50 Years Ago: The Unstoppable Oscar Robertson

A half-mile from the office of The Saturday Evening Post, in Indianapolis, sits Crispus Attucks High School, a historically black public school known for distinguished alumni like jazz guitarist Wes Montgomery and U.S. Representative Julia Carson. The school faces Oscar Robertson Boulevard, named for the legendary basketball player who also attended Crispus Attucks and who led his high school team to two consecutive state championship wins in 1955 and 1956. It was the first all-black high school in the nation to win a state title.

A half-mile from the office of The Saturday Evening Post, in Indianapolis, sits Crispus Attucks High School, a historically black public school known for distinguished alumni like jazz guitarist Wes Montgomery and U.S. Representative Julia Carson. The school faces Oscar Robertson Boulevard, named for the legendary basketball player who also attended Crispus Attucks and who led his high school team to two consecutive state championship wins in 1955 and 1956. It was the first all-black high school in the nation to win a state title.

Robertson went on to win a gold medal at the 1960 Olympics before being drafted to the NBA. He played for the Cincinnati Royals for 10 seasons until coach Bob Cousy traded the standout player to the Milwaukee Bucks. It was with the Bucks that Robertson won an NBA championship.

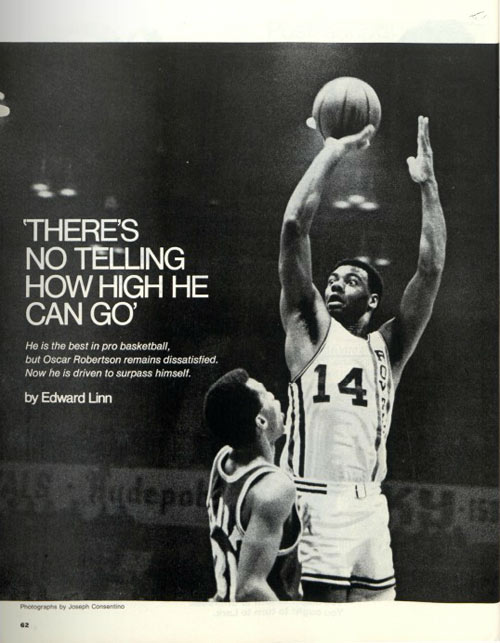

Fifty years ago, a profile of Oscar Robertson appeared in the Post (“There’s No Telling How High He Can Go”) extolling his superiority in every aspect of basketball: “Oscar controls the flow of a game even more than a top quarterback does in football.” His ability to excel in rebounds, assists, and points all at once was unmatched: he was the first player in the NBA to average a triple-double (double digits in three stats) for a season.

In fact, Robertson has three of the only five triple-doubles to take place in NCAA Final Four history. The last was Magic Johnson in 1979, and no player has managed a triple-double since assists became an official statistic in 1984.

But Robertson came from the humblest of beginnings, growing up on the west side of Indianapolis without enough money to buy a basketball. Even after proving his talent, Robertson faced racial prejudice gaining endorsements. In 1968, Robertson said, “I had a big department store — I don’t want to mention the name — ask me to do an ad for them. They wanted to give me 50 dollars. They said I had to remember that this wasn’t New York or Chicago. After they tell me something like that, I wouldn’t appear in their ad no matter what they offered.”

Two years after this article was published, Robertson went on to become the president of the NBA players association and spearheaded an antitrust lawsuit against the NBA that resulted in major changes to their free agency and draft rules and led to higher salaries for the players. After he retired, he focused on improving the living conditions of African Americans in Indianapolis by developing a housing initiative to help families make down payments.

Robertson’s success story parallels that of Crispus Attucks High School itself. Built during an Indiana era of Klan power, the segregated school was designed for failure. Instead, its strong faculty and supportive community created a flourishing legacy. Robertson’s contributions continue to have lasting influence both on and off the court.