I Am the Tooth Fairy

“I know you’re the tooth fairy.” Noah, my 8-year-old, looks me dead in the eye. We are out to dinner. A large television hangs from the wall. Without blinking, he looks back up at the screen. A small, dry wing falls from my back and lands on the floor like a candy wrapper. The thing about not existing is that sometimes it’s a lot like being a mother.

“Sorry, Mama,” says Eli, my 6-year-old. He pats my hand and takes a bite of broccoli.

I think about all the elaborate notes in pink cursive, the 100 hundred shiny pennies in a cloth pouch, the blue stuffed cat, the five-dollar bill, the Superman, the glitter trails, the wooden hearts, the breath I held, the way I ever so gently lifted the pillow, the sparkle-stamped envelope with the tooth fairy’s address: 12345 Tooth Fairy Lane, Moutharctica, Earth. I kept myself secret. I tiptoed. I used my imagination, and now I’ve been caught. Noah looks at me again with a mix of sadness and pity and suspicion. I turn around to see what he’s watching. It’s a cartoon about a sea sponge who lives with his meowing pet snail.

A little light goes out inside me. But I can’t locate exactly what it ever lit up.

After Tinker Bell drinks the poison Hook left for Peter Pan, and her wings can barely carry her, and her light starts fading, and after she lets Peter Pan’s tears run over her finger, she realizes “she can get well again if children believed in fairies.” “Clap your hands; don’t let Tink die,” says Peter Pan. Many children clapped, some didn’t, “a few little beasts hissed.” Tink, of course, is saved. She flashes “more merry and impudent than ever.” It doesn’t even occur to her to thank the children who believed. Tink, whose name sounds like a penny tossed in a glass. Tink, whose name sounds like a wish that won’t come true.

Often as a mother I am in a cold sweat juggling whimsy and delight. “Magic anyone? Endless fun? Astounding joy?”

“No,” say my sons, “we’re good.” And they are. It’s me who isn’t good. It’s me who wants it. And I don’t even want it.

Often as a mother I am in a cold sweat juggling whimsy and delight. “Magic anyone? Endless fun? Astounding joy?”

What I want is my sons’ illegible, lyrical teeth. I want to turn them into an alphabet just for us. Letters with crowns and necks and roots. Milk letters. Deciduous letters. In this language I would draw a map that clearly marks where my sons’ wonder is buried so they always know where to go on their coldest days.

Clap your hands; don’t let mother die. My sons clap their hands and I brighten.

I’ve never seen a fairy. I’ve never looked up and seen a faint green glow. The closest I’ve ever come was once as a child — in a dream — I ran after myself, and when I caught up to me and turned around I wasn’t there.

We take shelter in children to escape oblivion. We ask the child to drag around the unwieldy weight of magic. To clap wildly. To believe in what we believe in no longer. We ask the child to keep the awe we forgot how to hold. The fairy isn’t the fairy. It’s the child who is the fairy. It’s the child who is enchanted, a metaphor, a shape-shifter. My sons keep bursting out of their skin. They smell like poppies, warm earth, milk. And then one day, out of nowhere, they won’t anymore. They are losing their baby teeth at what seems an alarming rate. Adult teeth bloom in their mouths. Their limbs grow longer and longer like shadows.

For whom is a child’s childhood? I think it’s for all of us. But it’s not for when we are children. Our childhoods are for later.

Some believe fairies are the discarded gods of the oldest faiths. Like shed skins of light. They continue to exist because they believe, like a child, that they exist.

The fairy isn’t the fairy. The mother is the fairy. The fairy flits back and forth, uncatchable. Who is she? The fairy is the space between knowing and not knowing. It’s the realization as it dawns. It’s what glows between a mother and her child. It’s Puck sweeping the dust with a broom behind the door. The fairy is the dust. The fairy is the door.

In 1691, Robert Kirk, a minister in the Church of Scotland, wrote a treatise claiming fairies were as real as you or me. It wasn’t published, though, until 1851, when “The Secret Commonwealth” was printed in a limited edition of a hundred copies. We each, he wrote, have a fairy counterpart, a co-walker, an echo. He described fairies as “somewhat of the nature of a condensed cloud and best seen in twilight.” Their bodies are spongeous and thin. “They are sometimes heard to bake bread.” “They speak but little and that by way of whistling — clear, not rough.” “They hang between the nature of God, and the nature of man.” Their body is “as a sigh is.”

They do not curse, but among their common faults are “Envy, Spite, Hypocrisy, lying, and dissimulatione.” They are prone to sadness because of their pendulous state. They can cure a sick cow. They steal milk, and when they are very angry they spoil it.

On May 14, 1692, Reverend Kirk took a walk in his nightgown on the fairy hill beside the manse. Later that evening, on the same hill, his body was found dead. The body that was buried, according to locals, was a changeling. The fairies had kidnapped the minister in his nightgown, replaced him with a dead fairy, and held the reverend captive in Fairyland.

The punishment, it seems, for believing too much in fairies is to be snatched away by them for eternity.

Three days after I give birth to Noah, I am nursing him in a soft, beige rocking chair when a goat walks in. “Hello,” I say. The goat, being a goat, says nothing. Most likely, I am hallucinating from no sleep. Most likely, a little piece of this world has torn and through the rip a goat has walked in. The goat lays his soft head on Noah’s head, like a kiss. The room fills up with wildflowers and then empties of wildflowers and then the goat is gone. Who am I to say there is no thin veil between this world and fairyland? I know this now, but I didn’t know it then: I am the tooth fairy.

This is how you can tell if your baby has been replaced by a changeling: boil water in an eggshell. If your baby is a changeling it will laugh and reveal it’s as old as the forest. In all its years, it will say when it suddenly begins to speak, it has never seen anyone boil water in an eggshell. If you wish to keep the fairies away, put the Bible, a piece of bread, or iron in your child’s bed. And if you wish to see a fairy, take the rope that once bound a corpse to a bier and tie it around your waist. Bend over and look between your legs. A procession of fairies will appear. If the wind changes directions while you do this, it is possible you will drop down dead.

There are two kinds of fairies. There are the “trooping” fairies, who live together on a hill. And then there are the ones who attach themselves to individuals, like a haunt. If I were a fairy, I’m certain I’d be the second kind, but to tell you the truth I’d make a terrible fairy. A terrible mother fairy who writes about fairies, and by doing so angers them all.

We are at the pediatric dentist because Eli has flown off his scooter and landed on his face. The dentist, who looks more like a very old child dressed up as a dentist than an actual dentist, puts Eli in a chair and raises it with a crank to the ceiling. She climbs up a ladder and examines him in the air. “You okay?” I call out from down here. From all the way down here. She tells me his two front teeth will have to be pulled. “Bad news,” she says, smiling. She lowers Eli and climbs back down. She hands me a brochure on sedation options. She is wearing tiny pink sneakers. I imagine a back room filled with sparkling white teeth. Nightly she grinds them. And stirs the powder into her warm milk. Unlike the rest of us, she will live forever.

“Can we err on the side of nature?” I ask. “I don’t recommend that,” says the dentist who clearly was once a fairy.

She shows me two fake front baby teeth attached to a wire. After she pulls Eli’s teeth she can “cement the device into his mouth,” she says. “I made one for my daughter,” she says, her red cheeks glowing.

The dentist’s office is decorated like an amusement park: vending machines filled with toys, televisions frantic with cartoons, posters of wide-eyed animals in pants. The instruments on the dentist’s tray — forceps, mouth mirror, periodontal probe — shine as the only reminder of where we are. There is even a giant stuffed panda. All you need to do is leave your name and number on a small piece of paper for the chance to win. I am so distraught I almost enter. Would she deliver the panda herself? Would she knock on our door with the prize and then devour us?

“Let’s get out of here,” I say to Eli. “Let’s run, Mama,” says Eli. And we run. We run home where it’s safe. Eli’s baby teeth stay in for another year. And when they fall out naturally I add them to the rest. Between Noah and Eli I have twelve. Twelve teeth. Sometimes I just hold them. Noah’s in one hand. Eli’s in the other. Proof of their babyhood. Proof of the mouths they left behind. Those baby mouths that spoke words thickly accented by the land they came from. Maybe it’s those teeth that are the fairies. The ones the children, in order to grow, must cast off. The teeth that made little holes in the air with new breath.

If I were really the tooth fairy, I’d lay each tooth, like a body, on a rose leaf. I’d carry them one by one over my head through the streets. The air would brighten, and grow sad and sweet. And I would sing, though I cannot sing, a lament for everything I must remember and everything my sons must forget.

Last night I slept with all my sons’ teeth underneath my pillow. And when I woke up, Noah and Eli were leaving me notes. They each had a long white beard, and they were very old and wise and radiant. I had caught them. And then I woke up again.

First published in The Paris Review Daily.

