The Laziest Musical Instrument in the World

You’re an ambitious hostess in a turn-of-the-century, middle-class home. Your dinner guests have finished their mutton pies and cream pudding and they’re bouncing off the papered walls from the café noir. You’d planned to keep them entertained with some trendy parlor games, but charades isn’t going to cut it for this crowd. They need music, a group sing-along of “Sweet Adeline” or “Wait Till the Sun Shines Nellie,” but there isn’t a pianist in the bunch.

What’s a dilettante to do?

Enter the player piano. For the first time in history, attractive music filled homes without the need for a learned (human) player. With a steady pump of the foot pedals, or treadles, your piano could play itself, the black and white keys moving as if fingered by a poltergeist. Your dinner guests have a grand time and the party is saved, thanks to pneumatic technology.

Though the player piano is understood now as an obsolete oddity — a short-lived steampunk quirk of simpler times — the instrument was a revolutionary step forward for bringing music into new places at the dawn of the 20th century. Piano rolls, the perforated “code” of the player piano, also remain as unique historical record of the stylings of iconic pianists of the period.

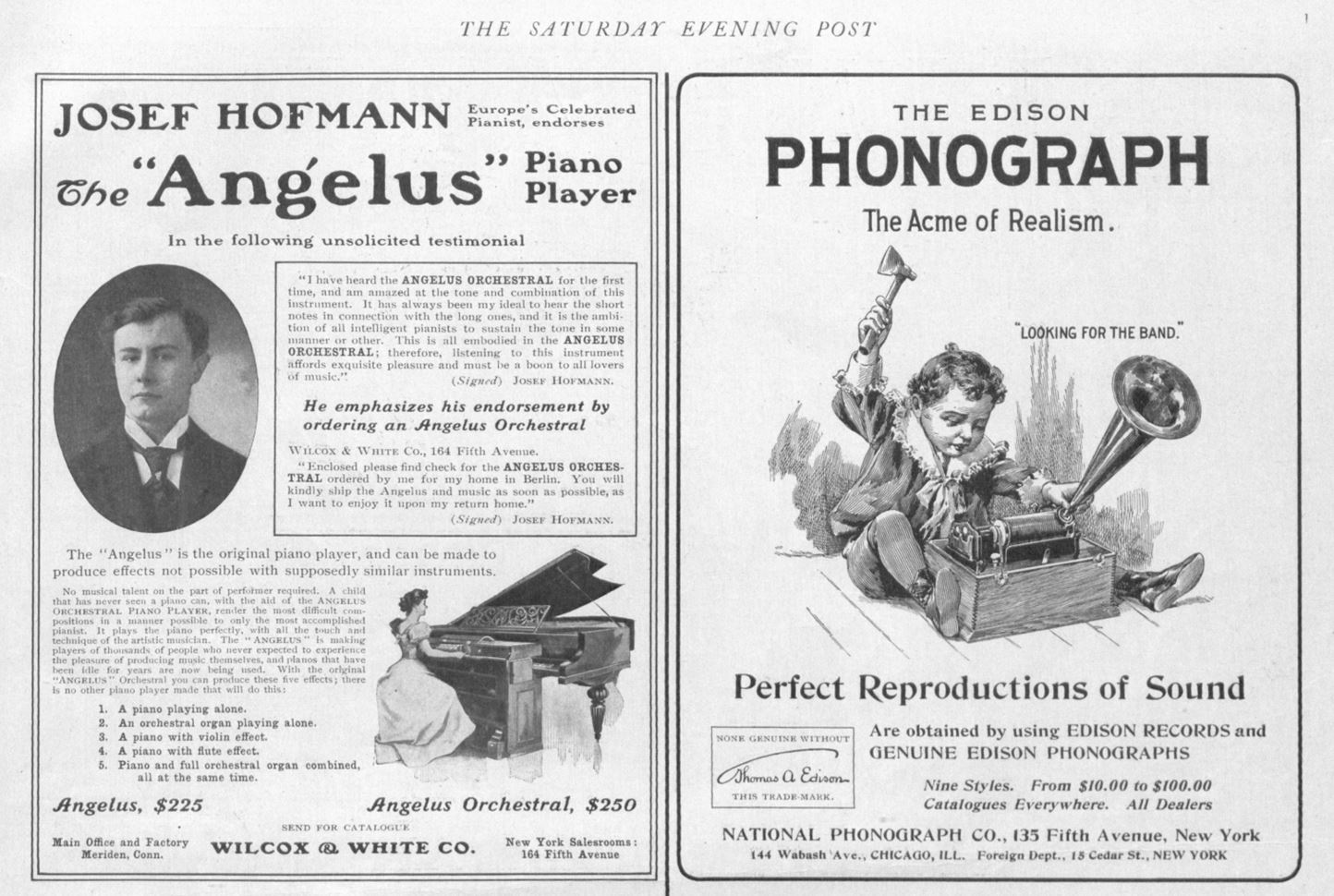

In 1901, piano manufacturers began advertising a contradictory claim in this magazine to anyone who ever longed for marches and ragtime music in their very own abode. The promise was that even the least practiced musical amateur could turn out perfect tunes with their new technology. At once, companies like Wilcox & White or The Cable Company insisted that there was “no musical talent on the part of the performer required” and yet “it enables you to play with the interpretation of the composer.”

