America Goes Dance Crazy!

Going by the numbers, America is gaga about ballroom dancing. The nonprofit USA Dance, Inc., reports a 35 percent spike in the number of people taking lessons and attending ballroom events over the past 10 years. People of all ages are trying it out. Teens like the pace—the faster the better—and older folks point to research that shows dancing keeps the body agile and reduces chances of dementia.

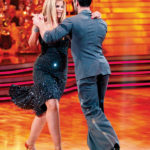

Dancing is also just plain fun. “It’s the most joyful way for me to get my exercise, get my heart rate up, and get the endorphins I crave,” says actress Jennifer Grey, who has done as much for dancing as it has done for her. As costar of the 1987 hit film Dirty Dancing, she motivated millions to head for the ballroom. Last year she had a similar impact when she earned top honors on ABC’s Dancing with the Stars (DWTS) and proved, at age 50, that it’s never too late to strap on 4-inch heels and out-perform competitors 20 years her junior.

“Dancing takes me out of my busy monkey mind and dumps me in a physical space where I can be free from thinking,” says the actress. “It’s the best way for me to feel connected and alive. I take one dance class every week, but it’s not enough. I want to be able to do it every day.”

Although ballroom dancing has never lacked for fans, its soaring popularity has certainly been boosted by shows like DWTS and its FOX counterpart, So You Think You Can Dance. Statistics confirm that Americans are giving ballroom dancing another whirl.

“People are definitely getting off their sofas and starting to dance again,” emphasizes Carrie Ann Inaba, one of DWTS’s three professional judges. “During our first season on television people would come up to me on the street and say, ‘I watch the show every week.’ By the time the second season rolled around they were saying, ‘I’m talking my husband into getting into a dance class.’ Now they’re telling me, ‘We’re taking lessons and having a ball!’”

The least likely folks are taking up dance these days. Donna Thomas, 65, was raised in a conservative church and graduated from a college that frowned on anything that resembled what it categorized as “rhythmic activity.” Yet two years after becoming a widow, Donna summoned her courage, walked into a studio near her Springboro, Ohio, home, and announced, “I want to dance.”

It changed her life. “I needed to be with people,” she recalls. “I figured I had a choice: either withdraw and stay in my shell or step out and try something new.” The “something new” included mastering the waltz, samba, cha-cha-cha, and jive. Her timing—on the dance floor and off—was perfect. At home, she was learning to operate solo and make all the decisions that she and her husband used to make jointly. In the studio, she felt the pressure ease and the responsibility shift as she became part of a team again. “I didn’t have to be in charge,” she says. “All I had to do was follow my partner’s cues and react to the music. That lifted my spirits.”

People are also dancing in the least likely places. One of the most colorful offshoots of the trend is the “flash mob,” best described as a spontaneous outbreak of dancing in very public settings such as shopping malls, school cafeterias, hotel lobbies, food courts, and train stations.

Participants, alerted to a planned flash mob through social media, congregate and wait for their cue. “People are just milling around when all of a sudden one or two start dancing,” explains Angela Prince, a spokesperson for USA Dance. Others join in and before long—in a flash, you might say—everyone’s toes are tapping, hips are swiveling, and bodies are gyrating. It’s as if one were in the center of a Broadway musical. “I remember being on a Caribbean cruise when a couple of passengers started a flash mob while we were eating dinner,” recalls Prince. “Everyone, including waiters and crew, caught the spirit and formed a conga line of about 300 people that snaked its way around the entire dining room.”

Although Prince agrees that shows such as DWTS have encouraged the ballroom craze, she credits other factors as well. “Dancing seems to experience a bump in popularity after events that change our lives,” she says, using the years following World War I and II, Vietnam, and 9/11 as examples. “Music is great therapy, and dancing gives people the opportunity to come together.”

