“Misfortune’s Isle” by Richard Matthews Hallet

Richard Matthews Hallet is best known for his sea stories, no doubt inspired from his life growing up on the Atlantic Ocean in Maine. His life of writing ocean adventures was nearly an impossibility — until his story “The Black Squad” was picked up by the Post in the early 1900s, saving his career. After his first story was published, he continued to write adventure stories for the Post, one of the best being “Misfortune’s Isle” which has since been adapted into several radio and film programs using Hallet’s Island as the location for their eerie tales.

Published on November 9, 1929

C’aptain Arad’s first glimpse of the Doha Delfina Crispo showed him a soul imprisoned. The rebellious eye, the rich mouth shadowed by black hair, the very pose of her slim body in the open carriage, were all eloquent of her captivity. She was the wife of Don Narciso Crispo, captain general of Zamboanga, but now resident in Manila — a little monkey of a man, yellow as a faded sunflower from jaundice, and with a limp acquired from a drunken fall into a tiger pit outside of Singapore. Ambitious and romantic, Doha Delfina had nothing to do but rise at eleven in the morning, take chocolate, hold her soul firm, and through a broken oyster shell in the oyster-shell window of her balcony watch the black soldiers, the cigar makers and ship captains filing past.

Half-breed women — those mestizas with the magnificent hair and the hint of China in their eye corners — could vary the monotony by leaning out occasionally to spit at a mark with betel-nut juice — say, for choice, the sombrero of a passing caballero. Dona Delfina, a woman of rank, had to content herself with French and Spanish novels, and an occasional cigar. She remained in advanced dishabille until four in the afternoon, usually. When an earthquake had moved the upper walls of the house on its beams — they stuck out four or five feet, so as to give what Arad called margin enough to veer and haul on — she had been perhaps the only woman in Manila who had not rushed into the streets beating her breast and crying, “Misericordia! Don Jorge, misericordia!” Her heart, no doubt, had stopped in her bosom, but she had only bowed her head and prayed to be engulfed, snatched bodily away from such a hateful destiny.

The satirical earthquake had contented itself with putting a queer kink into the cathedral roof, overthrowing the bull-ring parapets, and bringing down one of the eight arches of the iron bridge over the River Pasig. After that, everything was as before. The cathedral bells tolled at stated times, the clack of stone hammers beating out tobacco leaf was resumed in the tobacco factory, and at four o’clock, when the sea breeze revived, carriages in an endless chain began to revolve on the Calzada — the boulevard just outside the walls on the bay side of the town.

These carriages were called the shoes of the country — in fact, no woman of rank could walk so much as a hundred paces — and Doha Delfina’s shoe was drawn by two gray Manila ponies, one bestridden by a postilion in shiny black leggings, a spur on his left heel, tight shorts, a spicy jacket, and a hat as hard and black as a japanned-iron coal scuttle. Doha Delfina would usually be looking past this individual’s ears at the shipping in the bay. Certainly every size and shape and intention of ship was there, a quaint intermingling of chain, hemp, grass rope, coir and bamboo cables; and among these Arad’s ship, the Water Witch of Salem, was not the least conspicuous, with her black hull and painted ports, her rigging freshly tarred and rattled down, and the house flag flying at her peak.

“They tell me these Spanish women wear no stockings,” Arad’s friend, Captain Michael O’Cain, was muttering in his ear.

Arad replied somberly, “How is a man going to tell? You shouldn’t lean so hard on hearsay, Michael.”

Orderlies in powder-blue uniforms, cocked hats and jack boots, with heavy carbines on their shoulders and long steel swords jangling at their sides, were riding up and down madly, keeping order. The sun was sinking now, and one of these orderlies blew a blast on a trumpet. As if by a flourish of magic, the line of carriages, headed by the captain general and the archbishop of Manila, stopped; the military band of black soldiers was hushed; and by common consent, all — gentlemen, orderlies, soldiers and servants — took off their hats gracefully to repeat a silent vesper prayer. Captain Arad saw that Doha Delfina still sat erect, unmollified. She was bareheaded, her shoulders narrowed under her black mantilla, the last gleam of the sun’s upper limb reflected in her eyes. The fierce warrior’s head of Jamboo, the interpreter, was just beyond her, fixed in an attitude of attentive worship, but his divinity was nearer, evidently, than the flaming skies.

Now the prayer was over and the slow movement of dished wheels on the yellow road was resumed. Doha Delfina passed Captain Arad so close that she might have touched him with that fan showing a picture of a fallen bullfighter; instead she masked her mouth with it, but her eyes smiled. Don Narciso was half asleep at her side. If that little yellow man should die, Captain Arad thought, Delfina, unlike the Fiji Island women, would not be found imploring his relatives to strangle her, so that she might follow him into the beyond.

