The A-Rod Factor: Cheating in America’s Favorite Pastime

No one set out to make baseball the great national metaphor. It was just a game that involved a bat and a ball, played under a variety of rules and names, like “rounders,” “base,” or even “four-old-cat.” By 1828, it was being called “baseball” in newspapers, and by the 1840s there were league games in New England. It was played up to, and through, the Civil War. With the fighting ended, men who had learned the game while in uniform took it home with them, and its popularity grew throughout the states.

The growth of baseball was a welcome sign after the war. Americans yearned for indications that the nation was reuniting. They were encouraged by the growing number of baseball clubs, playing with roughly the same rules, that sprang up in both northern and southern states.

Even before the war, the U.S. had relatively few traditions and symbols that were valued in all states. Americans noted how European nations were united by common ancestries and ancient histories when their own country, in contrast, had an immigrant population that seemed to lack a distinctive character. And their national heritage was based on just one century of history.

Many of these same Americans looking for a national symbol thought it could be found in baseball. It seemed to reflect the principals of life in America–tough, but fair. It offered the boys and men (and sometimes ladies) who played the game a sense of achievement, cooperation, and friendly competition. And it was fun.

In 1902, the Post editors—clearly great fans of the game—were inspired to rhapsodize on the glories of baseball. “It is a manly game,” they said. And it was “a clean game. With a single exception, professional baseball has never been found to be dishonest.”

That single exception, they wrote, occurred in 1877, when players in the National League were “found guilty of throwing games.” They were expelled and have never since been permitted to play in or against a regularly organized team.” (They might have been referring to two St. Louis players, who gamblers had identified as their accomplices in a racket of throwing games.)

“The expulsion of the players above referred to took place,” the editorial continued, “and, with this, gambling became almost unknown in connection with baseball.”

“There is no use in blinking at the fact that at that time the game was thought, by solid, respectable people, to be only one degree above grand larceny, arson and mayhem, and those who engaged in it were beneath the notice of decent society.”

