the students. All the smartest kids were in her fourth grade class, and none of the unruly boys.

But the post-Sputnik changes in education finally began to creep into our 1930’s style schooling, into those sickly green painted plaster and chalk boarded school walls.

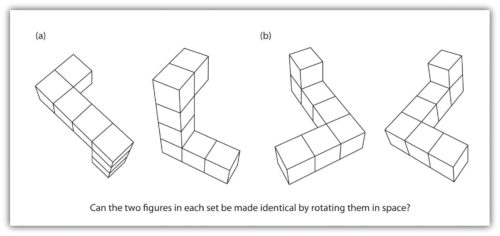

Early in the school year, we were escorted one by one into the library, where a serious young woman administered IQ tests. I was thoroughly enjoying myself until we got to the section on spatial thinking. These questions had no words or numbers; they were a series of connected squares. The multiple choice answers were four shapes: pick the one the squares would make when put together. I got the first one, which was a plain six-sided cube, after that it was pure guesswork. It felt like there were hundreds of these stupid problems, pages and pages of squares becoming more and more complicated with ever more terrifying, hundred-sided completed shapes to choose from. I was sure that this stone-faced lady thought I was an idiot.

Our fourth grade classroom boasted the latest in educational technology: a brand new SRA Reading Lab and a box of color-coded “cards” (actually four-page booklets). As the smarty-pants class, we all started a few shades up from the bottom, assigned a color based on our Iowa Reading Test scores from the year before. During “reading” or whenever I had free time, I selected a card from my assigned color. I read the little story, or more often, fairly boring non-fiction article, and then answered questions about it. This measured my reading comprehension at each level. I tore through those booklets, heading for the twinkling silver category at the top. To my disappointment when I got there, the silver cards contained the dullest readings of all. I recall slogging through a biography of Roger Bannister, the man who broke the four-minute mile, and only slightly more interesting, an article about how the movies used subliminal advertising to get people to eat more popcorn.

Math was still done out of battered textbooks, long division and decimals solved on the blackboard and on smudged blue mimeographed worksheets. Social studies and science were also taught directly from the textbooks. Miss Ritchie was still not overly fond of either subject.

Our student teacher that year specialized in music appreciation. She took us through each section of the orchestra — strings, reeds, brass, and percussion — instrument by instrument. She had it easy; most of her lessons were playing records that featured different musical instruments and trying to get us to identify them. This request was met by shrugs from the male half of the classroom, who were disappointed that the lights remained on, unlike last year’s art studies, when they could misbehave in the dark until the looming shadow of Miss Ritchie rose from her desk to end their hijinks. For her final class, the student teacher finally got around to playing real music; she played “Peter and the Wolf” and “Sorcerer’s Apprentice” for us on Congdon’s crappy, tinny record player, urging us to name the instruments in our head while we listened.

In my ongoing role as biggest geek in Congdon, I was enthralled and decided I loved classical music. The soundtrack at home was non-stop Broadway show tunes; my father was a frustrated Robert Goulet. My sister and I marched around the house singing, “The Rain in Spain” and “Seventy-Six Trombones.” I had watched Music Man and Bye-Bye Birdie on TV, but the plots of the other “Original Cast Albums” I had to figure out from the one-paragraph synopsis on the back of the record sleeve. I was stunned when I finally saw My Fair Lady that “I Could Have Danced All Night” wasn’t about Eliza’s night at the ball. One of the few Original Cast albums my father didn’t have was Gypsy, which might have been too racy for his Catholic upbringing. When NBC in a daring move ran Gypsy on Saturday Night at the Movies, my sister and I, faithful weekly viewers unless it was a Western, were spellbound. For weeks after seeing Gypsy, Lani, who weighed about 40 pounds and vanished if she turned sideways, practiced stripping down to her panties in front of our bedroom mirror, while belting out “Let Me Entertain You.” My mother was amused, but I don’t think she ever told our dad about these performances.

***

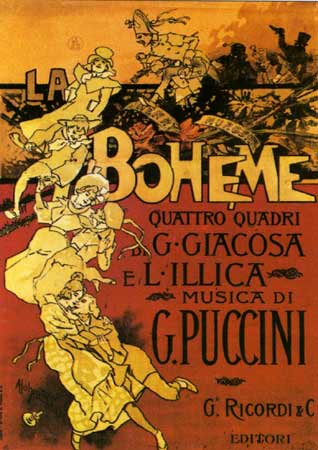

Around the same time I discovered classical music, my mother’s best friend, Karin Luster, had her brush with fame, Duluth style. In those years, the touring company of the Metropolitan Opera made it all the way up to the high northern latitudes of Duluth to do two performances in the Denfeld High School auditorium. That year it was La Bohème, and the company was in need of a local poodle for Musette. Karin volunteered her chocolate toy poodle, named, of course, Fifi. Karin longed for stardom; she was always the first and the loudest at the piano bar. She was thrilled that Fifi would be appearing on stage with the Metropolitan Opera. Karin, my mom, and I went to the Friday night performance, my first exposure to opera. When Musette swanned on stage in Act I, ready to launch into her song, there was little Fifi towed behind her on a leash, frantically scrabbling away from the stage lights, and finally showing his displeasure at being there by peeing all over the floor. The next night Musette entered sans dog.

My mother was delighted to cater to my highbrow inclinations. “I always wanted a daughter who played the harp,” she sighed. She truly believed that behind the book, behind the glasses, there lurked inside me a germ of talent for something. I took piano lessons from a grey old lady whose house smelled of lavender and cat piss. I hated sitting next to her on the bench, her sticky, wobbly skin touching my arm, the metronome ominously ticking away, and I hated practicing at home even more. I managed to forget to go to enough lessons (which had to be paid for anyway) while showing so little improvement (never advancing beyond the first John Thompson’s Modern Course for the Piano with its bright red cover and charming line illustrations) that I was finally allowed to quit.

I have vague memories of being dragged to dance lessons as a four-year-old in Hawaii with a bribe of shaved ice afterwards, and of quitting in a snit when a twelve-year-old was cast as Cinderella in the big recital, a part I thought belonged naturally to me. My mother did not give up hope that I could be taught to dance. A few years later she found yet another older, overweight spinster who once a week moved all the furniture in her living room aside and gave tap dance lessons. Again, I failed to thrive, having constant doubts about which was my right foot and which my left. The teacher believed that the solution was to stand next to me in the line of tiny dancers in black leotards, grab my upper arm in her iron claw, and shove me back and forth while howling either “Shuf-fle STEP! Shuf-fle STEP!” or “WAY down UP-on the SWAN-ee RIV-er!” I manage to soon escape that hell, although not without considerable bruising.

I was not going to be a talented wunderkind like Pamela Nishus, the pork-faced, noxious, same-age daughter of one of my mother’s friends who went to Holy Rosary, thank goodness, so I heard about her a lot more than I had to actually see her. Pamela sang, Pamela danced, Pamela was always the star of any play or recital, her proud parents beaming in the front row. Didn’t I want to go see Pammy’s show? No. Pammy could go to hell.

Despite my complete lack of talents, thanks to the student teachers who dropped down on us for a few weeks at Congdon, I became an art appreciator. I could identify the artists, name the instruments, recognize the composer. I liked going to museums and concerts; didn’t performers need audiences? (With the exception of Pamela Nishus.)