The Art of the Post: The Artist Who Loved Trains

Read all of art critic David Apatoff’s columns here.

Some artists specialize in painting landscapes. Some focus on painting portraits. Peter Helck painted trains.

Helck found as much excitement and inspiration in trains as other artists found in love stories. An article about Helck in American Artist magazine said, “he paints [railroads] with authenticity and with a dramatic power which expresses the romantic appeal these things have for him. He is passionately fond of locomotives; they are frequent subjects of his canvases.” Helck put it more bluntly: “[I’ve been] wacky over steam locomotives all my life.”

Helck was born in New York City in 1893. By the time he was 10 years old, he was spending his allowance each week on the model trains at Coney Island. His first art jobs were working for the art departments of local stores. As his reputation grew, he graduated to illustrating for magazines such as The Saturday Evening Post. Publishers spotted his special talent for painting machinery and industrial equipment, so when an assignment called for a picture of machines such as trains or old cars, Helck became the first artist they called.

At age 30, Helck moved to a large farm in Boston Corners, about 100 miles north of New York City. On his farm he had room to store his growing collection of battered old cars and tractors. When he wasn’t painting, he enjoyed working on them in his barn.

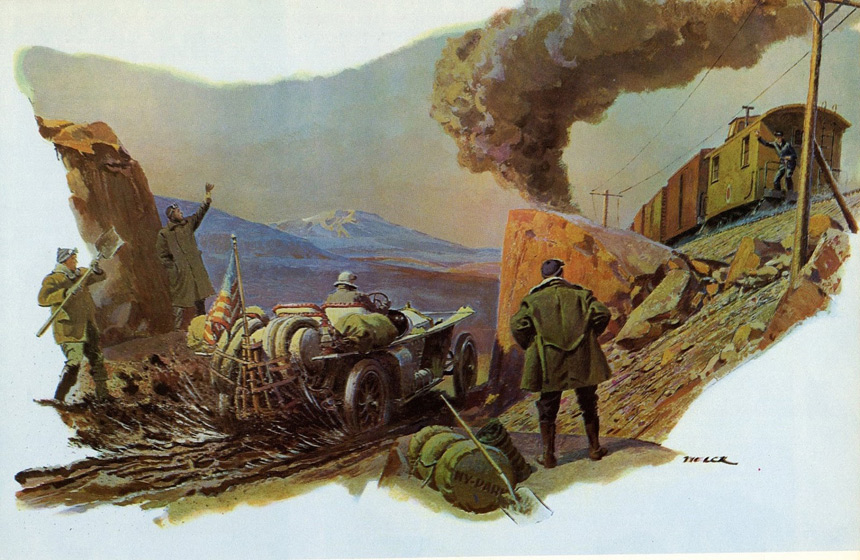

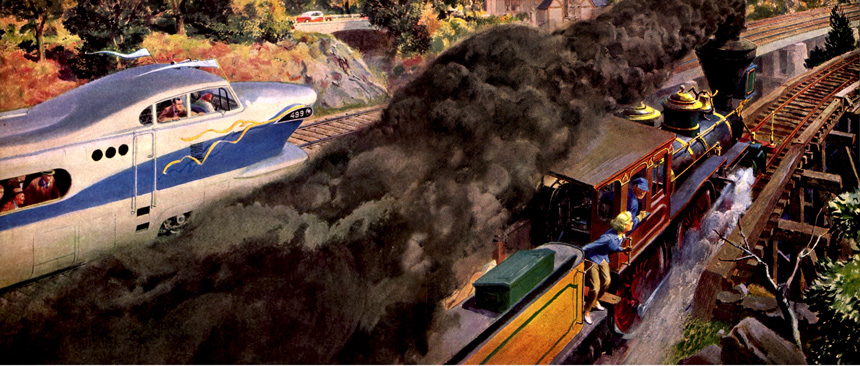

One of Helck’s favorite things about illustrating trains was that he occasionally wrangled permission to ride in the engine cab of real trains, sketching details and getting a sense for the experience. While illustrating the story “Thundering Rails” for the Post (March 27, 1948) Helck was able to ride in the engine cab of a train to Albany, New York.

He recalled breathlessly, “I got to work in an atmosphere gloriously dense with soot and smoke and generously affording the dramatic night lighting effects of which I never tire.” Of course, sometimes he forgot to ask permission. More than once he was kicked out of a train cab for trespassing.

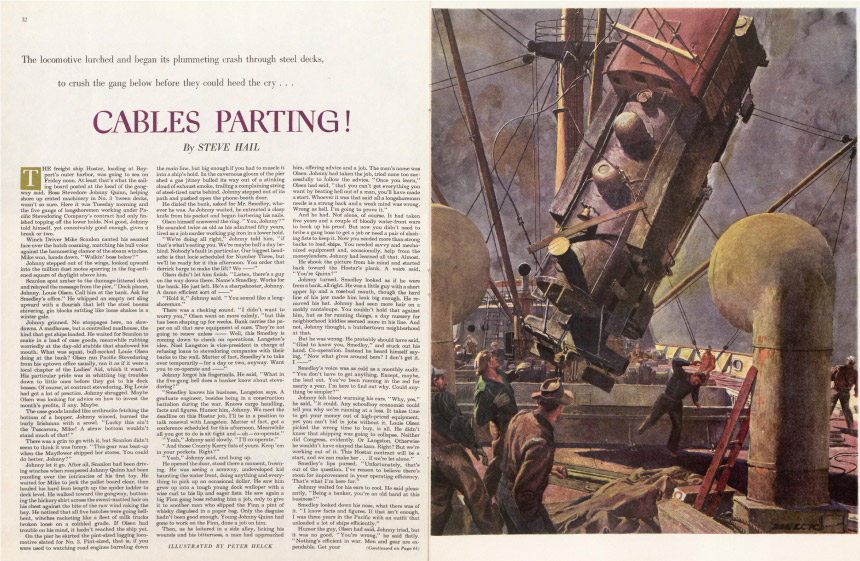

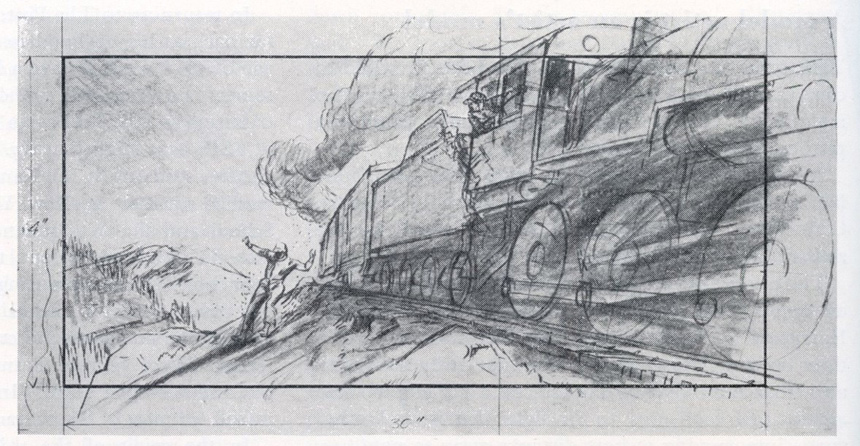

He also ran into trouble because he sometimes made the train, not the people, the star of his painting. As you can see from the following preliminary sketches for the story, “Screaming Wheels,” (The Saturday Evening Post, February 19, 1949) Helck started out by giving the starring role to the train, leaving a only a minor role for the human (who was supposed to be the center of the story).

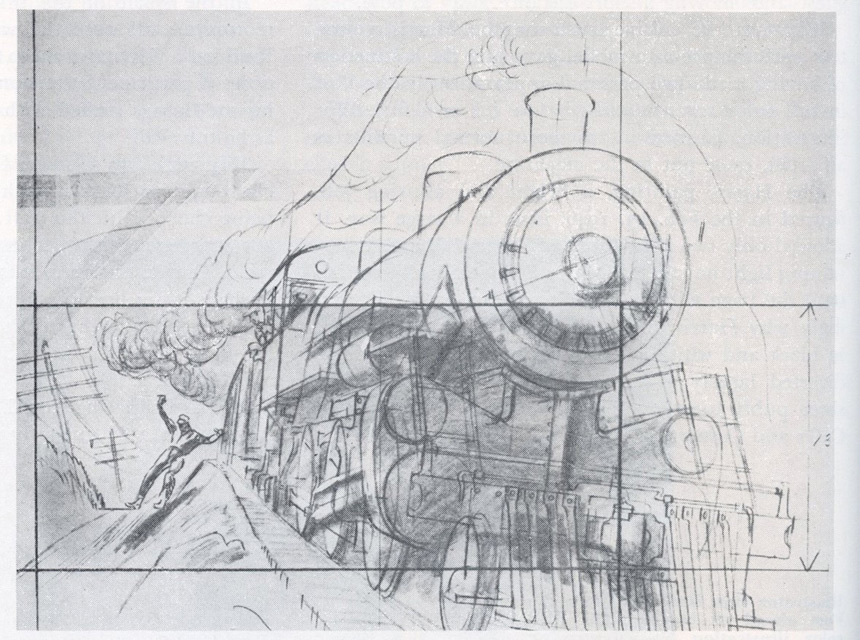

In the next drawing, Helck was nudged into increasing the importance of the man jumping off the train. Still, the train remained too prominent, so you can see how Helck cropped his beloved train to diminish its role even further.

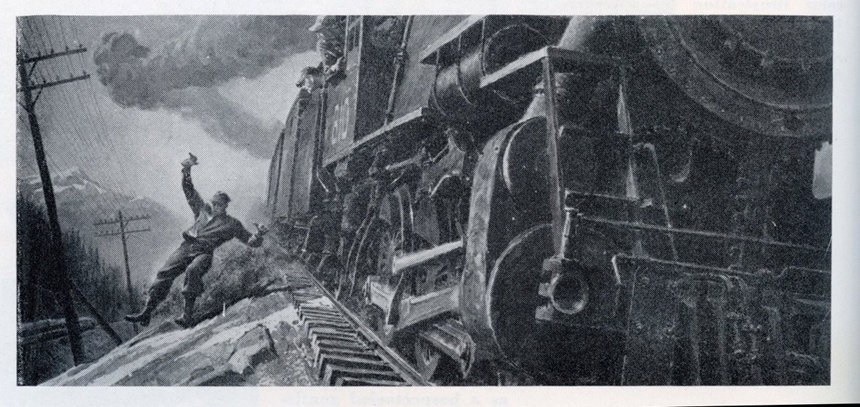

Here is the final version as it appeared in The Post, with the train veering off to the side and the man in the central role.

For another assignment, Helck painted a locomotive with smoke belching from the smokestack. When he delivered his finished painting, a junior account executive didn’t care for the dirty smoke, so he rejected the painting. He instructed Helck to take it back and paint a cleaner version minus all the smoke. However, when the art director saw the cleaner version, he was livid. He called Helck and asked him to restore the smoke, grumbling, “I was out of the office, sick, and that so-and-so went over my head. If I send it back will you put the guts in it again?”

Because Helck understood trains from top to bottom, he was even able to imagine how a falling locomotive would look. Obviously, no one could suspend a massive locomotive mid-air for Helck to paint, but he could project one in his mind. What other illustrator could pull off such a feat?

Most artistic traditions have been shaped over thousands of years. Artists in ancient Greece and Rome studied the human body and developed conventions that were passed down by artists through the ages. Renaissance painters made great strides in learning how to paint fabric and metal surfaces. Hundreds of generations have explored different approaches to painting the human face.

But trains were different. Trains were still relatively new when Helck was born, so he could not rely on generations of artistic solutions. Artists were still shaping the basic traditions for painting the speed, power, smoke, and other features of a locomotive. Helck’s love and enthusiasm for trains made him well suited for inventing and popularizing their images.

Classic Art: Sporty Race Cars

by Frank Leon Smith

Illustration by Peter Helck

Click image to enlarge.

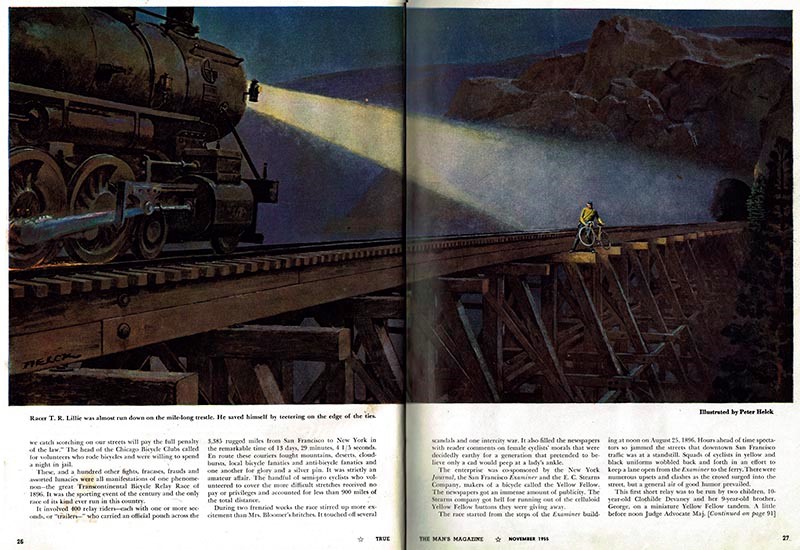

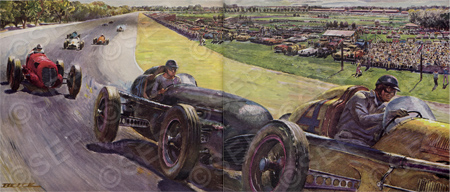

“Motors roaring around the track, skidding on the turns, battles for position, shouting crowds—could even these make the heart of the girl from Boston beat faster?” Frank Leon Smith asks in the 1946 story “Keep the Girl on the Fence.” We don’t know about the girl in the story, but it works during race season every year, in recognition of which, we bring you some midcentury illustrations of race cars.

Auto racing stories were popular in the Post in the ’40s and ’50s, and although the titles were sometimes melodramatic — “Murder Car,” “The Crowd Screamed” — a common denominator was the exciting illustrations by artist Peter Helck (1893-1988).

by William Campbell Gault

Illustration by Peter Helck

Click image to enlarge.

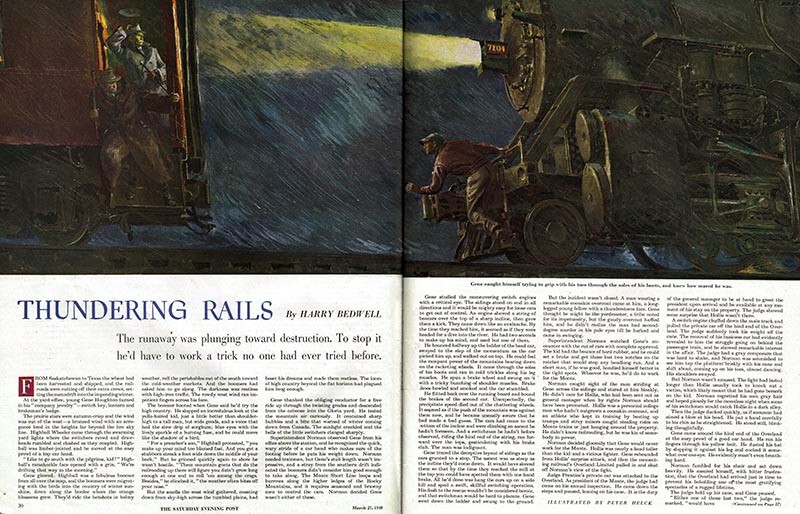

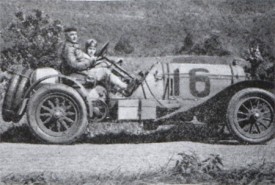

“The black job roared into second place, but its driver wasn’t trying to win. He wanted to kill the man ahead,” declares the intro to 1951’s “Murder Car” by William Campbell Gault. Although some of the fiction was overly theatrical, Helck was serious about the fast-paced scenes. He was also earnest about car racing, a passion honed as a young man when he witnessed the historic 1906 Vanderbilt Cup Race, featuring an American car built to beat the Europeans. Known as “Old 16,” the car won the Vanderbilt two years later in 1908.

from “Keeping Posted”

December 28, 1946

Click image to enlarge.

“Old 16 was built when the American automobile, then only a fast-growing youngster, first challenged the European builders,” wrote Post editors in 1946. “Motoring was just becoming something more than a fashionable—and pretty daring—sport. Two things were at stake: prestige and the booming American automobile market. Citizens of substance, if they had decided to trust their lives in one of these smelly new gas buggies, liked to buy European cars. There was a feeling that nothing built on this side of the water could equal such swank European cars.”

Helck acquired the legendary race car in the early ’40s. “Every time I take Old 16 out for a run, I recall the men who handled cars of that era—under the road and tire conditions they faced — and my admiration for their capabilities becomes a bit fanatic.”

by William Campbell Gault

Illustration by Peter Helck

Click image to enlarge.

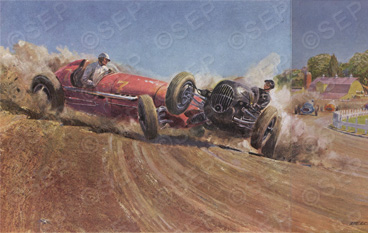

“It was the last lap of 100 miles of murder that he saw a car broadsiding in front of him,” the lead-in to this 1952 story declares, “ready to spill—and [here comes the title], ‘The Crowd Screamed.’” Melodrama aside, this is an all-but-live-action illustration.

Though Helck was best known for these fast-action scenes, he did a great deal of industrial commercial art as well. One testament to the variety of his illustrative skill is his work for Post sister publication, Country Gentleman, with scenes of a more bucolic nature.

[You can view Helck’s rustic scenes here, or visit Art.com to purchase.]

During his life, Helck described himself as an “auto addict” and wrote two books on racing—“The Checkered Flag” in 1961 and “Great Auto Races” in 1976—in addition to numerous magazine articles on the topic.

by A. Stanley Kramer

Illustration by Peter Helck

Click image to enlarge.

Learn more about the life and works of Peter Helck at Peter Helck, American Artist, a website maintained by the artist’s son and grandson.