Remembering My Father and World War I

Veterans Day. At 11 a.m. a wreath is laid at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier at Arlington National Cemetery, marking the hour the fighting ended in World War I — November 11th — known originally as Armistice Day.

At the eleventh hour on the eleventh day of the eleventh month in 1918, the guns on the Western Front fell silent, ending one of the greatest military slaughters in world history.

British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan (1957-1963) said one time that the only reason he was prime minister was that all the men of his generation who would have been had been left on the battlefields of France.

World War I was called — no doubt out of hope — “The War to End All Wars.”

It obviously did not end all wars. See the history books for World War II, Korea, Vietnam, Iraq (two wars there), Afghanistan, and a distressingly long list of others. But the Armistice did stop the carnage wrought by the old principle of battle — to have your men attack the other side’s battle line. In World War I, with fixed positions and lines, those attacks came in waves, day after day, night after night — across a barren expanse known as “No Man’s Land” — into withering fire from the modern machine gun.

The carnage inspired a poem by a Canadian doctor, Lieutenant Colonel John McCrae, written shortly after he lost a friend at Ypres in the spring of 1915, when he saw poppies growing in the battle-scarred field:

In Flanders fields the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below.

We are the Dead. Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie,

In Flanders fields.

The doctor’s poem, “In Flanders Fields,” resonated.

To the point that 20 years later, when I was a little girl, artificial red poppies — usually red paper flowers for the lapel — were a common sight on Armistice Day, made by the American Legion to benefit veterans. They were often sold by veterans on the streets, a bit like the Santas who ring their bells by the Salvation Army black kettles at Christmas.

When I was a little girl, I also remember the casing of an artillery shell that stood on the end table in our living room, like an empty, unused flower vase. Shiny metal, brass I think, perhaps 16 inches high and four or five inches round.

It took a few years for me to link the unusual metal thing on the end table to the story my father, who served in World War I, liked to tell about being sent overseas and writing home to tell his mother where he was stationed. She was so relieved to learn he’d not been sent up to the front, that he would be “safe” stationed at an ammunition dump. She failed to appreciate the dangers.

These World War I incidents and memorabilia were part of my childhood.

When people spoke of “the war” back then, it was World War I. Years later, “the war” became World War II. And still is to “The Greatest Generation.”

I may be a child of “The Greatest Generation,” but my childhood memories are of World War I, its songs playing on the radio still. The sad “Roses of Picardy.” Or, “There’s a long, long trail a winding … into the land of my dreams.” George M. Cohan’s “Over There” was still played sometimes and, occasionally, a whimsical offering by Irving Berlin, who would later give us “God Bless America.” An expression of the everyday soldier starting his day of service to his country, “Oh, how I hate to get up in the morning.”

“Roses of Picardy” by Mario Lanza (Uploaded to YouTube by Megamusiclover1234)

Music was a natural part of my memories. My father played the saxophone in a band in his college years, and during the interregnum in France. I think that the guys in the band, or most of them, went off to war together, played overseas together, and returned to college — this time the University of Michigan — together. I know they took basic training at Fort Benning, Georgia, for my father often told the story of the time they played for a local town dance.

They were going through their usual repertoire, which included a medley they went into as easily as they’d done a hundred times before. But this time they were only a few bars into one of the songs when the dancers paused and turned in their respective places on the dance floor to glare at the band with downright mean stares. They then stalked off the dance floor, often with a parting angry glance over their shoulders.

Too late Daddy and his buddies realized they were playing “Marching Through Georgia.”

As a friend of mine from Georgia said, speaking of that time, “There were still grandmothers in town who remembered Sherman.”

Daddy often talked about places he visited before being shipped home. Nothing like a Cook’s Tour of France and its close neighbors, but I remember his mentioning the town of Nancy and/or Nantes. And he ventured, although not too deeply, into the Alps.

He returned, as noted, and transferred to the University of Michigan, where he met my mother. And his life slipped into that of a young man embarking on his life in his early twenties.

Not all the veterans of World War I were so fortunate. Those who had left their jobs to serve their country returned to find their jobs had been permanently filled. And it left such a stain that the United States Congress decreed — formally written into law — that those who served in World War II (and all subsequent wars) would get their jobs back when they returned.

Not just a job. The job they’d had.

When I started at the Chicago Daily News as a copygirl in December 1944, there were around six female reporters my first year. They had been hired to replace the guys who were away fighting for their country. When the war ended and the guys returned, two of the women were so good they were kept on, and the staff expanded. The others cleaned out their desks and the guys who’d once been there sat down at their typewriters as before.

Congress also promised anyone who served a college education, in what came to be known as the G.I. Bill. And with the war’s end, colleges and universities across this country changed once again: during the war, regular students had been replaced by servicemen learning about pre-flight training, navigation, the fine art of a bomb sight; after the war, students found their ranks expanded by former G.I.s taking advantage of the opportunity to get a college degree.

It may be common today. But it was a rarity before World War II.

The G.I. Bill also made it possible for veterans to buy homes with little or no down payment and the government backing the mortgage. That’s why the Levitt towns and subdivisions with all those cul de sacs sprouted outside cities. Hundreds and hundreds and still more hundreds of veterans were able to buy homes.

In that respect, beyond the political alliances and treaties and missteps that led to World War II and its legacy, World War I had a major impact on life in this country. Everyday life. The determination to do right — this time — by all those who had served.

And today it’s almost forgotten. Only the anniversary date of its end is remembered, and it’s no longer Armistice Day.

Now it’s Veterans Day.

But still a day to pause — particularly, at 11 a.m. — to remember those who served.

Which is what this nation does.

In fact, some years ago when Congress decided that holidays should, whenever possible, be celebrated on Mondays so people could enjoy long weekends, the outcry from veterans and veterans’ groups about changing Veterans Day was so great that Congress had to change the date back to November 11. It wreaked havoc for a couple of years, however, because of the calendars that had been printed before the outcry.

A small price to pay, however, for a national holiday of such significance being observed on its anniversary date.

From those long ago days of childhood and the story about playing “Marching Through Georgia” to a reunion long years after the end of World War II, I remember Daddy talking about the war. Teaching me a few French words (not parlez-vous Francais?). And threaded through it all, his buddies.

They were just names to me until they gathered once again in our home in Wilton, Connecticut, one beautiful day in 1960, and brought new meaning to the word reminisce.

A happy time, created out of war time.

Featured image: Mike Pellinni / Shutterstock

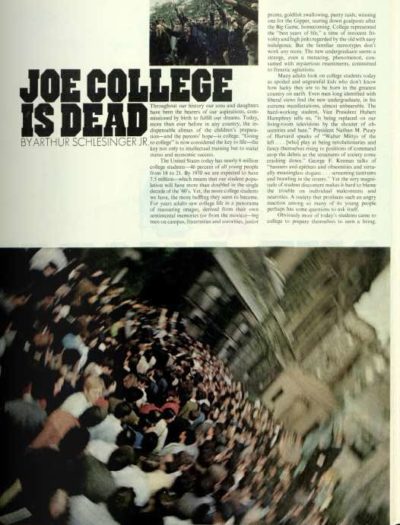

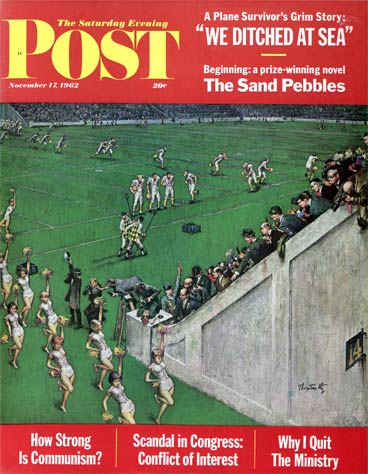

Joe College Is Dead: The Root of Student Unrest in the 1960s

[Editor’s note: Arthur Schlesinger Jr.’s “Joe College Is Dead” was first published in the September 21, 1968, edition of the Post. We republish it here as part of our 50th anniversary commemoration of the Summer of Love. Scroll to the bottom to see this story as it appeared in the magazine.]