Technology also may have a hand in the revival. Mary Murphy, a studio owner and frequent choreographer and judge on So You Think You Can Dance, says dancing provides a degree of human contact that is sorely missing since people have come to rely on the Internet as their primary mode of interaction. She works with elementary and middle school students to introduce them to what she calls the language of dance. “Some of the kids come kicking and screaming into the classes, but teachers tell me that they see positive changes within a few weeks.”

The idea of a young couple joining hands as the boy guides his partner and the girl follows his lead, is certainly part of the appeal. Dancing allows young people to communicate without the pressure of finding the right words. “Kids who have behavior problems naturally calm down and find new ways to express themselves,” says Murphy.

When it comes to the therapeutic benefits of dancing, Murphy can speak from first-hand experience. She underwent treatment for thyroid cancer a year ago and faced the possibility of losing her ability to talk. Today she is cancer-free and as exuberant as ever. She used dancing to help prepare for surgery, and she integrated it into her recuperation regimen. “Getting that diagnosis and hearing the word cancer was the one time in my life I just wanted to shut down and have a major pity party, which I did for a couple of days,” she admits. “Then I decided I absolutely had to keep my body moving. So I added a lot of activities to my pre-surgery program to increase my lung capacity. I did yoga, pilates, and dance exercises every day. I wanted to be in the healthiest condition possible.”

Her plan worked. She sailed through the operation and the recovery that followed. The reason? “I absolutely believe it was because of dance.”

Fans of the two hit TV dance shows can attest to similar dramatic effects that dancing has had on several of the competitors. “Kirstie Alley immediately comes to mind,” says Inaba. Dubbed “the incredible shrinking Kirstie” because of the weight she lost during Season 10 of DWTS, Alley decided to wear the same costume on the show’s finale as she wore for the initial competitive round. This proved to be a challenge for the wardrobe staff because the dress had to be downsized by 38 inches. The combination of a healthy diet and rigorous dancing had caused her to lose almost 100 pounds.

“A lot of times our self esteem is determined by the shape we’re in and how good we feel about ourselves,” says Inaba. “Dancing brings you back to a place where you feel physically confident about your body because you’re strong again. Your core muscles are working; you’re in shape; and you’re in tune with your body. I watched Kirstie rediscover her confidence last season.”

Dancing also can replenish a zest for life. Donna Thomas, the conservative-turned-dance-enthusiast, certainly discovered this when she was still newly widowed and stepped out of her comfort zone to sign up for ballroom lessons back in Ohio. Over a period of time, she became so engaged in dancing that she was a regular at Friday night dance parties, and her skill level rose to the point where her instructors encouraged her to enter competitions. Although she no longer competes, she still has the sassy black dress and high heels that she wore when performing, and somewhere there’s a scrapbook of photos, certificates, and ribbons. Her favorite memory, though, doesn’t involve winning prizes or gaining recognition. It’s more personal. “I remember the night I invited my kids to attend a dance with me,” she recalls, with a laugh. “You should have seen their faces! They were just so surprised at how good I was!”

Secretariat Speaks: “A Century of Derbies”

Being the true thoughts and reflections of Secretariat himself, as ably noted and transcribed by our best horse intereviewer, Starkey Flythe, Esquire.

Originally published in 1974.

The first week in May. The jockey’s silks are as bright as a bridegroom’s cravat. We are rubbed to the patina of antique Georgian furniture. Thirteen of us. There is the soft smell of leather and light tweed, earth that a hundred years of horses have kicked up and a hundred years of juleps in silver stirrup cups have wet down. And rising, ever so faintly, above the crowd, over the salt tears that edge out of eyes when “My Old Kentucky Home” blares, a whiff of roses. (I just gave you that hit of purple prose to dissociate myself from those other talking equi and muli, Mr. Ed and Francis.)

Anybody can run in it. At least if they’re registered by the Jockey Club. And there’s a story about a horse from out West who was asked not to, but whose owner insisted, until the nag was entered only to refuse to go into the starting gate, but once in with the help of all the King’s men, refused to go out, and finally out with the same aid, ran backwards. But “anybody” rarely wins it. Of the ninety-nine starts, forty-three post-time favorites have won.

IT is the ninth race in a day of ten. Post time is 5:30. And for the moment, Churchill Downs is the center of the universe. For racing? No, not just for racing. For radiance. The horse that wins will wear, not just as long as his head is above the turf — but forever—a crown of glory. A brass name plate on his turn-out bridle. A plaque on his stall door. He will become a living moment in the big and noble hearts of Thoroughbreds. He will never be referred to again as a stakes horse, normally a compliment opposed to being called a “plater”— one who competes for trophies. He—or in one case, she—will always be a Derby winner.

The money is $125,000 to which are added nomination fees, entry fees ($2,500) and starting fees ($1,500). The mutuel pool my year was $3,284,962. The total bet, over $6 million (a record). The value to the winner, $155,050. Which isn’t bad for 1:59.4. Which was a record for the track. Which, noted the Daily Racing Form, was fast. But nothing compared to me. I ran faster the last quarter than the first. Went by the stands last first. And first last. Which is when it counts.

Elation. True elation. It is a rare experience. Mares have said when they’ve dropped a foal and seen it, wet from birth, struggling to its feet awkward as a chapped-lip whistle—and seen that its points were those of a champion—straight and flawless legs, trim and tight knees and ankles, and that the colt would race and someday people would know his name—then they have experienced elation.

Elation came to me-more I think at the Derby than at any other race. I didn’t mean to be a ham, though Mrs. Tweedy says I am—”He pricks up his ears and gazes off nobly into the distance when he hears cameras clicking”—what do they expect of you when they take a million pictures of you?— one photographer even has a recording of mares in heat he plays to get our attention—but the grandstands seemed the place to lead. Ron Turcotte was no more than a fly or a gnat on my back when he struck me with his whip leaving the far turn. Then he switched it to his left hand. Flashed it. It seemed my lungs swelled, like water wings, lifting me into the ether—I never touched the ground again —the rest of the world seemed to have wound down to a snail race. I could hear the rows of men, see their arms high, know that it was me they were calling—almost to come back—but I had gone beyond them and could never go back. My heart was a boiler of blood. It seemed to me it might explode, but I could not stop. Then something outside of me took over and I was not merely me anymore. I was Pegasus, flat and lean, hurled against the sky. There was no resistance. The elements lay docile at my feet. Until I had passed; then they shoved me. A pair of wings crossed the finish line. I was already in the winner’s circle and Mrs. Tweedy was leading me out to the roses.

I could remember Sham, the horse I competed with who beat me in the Wood Memorial, and who came in second at the Derby, his mouth the color of roses too. Only it was blood. When we were being loaded into the starting gate. Twice a Prince—he ran next to last—perhaps he knew he was going to—refused to enter his stall. He reared up and threw his jockey. Shoes clanged against the metal of the stall divider. Sham’s head hit the gate, drawing blood, nearly knocking out his front teeth. Ron, smart as the horsefly he is, hadn’t loaded me in yet and turned me away from the clatter. Somebody got Twice a Prince out of the gate and soothed him. They got his jockey back up and all of us were in our stalls and off.

My hood is checkered—the colors of home—The Meadow-blue, white—it is like the flags at a Grand Prix-and on the backstretch I could see the blood flying from Sham’s mouth and right up to the wire I knew he was there, running fine, fast, rising over the pain and fear he felt. It would have been his race—any year but this one. Two who in any company would shine were this year against each other. Still, I could never have known myself against any but the best. Sham is the best. Races are never between the quick and the dead. They are between the quick and the quick.

There’s another horse I have to name, too. My stable mate, Riva Ridge. Riva is a dark bay—almost mahogany with sable legs and mane, a shortness of grace and going; he now stands at stud across the lane, a paddock away from me, at Claiborne Farm. I see him, silhouetted, motion even standing still, and there has been, at times, envy between us. When he won the Derby—the ninety-eighth running—he was the center of attraction. When I came along, there was trouble. People used to come see me in my stall, passing Riva Ridge. And he knew it and would turn his backside right up to the stall door, letting them have a taste of their own fickleness.

Riva was the horse that first brought glory to The Meadow and made us all celebrities. And when Christopher Chenery, who founded The Meadow and gave us all our chance and had always wanted to have a Derby winner, was so ill and down in bed, Riva won and we don’t know, but we think Mr. Chenery understood, sick as he was, that he had a winner, and he went out happy.

Photo by Tony Leonard.

Sometimes I think about the hardships of racing. About the cold morning workouts. About the other horses, the sting of the earth as it flies up and hits your belly, the closeness of the other horses, their fear and your fear, the tricks unscrupulous jockeys sometimes play on you, the animosity among trainers in the barns and stables at racetracks, the way we know we are going to be run (instead of the usual four quarts of oats for lunch, there’s half a quart, and the hay outside the stall is taken away), the way they—grooms, trainers, hands—try to make you relax, and how it never quite works. When they are nervous, you are nervous. “Horses ain’t like humans,” my friend and groom of last year, Eddie Sweat, said. (And we can thank the great Four- Legged One above for that.) Eddie says, “They have a mind of their own and you never can tell what they’re going to do. You think you have them settled down, but something happens, and it might bother them.”

Well, we’re hyperopic (farsighted). And we can’t see things close up unless our noses are practically touching them. Nor can we see directly in front of us, but to either side, behind, and to some extent above and below.

Stick your finger out in front of you. Now blink your left eye. Then your right. Fast. The finger seems to jump. Your eyes are an inch apart. Ours are six. Think how inanimate objects spring out at us. Then think that our ancestors knew running away was their only defense. Far-sightedness shows us the enemy at a distance. Farsightedness creates time for head starts.

So against this heritage—not to mention the Arabians bred with English mares 200 years ago— the registered Thoroughbreds in America are descended from three sires: the Byerly Turk, the Godolphin Barb and the Darley Arabian—we are expected to perform in a world where people are our only friends, where stall walls are too high to enable us to get aquanted with any horses. Throughbred is a distinct breed of horse, just like Morgan, Hambletonian, Percheron or Hackney. We have a dished or straight profile, a long, slender neck, sloping shoulders, fairly short back. The width of brisket—the space between our forelegs—is large, making room for the great heart of a Thoroughbred and the powerful lungs. Our muscles are flat and stringy, mane and tail thin and fine, veins violin strings, skin so thin we suffer terribly from flies and hot weather. We are high-spirited, but rarely mean or stubborn; ruined by rough treatment and easily gentled as a foal by kindness. Courage and quickness, spirit and delicacy mark us—no horse in the world can stay with us on the track; none can outjump us in the field. And we all have the same birthday, January first. At a year we are considered to be seven. At three, we are one and twenty and our lives—in some stallions’ cases—are paved with woo.

People say Ron Turcotte and I have our own style, that we break from the gate and then drop back; that’s a nice thought. The competition isn’t a bunch of drays, though, or the race an amateur version of The Iceman Cometh. They’re the fastest horses in the world and they’ve been trained all their lives for this day.

We have our own starting gate at The Meadow—and at Belmont, where I trained. So we’ll know how to break. So we won’t be afraid. Mrs. Tweedy thought of that and discussed it with Lucien Laurin, my trainer. (I love it when people discuss around us, their voices are quiet and soft—they don’t want to upset us—vexation never won a race.) Lucien said he thought it was a good idea.

I like Penny Tweedy. She said the first time she saw me, “Wow!” And it stuck. “The Wow Colt.” “The Wow Horse.” She’s sort of like me. Well bred (old Southern family-The Meadow belonged to her father’s people before the War between the States), well educated (Smith, Columbia University-business administration), she knows what she’s doing, and she does what she knows, and pretty (people cheer when they see her—and pretty is as pretty does so she got a public relations firm to handle the dishing out of me as a public figure), and, heaven forgive me, well fed.

Most stallions do fairly well on twelve quarts of oats a day. I like sixteen. And I nibble hay while the sun shines, and after it goes down, I have a special supper. A sort of mash of oats fortified with vitamins and minerals plus carrots and “sweet feed”—molasses-coated grain. Some horses won’t eat after a big race. But it just works up my appetite. I hate to use the word tub, but bucket doesn’t really size it up. One of my grooms describes me as a “neat eater.” “He has a sip of water every now and then between his mash. Then he picks up any stray buds on the floor and varies everything with a few wisps of hay. But, lordy, the amount.”

Well, consider my size. Twelve hundred pounds. Supported on legs less than yours. Like a bumblebee or a C-47 (from an engineer’s point of view), I shouldn’t be able to fly. And I’m still growing. My girth is seventy-five and three-fourths inches—about an inch more than Man 0’ War (who was also called Big Red) and I have to have a custom-made girth to hold my saddle. I can cover twenty-five feet in a single stride. You can see how that would eat up the Derby track, one and a quarter miles.

Ron always says, “I like to let him find his feet. Then he gives me his speed when I chirp to him.” Sometimes, the “chirping” gets lost in the noise of the race and he calls out with the crop. I don’t like it. I never have. I remember when he first used the whip. 1972. It scared the fodder out of me. I ducked into another horse and our number was taken down for a foul. I had begun my career in racing at Aqueduct—Fourth of July—appropriate date for the “horse of the century”-when another horse bumped into me at the gate and knocked me out of my direction. “If he hadn’t been such a strong horse, he’d have gone down,” the jockey said. Still, I got myself together and finished fourth. Since that day I’ve never been out of the money. Unbeaten—a good word in most sports—never really applies in racing. Man 0’ War and Citation were beaten. I’ve been beaten. But finished first in eleven out of fourteen races. How can we, after all—mute according to our masters—say we feel bad and want to stay in the barn, that we are under the weather or the weather is under us. At the Wood Memorial at Aqueduct in April, a few days before the Derby, I came in behind Angle Light and Sham. For the drama of the Derby, I suppose, I couldn’t have done better had I tried. Many sportswriters and racing experts said I’d blown it. Of course the odds are the real sportswriters. And they remained $1.50 to $1.00. Sham’s were $2.50 to $1.00 and Angle Light’s were the same as mine. Angle Light finished tenth and Sham, of course, second. So from the gate we are fighting. Even when

we drop back. Strategic withdrawal you could call it. But the more you spot the competition, the farther you’ve got to go to catch up. Then you have to pass. And keep up. They said at the Derby when we swung around the outside, passing horses until only Sham was in front, we could never keep up such a rally to the finish. Just before the midstretch, I caught him—perhaps it was the sting of the whip I feel I’d have got him anyway—and beat him by two and one-half lengths for the fastest Derby ever.

I often think green and while are the colors of the South. They know how to hang deep green blinds on spanking white walls, or how to plant a magnolia against a snowy column. That’s the look I get saddling up in the paddock. Thousands of tulips blooming just for us. The whole Derby is like a flying flag. Patriotic, colorful, wild in the bluegrass breeze.

The moment the jockeys touch our backs—one of my friends said they look like squabs turned up in a Christmas pie with their little rumps—we start for the track where the outrider in a red jacket, usually on an Appaloosa, meets us and leads us out for the post parade and the warm-up. Like athletes—why say “like” athletes, we are athletes—we have to warm up our muscles.

I love the far side of the track—it seems almost a far country. Even on Derby day when the inside of the track is filled with bodies—mostly young people with their shirts off for the warm May sun so that the track seems to be some giant public pool—quite a different sight from the boxes on the other side which cost $1,600 for the day—the noises hang in the air, a distant fantasy, a conglomeration of the great ocean liner Churchill Downs seems to be, its restaurants, its bars, its vast halls and betting windows, its milling throngs, closed circuit television, its wild people who never go outside to watch the races but sit, eternally glued to their racing forms—it would seem they would bet on themselves before they trusted in us to bring in their fortunes—all that seems a million miles away. On this side is still the barn. (Churchill Downs has 1,200 stalls, 50 barns.) And the warmth of the fresh hay, the cool spring water they give us, mingle with the memory of the nice snooze I had before I came here. (Ninety minutes I lay down for. Most horses are so nervous they paw through the floor.)

The outriders are urging their horses on, eyes—theirs, not ours; ours are fixed on the distance of around and back again—study jocks and mounts, looking, hoping for weaknesses, faults to be taken advantage of. The condition of the track, “That loam you have at Churchill Downs sticks to your face like cement when it flies up,” says one trainer: The brass of the post horn—a recording even on Derby day—becomes, with the shouts and urgings a welter in our ears; the gate breaks and the last of life for which the first was made begins. Three camera towers grab us from three different angles, freezing us in our rage for honor. Motion picture film flies over the wire to a hot developing room; is sent back to the stewards for viewing any infractions: horses bumping, crossing over, impeding the progress of another horse. None. A clean race.

There’s a party in the Director’s Room after the race. Champagne and very select company. Seventy-five invited guests. I heard Bob Gorham, one of the officers of the track, bemoaning having to turn down some senator. I’ve heard them talk about that room, prints of Epsom, our Derby, now a print of me with Ron and Lucien, the six tufted black-leather chairs, scrolled, Victorian, deep, downy. The quiet butlers who fill your drinks before they’re empty. Of course, we have our own party. But we still had the Preakness and the Belmont to go.

Now above the roses, I wear the Triple Crown, the first winner of it in twenty-five years. Perhaps the Belmont and the Preakness were more spectacular runs for me—thirty-one lengths beats the dead heat syndrome—but nothing ever seemed to capture the stopped-heart thrill of racing like the Derby. And even more than my being the Triple Crown winner, people—especially those who come to see me in Kentucky where the land rolls gently, almost sensually—those people always say, “Turkey dinner, Derby winner.” And thank heaven I’m protected. Fans would grab for souvenirs like I was a rock star. And, after all, I only have one suit.

Sometimes, I think of racing days as I watch the mares and colts frolicking across the meadows at Claiborne, the beautiful Hancock farm near Lexington, Kentucky, and the swans stretch their lovely necks on the meandering stream across the road from the white-columned house where the Hancocks have lived for so many years, and I wonder about the value placed on my blazed head. Six million dollars. Plus the money earned racing. Could anyone be worth that? And calling me ‘horse of the century.’

If another horse wins the Triple Crown next year, will he be the horse of the century? That horse won’t have the three white socks and blaze, won’t be a public relations item, won’t be the subject of postcards and tee shirts, the recipient of millions of letters, and the donor— yes—of charity on a colossal scale—no, I don’t just mean the taxes my owners have paid on my earnings. I mean the windfall to the state charities which benefit from betting. People were so thrilled, especially the two-dollar bettors, at having bet on me and at my winning, that hundreds of thousands of ticket holders did not cash in their tickets, preferring to hold them as souvenirs. “And that other horse won’t be playful as a puppy,” says a stableman at Claiborne.

“You just don’t think of a horse that strong,” says Mrs. Tweedy, “being that kind.” “Secretariat’d never be mean,” says Lawrence Robinson, my best friend at Claiborne, and the man in charge of the breeding barn.

