Coles Phillips

Clarence (C.) Coles Phillips’s hallmark style is one that won’t ever fade away. A mid-westerner born in Springfield, Ohio, Phillips spent the entirety of his childhood in Ohio before moving to New York City. Arriving in the big city, Phillips immediately began defining the era of “The Golden Age of Illustration” with advertisements and magazine illustrations of beautiful women blended into fanciful backgrounds.

Phillips’s interest in art and design began at a very young age; he started drawing at just 6 years old. He attended the liberal arts university Kenyon College from 1902-1904 where he was the head illustrator for the yearbook, The Reveille, while working at the nearby offices of the American Radiator Company.

At Kenyon, Coles was an active member of Alpha Delta Phi fraternity. His fraternity brothers gave him the nickname “Psi”, a name that stuck for the rest of his life. The brothers heavily influenced his decision to drop out of school and move to New York. Many had secured lucrative positions on Wall Street, where the fraternal cohort encouraged Phillips to join them as a roommate. So he did. Phillips left Kenyon in the middle of his junior year; he never completed his college education.

Covers by Coles Phillips

Bathing Beauty and Rain

Coles Phillips

September 4, 1920

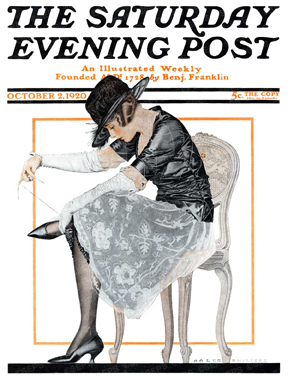

Mending Her Stockings

Coles Phillips

October 2, 1920

Novice Golfer

Coles Phillips

November 18, 1922

He quickly used his prior contacts at the American Radiator Company to attain a position at the company offices in Manhattan. He enrolled in night courses at the Chase School of Art for a short stint of three months. The classes were Phillips’s only formal art training.

Phillips rose to artistic prominence quickly due to a series of fortunate events. After having finished his art classes, he joined an “assembly-line” advertising firm to gain experience producing commercial content. One artist painted a person’s head, another their clothes, and Phillips the ankles and feet. His depictions of human feet were so meticulous that national companies asked the identity of the man who illustrated them.

Just 2 years into his career as an artist, in 1906, the artist opened his own advertising and design firm called The C. C. Phillips & Co. Agency. He thought the entrepreneurial endeavor would provide him the opportunity to be his own boss, and to choose his clientele. The new company did just that, but at great cost to the artist’s personal happiness.

Business poured in for the new operation, but the shop was so busy Phillips took on a purely managerial role. He held meetings with clients and worked on sketches, completing few illustrations himself. His trusted team of underling artists, including Edward Hopper (who Phillips hired personally), created all the works. The firm produced advertisements for many major American corporations of the time including Holeproof Hosiery, Palmolive, Willy’s Overland Auto & Trucks, Vitralite Paint, Scranton Lace, National Mazda Lamps, Jantzen Swimsuits, Oneida Community Silver, Motor Annual, Maxwell Phillips, Auto-Lite, and Luxite.

Rare is the man whose unhappiness results from building a successful business. Psi Phillips, though, was a passionate artist. He left the business he built to instead return to freelance illustration. In 1907, he rented a studio in Manhattan at 13 West 29th Street. He received his first commission for a black and white centerfold illustration from Life (not to be confused with the famous photography magazine) Magazine for their April 11th, 1907 issue. Life Magazine was in a design predicament as it moved to color printings during the spring of 1908. Phillips introduced Life to his now infamous “Fadeaway” style. The artwork was a hit for both Life and Phillips’s career. Many tried to replicate his style, but advertisers, magazines, and literary agents wanted the real deal.

In 1907, he also met his future wife, Teresa Hyde, who at the time worked as a nurse. The two married three years later in 1910. Over many years, the two built a sizeable family complete with four sons. Seeing as Manhattan’s shoebox apartments were far too small for such a litter, the couple relocated to a home in the artist colony of New Rochelle, Connecticut.

Over the course of the next decade, Phillips’s style ushered in a new era of art, culture, fashion, and design. His work took the United States from the Edwardian Era and brought it into the Roaring Twenties. He produced work for advertisements, books, stamps, magazines, posters, calendars, streetcar signs, prints, and silverware. He created 62 covers for Good Housekeeping, 70 for Life Magazine, and countless others for Vogue, Collier’s, Liberty, McCall’s, Ladies’ Home Journal, Women’s Home Companion, and of course from 1920-1923, The Saturday Evening Post.

His artwork generated vast personal wealth the artist used to enjoy his life in the countryside. Coles once stated that his favorite activities were painting, pigeon farming (raised and sold over 30,000 annually), singing in the University Glee Club of New York with his fraternity brothers, and playing baseball with his boys.

Unfortunately, his life was cut short by tuberculosis of the kidney. Diagnosed in 1924, he spent the next three years searching out European sanitarium treatment options. The family lived in Switzerland and Italy from 1925 to 1926 before returning to New Rochelle in 1927. Phillips spent the day of his death in bed with his wife by his side while friend and colleague J.C. Leyendecker took his four sons to the Charles Lindbergh Parade on 5th Avenue. He died at age 47 of respiratory failure.

Coles Phillips is now recognized as the singular artist of his generation who invented the popular “fade away” style. His models brought an elegant grace to the twentieth century’s rising tide of wealth and parties. As such, The Society of Illustrators inducted Phillips into their Hall of Fame in 1993. Today, many of his original illustrations are on display in the Delaware Museum of Art.