So, which was it?

In reality, the operator did little more than power the musical device, adjusting its speed, as it rendered tunes from piano rolls in full splendor on the piano. It was live music — technically — but the “pianist” needn’t know the first thing about how to play. Before radios and record players increased music access to every corner of the country, the player piano brought professional music to consumers for a steeper price ($250 in 1905, equivalent to about $7,300 in 2019).

The first automated piano players were not the built-in models that instrument enthusiasts readily recognize today. They were an entirely separate piece of furniture, like the Angelus Orchestral, that the operator placed before their piano. These piano players (as opposed to player pianos) were developed and sold in the 1890s and in the first decade of the 1900s, and they played 65 keys instead of the full 88. Sitting behind the piano player and pressing a foot pedal or turning a crank would apply pressure to a bellows that runs a pneumatic motor — not unlike the early vacuum cleaners of the 19th century — and felt-tipped rods would strike down on the keys in accordance with the rolling paper guide.

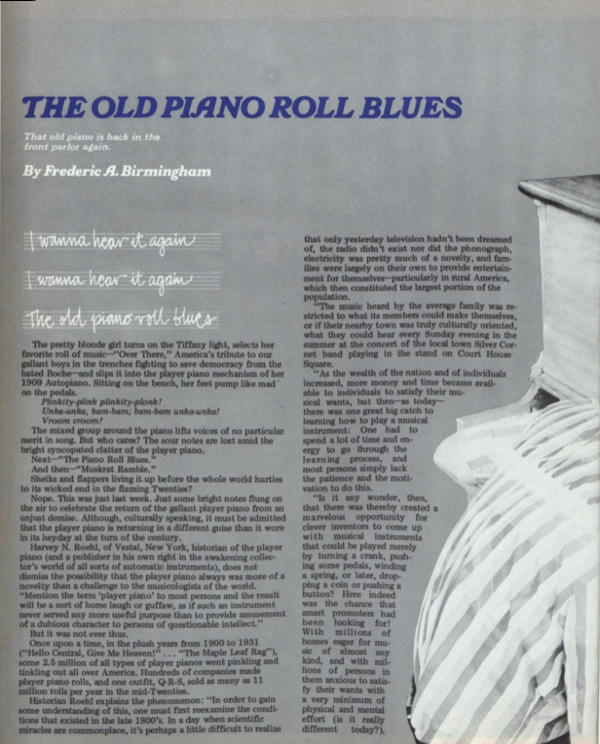

Within a few years, manufacturers were moving the player mechanism into the piano, and the resulting streamlined instrument became more marketable. Historian Harvey Roehl said in this magazine in 1975, “As the wealth of the nation and of individuals increased, more money and time became available to individuals to satisfy their musical wants, but then — as today — there was one great big catch to learning how to play a musical instrument: One had to spend a lot of time and energy to go through the learning process, and most persons simply lack the patience and the motivation to do this.”