Source: Library of Congress

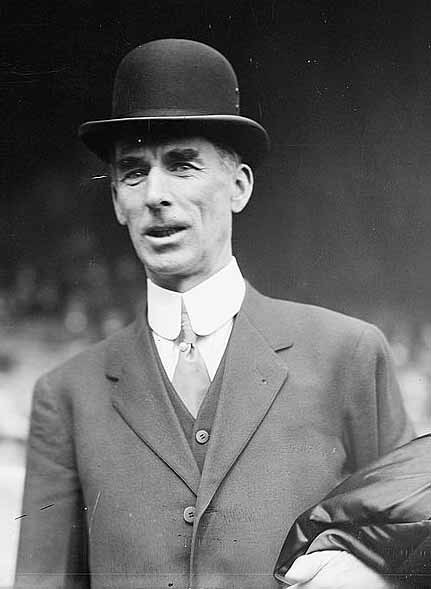

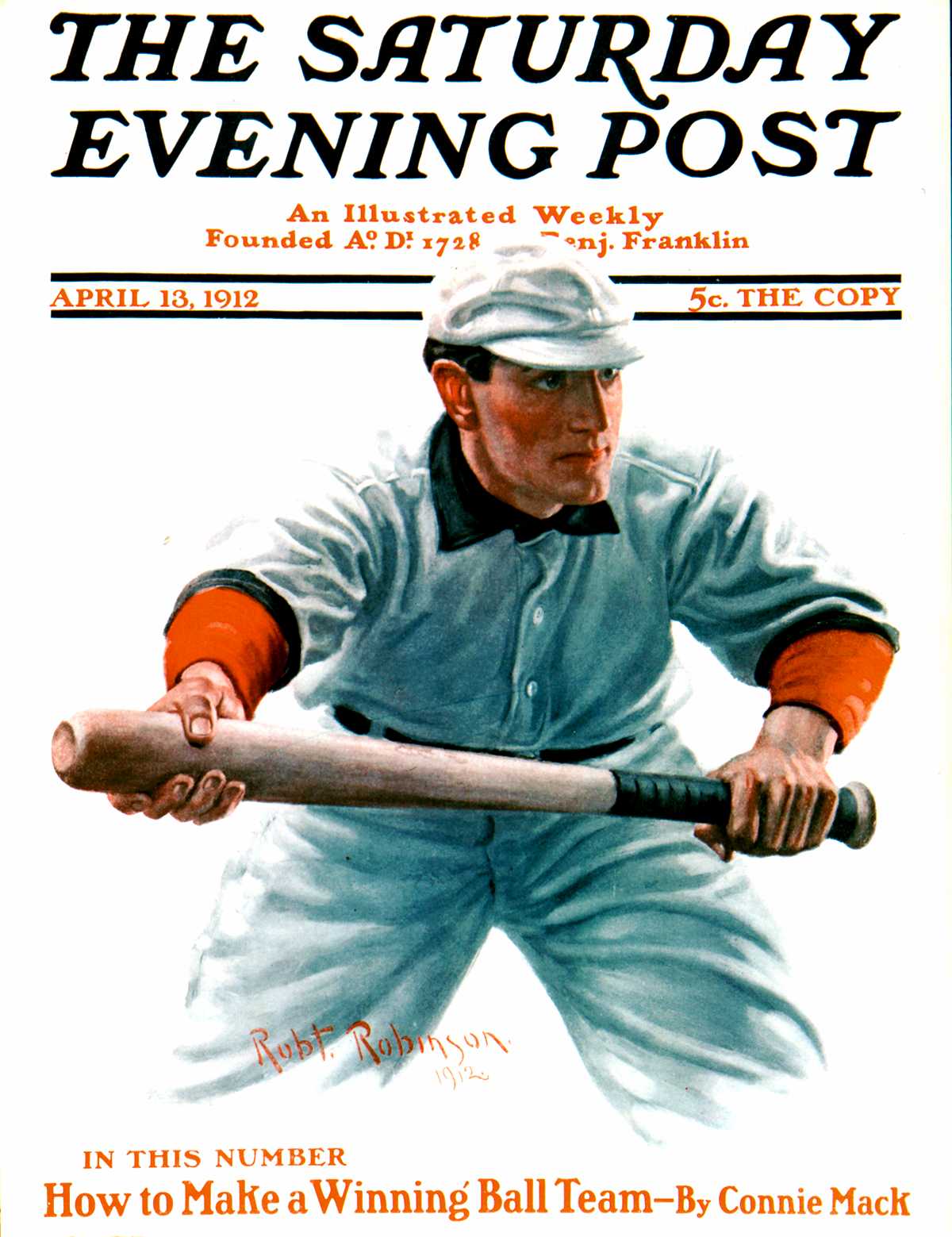

So said the Post’s editors. But that’s not the way Cornelius McGillicuddy heard it. The man who later became known as Connie Mack, the widely respected manager of the Philadelphia Athletics, started his career as a ball player in Connecticut. And this is how he remembered that ‘clean’ game:

“There is no use in blinking at the fact that at that time the game was thought, by solid, respectable people, to be only one degree above grand larceny, arson and mayhem, and those who engaged in it were beneath the notice of decent society.

The late A. G. Spalding estimated that about 5 per cent of the players were crooks in the early days of professional ball. To quote Spalding: ‘Not an important game was played on any grounds where pools on the game were not sold. A few players became so corrupt that nobody could be certain whether the issue of any game in which they participated would be determined on its merits.’

Liquor selling, either on the grounds or in close proximity thereto, was so general as to make scenes of drunkenness and riot everyday occurrences, not only among spectators but now and then among the players themselves. Almost every team had its ‘gushers,’ and a game whose spectators consisted for the most part of gamblers, rowdies, and their natural associates could not attract honest men or decent women to its exhibitions.”

All this was unknown, forgotten, or ignored by the Post’s editors in the 1900s. In a 1908 editorial, for example, they broadly claimed that baseball represented the highest ideals of the nation—“our one, perfect institution.” It was “above reproach and beyond criticism…one comparatively perfect flower of our sadly defective civilization—the only important institution, so far as we remember, which the United States regards with a practically universal, critical, unadulterated affection.”

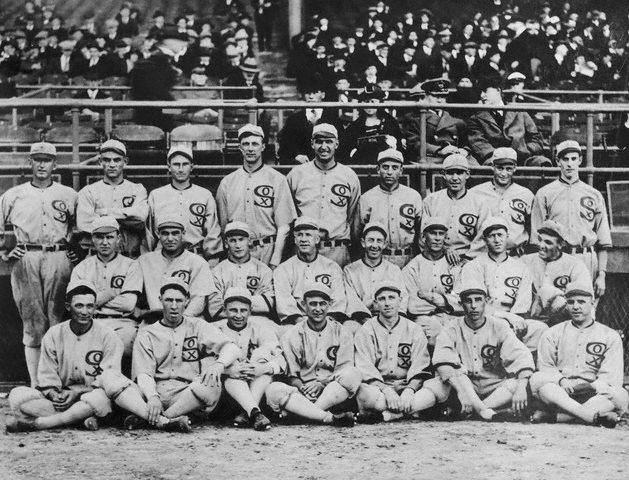

But just more than a decade later, the country learned that several players on the Chicago White Sox roster had conspired with gamblers to throw the World Series. The nation was stunned. Baseball fans might claim that players or umpires were throwing a game; it was the birthright of anyone who supported a losing team. But news of an actual conspiracy, by several players, to throw not just one game but the World Series, was outrageous.

