The People Nobody Wants: The Plight of Japanese-Americans in 1942

Originally published May 9, 1942

On the fateful day that Lt. Gen. John L. De Witt, chief of the Western Defense Command, ordered the removal of all persons of Japanese blood from the Pacific Coast Combat Zone, chunky little Takeo Yuchi, largest Japanese farmer in “the Salad Bowl of the Nation,” California’s Salinas Valley, was wrangling over the telephone with a produce buyer in San Francisco.

“That fellow purchases for the Navy,” he said, slamming down the phone. “He wants me to grow more Australian brown onions because the Navy needs them. The Army tells us to evacuate our farms right now. Just where do we stand, anyway?”

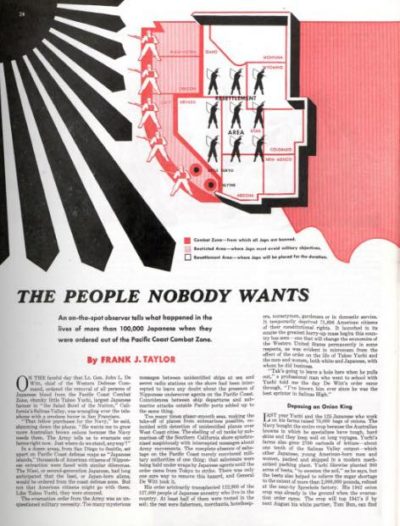

In a dozen areas, from San Diego to Seattle, set apart on Pacific Coast defense maps as “Japanese islands,” thousands of American citizens of Nipponese extraction were faced with similar dilemmas. The Nisei, or second-generation Japanese, had long anticipated that the Issei, or Japan-born aliens, would be ordered from the coast defense zone. But not that American citizens might go with them. Like Takeo Yuchi, they were stunned.

At least half of the 112,905 people of Japanese ancestry affected by the order were rooted in the soil; the rest were fishermen, merchants, hotelkeepers, nurserymen, gardeners, or in domestic service. It temporarily deprived 71,896 American citizens of their constitutional rights. It launched in its course the greatest hurry-up mass hegira this country has seen.

“Tak’s going to leave a hole here when he pulls out,” a professional man who went to school with Yuchi told me the day De Witt’s order came through. “I’ve known him ever since he was the best sprinter in Salinas High.”

Yuchi’s own family, consisting of his alien mother, his Salinas-born wife, his 8-year-old daughter, 6-year-old son, and a baby daughter, is an average California-Japanese household. His wife’s brother, Hideo Abe, is in the Army. His younger brother, Masao, was called in by the local draft board for his physical examination the day I was there. Of the 21,000 Japanese families on the Pacific Coast, one in every five has contributed a son to the Army.

“Well, are you going to go voluntarily or wait until the Army evacuates you?” I asked.

“It’s a tough one to figure out,” Yuchi replied. “I’m American. I speak English better than I do Japanese. I think in English, not Japanese.”

After leaving the Yuchi household, I called on another Nisei, Dr. Harry Y. Kita, a dentist. Prior to Pearl Harbor, Kita, a University of California graduate, enjoyed a thriving practice. Half of the patients who sat in his three chairs were whites. Since then, most of them had been from the Japanese community. “I haven’t much practice left,” said Kita, with a hearty but forced laugh. “I understand why it is,” he continued. “I feel American. I think American. I talk American. My only connection with Japan is that I look Japanese.”

“Could you tell a good Japanese from a bad one?” I asked him.

“No more than you could,” he replied. “But if I knew one who was disloyal to this country, you can bet I’d turn him in.”

Dorothea Lange

Vegetable Wars

From white vegetable growers I heard the other side of the story. The Salinas Vegetable Grower-Shipper Association had just published a brochure titled NO JAPS NEEDED to counteract a widespread impression that Californians would go hungry if the Japanese truck gardeners were removed. The dislike of the militant Grower-Shipper Association for the valley’s Japanese farmers is an old and bitter one. The association is composed of a few score large-scale white growers who lease lands, produce lettuce, carrots, and other fresh vegetables the year round in the Salinas, Imperial, and Salt River Valleys for the Eastern markets. … At one time the lettuce growers, like the sugar-beet growers, depended upon Japanese for field labor. As the Japanese, one by one, became farmers in their own right, and competitors, their places in the field were taken by Mexican or Filipino labor. White men and women, largely Oklahomans, handled the trimming, icing, and crating in the packing plants, but they were never able to endure the back-breaking stoop work in the fields. Only the short-legged Japs could take that.

Shortly after December 7, the association dispatched its managing secretary, Austin E. Anson, to Washington to urge the federal authorities to remove all Japanese from the area. “We’re charged with wanting to get rid of the Japs for selfish reasons,” Anson told me. “We might as well be honest. We do. It’s a question of whether the white man lives on the Pacific Coast or the brown men. They came into this valley to work, and they stayed to take over. … If all the Japs were removed tomorrow, we’d never miss them in two weeks, because the white farmers can take over and produce everything the Jap grows. And we don’t want them back when the war ends, either.”

The Japanese-American loyalty creed, to which all Nisei publicly subscribe, is about to get its first real test, particularly these portions of it: “… I am firm in my belief that American sportsmanship and attitude of fair play will judge citizenship and patriotism on the basis of action and achievement, and not on the basis of physical characteristics. … Although some individuals may discriminate against me, I shall never become bitter or lose faith, for I know that such persons are not representative of the majority of the American people. …” In such a test, the tolerance of the new host states will also feel the fire which has been ignited by the obvious requirements of a stern military emergency.

—“The People Nobody Wants,” Frank J. Taylor,

May 9, 1942

This article is featured in the May/June 2017 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Also read Unwanted: A Teenage Memoir of Japanese Internment from the May/June 2017 issue of The Saturday Evening Post.