There are other friends here too. “Snow,” a man whose face always seems to get into every picture with me. Pick up any magazine, and there’s Secretariat. And Snow. Then there’s “Buster Brown,” or some people call him “Charlie Brown,” a half cairn terrier, half mongrel, and four other halves. He slips into my paddock under the gate—”He wouldn’t dare go into any of the other stallions’ paddocks,” says Lawrence, and I have to chase the little mutt out. Then there’re the Hancock racing colors—bright orange and black—and they’re friends too. I know somehow the days of glory aren’t really over, that a new crop of colts will be bounding across the meadow next year and that they will bear my blood and the blood of my sire, the great Bold Ruler whose stall is home for me now, and all the way back to the immortal Eclipse, the immortal English sire of the eighteenth century. And I remember five hundred of the darkest, reddest roses; small, tight buds, thorns stripped, draped over my withers. And I know of the pride of the woman who makes the rose wreaths and has since the 1930’s. “Never,” she says, “has a single rose fallen off before being put on the horse.” And I think that maybe one day, one of my sons will stand there and receive that same glory. And to tell the truth, I’m a little jealous.

The Unforgettable Natalie Cole

In her book, Angel on my Shoulder, Natalie Cole tells the story of her parents’ move to a posh, all-white suburb of Los Angeles in 1947. Residents promptly informed Nat King Cole that home ownership was restricted to whites who celebrated Christmas. People of color or diverse faiths weren’t welcome because neighbors “didn’t want any undesirables moving in.” Cole nodded. “Neither do I,” he assured them, “and if I see any, I’ll be sure to let you know.

The Coles stayed put, fending off lawsuits and enduring cruel signs posted on their lawn. “My parents were very strong people,” says Natalie. “My dad wasn’t about to let anyone tell him where he could sing, where he could eat, or where he could live.”

Natalie was only 15 when her father died of lung cancer at age 45—he was a three-pack-a-day smoker—but she shares many of his traits. A gifted singer, she has 21 albums and eight Grammy awards to her credit; she’s a devoted Christian who admits that when she looks back on her life, “I see the many times I’ve been saved from bad situations.” And, like her dad, she refuses to back down, regardless of the challenge. Diagnosed with hepatitis C last year, she underwent painful treatment for the virus and emerged virus-free but with damaged kidneys. Her jam-packed performance schedule to promote her new CD was scrapped in favor of a new schedule. She is now on dialysis three days per week for three hours and 30 minutes per session. This regimen will continue until her kidneys regain their function (a long shot) or she decides to have a transplant. “I’m still thinking about that,” she admits.

Her latest album, Still Unforgettable, has done well in spite of her limited visibility. Now she is stepping up her public appearances, taking care to arrange for dialysis on the road between engagements. The Post caught up with her a few days before she departed for a major concert in Milan, Italy.

First of all, how are you feeling?

My energy is back, and my stamina is great. In many ways the chemotherapy (for hepatitis C) and dialysis (for kidney disease) have saved my life. The treatment schedule is a chore, but once you realize that dialysis is a part of your routine, you just do it. I was able to go back to work a couple of weeks ago, and although I was looking forward to it, I was a little nervous. We did two shows, back to back, with a full orchestra. It was great! The audience was really, really responsive.

The Post interviewed your dad in 1954 when he was preparing to record a children’s album with you and your sister. You were 4 years old, and he was concerned about your habit of yawning whenever you sang. Your new CD has you doing a virtual duet, Walking My Baby Back Home, with Nat King Cole. Yawning isn’t a problem, but how difficult was it to blend two voices, one of which is preserved on a recording that dates back 57 years?

My father had a very special sound, and thank God I inherited some of that. Not everybody can sing with Dad, which is why a lot of people didn’t attempt to record some of his songs until I did the Unforgettable: With Love project in 1991. I had been singing with him since I was a little girl, so I wasn’t intimidated by his voice, although his phrasing made me crazy. That’s when I realized what a great singer he was. As for the technical part, our engineer, Al Schmitt, was amazed at how well our voices blended. Al would look at the graph on the mixing board and the lights were exactly at the same level. He had never seen anything like it. I guess that’s part of my heritage, and it’s not something that I had to work at too hard. Singing with my dad is fun…a labor of love.

