Peggy Lee’s Pursuit of Positivity

Writing about the irrepressible Peggy Lee in this magazine in 1964, Thomas C. Wheeler described one of the jazz singer’s recent performances of her song “Great Big Love”: “Singing about the sun lighting up the world, she spins around the stage spreading her arms like a blonde astronaut weightless in a capsule. The goggle-eyed audiences look as if they are watching the first lady to be orbited.”

At the time, Lee’s career was unprecedented. She had sold more than 20 million records in her two decades of recording music, and she attracted a large fanbase that was diverse in every possible way. Today, she would be 100 years old.

In spite of her hard work and good fortune, Peggy Lee was often plagued with profound unhappiness that sent her on a spiritual quest for inner peace.

After being discovered by Benny Goodman in the ’40s, “Miss Peggy Lee” sold her sultry jazz persona with hits like “Somebody Else Is Taking My Place,” “Why Don’t You Do Right?,” and “Fever.” She cut records at breakneck speed, arranging jazz standards and pop songs along with her own work. She starred in The Lady and the Tramp, a remake of The Jazz Singer, and Pete Kelly’s Blues, earning an Oscar nomination.

Although Lee’s music career had been a remarkable success — affording her a peach-interior mansion in Bel Air — the sensual singer struggled with a traumatic childhood and rocky relationships. In 1969, she released the song that would come to embody her career, the one in which she asked “Is That All There Is?”

The song tells about a young girl who sees “the whole world go up in flames” when her house catches fire, an experience Lee had been through herself. She had also lost her mother at a young age. When Peggy Lee went searching for answers to her life’s tragic questions, she went to Ernest Holmes and The Science of Mind.

Holmes was a leader in the metaphysical Religious Science movement. He encouraged its adherents to use positive intentions in order to conjure happiness. Holmes’s 1926 book, The Science of Mind, was a hit with other Hollywood luminaries too, like Cecil B. DeMille and Cary Grant. Lee became close with Holmes, consulting him often and even coming to affectionately call him “Papa,” according to James Gavin’s biography Is That All There Is? The Strange Life of Peggy Lee.

As Holmes wrote in the credo of his church, “We believe in the direct revelation of truth through our intuitive and spiritual nature, and that anyone may become a revealer of truth who lives in close contact with the indwelling God.” Gavin explains the appeal of Holmes’s hybrid religion: “For Lee, who already lived by the force of her imagination, Holmes’s edicts seemed heaven-sent, the confirmation of all she wished to believe.” She had been “looking for God” since her mother died when she was four years old.

Peggy Lee singing “Is That All There Is?” in 1969. (Uploaded to YouTube by Peggy Lee / Universal Music Group)

Gavin’s biography paints a less-than-charitable picture of Peggy Lee, exposing her as a woman who was, “by all accounts, an alcoholic, a prescription-drug addict, a heavy smoker and a binge eater frequently out of touch with reality.” But no one could ever say she didn’t put in the work, or that she didn’t at least try to improve herself. In her conversation with Wheeler for the Post in 1964, Lee described her approach to spirituality and self-improvement, specifically recalling an evening with composer Cy Coleman in New York in which she guided him through a calming meditation, repeating the phrase “receiving and giving” to him over and over. “That’s what we have to do, all the time. Receiving and giving,” she said.

Her anthem “Is That All There Is?” might seem — on its face — to be a lamentation to “break out the booze and have a ball” in light of life’s disappointments, but she didn’t wish for it to be interpreted that way (at least, according to an interview she gave with Science of Mind magazine in 1987). Lee said that the title and chorus had a different meaning for her. She had moved the emphasis of the chorus from that to is to try to make the song into a hopeful affirmation: “To me, it was just the opposite. It said we go through one experience after another, some of them negative into a positive. We learn, grow stronger, can go on to new experiences because there is always more.”

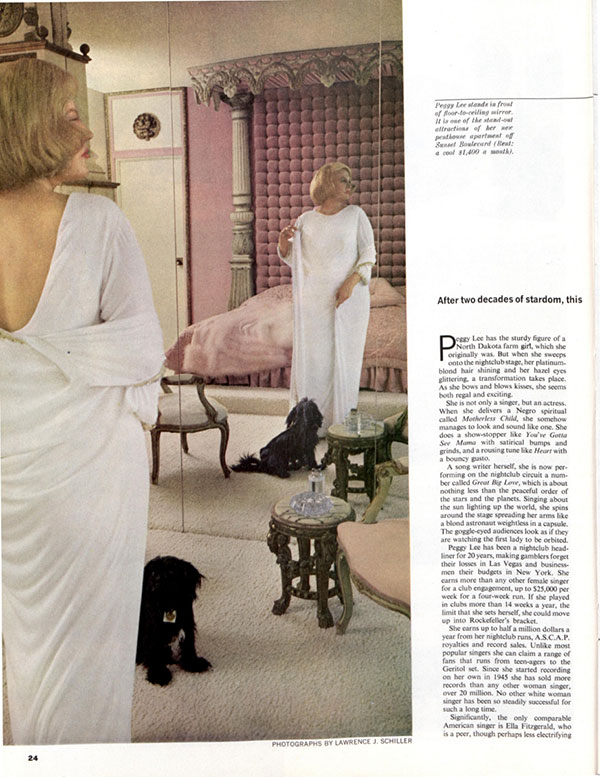

Featured Image: Peggy Lee (Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain)