It’s the City Versus the Car, and This Is Your Referee

The spirit of free-range motoring was already coming to an end in America when, on July 16, 1935, the nation’s first parking meter was installed.

The “coin controlled parking meter,” invented by Carl Magee, was not intended to squeeze money out of hapless drivers, but to make parking more equitable. Until that fateful day in July, motorists were limited only by an honor system that requested they not exceed the posted limits for parking.

Without anyone watching when cars arrived, though, motorists could occupy a parking space indefinitely. The choice spaces directly outside stores were filled all day by early arriving office workers.

So the first meters were installed and, for a short time, were appreciated for their practicality and novelty. After all, the meter helped ensure Americans had a chance, however slim, of parking directly in front of their destination.

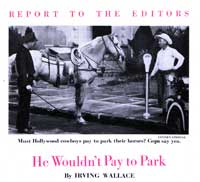

The parking meter didn’t appear without opposition, though. A May 19, 1951, article by novelist Irving Wallace described one man’s response to the meters and his ultimate victory.

“Somewhere in the United States a motorist is likely to christen the country’s millionth parking meter this year simply by dropping in a coin. The meters, which first appeared in 1935 as a novelty invented by an Oklahoma lawyer, have gone up lately at the rate of 150,000 a year.”

According to Robert Luttrell’s Web site, there were five million parking meters in the United States in 2001. “Based on this number, if every parking meter collected only 25 cents per day, the gross revenues generated by parking meters in the United States for one day would be a staggering 1.25 million dollars.”

Click image to download PDF

The Post article reported, “They are now a familiar feature of 2500 communities, including four fifths of the sizable cities and some revenue-hungry small towns. Their total take this year is expected to exceed $50,000,000 in nickels and pennies from motorists in forty-seven states—but not in North Dakota. There, contrary to the trend, they have been outlawed through the efforts of one embattled farmer.

“What Farmer Howard Henry fired was not the shot heard round the world, but a polite response to a rookie cop on a quiet Minot street. ‘I was just coming to put another nickel in the meter,’ Henry said. ‘Too late,’ the cop replied, handing him a ticket.

“Summoned to court, Henry lectured the local judge. ‘My parents traded in this town in horse-and-buggy days. I’ve traded here since I was old enough to farm. I can recall when the towns were so hard up and wanted our trade so badly that they put on free movies. Now, if we don’t pay to park, they haul us into court like criminals. It isn’t American. I’m one farmer who isn’t going to pay to park in a state with as much space as North Dakota.’

“When the judge fined him a dollar, Henry paid, went to the nearest telephone and canceled all his spring orders with Minot merchants. Then he canvassed the state for support. But municipal officials told him he was old-fashioned, that parking meters were as much a part of streets as fire hydrants. Newspapers which had praised his nationally recognized achievements in growing potatoes and wheat now poked fun at him. ‘It was after I was sneered at in Minot, a city of 22,000 that took $40,000 from parking meters in a year, and was politely ignored in Grand Forks, Fargo, and Bismarck that I decided to take the issue to the voters of the state,’ Henry says. He got enough signatures to place the question of outlawing meters before the voters in the 1948 primary. By a margin of only 2522, they voted a ban automatically into effect.

“City leaders, confronted with a revenue loss, waged a campaign to repeal the ban in the November general election. Henry was running meanwhile as the Democratic candidate for governor. The state voted straight Republican—but kept Henry’s parking-meter ban in effect by a walloping 22,744 votes.

“Nowadays, Henry, who owns 3680 choice acres, doesn’t have to worry about parking meters even when he goes as far away as Texas, for he flies in his own plane.

“But the meter controversy continues full tilt. It took on an aspect of hand-to-hand combat in Nebraska, where an irate citizen was nabbed after uprooting a meter. He said it owed him money and, being unable to crack it open, he was taking it home to demolish it at his leisure.

“In Maine an unsteady pedestrian, looking for something to steady himself and seeing no lampposts, conscientiously deposited a nickel in a parking meter and clung to the meter for support. When police tried to detach him, he protested that he still had twenty-five minutes left.”

Any driver in a major city knows the frustrations of parking. There never seems to be enough, and it always costs more than we expect. In cities like New York, it has remained a chronic problem. But New York’s crowded, narrow streets discouraged all but the most adventurous drivers. Chicago, on the other hand, built broad, inviting avenues to accommodate crowds of traffic.

Consequently, many Chicagoans held onto their cars, even when they became too numerous for the city to handle. The city has responded by installing more parking meters. Free parking has all but disappeared and parking fines have risen sharply. For all the discouragement, though, the number of automobiles in Chicago continues to grow.

Meanwhile, out on the prairies of North Dakota, the parking meter is still outlawed.