Miriam Bakser, © SEPS

Throughout our history, our sons and daughters have been the bearers of our aspirations, commissioned by birth to fulfill our dreams. Today, more than ever before in any country, the indispensable climax of the children’s preparation — and the parents’ hope — is college. “Going to college” is now considered the key to life — the key not only to intellectual training but to social status and economic success.

The United States today has nearly 6 million college students — 46 percent of all young people from 18 to 21. By 1970 we are expected to have 7.5 million — which means that our student population will have more than doubled in the single decade of the ’60s. Yet, the more college students we have, the more baffling they seem to become. For years, adults saw college life in a panorama of reassuring images, derived from their own sentimental memories (or from the movies) — big men on campus, fraternities and sororities, junior proms, goldfish swallowing, panty raids, winning one for the Gipper, tearing down goalposts after the Big Game, homecoming. College represented the “best years of life,” a time of innocent frivolity and high jinks regarded by the old with easy indulgence. But the familiar stereotypes don’t work anymore. The new undergraduate seems a strange, even a menacing, phenomenon, consumed with mysterious resentments, committed to frenetic agitations.

Many adults look on college students today as spoiled and ungrateful kids who don’t know how lucky they are to be born in the greatest country on earth. Even men long identified with liberal views find the new undergraduate, in his extreme manifestations, almost unbearable. The hard-working student, Vice President Hubert Humphrey tells us, “is being replaced on our living-room televisions by the shouter of obscenities and hate.” President Nathan M. Pusey of Harvard speaks of “Walter Mittys of the left … [who] play at being revolutionaries and fancy themselves rising to positions of command atop the debris as the structures of society come crashing down.” George F. Kennan talks of “banners and epithets and obscenities and virtually meaningless slogans … screaming tantrums and brawling in the streets.” Yet the very magnitude of student discontent makes it hard to blame the trouble on individual malcontents and neurotics. A society that produces such an angry reaction among so many of its young people perhaps has some questions to ask itself.

Obviously most of today’s students came to college to prepare themselves to earn a living. Most still have the same political and economic views as their parents. Most, until 1968, supported military escalation in Vietnam. Most believe safely in God, law and order, the Republican and Democratic parties, and the capitalist system. Some may even tear down goalposts and swallow goldfish, if only to keep their parents happy.

Yet something sets these students apart from their elders — both in the United States and in much of the developed world. For this college generation has grown up in an era when the rate of social change has been faster than ever before. This constant acceleration in the velocity of history means that lives alter with startling and irresistible rapidity, that inherited ideas and institutions live in constant jeopardy of technological obsolescence. For an older generation, change was still something of a historical abstraction, dramatized in occasional spectacular innovations, like the automobile or the airplane; it was not a daily threat to identity. For our children, it is the vivid, continuous, overpowering fact of everyday life, suffusing every moment with tension and therefore, for the sensitive, intensifying the individual search for identity and meaning. The very indispensability of a college education for success in life compounds the tension; one has only to watch high-school seniors worrying about the fate of their college applications.

Nor does one have to be a devout McLuhanite to accept Marshall McLuhan’s emphasis on the fact that this is the first generation to have grown up in the electronic epoch. Television affects our children by its rapid and early communication to them of styles and possibilities of life, as well as by its horrid relish of crime and cruelty. But it affects the young far more fundamentally by creating new modes of perception. What McLuhan has called “the instantaneous world of electric informational media” alters basically the way people perceive their experience. Where print culture gave experience a frame, McLuhan has argued, providing it with a logical sequence and a sense of distance, electronic communication is simultaneous and collective; it “involves all of us all at once.” This is why the children of the television age differ more from their parents than their parents differed from their own fathers and mothers. Both older generations, after all, were nurtured in the same typographical culture.

Another factor distinguishes this generation — its affluence. The postwar rise in college enrollment in America, it should be noted, comes not from any dramatic increase in the number of youngsters from poor families but from sweeping in the remaining children of the middle class. And for these sons and daughters of the comfortable, status and affluence are, in the words of student radical leader Tom Hayden, “facts of life, not goals to be striven for.” This puts many students in a position to resist economic pressures to buckle down and conform. As another radical has written, “Our minds have been let loose to try to fill up the meaning that used to be filled by economic necessity.”

The velocity of history, the electronic revolution, the affluent society — these have given today’s college students a distinctive outlook on the world. And a fourth fact must not be forgotten: that this generation has grown up in an age of chronic violence. My generation has been through depressions, crime waves, riots and wars; but for us episodes of violence remain abnormalities. For the young, the environment of violence has become normal. They are the first generation of the nuclear age — the children of Hiroshima. The United States has been at war as long as many of them can remember — and the Vietnam war has been a particularly brutalizing war. Most students have come to feel that the insensate destruction we have wrought in a rural Asian country 10,000 miles away has far outrun any rational assessment of our national interest. Within the United States, moreover, they have lived with the possibility, as long as many of them can remember, of violence provoked by racial injustice. Even casual crime has acquired a new dimension. Some have never known a time when it was safe to walk down the streets of their home city at night. Above all, they have seen the assassinations of three men who embodied the idealism of American life. The impact of this can hardly be overstated. And — let us face it — our national reaction to these horrors has only strengthened their disenchantment: brief remorse followed by business as usual and the National Rifle Association triumphant.

The combination of these factors has given the young both an immediacy of involvement in society and a sense of their individual helplessness in the face of the social juggernaut. The highly organized modern state undermines their feelings of personal identity by threatening to turn them all into interchangeable numbers on IBM cards. Contemporary industrial democracies stifle identity in one way, Communist states in another, but the sense of impotence is all-pervasive among the young. So too, therefore, is the desperate passion to reestablish identity and potency by assaults upon the system.

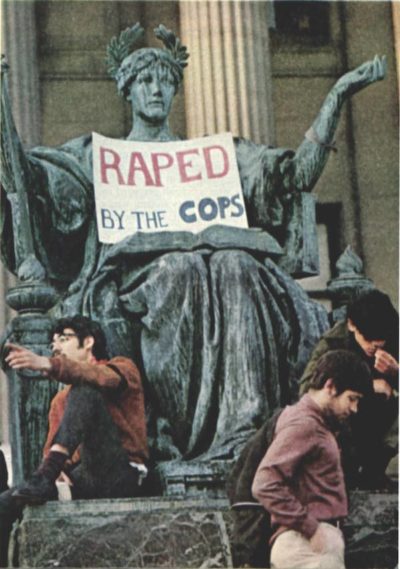

Such factors have set off the guerrilla warfare of students against the existing structures of society not only in the United States but throughout the developed world. (Student unrest in underdeveloped countries is more predictable and has different sources.) Uprisings at Berkeley and Columbia are paralleled by uprisings at the Sorbonne and Nanterre, in the universities of England and Italy, in Spain and Yugoslavia and Poland, in Brazil and Japan and China. Every country can offer local grievances to detonate local revolts. But these are only the pretexts for the rebellion. They are the visible symbols for what the young perceive as the deeper absurdity and depravity of their societies.

American undergraduates first fixed on racial injustice as the emblem of a corrupt society. But in the last two years, resistance to the draft has provided a main outlet for undergraduate revolt.

Until very recently, most college students supported the war in Vietnam — so long as other young men were fighting it. It used to exasperate Robert Kennedy when he asked college audiences in 1966 and 1967 what they thought we should do in Vietnam — hands waving for escalation — and then asked what they thought of student deferment — the same hands waving for a safe haven for themselves. At last, as the draft began to cut deeper, the colleges began to think about the war; and the more they thought about it, the less sense it made.

No one should underestimate the magnitude of this new anti-draft feeling. In 1968, I have not encountered a single student who still supports military escalation in Vietnam. Not all students who hate the war burn draft cards or flee to Canada. Many — and this may be as courageous a position as that of defiance — feel, after conscientious consideration, that they must respect laws with which they disagree, so long as the means to change these laws remain unimpaired. Yet even they regard with sympathy their friends who choose to resist. One who is himself prepared to go to Vietnam said to me, “Every student wants to avoid the draft. Every student, realizing that the method to this end is very individual, respects any method that works — or attempts that do not.”