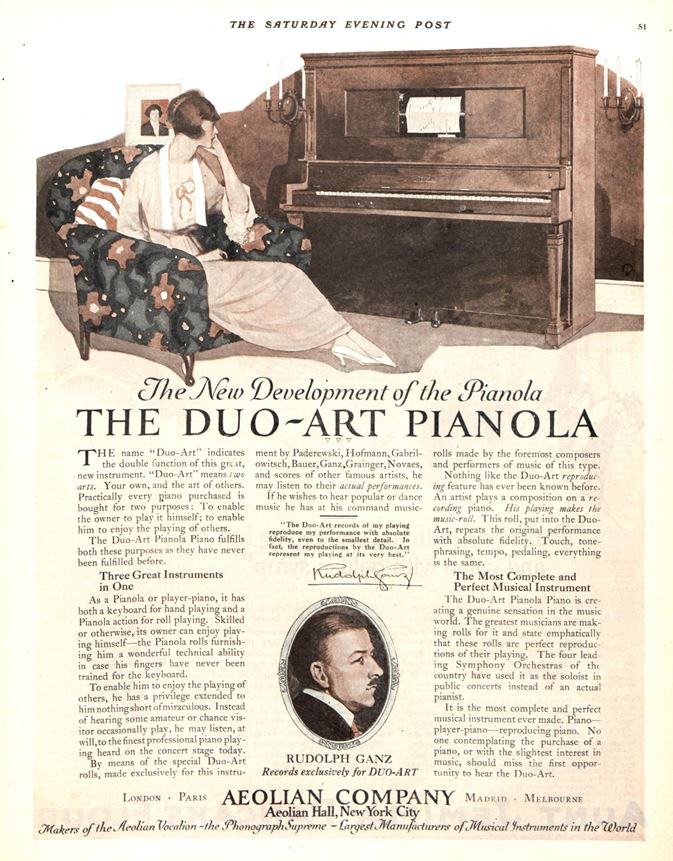

Dozens of companies began manufacturing player, or “reproducing,” pianos, but one company made its name synonymous with them: the Aeolian Company. Their product’s moniker — pianola — became interchangeable with player pianos in the years leading up to the first World War. In 1909, Aeolian claimed they had fought 17 infringements on their precious trademark, what Joseph Fox in American Heritage called “a piano and something more … a musical word for a musical object: quite perfect.”

Player pianos — especially the pianola — held full-page, color ads in the teens and twenties promising to “give your brains a holiday” or “hear Paderewski play his famous minuet” or even to aid in teaching your children music. Depending on who you asked, the mechanical piano was either a dismal metaphor for the decline of artistry or an exciting tool for democratizing the classics.

In Laurel and Hardy’s The Music Box (1932), the bumbling pair struggle to deliver a piano to a second-floor apartment, battling stairs, pulleys, and an unfortunately-located water feature. When they finally get the instrument to its rightful room, they discover it’s a player piano. The owner storms in, declares “they are mechanical blunderbusses!” and takes an axe to it, pausing to salute, of course, when the piano starts rolling the national anthem. In 1952, Kurt Vonnegut’s first novel, Player Piano, depicted the machine as a symbol of automation and dehumanization in an increasingly industrialized world.

It wasn’t only an apparatus for the unartistic, though. For some, the player piano gave way to a new kind of art: crafting impossible compositions.

