5 Classic American Pranks (and a British One)

Ever since rebellious colonists dressed as Native Americans and vandalized the beverages of the occupying British forces, we’ve been a country that loves elaborate pranks. Some pranks achieve infamy, becoming a kind of Prank Everest that other creators of shenanigans aspire to emulate. We look back at five of the greats, plus one British stand-out (because, you know, the tea).

1. The Max Headroom Intrusion (1987)

Thirty-two years ago this week, Max Headroom appeared on television in Chicago. That wasn’t a terribly unusual event in 1987, as the AI TV host character (played by Matt Frewer) had debuted two years earlier and popped up in everything from music videos to Coke commercials to an ABC TV series. This time, the appearance came via pranksters who hijacked the signals of WGN-TV and WTTW, two Chicago stations. The first intrusion, during The Nine O’Clock News on WGN, featured a person in a Max Headroom mask and lasted for 28 seconds until engineers shut it down by changing the frequency of the transmitter (which was located atop the John Hancock Building).

The signal interruption on WTTW lasted 90 seconds during an episode of Doctor Who, and included all manner of weirdness. The masked Max made reference to Chicago sportscaster Chuck Swirsky, Pepsi, and WGN’s origin as the “World’s Greatest Newspaper.” He also exposed his bottom to be spanked with a flyswatter. It took longer for the engineers to take down the signal, as no one was on duty at the (then) Sears Tower transmitting station at the time.

The intrusion made national news and remains a touchstone in the hacking community. To this day, the perpetrators remain unknown.

2. The War of the Worlds (1938)

The Saturday Evening Post has reported extensively on this one. On October 30, 1938, Orson Welles and company broadcast a radio drama based on the H.G. Wells classic The War of the Worlds. However, the storytelling technique that they used was that of a series of news broadcasts interrupting “regular” music programming so that it sounded like actual news. While reports of actual panic vary, a good chunk of listeners did believe that a Martian invasion was on. As the program reached the end, the New York Police showed up to shut the production down. Welles gave a tongue-in-cheek apology, but the legend would live on. Just two years later, Welles would begin shooting his first feature film, the classic Citizen Kane.

3. The Society for Indecency to Naked Animals (1959)

We’re sorry to report that The Post missed the boat on this one. Alan Abel, a writer and inveterate hoaxster who put together pranks on a grand scale, pitched a story to The Saturday Evening Post that was originally satire about a fictional organization with the slogan “A nude horse is a rude horse.” When the editors rejected it, Abel reworked the story into an elaborate media hoax; he sent a number of press releases out about the Society, a parody of moral panic groups that implored the public to dress and cover nude animals. Abel recruited multi-talented comedy legend Buck Henry to pretend to be G. Clifford Prout, Jr., the fictional head of the equally fictional group. The prank lasted for years, beginning with wide notice during a segment on The Today Show in May of 1959 and hitting a kind of zenith as Henry appeared in a pre-recorded interview package as Prout on The CBS Evening News in 1962. Members of CBS anchor Walter Cronkite’s staff recognized Henry, and the esteemed newsman (at the time a very steamed newsman) called Abel himself to read him the riot act. Time magazine ran a piece on the hoax in 1963, and Abel recounted its origins and spread in his 1966 book, The Great American Hoax.

4. The Great Rose Bowl Hoax (1961)

A story on The Great Rose Bowl Hoax from KRQE

A school attempting to prank the opposing team or their fans during a game is nothing new. A school that isn’t involved in the game, and yet somehow manages to prank both teams AND network television? Now that’s something else. That went down during the 1961 Rose Bowl game between the Washington Huskies and the Minnesota Golden Gophers. The California Institute of Technology is very close to the Rose Bowl, which gave a group of enterprising students (“The Fiendish Fourteen”) the prime opportunity to pull off something brilliant. Future physicist and fantasy author Lyn Hardy pretended to be a reporter and interviewed the Huskies’ head cheerleader to get information about their half-time card-flip, in which the Washington side of the stadium would hold up cards that spelled out HUSKIES. Hardy and company swiped a copy of the instruction sheet from the cheerleaders, who were staying at the Caltech dorms, and then replaced the old sheets with their reworked copies. At halftime, when the Washington cheerleaders called for the cards to be raised, the cards showed the other side of the stadium, and 30 million viewers at home, one word: CALTECH.

The effort has been called the greatest college prank of all time. It has inspired similar efforts; in 1984, Caltech students rigged the scoreboard to show Caltech beating MIT, although the game was being played by UCLA and Illinois. Yale pulled off a similar prank in 2004, tricking a Harvard student section into holding up signs that spelled out “We Suck.” The pranksters also registered harvardsucks.org and posted a behind-the-scenes video of how they made it work.

5. MIT Creates Building-Sized Tetris (2012)

The Green Building, designed by Araldo Cossutta and I. M. Pei, is an iconic structure on the campus of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. The building’s grid-like appearance invited the Holy Grail of hacks: could the building be turned into a game of Tetris? After a brief attempt in 2011, hackers installed wirelessly controlled LED lights in all the windows above the first floor that were controlled by a unit in front of the building. The effort, achieved on Campus Preview Weekend, allowed prospective students to play building-sized Tetris along with their future classmates.

Honourable Mention. Big Ben Goes Digital (1980)

From across the pond comes an April Fool’s Day classic. On April 1, 1980, the BBC broke news that iconic Big Ben was going to be converted into a digital clock. The BBC Japanese service went so far as to say that the clock hands would be sold to the first four listeners that called in with an offer. Of course, people were properly outraged. The 1980 bit has been revisited again and again over the years, with publications like The International Business Times putting their own spin on the gag.

Featured image: Max Headroom broadcast signal intrusion (Alamy).

News of the Week: Starbucks, Stamps, and How Staying In Is the New Going Out

And Now, a Scolding from the Internet

Starbucks has apologized to a customer after the man got a note on the drink he ordered at one of the chain’s Florida locations. Where the customer’s name would ordinarily be was the phrase “Diabetes Here I Come,” presumably because the man had the audacity — can you believe it? — to actually order something he wanted to order: more syrup in his Grande White Chocolate Mocha.

I’m always amazed — and maybe at this point I shouldn’t be — when people on the web have the completely wrong reaction to a story like this. You would think that most of the comments on this story would be on the customer’s side, that maybe baristas at Starbucks shouldn’t be dumping on customers via their coffee cups. But this is the world of internet comment sections, and many reactions are along the lines of “He shouldn’t be drinking that!” and “You mean to tell me he added more sugar to something with a ton of sugar already?!?”

Talk about missing the point. Or maybe they see the point very clearly and have instead decided to dump on the guy and give their flawless moral opinions, because that’s what comment sections and social media are for now.

Stamp Prices Are Going … Down?

That’s not a typo or a hallucination; stamp prices are actually going down.

Stamps have been 49 cents for the past few years, but last Sunday, the price dropped 2 cents to 47 cents. Postcard stamps — and I always forget about those — have also gone down, a penny, to 34 cents. The reason? A program that allowed the United States Postal Service to raise prices on stamps to make up for lost revenue when the volume of mail decreased during the recession has come to an end. I have no idea why the price of the stamps is going down instead of just staying the same, but I won’t argue with a discount.

It’s the first time stamp prices have gone down since 1919.

Nothing Left Unsaid

Did you know that CNN host and 60 Minutes correspondent Anderson Cooper is Gloria Vanderbilt’s son? I know, I know, that’s old news by now, but I’m sure there are some who didn’t realize it, and maybe you knew it but forgot that you knew it.

Vanderbilt is 91 now, and not only do she and Cooper have a new book out, The Rainbow Comes and Goes, but a new HBO documentary about her life, titled Nothing Left Unsaid, premiered last weekend. I caught it and it’s well worth seeing. It’s not only a fantastic look at Vanderbilt’s life, including the infamous custody trial she was involved in at an early age, her marriages and business successes, and the suicide of Cooper’s older brother Carter, it also turns out to be a rather surprising and inspirational meditation on the power of art and how to go forward in life. It’s really well done, and I recommend you take a look.

RIP Arthur Anderson

The actor started as a child actor on radio and Broadway with Orson Welles’ Mercury Theater and appeared in many movies and TV shows, including Midnight Cowboy, Zelig, and Law & Order. But you might remember him as the original voice of Lucky the Leprechaun in a series of Lucky Charms cereal commercials from 1963 to 1992:

Anderson passed away last week at the age of 93. In 2010, he released the autobiography An Actor’s Odyssey: Orson Welles to Lucky the Leprechaun.

Robert Osborne Will Be Absent from TCM Film Festival Again

Well, this is rather too bad. For the second year in a row, Turner Classic Movies host Robert Osborne will not appear at the TCM Classic Film Festival, which will take place in Hollywood from April 28 to May 1. In a letter to fans (PDF), Osborne says that a health problem will sideline him again this year. In 2015, a health problem also made Osborne miss the annual get-together. The classic political thriller All The President’s Men will open the festival, and guests this year include Carl Reiner, Elliott Gould, Eva Marie Saint, Stacy Keach, and John Singleton.

Osborne says that everything’s okay, though, and he’ll be back on TCM soon.

Going Out Tonight? Don’t Bother!

Big is the new small! Wet is the new dry! Stamp prices going down are the new going up! And going out is the new staying in.

Apparently, people aren’t going out as much as they used to. And as Molly Young points out in her interesting essay at The New York Times’ T Magazine, you can pretty much blame the internet and television.

You can do everything from the comfort of your home now. You can binge on movies and TV shows, shop, post pictures, order food, find a soul mate, and most importantly, you can hang out with friends without, well, actually hanging out with your friends. There are also many jobs you can do from home now, so you don’t even have to commute to work every day. If you carefully plan things out, you never have to leave the house again!

I’d just like to say that if staying in really has become the hip, cool thing to do, then I must be a trailblazer, because I’ve been staying in for years.

Happy Tax Day Everybody!

It’s April 15. What, you haven’t done your taxes yet? What the heck are you doing reading this then?

I did my taxes the other day, and while I would never call the process “fun,” I felt a certain amount of pride and accomplishment when I finished. Of course, writers are notoriously bad when it comes to math, so I have no idea if I even did them correctly. But hey, I did them!

If you really haven’t done your taxes yet, don’t stress out too much; you’ve got a little extra time this year. Because Friday is a legal holiday for public employees in Washington, D.C. — it’s Emancipation Day — we all get an extra weekend to procrastinate. Taxes are due on Monday, April 18, this year. But why wait? Do your taxes today so you don’t have to worry about doing them over the weekend.

Today is also National Glazed Spiral Ham Day. I don’t know if you can combine that with doing your taxes in any way, but if you do, let us know.

Upcoming Events and Anniversaries

Bay of Pigs invasion (April 17, 1961)

Here’s how The Saturday Evening Post covered the military plan and the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Benjamin Franklin dies (April 17, 1790)

Franklin did many things in his life, including starting the newspaper that eventually became The Saturday Evening Post.

The midnight ride of Paul Revere (April 18, 1775)

It really should be called the midnight ride of Paul Revere and William Dawes.

The San Francisco earthquake (April 18, 1906)

The destructive quake hit at 5:12 a.m. and killed 700 people, a number many researchers think is actually a lot lower than the actual death count.

Ernie Pyle dies (April 18, 1945)

The Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist died after being struck by a Japanese machine gunner’s bullet.

“In God We Trust” first put on U.S. coins (April 22, 1864)

Here’s a timeline of how we handle faith in America, including putting those words on our currency.

News of the Week: Words, Welles, and Why Celebrities Apologize in Advance

New Words (Merriam-Webster Division)

OMG you won’t BELIEVE what new words have been added to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary!

That line is an example of “clickbait,” those incredible, excitable, over-the-top headlines that make you click on something to find out more, and it’s one of the 1,700 new words added to the Merriam-Webster Unabridged Dictionary.

What’s odd is that most of these words are ones we would never actually use, unless we’re talking specifically about the words or in a story like this. When was the last time you were talking to your friends and used “jeggings,” “NSFW” or “WTF?” Those last two you’d probably just use the entire phrase. Some words, like “eggcorn,” are ones I’ve never even heard of before (it’s a word or phrase that you use by mistake but it sounds like the correct word or phrase, like when you don’t hear song lyrics correctly). The definition of “slendro” is “a pentatonic tuning employed for Javanese gamelans that divides the octave into five roughly similar internals.” Is there a dictionary that will translate what that sentence even means?

I hope that when you look up “emoji” in the dictionary there’s no text just little pictures.

New Words (Scrabble Division)

1,700 words? That’s nothing! Collins Official Scrabble Words has added 6,500 new words to their rulebook. One of the words is “cazh.” Try to guess what that means. We’ll get to that in a minute.

Other new words added include “blech,” “thanx,” “newb,” “bezzy,” and “yeesh.” And I’ll stop listing the new words now because language doesn’t seem to make sense anymore. The inclusion of new slang is irritating veteran Scrabble players. I would guess that most people who play the game don’t use this official guide to the words, they use a traditional dictionary and many of these words wouldn’t be in there (yet). I haven’t played Scrabble in a long time, so maybe people use the Web now for disputes?

Oh, “cazh”? It’s short for “casual.” So you’ll get to use that the next time you play Scrabble (a good word since it has a C, a Z, and an H), and your opponent will say, “That’s not a word!” and you’ll get online and prove that it is and he or she will be really upset.

Can You Use Those Words in a Sentence?

Perhaps one day the words above will be used at the Scripps National Spelling Bee. The finals were held last night on ESPN. Here are the results.

It’s interesting how a spelling bee is aired on the top sports network every year. I’m not sure how this got into the realm of sports (see also: poker). Shouldn’t they also cover events like Monopoly tournaments and chess matches too?

Lost Orson Welles Memoir Found

Someone needs to start a blog that just keeps track of “lost” or “missing” manuscripts and other items that people find years later. We’ve had a lot of them lately, from Harper Lee’s lost To Kill A Mockingbird sequel to the lost Dr. Seuss story to a lost Sherlock Holmes story that actually might not have been written by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle at all.

Now comes word that an unfinished memoir by actor/director/writer Orson Welles has been found. The pages were discovered in eight boxes that were shipped from Croatia by Oja Kodar, who was Welles’s partner when he passed away in 1985. It’s titled Confessions of a One-Man Band, and in it he talks about people like Ernest Hemingway and Rita Hayworth, and what it was like to navigate Hollywood (and why he couldn’t complete a lot of the projects he wanted to make).

This is a big year for Orson Welles fans. Besides this memoir, his unfinished last film, The Other Side of the Wind, will be completed if $2 million can be raised in a crowdfunding campaign.

Introducing the Pre-Apology

Jaguar PS / Shutterstock.com

A lot of celebrities say dumb things. Of course, a lot of people in general say dumb things, but when you’re a celebrity it’s reported by every single website in the world. Add social media to the mix and it seems like every celebrity is just 140 characters away from saying something that would seriously hurt their career. Then they argue with people on social media about it, which just makes everything worse, and that leads to the inevitable heartfelt apology, either on that same social media page or Access Hollywood or maybe Dr. Phil.

One celebrity is trying to head that off at the pass. Chris Pratt, one of the stars of Parks and Recreation and Guardians of the Galaxy, has already released an apology. It’s not for something he said or did, it’s for something he might say or do. Pratt has a post on his Facebook page where he apologizes for all of the dumb things he might say on the upcoming press tour for Jurassic World. He was probably inspired by the controversy-which-really-shouldn’t-have-been-a-controversy sparked by the interviews Robert Downey, Jr., Jeremy Renner, and Chris Evans gave several weeks ago promoting Avengers: Age of Ultron. Downey actually walked out in the middle of an interview, while Renner and Evans apologized for calling Black Widow a “slut.” At the same time, Renner released a statement apologizing for a tasteless joke about “a fictional character,” which seemed like a little dig at the people getting oh-so-upset by a sarcastic joke about someone who doesn’t really exist.

Kudos to Pratt. It’s refreshing to see a Hollywood star who not only has a sense of humor about this stuff but is actually Web-savvy too.

National Mint Julep Day

The Kentucky Derby is always held the first Saturday in May, so you would think that National Mint Julep Day would be held on that day since the famous drink is synonymous with the famous horse race. But it’s actually tomorrow. Food Network has a mint julep recipe that it calls “perfect”. Martha Stewart has a recipe too, and something tells me that she considers hers to be even more perfect. You don’t argue with Martha Stewart.

Seriously, don’t argue with Martha Stewart.

Upcoming Anniversaries and Events

Walt Whitman born (May 31, 1819)

The Walt Whitman Archive has everything you need to know about the life and work of the American poet.

Marilyn Monroe born (June 1, 1926)

Here’s a 1956 interview in The Saturday Evening Post with the blonde movie star.

End of the Civil War (June 2, 1865)

The Saturday Evening Post had extensive coverage of the war. Here’s what we had to say about The Battle of Gettysburg, a “half-time” report from 1863, and here are some little known facts about the war.

Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee season 6 premiere (June 3)

This season of the comics-get-coffee show starts off with Jerry Seinfeld’s Seinfeld costar Julia Louis-Dreyfus, then the following weeks we’ll see Jim Carrey, Bill Maher, Steve Harvey, new Daily Show host Trevor Noah, and Stephen Colbert.

Robert F. Kennedy assassinated (June 5, 1968)

The John F. Kennedy Library and Museum site has a biography of the Massachusetts senator, along with transcripts of many of his speeches.

D-Day (June 6, 1944)

SEP Archive Director Jeff Nilsson writes about “The Century’s Best-Kept Secret,” the planned invasion of Nazi-held Europe.

The Genius Who Launched the Martian Invasion

Orson Welles would be pleased; his name is now permanently linked with a national holiday. Halloween has become something of a “feast day” for the producer-actor, whose broadcast of H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds was first heard 75 years ago. Each year at this time, it is replayed on the radio and Web, with added commentary about the massive panic it caused when it originally aired. [Click here to read more about America’s reaction to the broadcast “Are We Ready for a Martian Invasion?”]

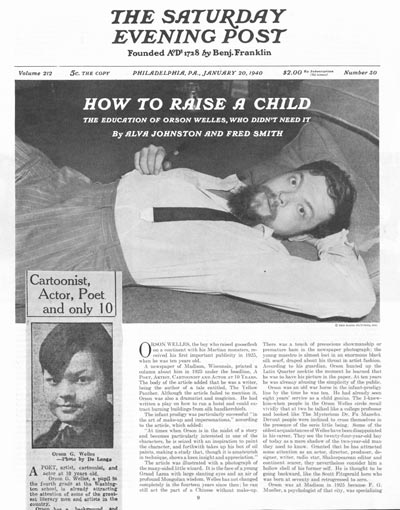

Welles—the revolutionary director of Citizen Kane, the talented Shakespearean actor, and the man who scared Americans into a massive panic in 1938—had an insatiable appetite for attention. His hunger for renown began in his earliest years, when his intelligence won him the flattering attention of adults. His ability to speak in complete sentences at age 2 earned him the reputation of a child genius. By the time he was 4 years old, he was convinced of what doting adults had repeatedly told him: He was destined for greatness. Not yet old enough for school, he was impatient to achieve his destiny. In those early years, “his main ambition was to escape from childhood,” wrote Alva Johnston and Fred Smith in their 1940 series on Welles, “How To Raise A Child.”

By the time he was 10, Welles—ready to set out into the world and support himself on his talent—“eloped” with his foster parents’ daughter, who was also 10. They were eventually found in Milwaukee, living on the coins they earned from singing and dancing on street corners. Returned to his foster parents, he was enrolled in the local public school.

He made no effort to conceal his boredom with the curriculum. One day in the fourth grade, “he announced that he would like to deliver a lecture on ancient and modern art,” wrote Johnston and Smith. “The teacher offered to turn the class over to him. That did not meet his views. He wanted the whole school. This was arranged. Orson gave a 10-minute history of art and then launched into an attack on the school’s methods of teaching art, which, he said, were sterile; instead of encouraging self-expression, they encouraged feeble imitation and produced lifeless copyists.

by Alva Johnston and Fred Smith

Who Didn’t Need It”

by Alva Johnston and Fred Smith

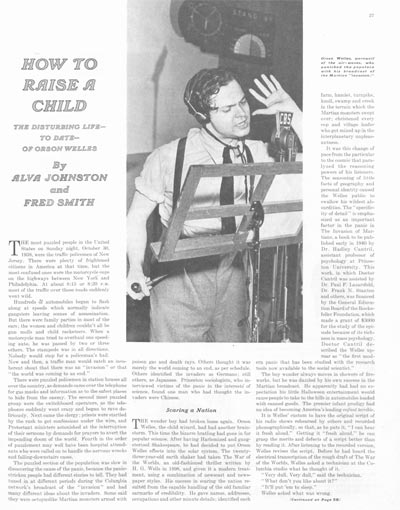

by Alva Johnston and Fred Smith

“‘You mustn’t criticize the public school system, Orson,’ interrupted a teacher.

“‘If the public-school system needs criticizing, I will criticize it,’ he replied.”

That little exchange won him notice in the local paper in Madison, Wisconsin. When interviewed, Welles made it clear that he was a child genius—a “cartoonist, actor, and poet.” Playing on his air of a prodigy, Johnston and Smith observed, “he was already abusing the simplicity of the public.”

Welles was eventually put under the guardianship of a Chicago physician who wanted to develop the boy’s genius. The remaining years of his education were quite informal—little more than Welles educating himself according to his own theories. He developed a remarkable knowledge of ancient history, art, and drama, and considerable skill as a magician. But he saw no need to master basic arithmetic. He was confident at age 10 that “there will always be people around to add and subtract for me.”

Welles grew up without the steadying influence of a stable family. When he was still young, his parents separated, then died. His extended family, which showed little interest in the boy, appears to have been a rare collection of small-town eccentrics.

Johnston and Smith were particularly impressed by Welles’ great aunts. “One was an important topic of conversation in Kenosha [Wisconsin] because she used her electric limousine to run after, not to ride in. She tied herself to the machine by a long rope and took her exercise by using the car as a pacemaker. Another, besides wearing a riding habit at all times, hailed her friends on the streets of Kenosha by lifting an enormous wig and waving it at them. A third is still the subject of speculation; she fell out, of a rickshaw in China and was never heard of again.” Yet another tried to achieve big-city decadence on a small-town budget. She “took baths in ginger ale because, as she told [Welles], it was cheaper than champagne.”

The boy’s inclination toward eccentricity was only encouraged by the adults who kept reminding him of his remarkable intelligence and talent. Surprisingly, Welles never developed into a spoiled brat. “Infant prodigies are usually admired and feared, rather than loved,” wrote Johnston and Smith. “The average prodigy is an arrogant little hellhound. According to the authorities, Orson was not so bad as might have been expected. Ashton Stevens described him as ‘gabby and precocious, but not snooty.’ Others say he was gentle and patient with the absurdities of adults.”

At the age of 16, he had talked his way into leading roles in the theaters of Dublin and London. When he returned to America, though, he found no demand for his acting or his plays. “For the first time in his life he found himself being persecuted with inattention,” Johnston and Smith reported. In Times Square, he was stunned to find large groups of people not mentioning him. A prodigy can only take so much neglect. Welles hopped a steamer and sailed to northern Africa for a change of scenery while writing a book on the plays of Shakespeare.

He returned to New York to find that Broadway had caught up with his European reputation. By age 19, he had several starring roles on Broadway and was starting to work in radio. By age 23, he produced his panic-inducing tale of Martians and death rays.

In the days that followed that October 30, 1938, broadcast, he must have wondered if he’d played his young prodigy card once too often. Hundreds of people were furious with him for both scaring them and then making them feel foolish. He had also made enemies in Hollywood, where he was considered both too young and too talented. “During its first two decades, the picture business was rich in child colossuses,” wrote Johnston and Smith. “It is in the nature of things that the superannuated infant prodigies and their cohorts should disapprove of a fresh young infant prodigy.” Yet here was the 24-year-old Welles being paid more than $150,000 plus percentage for every movie he made, and over $5,000 for each of his weekly radio broadcasts.

The press eventually dropped the story of the broadcast after Welles made an earnest apology. And victims of the hysteria no longer wanted to talk about how they were frightened into a blind panic. The outrage died away. But many Americans continued to regard him with the wary indulgence adults often give children who are too smart for their own good.

Are We Ready for Another Martian Invasion?

by Alva Johnston and Fred Smith

Washington Irving created the first great American legend of Halloween in “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow.” In his short story, a vain, superstitious schoolmaster is so terrorized by a prankster disguised as a headless horseman that he flees his village and never returns.

When actor, writer, and director Orson Welles planned a Halloween broadcast for 1938, he knew Americans weren’t going to be impressed with an imaginary horseman from hell. Instead, he presented horror with a modern tone. His adaptation of H. G. Wells’ War of the Worlds was scrupulously planned to give the impression of an unscripted radio broadcast, with panicked announcers, realistic sound effects, and careful editing. (At one point, a “reporter” at the landing site describes the Martians firing a lethal heat ray that is moving toward him, closer and closer. Suddenly his microphone goes dead and eight seconds of stunned silence pass before a shaken station announcer comes on the air.)

Welles had unlimited faith in his dramatic abilities, but the success he achieved that night was far beyond anything he would hoped to have reached.

“The most puzzled people in the United States on Sunday night, October 30, 1938, were the traffic policemen of New Jersey. There were plenty of frightened citizens in America at that time, but the most confused ones were the motorcycle cops on the highways between New York and Philadelphia. At about 8:15 or 8:20 P.M., most of the traffic over those roads suddenly went wild.”

The account comes from a Post biography from 1940, “How To Raise a Child: The Disturbing Life — to Date — of Orson Welles.”

“Hundreds of automobiles began to flash along at speeds which normally indicate gangsters leaving scenes of assassination. But there were family parties in most of the cars: the women and children couldn’t all be gun molls and child racketeers. When a motorcycle man tried to overhaul one speeding auto, he was passed by two or three others. The stampede was in all directions. Nobody would stop for a policeman’s hail. Now and then, a traffic man would catch an incoherent shout that there was an ‘invasion’ or that ‘the world was coming to an end.’

“There were puzzled policemen in station houses all over the country, as demands came over the telephone for gas masks and information as to the safest places to hide from the enemy. The second most puzzled group were the switchboard operators, as the telephones suddenly went crazy and began to rave deliriously. Next came the clergy; priests were startled by the rush to get confessions under the wire, and Protestant ministers astonished at the interruption of their sermons by demands for prayers to avert the impending doom of the world. Fourth in the order of puzzlement may well have been hospital attendants who were called on to handle the nervous wrecks and falling-downstairs cases.

“Welles had nearly finished the broadcast before he detected that something was wrong. Through a glass partition in the studio he observed the entrance of several policemen, and he also notice unwonted activity at a battery of telephones.

“As soon as the broadcast was over, attendants hurried over to inform him that there were long-distance calls for him.

“The first message was a threat of death from a chamber-of-commerce official of Flint, Michigan, who asserted that the population of Flint had scattered far and wide and that it would take days to reassemble. The next message offered statistics on the number of broken tibias and fibulas in people from Western Pennsylvania. Hundreds of dollars were paid to A.T.& T. that night for the privilege of swearing at Welles. The thing grew serious as the death toll mounted. It was around twenty at ten P.M. Later research indicated that there had been no fatalities, but at the time Welles regarded himself as a mass murderer.”

Irving meant us to smile at his fear-ridden schoolmaster. Welles only wanted to make the flesh creep among his listeners. He never intended to make the broadcast an illustration of how easy it was to stampede Americans.

Much of Welles’ effectiveness, according to his biographer, came from his mixture of the fantastic and mundane.

“His success in scaring the nation resulted from the capable handling of the old familiar earmarks of credibility. He gave names, addresses, occupation and other minute details; identified each farm hamlet, turnpike, knoll, swamp and creek in the terrain which the Martian monsters swept over; christened every cop and village loafer who got mixed up in the interplanetary unpleasantness.

“It was this change of pace from the particular to the cosmic that paralyzed the reasoning powers of his listeners. The seasoning of little facts of geography and personal identity cause Welles’ public to swallow his wildest absurdities.”

In fairness, though, we should consider how the atmosphere of the times contributed to the panic:

• The year was hardly one of reassuring calm. Hitler had taken over control of the German Army, seized Austria and Czechoslovakia, and just a week before Welles’ broadcast, issued his first threat against Poland. Meanwhile, fascist armies were making steady progress over the countrysides of Spain, China, and Africa. Americans could see the next world war over the horizon, and it was moving faster than they thought possible.

• It was hard to confirm or deny rumors. On Sunday evening, when Americans began hearing about Martians, the next newspaper was about 12 hours away. Most Americans couldn’t telephone to confirm the rumors: Only a third of households had phones at the time. Many did tune their radio to the NBC system and The Chase & Sanborn Hour as usual, but for some, this wasn’t enough reassurance.

• The time of year was also important. Autumn seems to awaken a sense of the macabre. Cool days, unexpected twilight, the rustling of dry leaves, and the roar of wind through bare tree limbs have always inspired thoughts of the fantastic and supernatural.

• Lastly, we should bear in mind all the changes Americans of 1938 had seen. The country had lost many of its old certainties, which had insulated prior generations. Americans were living with ideas and technology that wasn’t just impossible when they were young, but unimaginable. If our great bull-market economy could fail, if the government was attempting to repair the market, if Prohibition could be repealed—why wouldn’t we believe that Martians landed in New Jersey?