Considering History: Post-9/11 Lessons from America’s Forgotten War in the Philippines

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

The effects of the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks have defined much of American society over the subsequent two decades. From the creation of new government agencies like the TSA and the Department of Homeland Security (and within it the increasingly visible ICE) to the rise of a ubiquitous surveillance state to countless pop culture texts, 9/11’s influences have been both broad and deep. One of the most significant such effects was also one of the first: the war in Afghanistan, which began on October 7, 2001 as a focused mission to find those responsible for the attacks but evolved into America’s longest war, passing Vietnam for that title in 2010.

Yet while the conflicts in Afghanistan and Vietnam are indeed two of America’s longest foreign wars, there’s another, far less well-remembered contender for that title: the late 19th and early 20th century war of occupation in the Philippines. That controversial war deserves far more of a presence in our collective memories, for its own sake but also for the lessons it can impart about post-9/11 America.

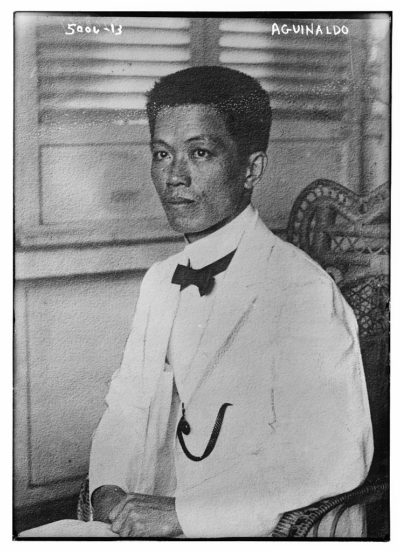

The Philippine-American War emerged directly out of the 1898-99 Spanish-American War, a somewhat more familiar conflict that would likewise be importantly reframed by the war that followed it. After all, the U.S. victory in the Philippines in the Spanish-American War depended on Filipino anti-Spanish revolutionaries, a longstanding group of independence fighters led by the charismatic exile Emilio Aguinaldo y Famy. Much like the CIA worked with the mujahideen (direct predecessors to Al Qaeda and the Taliban) in Afghanistan against the Soviets, the U.S. capitalized on these anti-imperial forces in their opposition to the Spanish in the Philippines.

But Aguinaldo and his fellow revolutionaries had their own goals for their country, ones that preceded U.S. involvement, and they began pursuing them even while the Spanish-American War was still unfolding. After Aguinaldo and his forces defeated the Spanish at the May 1898 Battle of Alapan, he raised for the first time a Filipino flag (sewn in Hong Kong during Aguinaldo’s time in exile there). A few weeks later, Aguinaldo issued a Declaration of Philippine Independence and named himself the first President of the Philippine Republic. The U.S. government refused to acknowledge either those actions or that independent nation, however, setting up an extended conflict once their wartime need for Aguinaldo and his forces ended.

In January 1899, as the Spanish-American War neared its conclusion, President McKinley created a commission (known both as the First Philippine Commission and the Schurman Commission) to investigate conditions in the Philippines and make a recommendation about both the nation’s future and the U.S. role there. But given that the five-member commission featured both Admiral George Dewey (one of the war’s military leaders) and Elwell Otis (the U.S. Military Governor of the Philippines), its conclusions seemed preordained. And indeed, the Schurman Commission came to the conclusion that Filipinos were not ready for independence or self-governance and needed further U.S. presence in the islands to pursue those ends, a perspective that echoes closely the “bringing democracy to the world” narrative that fueled the post-9/11 wars in both Afghanistan and Iraq.

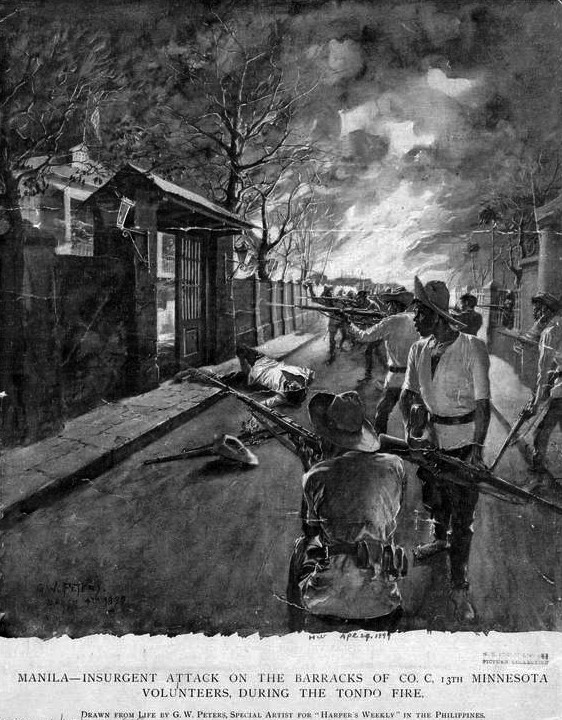

This evolving narrative of the U.S. presence in the islands meant that when the Spanish-American War’s official purpose (liberating the Philippines from Spanish rule) had been achieved, a second, far more extended and bloody war between local forces and occupying U.S. troops commenced. That second conflict began even before the Treaty of Paris between the U.S. and Spain took effect, with the first shots fired between Filipino insurgents and U.S. forces on February 4, 1899 (in what came to be known as the First Battle of Manila), two days before that peace treaty was signed. Many of those Filipino insurgents, like their leader Aguinaldo, had been U.S. allies throughout the war. But just as was the case in Afghanistan and Iraq, as the U.S. forces’ purpose evolved from liberation to occupation, these rebels became obstacles to that ongoing mission.

Thus as was the case in Afghanistan and Iraq, and in Vietnam before them, this became a war of occupation and insurgency, a conflict in which every Filipino was potentially an adversary or at least involved in aiding the revolutionaries fighting against the U.S. forces. That fraught fact meant that every encounter between U.S. troops and Filipino citizens was shadowed by this ongoing conflict, and it concurrently led the U.S. occupying forces to treat all Filipinos as hostile, with destructive effects on both the collective level (such as the destruction of villages) and the individual one (such as the use of torture on perceived enemy combatants, including waterboarding). All of which only pushed more and more Filipinos toward the insurgent cause and reinforced the U.S. as an occupying force in the islands (rather than a liberating presence or a force for democracy).

All those factors contributed to a long, violent conflict between U.S. forces and insurgents. The Philippine-American War officially ended in 1902, but that was just because Aguinaldo had been captured in March 1901 and his allies gradually surrendered over the subsequent months; more than 4,000 U.S. soldiers and more than 20,000 Filipino combatants (and hundreds of thousands of Filipino civilians) died in these first three years of conflict. Filipino insurgents continued fighting U.S. forces in what came to be known as the Moro Rebellion for another decade, only surrendering in 1913. This 15-year war offers vital lessons about what it means to be an occupying force, how a history of realpolitik relationships with revolutionaries can lead to future entanglements, and how a seemingly straightforward military objective can shift through a combination of idealistic and imperialistic factors into a brutal war of occupation and insurgency.

But there are additional lessons from this forgotten long war that are perhaps even more salient for 2019 America. Because of the U.S. occupation, many Filipinos immigrated to America, building on what was already the nation’s oldest Asian-American community but greatly amplifying it in the first decades of the 20th century. These Filipino Americans became hugely significant to every aspect of American society: contributing to the military, like the first Filipino West Point graduate and World War I and World War II hero General Vicente Lim; to civic life, like Agripino Jaucian and the Filipino American Association of Philadelphia, which offered vital medical treatment during the 1918 influenza epidemic; and to activist efforts, like Pablo Manlapit and the ground-breaking Filipino Labor Union in Hawaii.

But this expanding early 20th century Filipino-American community also faced white supremacist xenophobia and prejudice. They were the target of hate crimes and racial terrorism, such as the Watsonville, California “riots” of 1930 in which an entire Filipino-American neighborhood was destroyed. And they were the subject of multiple national exclusionary laws: first redefined as legal “aliens” by the 1934 Tydings-McDuffie Act despite the U.S. occupation of their nation (ironically, the law granted the Philippines eventual independence in order to make that redefinition possible); and then subject to an overt campaign to forcibly remove all 120,000 Filipino Americans back to the Philippines with the 1935 Filipino Repatriation Act.

In 2019, we see many of those same histories playing out when it comes to Arab and Muslim Americans: hate crimes are once more on the rise (as they were in the years after 9/11) against these longstanding American communities; and legal attempts to restrict Muslim immigration are taking place, including ones targeting wartime allies like Afghan and Iraqi military interpreters. These recent events provide one more reason to better remember the histories and legacies of the forgotten Philippine-American War, and to heed the lessons it offers for post-9/11 America.

Featured image: Philippine insurgent soldiers, 1899 (U.S. Army Signal Corps via Wikimedia Commons)