Recalling those times in 1938, sports writer John Lardner wrote in the Post, “It nearly wrecked baseball for all eternity… It touched off a rash of scandal rumors that spread across the face of the game like measles. A hundred players and half a dozen ball clubs were involved in stories of sister plots. Baseball was said to be crooked as sin from top to bottom.

And people didn’t take their baseball lightly in those days. They threw themselves wholeheartedly into the game when World War I ended, so much so that the sudden pull-up, the revelation of crookedness, was a real and ugly shock. It got under their skins. You heard of no lynchings, but Buck Herzog, the old Giant infielder, on an exhibition tour of the West in the late Fall of 1920, was slashed with a knife by an unidentified fan who yelled: “That’s for you, you crooked such-and-such.” Buck’s name had been mentioned by error in a newspaper rumor of a minor unpleasantness in New York…[He was] as innocent as a newborn pigeon, but rumors were rumors, and the national temper was high.

It’s a fact that some of the White Sox, after the scandal hearings, were unwilling to leave the courtroom for fear of mobs.

That anger at the game’s betrayal was seen recently when a ballplayer was charged with long-time abuse of performance-enhancing drugs. Some fans were outraged, and called for brutal punishment of the offender. Other fans merely shrugged their shoulders and accepted the fact that cheating was an ineradicable part of the game.

Corruption will always be a possible factor in the game. Even the Post’s 1902 editorial, while praising the purity of the game, recognized “the instant a sport reaches the professional stage it is beset by temptations which appeal to avarice, and must then begin a constant struggle to preserve its integrity and true sporting spirit.”

The struggle continues, with the suspension of Alex Rodriguez today and, no doubt, with future investigations, scandals, and penalties in the future. There will always be people looking to cheat at professional baseball, enriching themselves and impoverishing the game. And there will always be officials and players who work at stopping them and protecting the value of the game. It is this endless contest of corruption and restoration that makes professional baseball a true symbol of the United States.

Reveling in the Past of America’s Favorite Pastime

When Major League Baseball’s All Stars take the field in July at Busch Stadium in St. Louis, thousands of fans will be thinking of Mel Ott and Eddie Joost instead of Derek Jeter and Albert Pujols. They’re keepers of the flame for teams alive only in sports history books and their own memories.

The New York Giants, Washington Senators, Boston Braves, St. Louis Browns—thousands of diamond enthusiasts still hold allegiance to these bygone teams. They organize fan clubs, celebrate great moments at meetings, and swap items on eBay every day all in the name of honoring the past of America’s pastime.

And their own youths.

Ron Gabriel grew up two miles from Ebbets Field, home of the Brooklyn Dodgers, at a time when you could hear radio announcer “Red” Barber’s play-by-play “from every open window in Brooklyn,” he recalls. These days Gabriel lives in Chevy Chase, Maryland, but Brooklyn never quite left the boy. On October 4, 1975, at 3:44 p.m., he formed the Brooklyn Dodgers Fan Club. It was 20 years to the minute of the team’s first and only World Series victory.

“I realized this intensity needed someone to bring [Dodgers fans] all together, to kind of act as a clearinghouse. I was confident I could do that.”

Gabriel hosted annual meetings at his home (serving hot dogs and Schaefer Beer, a longtime Dodgers’ sponsor). When the 50th anniversary of the team’s World Series victory rolled around in 2005, he organized a commemorative dinner and passed out bumper stickers: We Loved the Brooklyn Dodgers — and we still do!!

But for Gabriel and thousands of fans of Dem Bums, the world changed when the team moved to Los Angeles beginning with the 1958 season. “I went into a state of shock,

and I still am, still can’t believe it.” Diehards were devastated and many, like Gabriel, never transferred their allegiance to another team. “Once a Brooklyn fan, always a Brooklyn fan,” he says.

There is a common thread that binds fans of defunct teams, a certain poetry in their recollections that are valentines to the boys of summers past. You can hear it in the way they share stories —always in the present tense. Bobby Thompson hits the “shot heard round the world,” Willie Mays makes his magical over-the-shoulder catch. With each retelling, there are new insights, a deeper understanding. The drama of the game continues to unfold. Instant replays, never distant replays.

“We’re in the Twilight Zone,” says Bill Kent, founder of the New York Baseball Giants Nostalgia Society. “To us, the old Giants are still alive. We relive their exploits.”

