North Country Girl: Chapter 67 — The Best Job in the World

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir.

Some names have been changed.

As editorial assistant at Penthouse magazine, my duties were editing the vile Letters section, a daily dose of saltpeter to my own sex life (a task I finally ditched on someone else), and taking my boss out to three-martini lunches (slugging back a few glasses of life-and-sanity-saving white wine myself).

Now that I was sprung from my smutty epistolary prison, the question was what I would do for those six hours a day I was not at lunch.

I was sent off to talk to Paul Bresnick, who had the competing titles of fiction and service editor.

Paul had literary taste of the first water backed by the deep pockets of Penthouse, which let him purchase stories and book excerpts by Gore Vidal, Philip Roth, James Baldwin, Paul Theroux, and other high flyers.

By rights a fiction editor who worked with five-star authors should be above dealing with humdrum service articles. Service supposedly meant consumer services, as if we were doing the readers a favor by running reviews of cars, motorcycles, electronics, and cameras. In reality the service we provided was for the advertisers, plugging their products in glowing terms. It didn’t matter if what you produced was a lemon; purchase a full-page ad in Penthouse and your Isuzu or Yugo would be written about and photographed as lovingly as if it were a Pet of the Month.

Paul was as eager to dump his unwanted editorial task as I had been.

“I’m flying to London tomorrow to meet with J.P. Donleavy and I’m stuck editing an article on radar detectors,” he groused.

My short stint at Viva had been all about coming up with punning headlines and appeasing advertisers. I was the woman for the job of service editor. I just couldn’t believe Paul would willingly give up such a plum, especially to someone who could barely drive a car, had no idea how a stereo worked, and had trouble focusing a camera. Despite my shortcomings, I was bequeathed the lofty title of service editor of Penthouse magazine, the best job in the world.

My favorite perks of this new gig were free meals at lavish press parties, thrown by PR agencies that seemed to be wallowing in money. In 1980 it was après moi le deluge for the automotive industry; a company couldn’t bring out as much as a new spark plug without a press conference, always held at a suitably masculine restaurant with plenty to eat and drink to sweeten their spiel.

A short-lived competitor to STP took over the top floor of the 21 Club to hype their doomed product to the car press, which was 99.9% male and then me. In between the mountainous wedge of iceberg lettuce topped with a glacier of blue cheese dressing and the Flintstone-sized T-bone, we were served a palate-cleansing consommé. The already drunken Car & Driver editor next to me nudged me in the side with his elbow and asked “Is your soup empty too?”

There were also invitations to test drive cars, sometimes at day-long events out of the city and sometimes really out of the city, at bashes thrown at the Greenbrier or in Palm Desert, all expenses paid. These invitations I was required to turn over to my boss, Jim Goode, the executive editor. I didn’t mind; I knew that if I were plopped behind the wheel of a souped-up car with a helmet smashed on my head I would immediately drive into a ditch.

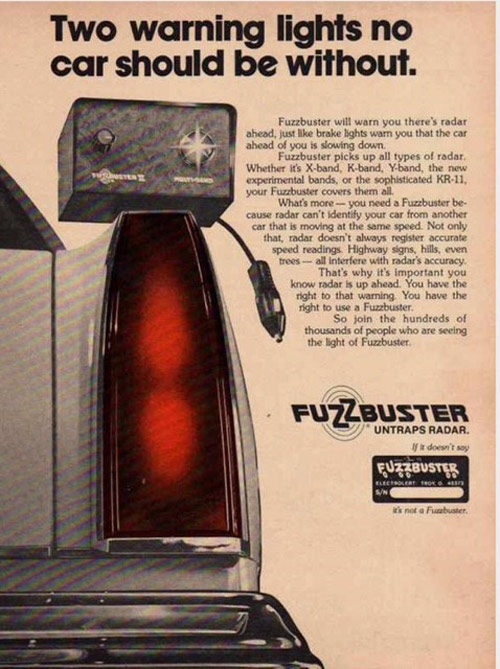

Instead of being greeted every morning with a bag of dirty letters, I now found on my desk packages addressed to “Service Editor, Penthouse:” bottles of booze, walkie talkies, cameras and lenses, turntables and speakers and pre-amps, and yes, a Fuzzbuster radar detector, which I turned over to Jim Goode so he could speed his pups out to Shelter Island in his Lincoln Continental without being pulled over by the man. For the new service editor of the best-selling men’s magazine in the world, every day was Christmas.

