He Saw the War Coming

The 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor wasn’t a complete surprise to all Americans. Some had long anticipated a Japanese offensive against the U.S. and had foreseen, with surprising clarity, the general direction of the war. One of them was Fletcher Pratt, a writer of science fiction, a pioneer in war gaming, and “one of the outstanding lay military and naval authorities in the United States,” as the Post described him in its Keeping Posted column.

Just as the war in Europe began in 1939, Pratt completed a book on the world’s naval forces and strategy. An excerpt offering his opinion of the current U.S. Navy was published in the Post that year in its October 7 issue. (Read Pratt’s entire article “Columbia, the Gem of the Ocean” from the Post here.)

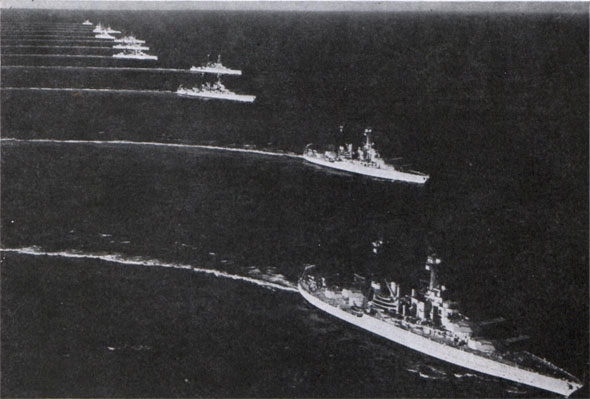

It didn’t sound good. “The battle line is the slowest in the world, which is to say that it cannot force an unwilling enemy to fight, nor escape from a disastrously superior one. Some of the battleships steer badly. The early heavy cruisers vibrate rackingly at high speeds, roll in a seaway and have weak features in their construction.”

Official U.S. Navy Photographs-Courtesy U.S. Navy Recruiting Bureau

“Promotion in the American Navy is desperately slow and uncertain,” Pratt added. “Junior officers are constantly tempted to toady, and examining boards to give credit for correct routine rather than for original thought. Officers reach command rank late in life. … In no country does it take longer to sign a contract for a new ship; in none is the building process marked by so many petty squabbles.”

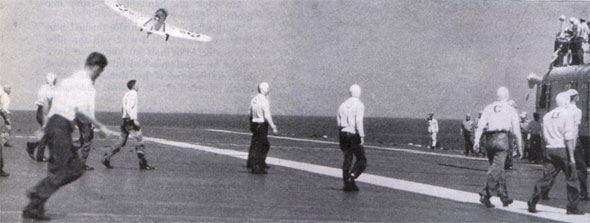

Yet he concluded, “No navy in existence, hardly any two together, can bear the weight of the United States fleet.” Its battleships were slow, he wrote, but they were well armed, and its aircraft carriers were the envy of the world. “The American naval air service is a model which other nations have despairingly been trying to equal for 15 years. No navy has so good a catapult; the bomb sight has for years been the object of affectionate curiosity on the part of half the spies in the world.”

Pratt compared the U.S. Navy with its most likely opponent — not Nazi Germany, who many Americans feared they’d soon be fighting — but Imperial Japan.

In general, Pratt didn’t think Japan’s navy was much of a threat. While “the whole American battle line is up to date today, most of the Japanese line well on the march toward the scrap heap.”

The Japanese fleet, Pratt said, “lacks gun power and armor to stand against the American giants. The operating range of the whole Japanese fleet is something under 2,500 miles. … A Japanese campaign against the United States [is] simply impossible as long as American warships float in Pearl Harbor.”

Over the years, I’ve read predictions by several journalists of the past. None of them got everything right. But some predictions stand out for being right about the important points. The important point of Pratt’s report is that, from two years away, he saw the challenges the Allies would face in 1941.

According to Pratt, the British navy was “very poorly fitted for South Sea work; it is composed of World War [I] battleships with the short ranges, good protection against cold and bad protection against heat.” The Japanese would pounce on a moment of British vulnerability to strike, very likely seizing “the Dutch East Indies — those vast storehouses of every raw material the island empire needs.”

Which is precisely what Japan did, just one day after their assault on Pearl Harbor.

Foreseeing an inevitable conflict between American and Japanese forces in the Pacific, Pratt predicted the Japanese offensive would focus on “direct conquest of American establishments west of Hawaii. Guam, Wake, Midway, the Philippines, all the small American outposts, would fall in the first rush.”

All these islands were attacked. All but Midway were taken by early 1942.

Official U.S. Navy Photographs-Courtesy U.S. Navy Recruiting

America’s offensive against Japan, Pratt wrote, would have to come up from the southern Pacific. The northern route, down from Seattle or Alaska, was too long and wouldn’t affect any of Japan’s interest.

So the U.S. would have to start from Hawaii, Pratt wrote, and proceed to the Marshall and Caroline Islands to connect with Australian forces, then “roll up the Japanese lines from the south. Once that circuit were accomplished, once that blockade set up, Japan would be cut off; she must surrender or die — of a lack of food, oil, and iron, not to mention the many less essential materials she does not have in the islands. Japanese strategy and naval construction are accordingly directed toward the prevention of such a blockade.”

Overall, a fairly accurate synopsis of what took place in the Pacific between 1941 and 1945. True, the Caroline Islands weren’t part of the U.S. offensive. American troops advanced on Japan through the Marshall to the Mariana Islands, while a southern initiative led from the Solomons through New Guinea, all heading toward the Philippines.

Such differences are minor, considering that Pratt was a journalist. He was not a naval officer and had no access to the military’s intelligence reports. Just as remarkable, was his ability to perceive the future at a time when fears and resentments kept many Americans from clearly seeing the situation right before them.

October 7, 1939

Step into 1939 with a peek at these pages from The Saturday Evening Post 75 years ago: