America’s First Museum: Charles Willson Peale’s “Novel Idea That Stuck”

What does it take to create a museum from scratch, particularly when it hasn’t been done before? As the colonies of the New World united to prepare for war against England, Charles Willson Peale established America’s first successful public museum in Philadelphia, in addition to being an artist, soldier, and naturalist.

“Peale was both a self-promoter and a deeply curious person, so he was always eager to see what he could learn from others,” says Merrill Mason, director at American Philosophical Society (APS), which exhibited “Curious Revolutionaries: The Peales of Philadelphia” at the APS Museum in Philadelphia last year.

Peale became a saddle maker’s apprentice early on in life, but he realized fairly quickly he needed to make more money and gain greater public recognition. “While a saddle maker’s apprentice, he also did other odd jobs — including sign painting,” Mason says. “He was skilled at this, and likely thought if he took some lessons, he could make more money doing portraits.” Acting on this hunch, he traded a saddle for a few painting lessons.

Eventually, Peale acquired a small following among prominent Marylanders, who funded Peale’s trip to London in 1767. It was on this trip that he met Benjamin Franklin. “When in London, Peale called upon Benjamin Franklin without an introduction,” Mason says. “Peale’s sketchbook includes a light pencil drawing of Franklin with a young lady in his lap, a scene that he claimed to have observed while waiting to meet with Franklin.”

After returning to the American colonies in 1769, Peale created a studio in Annapolis, MD. He then began traveling around the eastern shore of Maryland and to Baltimore and Virginia, where he gained a following for his portraits.

His involvement in revolutionary politics progressed after moving his family to Philadelphia. “He enlisted in the continental army when the Revolutionary War broke out, fighting in the battles of Trenton and Princeton with his brother James,” Mason says.

Well-liked among officers, Peale rose to the captain rank in the Pennsylvania militia. Mason says, “Peale’s involvement with politics and the revolution put him in contact with many of the leaders of the revolution, and his portraits of them would be the thing to gain him recognition as a key artistic and political figure.”

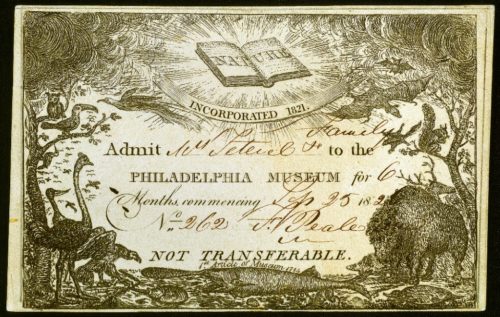

Near the war’s official end, in 1782 — just a year or so before both sides signed the Treaty of Paris — he opened a portrait gallery in his home studio. He displayed his portraits of George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, and Alexander Hamilton. It’s here where he opened the first public museum — called the Philadelphia Museum — in 1786.

“We say the Philadelphia Museum was the nation’s ‘first successful public museum,’” she says. “The Charleston Museum predates the Philadelphia Museum (opened in 1773), but did not open to the public until 1824. The Swiss artist Pierre Eugene Du Simitiere opened a public natural history museum in Philadelphia in 1782, but the collection was sold soon after his death in 1784, so it did not make the same impact as the Philadelphia Museum.”

Nearly 10 years later, in 1794, the Philadelphia Museum moved to The American Philosophical Society, a scholarly organization founded by Benjamin Franklin and others.

Peale’s museum was much more than a portrait gallery. As a follower of The Enlightenment, he believed there was much to be learned from the natural world. In 1801, on a trip funded by APS, he excavated two mastodons in upstate New York (he memorialized the scene some years later in a painting called The Exhumation of the Mastodon). Mason calls it his “most famous contribution to science and the fledgling field of paleontology.” Peale, his son Rembrandt, and Moses Williams, a Peale family slave at the time, reconstructed the fossilized mastodon. On Christmas Eve in 1801, the Peale family unveiled the completed project in APS’ Philosophical Hall.