Besides all the free stuff and never having to pay for a meal I could now parcel out gold-bricking service articles to my writer friends, which meant I could take them out to one lunch to give them the assignment (five minutes spent listing the companies the ad staff was pitching or pacifying, an hour and fifty-five minutes getting drunk), another follow-up lunch to go over edits (what the ad department wanted changed, then getting drunk), and cut them a nice check.

My old pal Michael VerMeulen, now relocated to New York, on his way to London and an early death, became the Penthouse liquor writer and the main beneficiary of my splurgey expense account lunches.

One day VerMeulen dropped by to pick up his money for nothing. I fetched his check and was walking him out of the office when we passed another Penthouse editor. VerMeulen’s head swiveled 180 degrees and he smashed into a wall.

“Who was that?” he gasped.

That was Zelda Fleming, our femme fatale and least-likely Penthouse editor even among our staff of misfit toys. Zelda came from a patrician New England family, had attended Miss Porter’s School for Girls, and dressed in the upper-crusty style Ralph Lauren stole.

Zelda’s purview was the Penthouse Profile. Playboy had their famous Interview; because Penthouse had to be almost but not quite like Playboy, instead of Q&As we published celebrity profiles, which ranged from Marty Feldman to L. Ron Hubbard to the Ayatollah Khomeini to Robert Redford, whomever a writer could lasso into the magazine.

She was rail-thin, with big eyes and a doll face and an uncanny effect on guys: they wanted to protect Zelda from all the other rapacious men while ravishing her themselves. The only man I knew who was immune to her charms was my own boyfriend, Michael, who said to me those words every woman longs to hear: “She’s too skinny.”

Zelda merely had to waft by for VerMeulen to be smitten.

“I know someone who knows Bob Fosse. He’d make a great Penthouse profile,” pitched VerMeulen, straining his neck for another glimpse of the Lorelei who had captured his heart.

I had my doubts whether the Penthouse reader would be interested in a Broadway choreographer, no matter how famous or heterosexual, but ignored all my misgivings and wrangled a meeting for VerMeulen with Zelda.

Even though Zelda turned down his profile idea, VerMeulen came back to my little editorial pit with gaga hearts throbbing in his eyes. “I’m leaving my wife. I’m in love with Zelda,” he announced, as seriously as if he were discussing his next meal.

I marched VerMeulen over to the closest bar, P.J. Clarke’s, bought him a large drink, and gave him an earful of the Legends of Zelda, apocryphal gossip that we swapped gleefully about the Penthouse office. It was like a risqué game of Telephone; by the time a salacious Zelda story came back to me, the details were even more outlandish.

Among Zelda’s alleged suitors were:

- A Mafia capo, who enjoyed hanging her by the wrists and stubbing cigarettes out on her body.

- A European diplomat who bought her a wardrobe of handmade Belgian shoes and got his kicks by removing one pair of thousand dollar flats from her long, narrow feet and lovingly replacing it with another.

- My personal favorite, a television executive, the famed producer of 1960s game shows featuring celebrity panels. According to legend, in order to talk to his beloved the TV executive insisted on dragging his wife’s Pekinese out for an unwanted walk every evening at nine so he could duck into a street corner phone booth until one steamy conversation with Zelda proved to be too much for his dicky heart.

None of this dowsed VerMeulen’s ardor; from then on I never allowed him back in the office, always claiming that I had already popped his check in the mail.

When pressed for the facts, Zelda always laughed off every racy rumor; I was tempted to push up the sleeve of her cashmere twin set and check for cigarette burns. She wasn’t unaware of her power over men, but she didn’t consciously turn it off and on; it was magic, a gift from her own good fairy.

I was gleefully tearing open a day’s offerings to the service editor — an underwater camera! A bottle of Bacardi rum! An electric wok from some PR company who was not doing its research! — when Zelda’s tiny head popped over the side of my slanted cubicle. I hoped Zelda wouldn’t lean on the partition as her ninety-five pounds was enough to topple it.

“Hi Gay. Are you busy?”

I had unwrapped all my goodies. “Ah, no, what’s going on?”

Zelda glanced behind her and then scooted in to stand by my desk; I couldn’t offer her a seat as there was barely room for my own chair amid my towers of consumer loot.

“I have a huge favor to ask you. You know I share an office with Annie.”

That would be Annie O’Hare, the associate editor and the other fake Penthouse Pet besides me on the Watkins Glen junket of disaster.

“Could you switch offices with me?” if by office Zelda meant the two flimsy fabric-covered boards precariously perched around my desk.