How did working on the new album help you emotionally deal with what was going on outside the studio—the hepatitis C diagnosis?

Music has always been a healing balm for me. It’s the one thing that really makes me very happy. I was grateful when we were working on the album that my voice wasn’t affected by my diagnosis or by my illness. The hepatitis didn’t get severe until I was finished in the studio, so I was able to work steady, work well, and keep my focus. Of course I didn’t have much of a choice since I was the producer of this project; I needed to be in charge. But for all of us in the business, music is what can get us out of any kind of funk that we’re in. It takes over, and that’s a beautiful thing.

You’ve been very candid about tracing your hepatitis C to the heroin addiction that you overcame more than 25 years ago. How have you made peace with your past?

I think it started with learning to be honest with myself. I had the privilege of spending six months in rehab, and it changed my life. One of the things that the twelve-step program teaches us is to be brutally honest. When you’ve been into drugs and you’ve almost lost your life and almost ruined other people’s lives, you have to take responsibility for it. A lot of people aren’t able to do that, especially in show business where there’s a compulsion to cover up everything and try to come off as if you are perfect. But people like you better when they find out that they can trust you. Now I can look at myself in the mirror and know that I’ve done the best that I can, and I don’t have to cover up anything. I think that’s why people respond not just to my music but to me as a person. They feel there’s something behind the song; they understand that I’m not faking anything.

How has your illness affected you aside from the predictable physical changes—the fatigue and weight loss?

I’ve become more of a day-to-day person. With a disease like this, you don’t take life for granted; your mortality becomes very much a part of who you are. I didn’t realize how close I had come to dying when I had the episode with my kidneys failing. Now I’m not in a panic to get things done. I have more clarity. My attitude has changed; I’ve got a little more patience and a lot more compassion for others. God has been really good to me. I’ve had a great life, and for the most part, I’ve been a healthy person. In two years I’ll be 60, and I look at my mom—she’s 87—and I think, “I hope I have some of her genes!”

Speaking of genes, some people say that as we get older we become more and more like our parents. Can you relate to that?

Hmmm…I think I’m a people person like my dad. He was very warm with people, and in return, people gravitated toward him. Also, my dad’s faith was important to him. His father was a Baptist minister, and his whole family was very active in the church. There was a time in my life, back when I was in my 20s, that I was on probation (for drug use). I could have gone to prison, but God looked out for me. Instead, I ended up staying with my aunt in Chicago for several months. She was such an important influence on me. Being with her put me in a spiritual environment at a very critical time in my life. Since then, even though I’ve continued to go through a lot of issues, I’ve known that God has his hand on me. There have been so many times that I’ve felt covered by God.

Last year had its highs and lows for you. As you look ahead, what is your hope for 2009?

Good health is always my first hope. After that, I would love to see our country become more spiritually minded. We need to lose our materialistic ways and reach out and help other people. As Americans, we need to see more of the world and understand how the world sees us. Sometimes we get confused. …We think we’re here to make ourselves happy, but that’s not it at all. We’re here to be of service to others, and that ends up making us happier than we could ever imagine.

What is Hepatitis C?

Deaths due to the hepatitis C virus (HCV) are likely to double or triple in the next 15 to 20 years, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The reason? Most HCV sufferers—an estimated 150 million worldwide, 4 million in the United States—aren’t aware that they have it; therefore, they don’t seek treatment until it’s too late. Here’s what doctors know about the elusive virus:

- A blood-borne disease, HCV often goes unnoticed because victims experience no symptoms for many years.

- Needle sharing among drug users is a common mode of transmission.

- Left untreated, HCV can damage the liver and is the leading cause of liver transplants.

- Successful drug therapy is available, although the FDA-approved antiviral medicine can cause side effects.