The anti-draft revolt somewhat diminished this year after President Johnson’s March 31st speech, the Paris negotiations and the McCarthy and Kennedy campaigns. But it will resume, and with new ferocity, if the next President intensifies the war. In April, The New York Times carried a four-page advertisement headed: “We, Presidents of Student Government and Editors of campus newspapers at more than 500 American colleges, believe that we should not be forced to fight in the Vietnam war because the Vietnam war is unjust and immoral.” In June, a hundred former presidents of college student bodies joined campus editors to declare, “We publicly and collectively express our intention to refuse induction and to aid and support those who decide to refuse. We will not serve in the military as long as the war in Vietnam continues.”

However, if we Americans blame the trouble on the campuses just on the war (or, to take another popular theory, on permissive ideas about childrearing), we will not understand the reasons for turbulence. After all, the students of Paris were not rioting against a government that threatened to conscript them for a war in Vietnam; nor are the students of Poland, Spain, and Japan in revolt because their parents were devotees of Dr. Spock. The disquietude goes deeper, and it was well explained by, of all people, Charles de Gaulle. The “anguish of the young,” the old general said after his own troubles in June with French students, was “infinitely” natural in the mechanical society, the modern consumer society, because it does not offer them what they need, that is, an ideal, an impetus, a hope, and I think that ideal, that impetus, and that hope, they can and must find in participation.

Not every American student exemplifies this anguish. It appears, for example, more in large colleges than in small, more in good colleges than in bad, more in urban colleges than in rural, more in private and state than in denominational institutions, more in the humanities and social sciences than in the physical and technological sciences, more among bright than among mediocre students. Yet, as anyone who lectures on the college circuit can testify, the anguish has penetrated surprisingly widely — among chemists, engineers, Young Republicans, football players, and into those last strongholds of the received truth, the Catholic and fundamentalist colleges.

How to define this anguish? It begins with the students’ profound dislike for the impersonal society that produced them. The world, as it roars down on them, seems about to suppress their individualities and computerize their futures. They call it, if they vaguely accept it, “the rat race,” or, if they resist it, “The System” or “The Establishment.” They see it as a conspiracy against idealism in society and identity in themselves. An outburst on a recent Public Broadcast Laboratory program conveys the flavor. The System, one student said, hits at me through every single thing it does. It hits at me because it tells me what kind of a person I can be, that I have to wear shoes all the time, which I don’t have on right now. … It hits at me in every single way. It tells me what I have to do with my life. It tells me what kind of thoughts I can think. It tells me everything.

Another student added, with rhetorical bravado, “Regardless of what your alternatives are, until you destroy this system, you aren’t going to be able to create anything.”

The more typical expression of this mood is private and quiet. It takes the form of an unassuming but resolute passion to seize control of one’s own future. My generation had the illusion that man made himself through his opportunities (Franklin D. Roosevelt); but this era has imposed on our children the belief that man makes himself through his choices (Jean-Paul Sartre). They now want, with a terrible urgency, to give their own choices transcendental meaning. They have moved beyond the Bohemian self-indulgence of a decade ago — Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac. “We do not feel like a cool swinging generation,” a Radcliffe senior said this year in a commencement prayer. “We are eaten up by an intensity that we cannot name. Somehow this year, more than others, we have had to draw lines, to try to find an absolute right with which we could identify ourselves. First in the face of the daily killings and draft calls … then with the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Senator Kennedy.”

The contemporary student generation can see nothing better than to act on impulses of truth: “Ici, on sponlane,” as a French student wrote on the walls of his college during the Paris insurgency. They are going to tell it, as they say, like it is, to reject the established complacencies and hypocrisies of their inherited existence. One student said to me:

Basically, the concept of this “do your thing” bit, as ludicrous as it sounds, may be the key to the matter. What it means is similar to Mill’s On Liberty because it allows anybody to do what he wants to do as long as it does not intrude on anyone else’s liberty. Therefore, nobody tries to impose anything on anybody, nor do they not accept a Negro, a hippie, a clubby, etc. I really believe that today we see beyond superficial appearances and thus, in the end, will have a society of very divergent styles, but it will be successfully integrated into a really viable whole. . . . We test out old thoughts and customs and either dispose of them or retain them according to their merits.

Along with this comes an insistence on openness and authenticity in personal relationships. A 1968 graduate — a girl — puts it clearly:

I think in personal conduct people admire the ability to be vulnerable. That takes a certain amount of strength, but it is the only thing which makes honesty and openness possible. It means you say the truth and somehow leave open a part of your way of thinking. Of course, you cannot be vulnerable with everyone or you would destroy yourself — but it is the willingness to be open, not just California-cheerful open, which is almost a mask since it is on all the time, and therefore cannot be truthful. It is a little deeper than that. … It means being strong enough to reveal your weaknesses. This willingness to be vulnerable — and those you are vulnerable with are your friends — coupled with ability to be resilient, to be strong but supple, those are good qualities, because inherent in them are honesty and humor, and the good capacity to love.

This is the ethos of the young — a commitment not to abstract pieties but to concrete and immediate acts of integrity. It leads to a desire to prove oneself by action and participation — whether in the Peace Corps and VISTA or in the trials of everyday existence. The young prefer performance to platitude. The self-serving rhetoric of our society bores and exasperates them, and those who live by this rhetoric — e.g., their parents — lose their respect.

It is understandably difficult for parents, who have worked hard for their children and their communities, to see themselves as smug and hypocritical. But it is also understandable that the children of the ’60s should have grown sensitive to the gap between what their parents say their values are and what (as the young see it) their values really are. The gap has been made vivid in the way the land of freedom and equality so long and unthinkingly condemned the Negro to tenth-class citizenship. “It is quite right that the young should talk about us as hypocrites,” Judge Charles E. Wyzanski Jr. recently said at Lake Forest College. “We are.”

And more often than they know, parents themselves unconsciously reveal to their children a cynicism about the system or a disgust for it. Every father who bewails the tensions of the competitive, acquisitive life, who says he “lives for the weekend,” who conveys to his children the sense that his life is unfulfilled — they are all, as Prof. Kenneth Keniston of Yale has put it, “unwittingly engaged in social criticism.” Sometimes these frustrated parents find compensation in the rebellion of their young. There is even what one observer has described as the “my son, the revolutionary” reaction of proud parents, like the mother of Mark Rudd, the Columbia student firebrand who emerged in the spring of 1968 as the Che Guevara of Morningside Heights.

Today’s students are not generally mad at their parents. Often they regard their father and mother with a certain compassion as victims of the system that they themselves are determined to resist. In many cases — and this is even true of the militant students — they are only applying the values that their parents affirmed; they are not rebelling against their parents’ attitudes but extending them. Revolt against parents is no longer a big issue. There is so little to revolt against. Seventy-five years ago parents had unquestioning confidence in a set of rather stern values. They knew what was right and what was wrong. Contemporary parents themselves have been swept along too much by the speed-up of modern life to be sure of anything. They may be square, but they are generally too doubtful and diffident to impose their squareness on their children.

Parents today are not so much intrusive as irrelevant. Mike Nichols caught one student’s-eye view of his elders beautifully in The Graduate, with his portrait, so cherished by college students today, of a shy young man freaked out by the surrounding world of towering, braying, pathetic adults. A girl who finished college last June sums it up:

People like their parents as long as their parents do not interfere a whole lot, putting pressure on choice of careers, grades, personal life. … I think freshmen tend to discuss and dislike their parents more than seniors. By then, supposedly, you have some distance on them, and you can afford to be amused or affectionate about them. For instance, if your parents are for Reagan or were for Goldwater, you know the space between you and them on it, and the impossibility of crossing it, so you let them go their imbecilic way and stand back amused. Other people say that they really like their parents. But nobody wants to go back home. For any length of time, it is usually a bad trip.

One student even looks forward to an ultimate “communion of interests” between today’s students and their parents, only “with the younger half having gone through more (which may be necessary in this more complicated, difficult, tense, scary world) to get to the same place.”

No, the boys and girls of the 1960s, unlike the heroes and heroines of Dreiser, Lewis, Fitzgerald and Wolfe, are not targeted against their parents. Their determination is to reject the set of impersonal institutions — the “structures”— which also victimize their parents. And the most convenient “structure” for them to reject is inevitably the college in which they live. In doing so, they construct plausible academic reasons to justify their rejection — classes too large, professors too inaccessible, curricula too rigid, and so on. One wonders, though, whether educational reform is the real reason for student self-assertion, or just a handy one. One sometimes suspects that the fashionable cry against Clark Kerr’s “multiversity” is a pretext, and one doubts whether students today would really prefer to sit on a log with Mark Hopkins.

This does not mean that “student power” is a fake issue. But the students’ object is only incidentally educational reform. Their essential purpose is to show the authorities that they exist as human beings and, through a democratization of the colleges, to increase control of their lives. For one of the oddities about the American system is the fact that American higher education, that extraordinary force for the modernization of society, has never modernized itself. Harold Howe II, the federal Commissioner of Education, has pointed out that “professors who live in the realm of higher education and largely control it are boldly reshaping the world outside the campus gates while neglecting to make corresponding changes to the world within.” Students cannot understand “why university professors who are responsible for the reach into space, for splitting the atom, and for the interpretation of man’s journey on earth seem unable to find the way to make the university pertinent to their lives.”

An “academic revolution” has taken place in recent years; but in some senses it has only made the problem worse. As analyzed by David Riesman and Christopher Jencks in their recent book by that name, it involves the increasing domination of undergraduate education by the methods and values of graduate education. Many professors are more concerned with colleagues than with students, thus increasing the undergraduate longing, in the words of Riesman and Jencks, for “a sense that an adult takes them seriously, and indeed that they have some kind of power over adults which at least partially offsets the power adults obviously have over them.”

Academic government, in most cases, is strictly autocratic. Some colleges still operate according to rules appropriate to the boys’ academies that most of our colleges essentially were in the early 19th century. A Harvard professor, modifying a famous phrase, once described his institution as “a despotism not tempered by the fear of assassination.” As a Columbia student recently put it, “American colleges and universities (with a few exceptions, such as Antioch) are about as democratic as Saudi Arabia.” The students at Columbia, he adds, were “simply fighting for what Americans fought for two centuries ago — the right to govern themselves.”

What does this right imply? At Berkeley students boldly advocated the principle of cogobierno — joint government by students and faculties. This principle has effectively ruined the universities of Latin America, and no sensible person would wish to apply it to the United States. However, many forms of student participation are conceivable short of cogobierno — student membership, for example, on boards of trustees, student control of discipline, housing and other nonacademic matters, student consultation on curriculum and examinations. These student demands may he novel, but they are hardly unreasonable. Yet most college administrations for years have rejected them with about as much consideration as Sukarno, say, would have given to a petition from a crowd of Indonesian peasants.

One can hardly overstate the years of student docility under this traditional and bland academic tyranny. It was only seven years ago that David Riesman, as a professor noting undergraduate complaints about college and society, wrote, “When I ask such students what they have done about these things, they are surprised at the very thought they could do anything. They think I am joking when I suggest that, if things came to the worst, they could picket!” But the careful student generation of the ’50s was already passing away. Soon John F. Kennedy, the civil-rights freedom riders, then the Vietnam war, stirred the campuses into new life. Still college presidents and deans ignored the signs of protest. The result inevitably has been to hand the initiative to student extremists, who seek to prove that force is the only way to make complacent administrators and preoccupied professors listen to legitimate grievances. “Our aim,” as an Oxford student leader put it, “is to completely democratize the University. We shall look for cases on which we can confront authoritarianism in colleges, faculties, and the University.” Or, in the words of Mark Rudd of Columbia: “Our style of politics is to clarify the enemy, to put him up against the wall.”

The present spearhead of undergraduate extremism is that strange organization, or nonorganization, called Students for a Democratic Society. S.D.S. began half a dozen years ago as a rather thoughtful movement of student radicals. Its Port Huron statement of June, 1962, a humane and interesting if interminable document, introduced “participatory democracy” — that is, active individual participation “in those social decisions determining the quality and direction of his life” — as the student’s solution to contemporary perplexities. In these years S.D.S. performed valuable work in combating discrimination and poverty; and this work generated a remarkable feeling of fellowship among those involved. But the Port Huron statement no longer expresses official SDS policy; and SDS itself has become an excellent example of what Lenin, complaining about left-wing Communism in 1919, called “an infantile disorder.”

This is not to suggest that SDS is Communist, even if it contains Maoist and Castroite (or Guevaraite) factions. The basic thrust of SDS is, if anything, syndicalist and anarchistic, though the historical illiteracy of its leadership assures it a most confused and erratic form of anarcho-syndicalism. The anarchistic impulse extends to its organization — the infatuation with decentralization is so great that there is none (the joke is “the Communists can’t take over S.D.S. — they can’t find it”) — as well as to its program. The infatuation with the creative power of immediate action is so great that there is none.

Anarchism, with its unrelenting assault on all forms of authority, is a natural adolescent response to a world of structures. As a French student scribbled on the wall of his university at Nanterre, “L’anarchie, c’est je.” But the danger of anarchism has always been that, lacking rational goals, it moves toward nihilism. The strategy of confrontation turns into a strategy of provocation, intended to drive authority into acts of suppression supposed to reveal the “hidden violence” and true nature of society. Confrontation politics requires both an internal sense of infallibility and an external insistence on discipline. Soon the SDS people began to show themselves, as one student put it to me, “exclusionary, self-righteous, and single-minded. I feel that they, along with certain McCarthy people, are the one group that does not think that everybody should do their thing, but rather do the SDS thing.” In time SDS virtually rejected participatory democracy. Prof. William Appleman Williams of Wisconsin, whose own historical writing stimulated this generation of student radicals, ended by calling them “the most selfish people I know. They just terrify me. … They say, ‘I’m right and you’re wrong and you can’t talk because you’re wrong.’”

In 1967, SDS began to discuss in its workshops how confrontation politics — seizing buildings, taking hostages, and so on — could be used to bring down a great university and selected Columbia as its 1968 target. The result was the uprising last April, which brutal police intervention transformed from an SDS Putsch into a general student insurrection. At Columbia, the SDS leaders displayed no interest in negotiating the ostensible issues. Their interest was power. “If we win,” said Mark Rudd, the SDS leader, “we will take control of your world, your corporation, your university and attempt to mold a world in which we and other people can live as human beings. Your power is directly threatened, since we will have to destroy that power before we can take over.” For the sake of power, they were prepared, as a liberal Columbia professor put it, to “exact a conformity that makes Joe McCarthy look like a civil libertarian.”

As the SDS leaders get increasing kicks out of their revolutionary rhetoric, they have grown mindless, arrogant and, at times, vicious in their treatment of others. In recent months, the young men who incite riot and talk revolution have encouraged acts of exceptional squalor — not only the denial of free speech but the rifling of personal files, the destruction of the research notes of an unpopular professor — in fact, a general commitment not to university reform but to destruction for the sake of destruction. Their influence is to turn students into what John Osborne, one of Britain’s “angry young men” of the ’50s, has called “instant rabble.” Their effect is to betray the function of the university, which is nothing if not a place of unfettered inquiry, and to repudiate the western tradition of intellectual freedom.