“I can’t take her anymore. Her papers are all over the whole office, she never throws anything away or even files it. She is on the phone from the minute she comes in. I have to hear every detail of the bars and parties she was at the night before seven times a day! When she’s not on the phone she’s complaining and when she’s not complaining she’s smoking. Actually she smokes and complains at the same time.”

If I had been a man, Zelda would have had me at “Could you?” But I was suspicious. Zelda had an office — with a door! — and her desk faced a window, a window with an uninspiring view of Midtown but still a window, with daylight and weather. How horrible must Annie be if Zelda were willing to move into my doorless, windowless hovel at the back of the secretarial pool?

“Let me think about it,” I said.

I consulted with my pal, Senior Editor Peter Bloch, to see how bad the Trojan was in this gift horse. He shrugged. “I adore Annie, she’s smart and funny, but I don’t have to share an office with her. She can be…difficult.”

Difficult was okay, considering that even squirreled away in my back cubicle I was within earshot of Annie’s daily tirades, screeds that reverberated around the office, curse words echoing through the hallways. I could put up with difficult.

And I was still the newbie, grateful that Penthouse had rescued my fired ass and bestowed on me the best job ever. I would have taken my chances with Squeaky Fromme as an officemate to stay in the good graces of the other editors.

Under cover of darkness (5:05 pm when everyone else was already at the bar), Zelda and I switched offices.

At ten the next morning I was hunched over page proofs, my back to the door of my new office, when I felt a displacement of air and caught a whiff of menthol cigarette smoke. I swiveled, unable to hide my guilty expression as I realized Zelda or I should have said something to Annie; I couldn’t have been a pleasant surprise.

“Hi Annie…Zelda asked me to switch offices…and I…she…”

Annie marched by me and added a cigarette to the twenty-three others crushed out in her ashtray.

“So…Gay…I’m such an awful person that Zelda couldn’t stand to be around me.”

“Nobody said you were awful,” I blurted out, leaving unsaid what adjectives had been used to describe Annie.

Annie rolled her eyes, lit a Newport, and grabbed her telephone. I picked up my red pen and tried to will myself invisible and/or deaf.

Reader, I married her.

Not quite. She did become my best friend.

North Country Girl: Chapter 66 — “Dear Penthouse Forum…”

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir.

I was no longer a Viva editor, but being fired for cursing out my boss taught me to keep my mouth shut in the face of stupidity, a skill which kept me employed for forty years.

I was now the editorial assistant at Penthouse magazine, foisted on their staff by my old boss Kathy Keeton.

My new boss was Jim Goode, the executive editor, a scraggly 6’3” man with a bloodhound face who wore the same uniform of Levi’s, faded chambray shirt, and work boots every day, as if it were painted on him. Jim bore an unsettling resemblance to Lurch, the Addams Family butler, and laughed about as much, which was a good thing, as his gravely guffaw was blood-chilling, like the clanking of rusty chains.

My first task at Penthouse was to introduce Jim Goode to his newest, and probably unwanted, staff member.

I poked my head into his office. “Mr. Goode?” He looked up from the papers on his desk, fixing me with a blood-shot, Medusa glare.

“What do you want?” rumbled forth like an early warning vibration from a thundercloud.

I sidled into his office, hugging the wall. “I’m Gay Haubner, ah, I was the assistant editor at Viva, and ah, Kathy Keeton thought I might fit in better at Penthouse.”

Jim did not think this worthy of a reply but kept staring at me.

I was pretty sure any talent I had at being charming would fall on stony ground but I had to try; I knew Jim had been fired at least once from both Penthouse and Playboy, so I was hoping for a sympathetic ear.

“Ah, Mr. Goode…”

“Jim.” I took this as permission to approach.

“Ah, I heard you met Marilyn Monroe?” I thought this was an excellent conversation starter. As a reporter, Jim had covered the set of The Misfits for Life magazine, and I had been a fan of Marilyn since I was ten, when I saw Gentlemen Prefer Blondes on Saturday Night at the Movies.

“She was pasty and white, like a loaf of bread dough. If you took her arm,” here Jim grasped my wrist with his huge paw, “there would be deep indentations in her skin that lasted for days.” He released me with a shake. “Get out of here, Haubner.”

From that day forth, Jim never called me by my first name. “HAAAUUUBBNEER” he would boom out, summoning me from my lean-to in the back of the secretarial pool.

No one had clued me into what my responsibilities at Penthouse would be, but I quickly found out that the most important part of my job was taking Jim Goode to lunch, a chore I shared with the rest of the editorial staff.

Cruising on Penthouse’s oceans of cash, all the editors, even the lowly, just-hired editorial assistant, enjoyed a generous expense account. Jim was not about to use his own expense account on anything so unnecessary as a meal (he ate almost nothing, getting through the day on three lunchtime vodka martinis).

He had other things to pay for: his pampered mutts, his almost as cosseted dancer boyfriend, Kevin (who looked like a Ganymede come to life from a Renaissance painting), and French advertising posters from the early 1900s. Jim owned so many of these framed posters that there was no room to hang another in his Greenwich Village townhouse. They rested in stacks against the wall, the target of the occasional raised leg of an underwalked dog.

I’m not sure Jim Goode and I became friends. I can’t even say that he had friends. We did spend a lot of time together, at midtown restaurants, in the office, and at his place. I amused him, like a misplaced Pomeranian he picked up at the Bide-a-Wee animal shelter.

By the end of my first week at Penthouse I had taken Jim out to lunch once for crepes and martinis at The Magic Pan and twice at Mary’s, a bare-bones, fluorescent-lit joint that served unseasoned food and oversized, very strong drinks, and I still had no idea of what my editorial duties would be. I was tottering back from one of these lunches when I was stopped in the hall by a handsome young man who stuck out his hand.

“Hi, I’m Robert Hofler. You’re the new editorial assistant, right? Come into my office.”

Robert placed on his desk a bulging manila envelope and that month’s issue of Penthouse, open to the letters to the editor.

Robert Hofler beamed as if he were about to give me a Major Award. “You’re going to be taking over the Penthouse letters!”

Robert had thoughtfully selected and marked up the next issue’s letters; using the tip of his thumb and index finger, and trying not to make a face, he fastidiously pulled out a few letters from the envelope to show me what to do. After that, I was on my own.

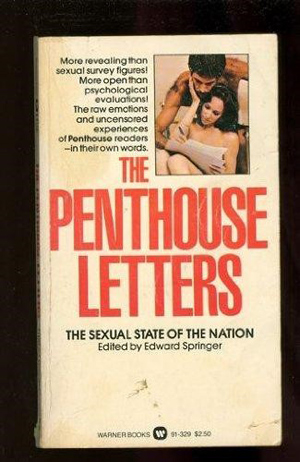

Penthouse Letters was the editorial staff’s least favorite section and (according to market research, which was squashed as did nothing to help ad sales) the most favorite of the Penthouse readers (that they actually read, as opposed to just gaping at photos of nude women). Bob Guccione, with his love of all things pseudo-Roman, titled the readers’ letters “Penthouse Forum.”

In a normal magazine, letters to the editor express the writers’ agreement or disagreement on articles in previous issues. In men’s magazines, they also include comments on the hotness of Playmates or Pets or Vixens or what have you. At some point in Penthouse history, readers began sending in letters hot-dogging their wild sexual experiences, always starting with “I know you won’t believe this but it’s true.” An extremely profitable spin-off, the Reader’s Digest-size Penthouse Forum was nothing more than letters too filthy to run in the magazine, accompanied by cheaply reproduced black and white photos of past Pets who had signed away all their rights in perpetuity.

Editing the letters section was the scut work of Penthouse, a task that had plagued almost every editor (even the gay ones, who must have looked on these letters as missives from Mars), and which was dumped as rapidly as possible on someone else. Low woman on the editorial totem pole, that was now me.

Every day, a Santa-sized bag was dragged through the secretarial pool and dumped on my desk. I was supposed to read through all the letters, looking for those gems that would titillate readers, which I typed up, correcting grammar and spelling, and embellished if the letter wasn’t detailed enough. I soon learned to recognize and dispose of letters that came in envelopes with odd red stamps. These were from prison inmates; their sexual adventures, real or made up, too often came to violent ends. After opening one letter and having what appeared to be pubic hair drift onto my desk and lap, I started squeezing each envelope before I opened it; if it felt like it contained anything besides paper, it went right in the garbage.

I can’t imagine who found this amateur pornography arousing. Letter after letter, usually scribbled in pencil on stained paper torn out of a loose leaf notebook, lovingly described encounters with randy next-door neighbors, lonely widows, incestuous sisters and aunts, vacuum cleaners and fish tanks; of adventures that occurred outdoors, in stuck elevators, bus station bathrooms, and office supply closets.