Kent grew up in the Bronx, a trolley and subway ride away from the old Polo Grounds in upper Manhattan. As a youngster, Kent would sometimes sneak into the ballpark by climbing over the fence before crews arrived and stake out empty seats with his friends. Other times, he’d get picked to turn the turnstiles at the entrance gate, earning spare change and free admission to the game. It was a highly coveted role. “There were always more kids than jobs.”

The Giants society is a loosely knit group of baseball fans, lawyers, teachers, sports writers, and even “a lady umpire and a lady baseball player” among them, who participate in an online discussion group and get together three times a year for what Kent calls schmoozing. Three or four people showed up at the first meeting held at a Chinese restaurant. Word spread, and Kent had to find larger quarters at an Italian restaurant. These days, meetings attract upwards of 50 and are often held in a church basement. Ten dollars pays for the pizza. There are even a couple of Dodgers fans and a sprinkling of Mets fans. “We don’t care. We have nice people, and if they’re not nice, they’re out,” he says.

The 1950s was a turbulent decade for baseball fans. In 1953, the St. Louis Browns played their last game at Sportsman’s Park before moving to Baltimore. Brownies pitcher Ned Garver, who won 20 games for the 1951 team that ended with a 52-102 record, once famously said: “Our fans never booed us. They wouldn’t dare. We outnumbered ’em.” At least their legacy is alive and well. The St. Louis Browns Historical Society and Fan Club is celebrating its 25th anniversary this year.

In 1954, the Philadelphia Athletics moved to Kansas City; in 1953 the Boston Braves moved to Milwaukee. And, of course, there was the twin sting for New Yorkers in 1958 when both the Dodgers and Giants made their way to California.

When the Philadelphia Athletics moved to Kansas City starting with the 1955 season, it wasn’t a surprise. But that didn’t make it any easier for fans like Dave Jordan. “For a couple of years it was clear the A’s were running out of money,” he says. The city couldn’t support both the A’s and the Philadelphia Phillies. Still, Jordan says when the mayor announced a “Save the A’s” committee, “I was one of few people who took him seriously.”

Jordan is chairman of the board of the Philadelphia Athletics Historical Society in Hatboro, Pennsylvania, a robust organization of 800 members spread coast to coast. The society puts out a bimonthly newsletter, runs a museum, and holds functions to which original players are invited. There are a few younger members, but Jordan says that for the most part, its ranks are filled with people who were Shibe Park regulars in the days of Lefty Grove, Jimmie Foxx, Eddie Collins, and Mickey Cochrane. One of Jordan’s favorite ballpark memories was the 24-inning game against the Detroit Tigers on July 21, 1945, called due to darkness.

“I kept score for 22 innings until I ran out of space.” He donated that incomplete scorecard to the Philadelphia A’s Society Museum and Library.

When the team moved on to Kansas City, Jordan stayed a fan. “In 1955 and 1956 I went to Yankee Stadium when Kansas City was in town, but it wasn’t the same. They changed the numbers of quite a few players, and eventually I had to face the fact that the Phillies were what we had left.”

Middle-aged fans are now golden agers and elder statesmen. “That’s something we at the society think about,” Jordan says. “Until recently, we always had a big breakfast in the fall, selling out with hundreds of fans showing up.” But, he says, as volunteers get older, functions are being scaled back.

There are also fewer players alive who wore the uniform.

The repercussions are showing up in the sports memorabilia market. Mike Heffner, president of Lelands.com, the oldest and one of the largest sports memorabilia auction houses, says the 1980s and ’90s were the boom days in memorabilia of defunct teams. “In the past few years, we’ve noticed a slowdown. People who were following teams in the 1940s and ’50s are mostly retired, some have passed away, and their collections have been sold.”

Some team items are valuable not because of the passion of their fans but because of their scarcity. The Seattle Pilots, for instance, played one year in 1969 before becoming the Milwaukee Brewers. “They didn’t have a huge fan base. There aren’t a tremendous

amount of them out there. But a uniform patch or a team-signed ball is very rare, so it’s tremendously collectible,” Heffner says. The Colt .45s (1962-1964), a squad that became the Astros, “were a terrible team, but they had really neat uniforms with a pistol on the front, so they’re highly collectible.” The latest franchise to join the brotherhood of bygone teams is the Montreal Expos, now the Washington Nationals. But don’t look for big returns there. “Canada and baseball don’t go together that well,” Heffner says.

Of course, for fans it’s not about money and not even about memorabilia. Their teams may not be in the box scores, and the ballparks may long be gone, but the boys of summer never grow old.