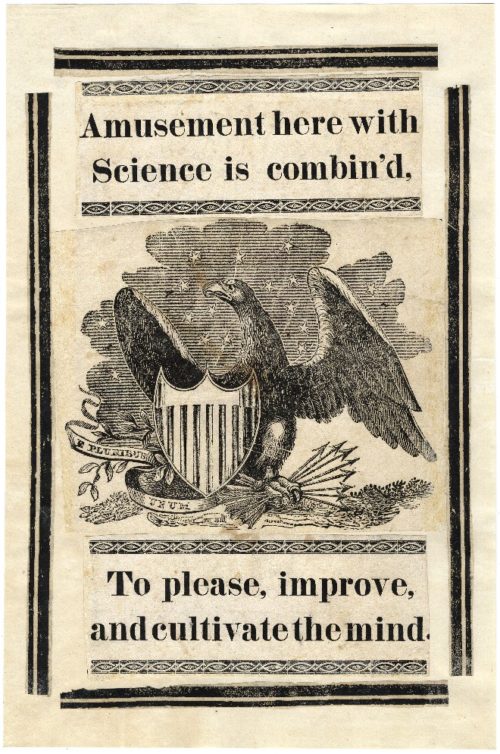

“Charles Willson had established not only America’s first successful public museum, but its first natural history museum,” Mason says. “More than accumulated oddities, Peale’s collections were ordered, classified and labeled according to scientific principles. His ‘Wonderful Works of Nature’ were ‘classed and arranged’ by species, according to Linnaean principles of taxonomic order, for ‘greater ease to the Curious.’”

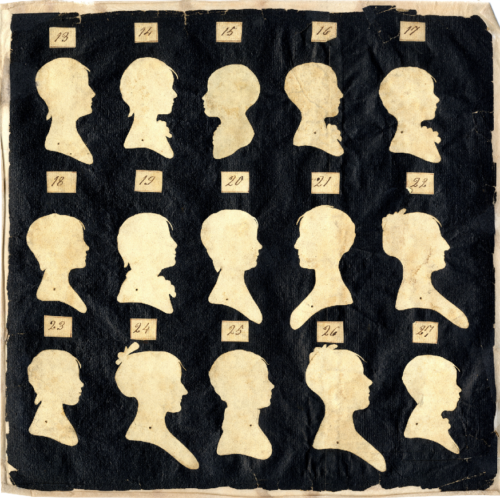

The following year, both Philosophical Hall and the Pennsylvania State House (now Independence Hall) housed the museum’s galleries. “Silhouettes were a popular souvenir at the Philadelphia Museum,” Mason says. “They used a physiognotrace — a device that traces the sitter’s profile and shrinks it down to miniature size. The tracing is then cut out of white paper and the outline attached to a black background.” Williams became known for his silhouettes after the Peale family trained him on the instruments.

The museum eventually transitioned to the State House entirely by 1810. Over the next few decades, the museum continued to exhibit natural history collections — many of which were either bought by the Peale family or donated to the museum.

“The first donation — a preserved paddlefish — came from APS President Robert Patterson, who served on the Philadelphia Museum’s board of visitors,” Mason says. “Bird specimens were brought back from the Lewis and Clark Expedition, which was partially funded by the APS.”

A jack of all trades, Peale had a fascination with technological advancement. Throughout his life, he tinkered with this and that; his family shared his enthusiasm. For instance, they patented efficient stoves, improved bicycle prototypes and even tested false teeth.

“At the museum, they introduced ceiling fans and gas lamps,” she says. “In their artistic and scientific pursuits, they used the camera lucida, experimented with pigments, and advanced the use of photography. Above all, the Peales embraced the Enlightenment ideal to expand man’s universal knowledge while improving life on earth.”

The museum remained at the State House until 1827, the year of Peale’s death. Afterward, his sons moved the museum to another location nearby. Despite their best efforts, Peale’s children were unable to sustain the museum.

“Peale’s Museum and all of its collections were sold at auction between 1848 and 1854,” Mason says. “Many of the paintings were purchased by the city of Philadelphia, and today can be seen in the Second Bank building as part of Independence National Historic Park. The bulk of the natural and cultural collections were lost to catastrophic fires after they were sold to P.T. Barnum.”

The surviving natural collections are some of the earliest in the United States. Museums at Harvard, Philadelphia’s Academy of Natural Sciences, and APS have preserved a few of the remnants (some of which are reference specimens).

“Peale’s Museum was a novel idea that stuck,” Mason says. “As a repository of significant artworks, natural objects, and cultural artifacts aimed at amusing and educating the broad public, the Philadelphia Museum set the precedent for modern museums. Peale’s innovations such as tiered ticketing, yearly membership, advisory boards, and targeted programming are all recognizable in today’s museums. The legacy of Peale’s democratic museum lives on, embedded in the museums we visit today.”