After a few months, I started casting about for anyone else I could dump this nasty hot potato of an assignment on. Each day’s mail delivery left me feeling queasy. I developed an obsessive-compulsive disorder, scrubbing my hands a dozen times a day and taking a half hour steaming hot shower as soon as I got home. I turned my back and scooted away from my boyfriend Michael in bed, claiming I was too tired or in the middle of a fascinating book. Penthouse Letters was killing my sex drive.

I could not find anyone to take this discouraging smut off my hands. I approached my first friend at Penthouse, Kathy Lowry, the on-staff writer for girl copy, responsible for transforming big-breasted, small town girls into exotic women of the world. (She was especially good at names: ho-hum Dottie Meyers became the exotic Dominque Mauré.) Kathy and I had become pals when she was suffering from writer’s block, brought on by the daily tumult of her love life.

“I’ll do it, I’ll write the copy for ‘It Takes Two to Tango,’” I volunteered, relieving her from the task of coming up with a backstory to explained why two dark haired beauties had decided to shed their flamenco dresses to engage in the forbidden dance.

Now when I asked her to return the favor, she said “Uh-uh.” Kathy turned me down with a “You can’t fool me” look. “I did those letters for a while. I have enough problems with Larry as it is.”

Kathy was a blonde Texan, lanky and wide-eyed with a slow drawl that disguised how whip smart she really was, and Larry was Larry L. King, a writer who was raking it in from his Tony-nominated musical “Best Little Whorehouse in Texas.” Larry had a reserved seat every night at Joe Allen’s while Kathy was churning out the deep thoughts of a Penthouse Pet who had one hand between her legs and the other clenching a fake pearl necklace. Kathy was convinced that Larry’s meteoric New York success meant that she would lose him. My work days began in Kathy’s tiny windowless office, listening to her whoop over what she and Larry had done the night before, or if she had spent the evening alone waiting for the phone to ring, tending to her crying jags, patting her on the back and handing her Kleenex. (After “Whorehouse” closed, a stinker of a sequel, “The Second Best Little Whorehouse in Texas” ran for all of a week. Kathy dragged me to opening night, where I sat goggled-eyed and opened-mouth with the rest of the non-paying audience, gobsmacked that such a piece of shit could actually be staged on Broadway.)

I tried to return Forum to Robert Hofler, who laughed at my presumption. “Are you kidding? I’m not taking Letters back. I’m already stuck with Xaviera; she refuses to work with anyone but me.” Robert was officially the entertainment editor; I guess entertainment encompassed the dubious sex advice doled out by Xaviera Hollander in her Ask the Happy Hooker column.

I went crying into the office of my second friend at Penthouse, Senior Editor Peter Bloch. Peter usually welcomed any interruption from his job, which was to maintain a delicate balance between Jim Goode’s insanity and Bob Guccione’s insanity. Jim was rabidly anti-government, which, considering he owed thousands of dollars to the IRS, was not surprising. Convinced that the CIA had a file on him, Jim ordered Peter to find investigative reporters who would uncover their dastardly deeds and secrets; many of these writers did ground-breaking work that was almost always ignored by the media establishment and probably by the average Penthouse reader as well.

Guccione wanted Peter to find reputable science writers who could blow the lid off the medical establishment’s suppression of dubious cures for cancer. (Guccione succumbed to cancer of the tongue a few years after Kathy Keeton died of breast cancer.)

The Jim Goode/Bob Guccione Venn diagram met with their shared obsession with the mysterious Trilateral Commission; in their eyes, these shadow men were the modern day Illuminati, bent on world domination, as evil as any comic book cabal. I think Penthouse did a twenty-part series on them.

“I can’t edit the letters anymore, Peter,” I wailed. “I’ll end up with no boyfriend and no skin on the palms of my hands.”

Peter rescued me. “We’ll give the letters to my secretary,” a woman who was gasping for her own promotion to editorial assistant.

This was great news but left open the question of what my job would be, outside of picking up Jim Goode’s three-martini lunches. I regarded these lunches as on-the-job editorial training, prepping me for whatever my real job at Penthouse would be. Jim spent lunch lecturing me on the evils of Guccione, Hefner, and the entire Penthouse advertising staff, and almost convinced me that if it were left up to him, Penthouse would have the editorial integrity of The New Republic.

These two-hour, well-lubricated lunches also taught me to do all my work in the morning. Between nine and one I was a beaver of an editor: if Frank Gilbreth had stood over me with a stopwatch, he would have been floored by my efficiency.