What sort of factor will SDS be in the future? No one, including its own national office, can be sure how many members SDS has. J. Edgar Hoover, who is not addicted to minimizing the enemy, told Congress on February 23 that in 1967 SDS had 6,371 members, of whom 875 had paid dues since January 1. Whatever the number, it is an infinitesimal fraction of the American college population. Yet this fact should not induce undue complacency in the country clubs. Many students who would never dream of joining SDS or of approving its tactics nevertheless share its sense of estrangement from American society. This spring the Gallup Poll reported that one student in five had taken part in protest demonstrations — a statistic that suggests not only that a million students may he counted as activists but that the proportion has probably doubled since the estimates of student rebels in the spring of 1966 as 1 in 10 (Samuel Luhell) and 1 in 12 (the Educational Testing Service). All studies, moreover, indicate that the activists are good students and that they abound in the best universities.

What is significant is not only the rather large number of student activists today but their success in winning the tacit consent of the less involved. This does not mean that the majority applauds the gratuitous violence that has swept through many institutions. But activists very often appear to mirror general student concerns and anxieties on a wide range of issues, social and political as well as academic.

A recent episode at Antioch explains why the majority goes along with the activists. Although on other campuses it is considered a paragon of democracy — its students, for example, can attend the meetings of its board of trustees — this fine old experimental college in Yellow Springs, Ohio, evidently still has problems of its own. A year ago the board of trustees met before an audience of some 75 students. One member began to read the report of the committee on the college investments. As he droned along, a student suddenly jumped up and shouted, “This is all a lot of ———“ A second student then arose and said, with elaborate irony, “You shouldn’t talk that way. These wonderful trustees are giving of their time and substance to help us out.” Next, in quick succession, half a dozen other students got up and called caustic single sentences at the startled trustees. At this point, the lights went out. When they came on 30 seconds later, the trustees were confronted by a tableau: one masked student standing with his foot on the chest of another masked student prostrate on the floor. The boy on the floor said, “Massa, is it all right if I use LSD?” The standing student replied, parodying a phrase cherished by academic administrators, “It is all right if you follow institutional processes.” A series of similar Qs and As followed. The lights went out again; there were sounds of scurrying; and, when the lights came on, all but a dozen students had gone.

A moment of silence followed. Then the trustee who had been reading the report from the committee on investments resumed exactly where he had left off. This was too much for a colleague, who broke in and said reasonably, “Mr. Chairman, I don’t think that we ought to act as if nothing had happened.” The chairman asked what he proposed, and the trustee suggested that they invite the students who had remained to tell them what this demonstration had been all about. The students still in the room responded that, while they had not approved of the demonstration, they were now delighted that it had forced the trustees to listen to them. “You may not like what you saw,” one student remarked. “But now you are discussing things that you would never be discussing on your own initiative.” And for the first time the Antioch board of trustees permitted on its agenda some of the problems that were worrying the Antioch students.

This story illustrates a disastrous paradox: The extremist approach works. “I feel like I just wasted three and a half years trying to change this university,” a Columbia senior said after the troubles last spring. “I played the game of rational discourse and persuasion. Now there’s a mood of reconstruction. All the log-jams are broken — violence pays. The tactics of obstruction weren’t right, weren’t justified, but look what happened.” The activists understand what has until recently escaped the attention of the deans — that a small number of undergraduates, if they don’t give a damn, can shut down great and ancient universities. As a result, when the activists turn on, the administrators at last begin to do things which, if they had any sense, they would have done on their own long ago — as Columbia is revising its administrative structure for the first time (The New York Times tells us) since 1810. Commissioner of Education Howe says, “Perhaps students are resorting to unorthodox means because orthodox means are unavailable to them. In any case, they are forcing open new and necessary avenues of communication.” Both Berkeley and Columbia will be wiser and better universities as a result of the student revolts. One can hardly blame the president of the Harvard Crimson for his conclusion:

All the talk in the world about the unacceptability of illegal protest, all the use of police force and all the repressive legislation will not change the fact that attention is drawn to evils in our universities in this way. As long as students have no legitimate democratic voice, attention is drawn only in this way.

The students’ demand for a “legitimate democratic voice” in the decisions that control their future is part of a larger search for control and for meaning in life. The old sources of authority — parents and professors — have lost their potency. Nor does organized religion retain much power either to impose relevant values or to advance the quest for meaning. Nominal affiliation persists, but religious belief in the traditional sense is no longer widespread in college. A Catholic girl recently said that among students she knew, “there definitely is no interest in any doctrine about the supernatural. The interest is in human values.” An eastern sophomore says: “Nobody thinks about religion but probably respect people who have religion because it is so rare.”

As students, finding little sustenance in traditional authorities, seek out values on their own, their search often takes forms that an older generation can only regard as grotesque or perilous. Thus drugs — a device by which, if people cannot find harmony in the world, they can instill harmony in their own consciousness. For many young people, drugs offer the closest thing to a spiritual experience they have; their “trips,” like more conventional forms of mysticism, are excursions in pursuit of transcendental meanings in the cosmos.

The invasion of the life of the young by drugs is relatively recent; and it provides a good illustration of the interesting fact that there is conflict not only between the generations but within the younger generation itself. “When I was a freshman in 1960,” a venerable figure of 25 just out of law school, tells me, “drugs were really a fringe phenomenon. Today pot is the pervasive form of nightly enjoyment for students. How can parents understand this if a person like myself, hardly four years older than my sister, isn’t able to understand it?” His sister, who has just graduated from college, reports, “You see, the people who have been coming in as freshmen since even my first year, ’64, and with a big boom in ’66, have been turned on. Once again, as last year, the biggest pushers are in the freshman class.”

As for the drugs themselves, marijuana is a staple. It causes little discussion in its purchase, use or nonuse. On the large campuses, “everybody” has smoked it at one time or another, or at least this is a common student impression. A more precise estimate — from Dr. Stanley F. Yolles, director of the National Institute of Mental Health — is that “about two million college and high-school students have had some experience with marijuana. Fifty percent of those who have tried it experienced no effects.” Presumably, most of the rest find in the chemical expansion of consciousness an occasional means of relaxation or refreshment — what liquor provides for their parents. It is hard to persuade students (and many doctors) that “grass” is any more lethal than tobacco or alcohol, and parents achieving a high on their fourth martini are advised not to launch a tipsy tirade against marijuana.

LSD, on the other hand, is quite another matter, and its vogue has notably waned in the last year or so. Students, reading about its possible genetic effects and hearing about the “bad trips” of their friends, simply reject it as too risky. College students, it should be added, are very rarely hippies; when drugs begin to define a whole way of life, studies must go by the boards. A few students may now be turning from “acid” to “speed” (Methedrine). But an interesting departure, reported from Cambridge, Mass., is the resurgence of simple, old-fashioned drinking. “Younger kids who really started right off with grass often missed the whole alcoholic thing, and now they stop you on the street and say, wow, they got drunk and what a trip it was.” No doubt this development will reassure troubled parents.

Love is another medium in which the young conduct their search for meaning. Against Vietnam they cried, “Make love, not war.” “The student movement,” one girl observed, “is not a cause. … It is a collision between this one person and that one person. It is a I am going to sit beside you. … Love alone is radical.”

Here attitudes have relaxed, though it is not clear how much the change in sexual attitudes has produced a change in sexual behavior — to some degree, certainly, but not so much as some parents fear. A poll this spring at Oberlin showed that 40 percent of the unmarried women students had (or claimed to have) sexual relations. Dr. Paul Gebhard, who succeeded the late Dr. Alfred Kinsey as director of the Institute for Sex Research at Indiana University, observes that sexual relations among college students are “more fun nowadays,” especially for women, and create less guilt. One girl undergraduate says, “I am convinced there is a greater naturalness and acceptance and much less uptightness about sex in the present college era than in the one earlier.”

Unquestionably the pill has considerably simplified the problem. “No longer is it [again a girl is speaking], oh I can’t sleep with anyone because sex is sinful or risky or whatever; it is rather, do I want to sleep with this person and, if I do, how will it affect me or the relationship. … The emphasis is on satisfying, whole, friendly, honest relationships of which sex is only a part. Where sex is accepted as an extension of things, then nobody really talks about it that much, except as a pleasant thing.”

The new naturalness has encouraged the practice known to deans as “cohabitation” and to students as “shacking up” or “the arrangement” — that is, male and female students living together in off-campus apartments. Rolling with the punch, colleges are now experimenting with coeducational student housing. Nearly half the institutions represented in the Association of College and University Housing Officers now have one form or another of mixed housing. What may be even more shocking to old grads is the vision of the future conveyed by the report that at Stanford the Lambda Nu fraternity proposes next year to go coed.

Though students today favor a code of behavior that is personal, not modeled on that of parents, pastors or professors, they have not abandoned heroes. Nearly all regard John F. Kennedy with admiration and reverence. Many this year followed and then mourned his brother; many others followed Eugene McCarthy (and cut their hair and beards in order to be ‘clean for Gene’); many like John Lindsay. Among writers, the situation is more puzzling. The press reports an enthusiasm on the campuses for J.R.R. Tolkien and The Lord of the Rings; but I must confess sympathy for a perceptive girl who says:

When I stand in lunch lines, I see people holding Tolkien in their hands, but they aren’t the people I know. I guess that people like it because it hands them a whole society and set of symbols and passwords which they can use to describe themselves, set off the cliques. It gives people a whole world of the imagination without having to use their imagination.

The German writer Hermann Hesse with his novels about romantic quests for self-knowledge is having a current whirl — The New Republic reports an electronic-rock group on the west coast calling itself Steppenwolf.

But the testimony is general that the old, whether in public affairs or in literature, don’t count for very much in the colleges. “The models for today’s students,” a sophomore writes, “probably come more from their contemporaries than any other group — the latest draft-card burners, people with the guts to live the way they want despite society’s prohibitions, etc. — or from older people who sympathize with them and give intellectual prestige to their feelings.”

Above all, students find in music and visual images the vehicles that bring home reality. “THE GREAT HEROES OF THIS DAY AND AGE,” a girl affirms in full capitals, “ARE BOB DYLAN AND THE BEATLES.” Dylan “gave us a social conscience and then he gave us folk-rock and open honest talk about drugs and sex and life and memory and past.” One student thinks Dylan “may have a profounder influence than the Beatles because he is American and sings about America — and his evocative powers are profound, to affect those poor people and us. John Wesley Harding is a wandering, obscure, and sad album, but it is also gentle and tender and necessary.”

As for the Beatles, “Well, they taught us how to be happy. We evolved with the Beatles.” The evolution was from a simple happiness to a more complex form of sensibility — from the first, Beatle songs, with their insistent beat, to the intricate electronic songs of today and their witty, ambiguous lyrics.

“When you really listen to Sergeant Pepper, it can be an exhausting, amazing, frightening experience. Especially A Day in the Life, which is a hair-raising song because it is about our futures, too, and death.”

What these heroes stand for, in one way or another, is the affirmation of the private self against the enveloping structures and hypocrisies of organized society. They embody styles of life that the young find desirable and admirable and that they seek for themselves. “Let there be born in us,” the Radcliffe commencement prayer this year concluded, “a strange joy that will help us to live and to die and to remake the soul of our time.”

Yet college students have no easy optimism about the future. “People don’t talk about the future,” says one. “That’s too depressing because it means growing old and having responsibilities and the eventual capitulation to the System, because it won’t change.” “Mostly students know what they don’t want to be,” says another. “They don’t want to be tied down to a hopeless, boring regimen; they don’t want to give in to the Establishment after spending most of their youth avoiding it; they don’t want to profit through special-interest groups and to the detriment of people in need. Mostly, they want to make the society they live in better, richer for all, more fun. The problem is that they lack the plans to accomplish the ends.”

For the moment they are determined, in the words of the student orator at the Notre Dame commencement this year, not to be satisfied to “play the success game.” More college graduates every year embark on careers of public and community service. The acquisitive life of business holds less and less appeal. Yet one can hardly doubt that a good many — perhaps most — of these defiant young people will be absorbed by the System and end living worthy lives as advertising men or insurance salesmen. Hal Draper, an old radical musing on the 800 sit-inners arrested at Berkeley at the height of the Free Speech Movement, wrote, “Ten years from now, most of them will be rising in the world and in income, living in the suburbs from Terra Linda to Atherton, raising two or three babies, voting Democratic, and wondering what on earth they were doing in Sproul Hall — trying to remember, and failing.”

One must hope, for the sake of the country, that some of this fascinating generation do remember — not the angry and senseless things they may have done, but the generous hopes that prompted them to act for a better life. But who can say? Certainly not their elders. Yet the attempt at understanding may even be a useful exercise for the older generation. I discovered this in talking to students for the purposes of this piece. And I treasure a note from one who patiently cooperated. “Even as I distrust anybody of the older generation who tries to write about the younger,” the letter said, “I think it will be interesting to see how you figure it out.”

This article is featured in the July/August 2017 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

The Drug Epidemic That Is Killing Our Children

In the middle-class neighborhood on the east side of Columbus, Ohio, where Myles Schoonover grew up, the kids smoked weed and drank. But while Myles was growing up, he knew no one who did heroin. He and his younger brother, Matt, went to a private Christian high school in a Columbus suburb. Their father, Paul Schoonover, co-owns an insurance agency. Ellen Schoonover, their mother, is a stay-at-home mom and part-time consultant.

Myles partied, but found it easy to bear down and focus. He went off to a Christian university in Tennessee in 2005 and was away from home for most of Matt’s adolescence. Matt had attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and schoolwork came harder to him. He started partying — smoking pot and drinking — about his junior year in high school.

The two brothers got to know each other again when Matt joined Myles at college for his freshman year in 2009. His parents were never sure when exactly Matt began using pills that by then were all over central Ohio and Tennessee. But that year, Myles saw that pills were already a big part of Matt’s life.

Matt hoped school would be a new beginning. It wasn’t. Instead, he accumulated a crew of friends who lacked basic skills and motivation. They slept on Myles’ sofa. Myles ended up cooking for them. For a while he did his brother’s laundry because Matt could wear the same clothes for weeks on end. Matt, at six feet six and burly, was a caring fellow with a soft side. Yet the pills seemed to keep him in a fog.

At year’s end, Matt returned home to live with his parents, where he seemed to have lost the aimlessness he displayed in college. He dressed neatly and worked full-time at catering companies. But by the time he moved home, his parents later realized, he had become a functional addict, using opiate prescription painkillers, and Percocet above all. From there, he moved eventually to OxyContin.

In early 2012, his parents found out. They were worried, but the pills Matt had been abusing were pharmaceuticals prescribed by a doctor. They weren’t some street drug that you could die from, or so they believed. They took him to a doctor, who prescribed a weeklong home detoxification, using blood pressure and sleep medicine to calm the symptoms of opiate withdrawal.

He relapsed a short time later. Unable to afford street OxyContin, Matt at some point switched to the black tar heroin that had saturated the Columbus market. Looking back later, his parents believe this had happened months before they knew of his addiction. But in April 2012, Matt tearfully admitted his heroin problem to his parents. Stunned, they got him into a treatment center.

After three weeks of rehab, Matt came home on May 10, 2012, and with that, his parents felt the nightmare was over. The next day, they bought him a new battery for his car and a new cellphone.

He set off to a Narcotics Anonymous meeting, then a golf date with friends. He was supposed to call his father after the NA meeting.

His parents waited all day for the call. That night, a policeman knocked on their door.

More than 800 people attended Matt’s funeral. He was 21 when he overdosed on black tar heroin.

In the months after Matt died, Paul and Ellen Schoonover were struck by all they didn’t know. First, the pills: Doctors prescribed them, so how could they lead to heroin and death? People who lived in tents under overpasses used heroin. Matt grew up in the best neighborhoods, attended a Christian private school and a prominent church. He’d admitted his addiction, sought help, and received the best residential drug treatment in Columbus. Why wasn’t that enough?

But across America, thousands of people like Matt Schoonover were dying. Auto fatalities had been the leading cause of accidental death for decades until this. Now most of the fatal overdoses were from opiates: prescription painkillers or heroin. If deaths were the measurement, this wave of opiate abuse was the worst drug scourge to ever hit the country.