This article is featured in the November/December 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Take the Fair Face of Woman, and Gently Suspending, with Butterflies, Flowers, and Jewels Attending, thus Your Fairy is Made of Most Beautiful Things by Sophie Gengembre Anderson (1869)

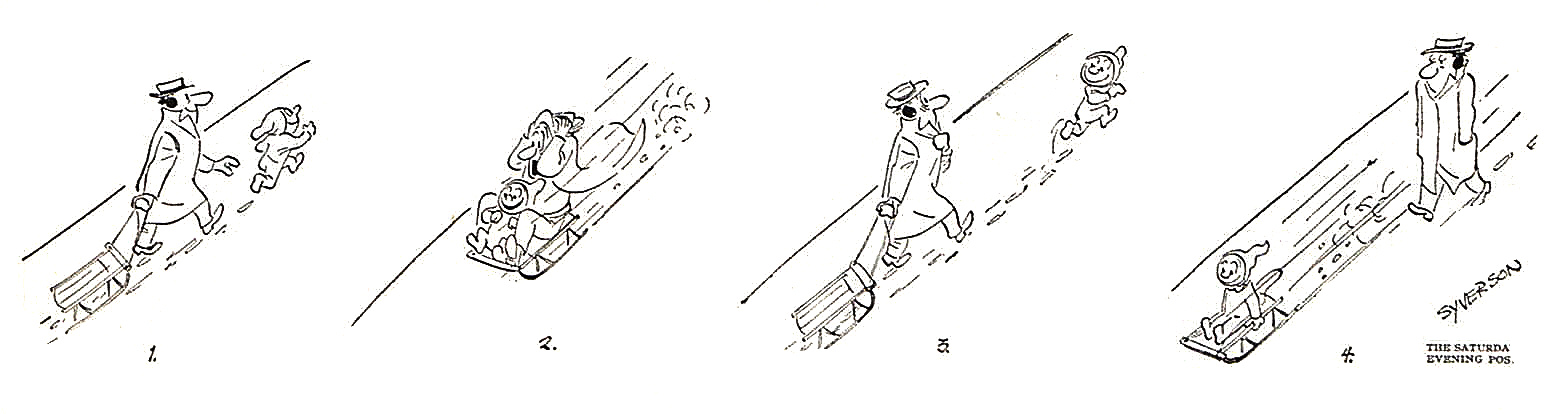

Cartoons: Babysitter Blather

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Zeis

June 4, 1955

Lepper

April 19, 1952

Clara Gee Kastner

April 10, 1954

Locke

January 19, 1952

Ben Roth

September 15, 1951

Salo

June 14, 1952

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

“The Kids These Days!” or “The Parents Just Don’t Get It!”

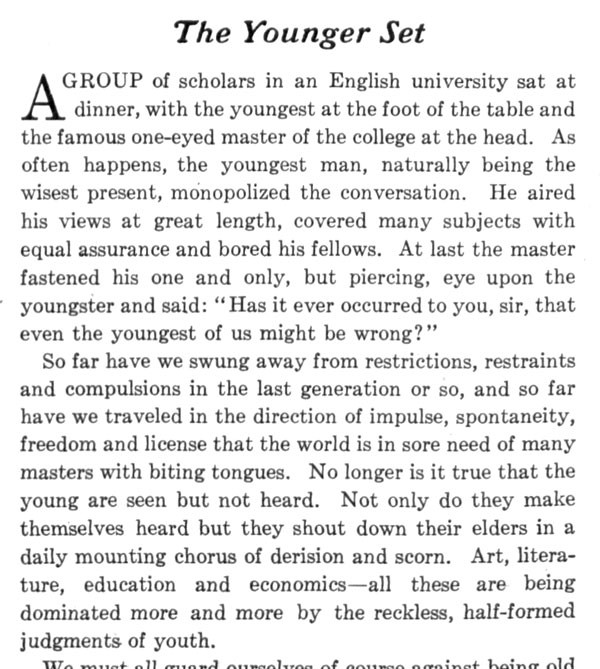

—The following is from “The Younger Set,” Editorial, September 4, 1920

No longer is it true that the young are seen but not heard. Not only do they make themselves heard but they shout down their elders in a daily mounting chorus of derision and scorn. Art, literature, education, and economics — all these are being dominated by the reckless, half-formed judgments of youth.

Progress would die if old men always had their way. But it is no sign of settled brain paths to be aware of the rampage on which youth has of late been engaged. The meaningless smudge and blur that makes up so much of modern art; the strange, tortured language which so many of the younger, newer writers use in place of English; and the rediscovered and previously discarded utopias which a host of youthful reformers are so joyfully recommending — are these not signs that youth has been given — or has taken — its head with a vengeance?

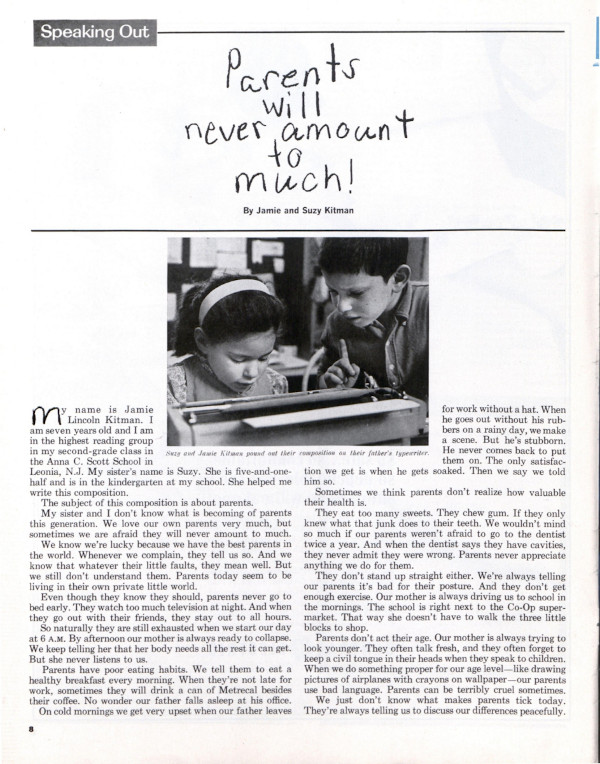

—The following is from “Parents Will Never Amount to Much!” December 19, 1964

My sister and I don’t know what is becoming of parents this generation. We love our own parents very much, but sometimes we are afraid they will never amount to much.

We know that whatever their little faults, they mean well. But we still don’t understand them. Parents today seem to be living in their own private little world.

Even though they know they should, they never go to bed early. They watch too much television at night. And when they go out with their friends, they stay out to all hours.

Parents have too much freedom these days. They are always thinking of ways to get away from us. When our mother goes on a business trip with our father, why do they always take their bathing suits?

We don’t know where our parents picked up all their bad habits. Certainly not from us. It’s probably their friends. We don’t approve of their friends. They wear too much makeup and they drink.

Sometimes we’re afraid we spoil parents by letting them have their way.

—“Parents Will Never Amount to Much” by Jamie and Suzy Kitman, December 19, 1964

Featured image: Everett Collection / Shutterstock

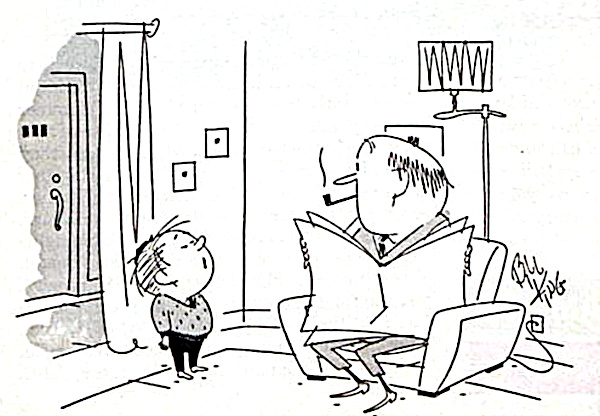

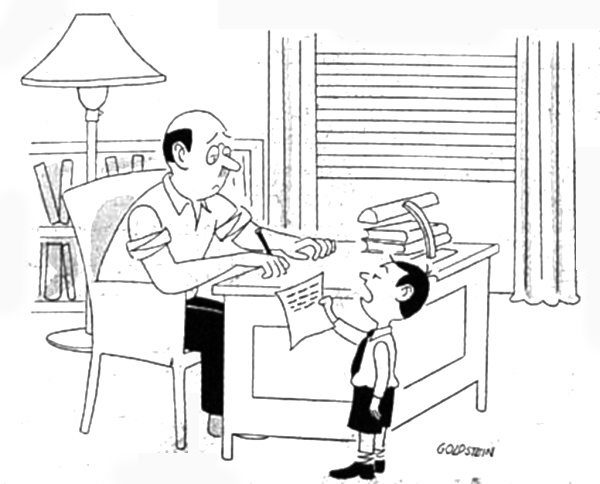

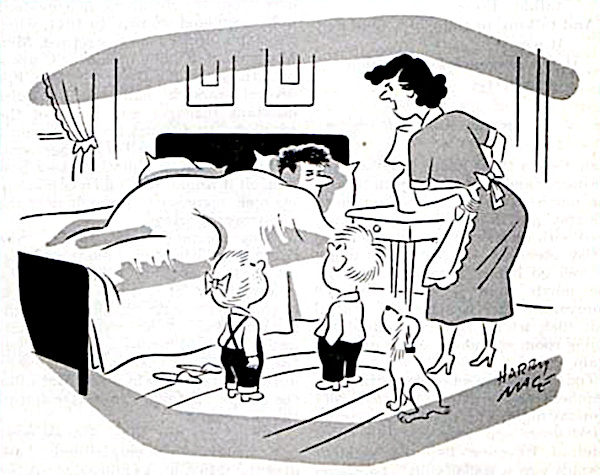

Cartoons: Father’s Day

Les Colin

December 9, 1950

Don Tobin

December 9, 1950

Bill King

December 25, 1950

Goldstein

November 25, 1950

Ray Heller

November 18, 1950

Stan Hunt

October 22, 1950

Hoff

October 14, 1950

Harry Mace

January 13, 1951

December 9, 1950

How to Document Your Child’s Life Without Plastering It All over Social Media

Have you been “sharenting?”

The common practice of releasing a torrent of photos, videos, and stories of your children on social media can be difficult to resist. After all, they mean so much to you. “What kind of cold-hearted cretin wouldn’t want to see my 13th post in a day of little Jaxon’s romp in the autumn leaves?” you may be asking yourself.

But, even if your “sharenting” is welcomed by others — like, say, hundreds of thousands of followers — you might be creating an unwanted digital footprint for your child that they can’t even consent to yet. This concern is particularly timely after mommy bloggers, like the one who wrote recently in The Washington Post, have expressed dismay at their growing children’s reactions to having intimate details of their lives documented online.

While you may not have the wide internet reach of an Instagram influencer or a famous blogger, there are plenty of other privacy and safety concerns to consider when posting about your kids. For many of us, social media sites have become the main channel for storing our memories, but is there a better way?

Change Up the Apps

If you really want to hang on to your Facebook, there are some privacy changes you can make to better secure your family’s digital life. Making private photo albums and posts is a way to limit the people who see your content. Of course, you can’t have absolute control over the content once it is released, but you can feel better, perhaps, about who is seeing your pictures and stories.

Another app, called Keepy, was originally developed for saving and sharing kids’ artwork. The platform has grown, however, and the app can now be used for keeping a collection of pictures, videos, and voiceovers to share with loved ones. Grandparents, aunts, and friends can even leave their own “voice message” style comments, and the whole gallery can be viewed from any device.

If you like the “story” video form that has taken over social media sites of late, then you might be interested in Steller, an app that lets you combine photos, videos, and text into digital flipbooks that tell your story. You can then share your flipbooks via texting, e-mail, or virtually any other form of online communication. Steller is used largely for travel and marketing stories, but the burgeoning social media platform offers an easy way to tell your family’s stories and share them however you like.

A few apps now make it possible — and simple — to print your pictures in the most exciting ways. With Postagram, you can mail a personalized postcard to just about anywhere in the world for $2 domestically and $3 internationally. Send a vacation greeting, holiday card, or just a casual “hello” with your own pictures and text without messing with postage stamps. The app Recently sends you a magazine each month featuring your own photos. For about the price of a Netflix subscription, you can turn your beautiful iPhone or Android snapshots into a glossy zine where your family is always the cover story.

Go Primitive

Before Facebook and Instagram and even e-mail, there were still methods of saving family pictures and stories. People got creative, and they didn’t have to worry that their years of memories might disappear with the downfall of some app.

If you want to go old school with your archiving, spring for a vintage photo album like the offerings at MochiThings or Wayfair. Organizing and filling your albums could be a fun family activity, and you can display them prominently in your home where friends can peruse them at will. It may not give the immediate dopamine rush that you feel when those “likes” come rolling in on Facebook, but it could feel more lasting and special.

Another fun alternative to posting is to keep a memory jar somewhere handy in the house. Whenever a significant (or totally insignificant) memory is made, jot it down on a strip of paper and toss it in the jar. At the end of the year, you can read all of the experiences you had and put them somewhere safe.

For the long-winded among us, letter-writing can be an intimate proxy for blogging. A friend told me she writes regular letters to her toddler detailing the fun and troubles of the day. She plans to bundle them up and give them to him someday when he is able to read them. This could work on a weekly or even monthly basis. If you write daily letters to your tot, take into account the heavy lifting that will involve to gift it to them later, and consider paring them down occasionally.

What are your favorite ways to save memories, online or offline? Let us know in the comments.

Featured image: Shutterstock