Among the European creative scene in the 1920s that included James Joyce, Igor Stravinsky, Pablo Picasso, and Ernest Hemingway, New Jerseyan George Antheil gained a reputation as an enfant terrible of music. When he conceived his Ballet mécanique while living in an apartment above Shakespeare & Company in Paris, he called it “the first piece of music that has been composed OUT OF and FOR machines, ON EARTH.” The score called for 16 player pianos, xylophones, bass drums, a tam-tam, a siren, and three airplane propellers. Impossibly, the player pianos were all to be synchronized. Since this could only be done in theory, Anthiel settled for one player piano in live performances of his “ballet,” its keys emanating a futuristic cacophony more akin to Kraftwerk than Stravinsky. When he took his not-quite-realized performance to Carnegie Hall, the audience was nearly blown away by the propellers and he was laughed out of town.

Conlon Nancarrow, an offbeat musician and American expatriate, found the player piano in the 1930s, and he also saw it as a tool for taking his music beyond the confines of human capability. Nancarrow acquired a machine to cut his own piano rolls in the ’40s, and he used it to compose avant-garde music that defies the speed and dexterity of human hands. His compositions, like “Study for Player Piano No. 37” and “No. 40” sound like dueling pianos in some otherworldly cabaret — not exactly the kind of fodder for after-dinner sing-alongs.

As expected, most consumers weren’t using their player pianos to delve into the oeuvres of experimental sound. They wanted to keep up with popular musical trends and play ragtime and classical greats in their own home. Since the German Welte-Mignon company developed a machine that allowed pianists to record directly onto a piano roll in 1904, American companies competed fiercely to get the top performers into their offerings. Zez Confrey’s “Kitten on the Keys” was popular, as were rolls made by Percy Grainger and George Gershwin. Aeolian boasted that Josef Hofmann and Harold Bauer made rolls exclusively for the Duo-Art Pianola.

Millions of piano rolls were produced in the early century, many of which have been archived by the Stanford University Piano Roll Project. Their head librarian, Jerry McBride, says these rolls hold a unique — though controversial — significance in sound recording history. “Mahler made rolls, Camille Saint-Saëns,” he says. “There are a handful of rolls by Debussy, and these are the only recordings we have of Debussy playing his own solo piano music. That’s all we have of Debussy playing piano, which is amazing.”

One reason McBride finds them exciting is the potential to study piano-playing styles of the past. “A number of pianists who were recording at that time would have learned piano around the mid-1800s,” he says, “so we can look at these rolls to understand how piano was played in the 19th century, which is quite different than how it’s played today.” McBride notes that a surprising tendency of early century pianists was to add notes and expressions that deviated from the score, unlike the strict playing we’ve come to know. “They were much freer with their approach to interpretation than today,” he says.

The part music archivists can’t agree on is how important these rolls are in understanding piano playing of the past. On one hand, the rhythm and notes on them are precise replications, and sound recordings of the time are scratchy and low-quality. On the other hand, piano rolls can’t express tempo and dynamics of the music as precisely. These were often marked onto the roll by a bystander musician. According to the Pianola Institute, “Duo-Art rolls are more akin to portraits than to photographs, but a portrait can often be the more telling of the two.”

Still, a Rachmaninoff piano roll is sure to be more enjoyable and lively than one of his 1919 recordings with Thomas Edison.

But sound recording got better. In the 1930s, the phonograph, radio, and the Great Depression delivered death blows to the player piano, and it became a memory as quickly as it had spread throughout the nation.

The player piano never completely went away, though. In fact, you can still turn your piano into a self-playing one (for north of 2,700 dollars) if you’d like, and this time around, you can control the songs with your iPad. If, somehow, you still have a player piano that plays paper rolls, you can still buy those too, from Artie Shaw to Britney Spears. The company that produces them, QRS, has been in business since 1900, and they’re proud of their historical trade. Their website claims, “the piano roll has lasted longer than any other standard for recording and reproducing music, and an 80-year-old roll will still sound the same today as the day it was punched.”

We have progressed considerably in sound technology in 100 years, though. These days, if you find yourself with antsy houseguests, there’s no cause for alarm if you don’t have a classic Duo-Art Pianola in the parlor. Just blurt out, “Alexa, play ‘Scott Joplin’s New Rag,’” to get the party started.

Featured image: QRS advertisement from February 4, 1922 issue of The Saturday Evening Post