This epidemic involved more users and far more death than the crack plague of the 1990s or the heroin plague in the 1970s, but it was happening quietly. Kids were dying in the Rust Belt of Ohio and the Bible Belt of Tennessee. Some of the worst of it was in Charlotte’s best country club enclaves. It was in Mission Viejo and Simi Valley in suburban Southern California, and in Indianapolis, Salt Lake, and Albuquerque, in Oregon and Minnesota and Oklahoma and Alabama. For each of the thousands who died every year, many hundreds more were addicted.

Via pills, heroin had entered the mainstream. The new addicts were football players and cheerleaders; football was almost a gateway to opiate addiction. Wounded soldiers returned from Afghanistan hooked on pain pills and died in America. Kids got hooked in college and died there. Some of these addicts were from rough corners of rural Appalachia. But many more were from the U.S. middle class. They lived in communities where the driveways were clean, the cars were new, and the shopping centers attracted congregations of Starbucks, Home Depot, CVS, and Applebee’s. They were the daughters of preachers, the sons of cops and doctors, the children of contractors and teachers and business owners and bankers.

And almost every one was white.

Children of the most privileged group in the wealthiest country in the history of the world were getting hooked and dying in almost epidemic numbers from substances meant to, of all things, numb pain. “What pain?” a South Carolina cop asked rhetorically one afternoon as we toured the fine neighborhoods south of Charlotte, where he arrested kids for pills and heroin.

Crime was at historic lows, drug overdose deaths at record highs. A happy façade covered a disturbing reality. “We’ve never seen anything move this fast,” Ed Hughes, at the Drug Counseling Center in Portsmouth, Ohio, told me. Silence, he thought, was a huge part of the story.

Kids were coming to the center from across Ohio. Many, he said, grew up coddled, bored, and unprepared for life’s hazards and difficulties. They’d grown up amid the consumerist boom that began in the mid-1990s. Parenting was changing then, too, Hughes believed. “Spoiled rich kid” syndrome seeped into America’s middle classes. Parents shielded their kids from complications and hardships and praised them for minor accomplishments — all as they had less time for their kids.

“You only develop self-esteem one way, and that’s through accomplishment,” Hughes said. “You have a lot of kids who have everything and look good, but they don’t have any self-esteem. You see 20-somethings: They have a nice car, money in their pocket, and they got a cellphone … a big-screen TV. I ask them, ‘Where the hell did all that stuff come from? You’re a student.’ ‘My mom and dad gave it to me.’ … And you put opiate addiction in the middle of that?”

Hughes knew families as addicted to rescuing their children as their kids were addicted to dope. This, too, was an epidemic, Hughes believed. “I’ve got 40-year-olds who act like 22-year-olds because their families are so enmeshed in rescuing them. The parents are giving them a place to live, giving them money, taking care of things, worrying about them, and calling me trying to get them into treatment. I try to tell parents it’s real important to say no, but say no way back when they’re young.”

Most of these parents were products, as I am, of the 1970s, when heroin was considered the most vile back-alley drug. How could they now tell their neighbors that the child to whom they had given everything was a prostitute who expired while shooting up in a car outside a Burger King? Shamed and horrified by the stigma, many could not, and did not.

Opiate use in medicine had been destigmatized by doctors who crusaded against pain. But there were no prestigious crusaders against the addiction that too often resulted from overuse of these pills. That task fell to parents of dead kids, like Wayne Campbell, a barrel-chested guy with the personality of the football coach he was part-time.

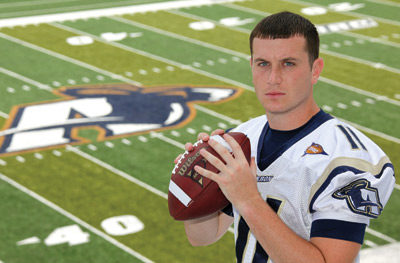

Wayne’s oldest son, Tyler, had played football. He was a safety for the Division I University of Akron Zips. In 2009, the school opened a 30,000-seat football stadium, a monument to corporate America in sports. If ever the Division I school needed a good year from its team, 2009 was it.

Instead, the team disintegrated under the pressure to win and the weight of pills.

(John Kuntz/The Plain Dealer)

The Zips’ star quarterback that year, Chris Jacquemain, grew addicted to OxyContin after suffering a separated shoulder. He began stealing and was expelled from the team early in the season, then left school. Jacquemain’s life spiraled down. He died of a heroin overdose two years later.

Something like that happened to Wayne’s son, Tyler. A walk-on and an eager and aggressive safety, Tyler Campbell was prescribed 60 Percocets after shoulder surgery following the 2008 season. He was given no instructions about the drug and how to use it. Nor was it clear that he needed that many pills to recover from the surgery. Doctors told Wayne it was the usual postsurgical prescription. It seemed to Wayne that doctors wanted to make sure patients didn’t return quickly, so they prescribed a lot. That was part of the problem, he figured.

Wayne spoke later with Jeremy Bruce, a wide receiver on the team, who provided a glimpse of the team unraveling that year. The coaches and trainers, Bruce said, felt pressured to field a winning team as the school opened its new stadium. After the games, some of the trainers pulled out a large jar and handed out oxycodone and hydrocodone pills — as many as a dozen to each player. Later in the week, a doctor would write players prescriptions for opiate painkillers and send student aides to the pharmacy to fill them. “I was on pain pills that whole season — hydrocodone or oxycodone. I was given narcotics after every single game, and it wasn’t recorded. It was like they were handing out candy,” Bruce told me.

One problem the team faced was a steep drop-off in talent from the first to the second string, Bruce said. As first-stringers got hurt and second-stringers couldn’t fill in, he said, “it’s a snowball effect because of the pressure and the stress just to get those [first-stringers] back on the field. I think that’s where the narcotics came into play, and that’s why it was handed out so easily — the stress and the pressure to win right now.”

J.D. Brookhart, the team’s head coach that year, said that he knew nothing of the extent of opiate dependence on the team that Bruce describes. “That wasn’t the case, that we knew of,” he said. “I don’t think it was anything that anybody thought was anything rampant at all. Not from the level I was at. It’s not like trainers or coaches had any authorization [to prescribe pills]. These pills were ordered by doctors.”

Injuries were the team’s overriding issue that season, Brookhart told me from his home in Texas, where he has retired from coaching. Some 24 players missed eight or more games apiece due to injuries that year; this included two of Jacquemain’s three backups, he said.

By the end of the 2009 season, the Akron Zips football team was a poster squad for America’s opiate epidemic. Not only was Jacquemain dismissed for issues related to his addiction, but as the season wore on and the injuries mounted, Bruce said, “I would say 15 to 17 kids had a problem. It seems that most who had an addiction problem had an extensive problem with injuries as well.”

Toward the end of the season, he said, players had learned to hit up teammates who had just had surgery, knowing they would have bottles full of pills. Meanwhile, a dealer from off campus sold to the players, visiting before practice sometimes, fronting players pills and being paid from the monthly rent and food allowance that came with their scholarships.

The Zips inaugurated the new stadium with only three wins. The coaching staff would be fired at season’s end, but the effect of the season lingered on.

Among the team’s weaknesses was the size of its defensive line. The problem was felt acutely at Tyler Campbell’s position, safety. Running backs often broke through the defensive line and linebackers. It too often fell to safeties to make tackles. Against a monstrous Wisconsin team, the first game of the 2008 season, with a scholarship now and starting his first collegiate game, Tyler for one week was the nation’s leader in tackles, with 18 — an exploit that coaches attributed to his hard work and perseverance.

His stats, though, highlighted the team’s weakness. When a safety is making that many tackles, Bruce said, “there is a serious problem. [Opposing running backs] should never get to the secondary that many times.”

As the season went on, Tyler injured his shoulder. His body never fully healed, and he had surgery after the season. Team doctors could give Wayne no records of what Tyler was given after games. But those first 60 post-surgery Percocets following the 2008 season seem to have begun his addiction. By the next season, unbeknownst to those close to him, Tyler had transitioned to OxyContin.

Tyler’s 2009 season was spotty. He played 11 games but made only 31 tackles, and grew secretive and distant, which teammates and family attributed to his play on the field. In the spring of 2010, his grades dropping and his behavior moody, Tyler was sent home. Over the next year, he was in rehab twice and relapsed. At some point, he switched to heroin.

In June 2011, his parents put him in an expensive rehab center in Cleveland. Thirty days later, he drove home with his mother, clean, optimistic, and wanting to become a counselor. The next morning, she found him dead in his bedroom of an overdose of black tar heroin from Columbus — likely hidden in his room from before he entered rehab, Wayne believes.

With a solid reputation in Pickerington, Tyler’s family had kept his addiction a secret. But when he died, Wayne told his wife, “Let’s open it up. Come out and be honest.”

The obituary urged mourners to donate money to a drug prevention group. Fifteen hundred people attended the memorial. As they consoled him, Wayne was struck by how many murmured in his ear, “We’ve got the same problem at home.”

Two weeks later, Wayne met with fathers who wanted to do something in his son’s memory. He knew few of them, but learned that several also had addicted kids. That marked a moment of clarity for Wayne Campbell. “When Tyler died, it lifted the lid,” he said. “We thought it was our dirty little secret. I thought he was the only one. Then I realized this is bigger than Tyler.”

From that grew a nonprofit called Tyler’s Light. By the time I met Wayne Campbell, Tyler’s Light had become his life’s work. He spoke regularly to schools about opiates, showing a video of white middle-class addicts, one of whom was a judge’s daughter.

About a year after Wayne Campbell formed Tyler’s Light, Paul Schoonover called. Could he and his wife, Ellen, help in any way? Schoonover asked. It had been a few months since Matt had died.

At Matt’s funeral, Paul had told hundreds of mourners how Matt had died. About the pill use, the OxyContin, then the heroin. He told them how through all this, Matt led a normal suburban life; he played tennis and golf. Most of his friends were goal driven and making plans. Matt had goals, but had trouble following through to accomplish them. Still, he was working and part of the family. He never dressed shabbily, and though he ran out of cash quickly, he never stole from his parents. His bedroom door was always open. He never looked like what his parents imagined an addict to be. Yet all the while, it appeared, he led a dual life.

“Was I seeing what I only wanted to see?” said Ellen later. “I might have been.”

(Craig Holman/The Columbus Dispatch)

The Schoonovers, like the Campbells, once thought addiction a moral failing. But they now understood it as a physical addiction, a disease. They, too, had thought rehabilitation would fix their son. Now they saw relapse was all but inevitable, and that something like two years of treatment and abstinence, followed by a lifetime of 12-step meetings, were needed for recovery.

After kicking opiates, “it takes two years for your dopamine receptors to start working naturally,” Paul said. “Nobody told us that. We thought he was fixed because he was coming out of rehab. Kids aren’t fixed. It takes years of clean living to the point where they may — they may — have a chance. This is a lifelong battle. Had we known, we would never have let Matt alone those first few vulnerable days after rehab. We let him go alone that afternoon to Narcotics Anonymous his first day out of rehab. He had his new clothes on. He looked good. He was then going to play golf with his friend. Instead of making a right turn to go to the meeting, he made a left turn and he’s buying drugs and dying.

“When you start into drugs, your emotional development gets stunted. Matt was 21, but he was at the maturity level of middle-teen years. Drugs take away that ability to act emotionally mature. The drug becomes your god.”

The Schoonovers choose to channel their grief into getting the word out. Too many parents were as lost as they’d been.

So Paul called Wayne Campbell and Tyler’s Light, hoping to use Matt’s story to sound the alarm and prepare parents for what awaited them.

“There was so much evil in all of this,” said Ellen Schoonover. “We will turn that into something good. We can embrace it and find meaning from Matt’s death.”

The Cans That Saved Choir

(Photo courtesy Shutterstock)

Cling … Clang … Clank. From inside my apartment, I winced at the noise my parents were making as they sorted bottles and cans out on the cramped balcony. With as much enthusiasm as I could muster, I called to my mother in Chinese, “How many do you have this time?”

“Eight hundred and six pieces, that’s $40.30!” she answered. “That makes it $309.55 in total — a decent month’s salary back home!”

I’d been living in my West Los Angeles apartment for a little over four years when my parents came for a six-month visit from the town in northeastern China where I grew up. Just a few weeks into their stay, my mother had appointed herself CFO of recycling. I’d casually mentioned that the plastic water bottle and aluminum can they’d noticed on the curb were worth 5 cents each. I had no idea that simple revelation would open such a can of worms —“golden” worms as far as my parents were concerned.

For the next several months, my building endured the clutter and clamor of my parents’ enthusiastic recycling. At dinnertime, Mom and Dad took turns recounting a list of perfectly usable things they had seen being thrown out that day. When their stay with us ended, I must confess that I felt free and relieved (and then guilty). I suspect my neighbors noticed their absence immediately. My balcony reverted to its role as a tiny garden.

Little did I know, though, that only a few months later I would be cluttering that balcony right up again and informing my parents that they had inspired me to start a recycling fundraiser at my daughter’s school. I named it the Green for Green program. To date it has brought in — bottle by bottle, can by can — more than $15,000.

When I was growing up in China, parental involvement at school was limited to attending parent-teacher conferences to discuss academic issues. Schools were free but with very limited resources (no library, gym, or science labs) and huge class sizes: up to 60 students. Students helped clean and make simple repairs. Schools operated within their means, and fundraising didn’t exist.

By the time I had a daughter of my own and she began school, I had lived in America for six years and become an American citizen. Although I considered myself pretty well assimilated, I was confused and skeptical when I first heard that I was expected to raise funds for the school. If American public schools are free, how come they keep asking for money? While fundraising for public school was a foreign concept to me, recycling was not. Wastefulness (langfei in Chinese) has been considered a vice since the earliest Chinese cultures. My parents, like most Chinese people of their generation, use everything to death, beyond the point of any possible salvage, and then they still save it just in case. Reduce, Reuse, and Recycle was a principle of survival. One of the first children’s rhymes I learned was, “Every grain of rice represents a drop of farmer’s sweat.”

During years of strict rationing in the 1970s, my mom even saved her shoelaces, unraveling them into yarn to knit mittens for me. Many of my clothes were altered hand-me-downs from my mom, aunts, and grandmother. Every scrap of cloth was used as a patch, a doll’s dress, or a rag. Dogs and cats ate people’s leftovers, and restaurants raised pigs in the backyard to feed on customers’ leftovers. When a junk collector came through the neighborhood with a wheelbarrow, chanting “Shou po lan!” (“Junk collection!”), my neighbors would chase him down with saved-up cardboard, paper, glass, metal — and sometimes even hair — to exchange for money. We went to the market with our own baskets and carried our grains and flour home in cloth bags made from used bedsheets.

When I first arrived in the U.S., I was amazed by garage sales and what they suggested: waves of new purchases rolling in, and waves of old purchases, now unwanted clutter, rolling out. Although many conscientious Americans make an effort to recycle at home, I have seen little public infrastructure set up here to make it as easy as consuming and wasting — not even, to my astonishment, in schools. We sometimes seem to be too wealthy for our own good.

But economic setbacks hit us too. During the recent economic recession, my daughter’s school, the Los Angeles Center for Enriched Studies (LACES), lost hundreds of thousands of dollars in state and federal support, including $300,000 in Title I funding (earmarked to help schools with a large percentage of students from low-income families).

I felt heavy pressure to help raise funds for my daughter’s school. At the same time, I have long felt strongly about environmental education. How could I get the whole community excited about “Reduce, Reuse, Recycle” during such a stressful and cash-strapped time? That’s when it hit me: how about uniting the two? LACES has more than 1,600 students, teachers, and staff. If my two elderly parents could raise $300 in six months from recycling, why couldn’t our school multiply that number by at least 800?