By a queer chance, that very night Don Narciso was all but throttled in his bed by robbers, or more likely pirates, who had succeeded in swarming over the city walls. He was rescued just in time by the big halberdier stationed outside his door; but the pirates were in sufficient force to escape without loss of any of their number. In the morning the bay was peaceful, but the scandal of pirates actually attacking a town of these dimensions while it slept was being discussed on every corner. Captain Arad waited in person on Don Narciso, sat with him beard to beard — as Narciso himself said — in the sala of his stone house.

“I am glad,” the trader began, “to see that these rascals after all have done you no great damage, Excellency.”

Don Narciso, sitting in a white nightcap, felt of his throat.

“A man who is afraid to die never truly lives,” he muttered, with a miserable attempt at boldness, but he could not keep a tear from trickling over the lacquered surface of that famous glass eye, blown and colored and inserted for him by the celebrated Doctor Pablo.

“True,” the Yankee shipmaster agreed. “But even if these pirates are run to earth, opportunities for dying will be plentiful enough for any man placed as Your Excellency is. If you let them run wild, in the end there’s nothing they won’t attempt. Here you are, for example, in a modern city, protected by a wall and ditch, drawbridges, gates, sally ports, soldiers, with a watch set every night; yet the beggars break in and all but choke the life out of you personally.”

“Maledictions and fatalities,” Don Narciso breathed.

“Fatalities. Exactly. A broadside of my thirty-two pounders in the middle of them will furnish fatalities enough.”

“But they have escaped.”

“Not without leaving a clue. My kind friend Jamboo, Yang-Po’s interpreter, picked up one of their muskets on the shore this morning. An English musket with the Tower stamped on the lock. By a private mark I know it for a musket I traded myself to a pirate — Seriff Sahibe. I know his nest. It’s a river mouth on the coast of Borneo. You’ll know it by an island there with a queer Malay name, but the English of it is Misfortune’s Isle.

“Misfortune’s Isle. But that is the island — the island — ”

“Of the upas tree, you are going to say. Exactly. What harm? The stories about that tree are nonsense. It will neither singe the hair nor numb the faculties of those who lie under it. The Dyaks extract a poison from it, I admit, to tip their arrows with, and they worship the tree, naturally; but these other stories are pure invention.”

“But I am told that the river’s mouth is stockaded,” Narciso objected.

“We can get round that. Lash whaleboats to the piles at low tide, and as the tide rises the buoyancy of the boats will pluck the piles out like so many radishes.”

“But our arms. The weapons of my soldiers. Half the time our guns miss fire; the percussion caps are abominable. The least moisture, a squall or a fall of dew, and we are helpless. We are forced to make our own powder, since the government of Spain forbids the importation of powder into Manila.”

“That reminds me of my friend Billy Sturgis,” Arad laughed. “His owner furnished him with nothing but quakers — wooden guns, Excellency, painted black — but he smuggled aboard four actual cannon, with ball and powder answerable; and with these he beat off pirates in the China Sea and saved ship and cargo. His owner made him pay freight on the cannon both ways, when he heard of it.”

“You jest.”

“I am as much in earnest as those eight thirty-two pounders aboard my ship. I tell you, I have guns and powder enough to blast Misfortune’s Isle out of the water, upas tree and all; but — I am only a trader. Ugly stories of tyranny could easily get afloat if I effected this without official cooperation. My owners wouldn’t like it. They would argue that I had gone out of my way to unlatch those guns. I should be worse off than Billy Sturgis. Now, if I can say that you, señor, commandeered my services, I am on better ground.”

“Who are these pirates?”

“A league of three forces, principally. There are Malays headed by Seriff Sahibe; there are Dyaks — head-hunters — under Gapoor; and there is that misplaced band of Chinamen — convicts — who seized the junk in which they were being transported from Hong-Kong to Singapore. Jamboo tells me they are all members of the Illustrious Brotherhood of Heaven and Earth. Our friend Yang-Po — the Captain China — is the head of that organization, it so happens. He tells me it was founded by him to set crooked things straight. Yang-Po owes his life to me. His junk is in the bay, and he agrees to pilot us into the shadow of Misfortune’s Isle. My friend O’Cain, if you consent, follows us in my ship, the Water Witch.”

“And do not forget, Don Narciso!” Doila Delfina cried — she had suddenly come on the scene, exquisitely girlish in flowered English muslin with a gardenia blossom in her hair. “We heard only yesterday that Spain will make any man count of Manila who will rid these waters of pirates.”

“But suppose Yang-Po cannot persuade these Chinamen,” Narciso faltered.

“Well, what are a few Chinamen more or less? Knock ‘em down; they’re only tea and rice. Set me ashore at that stockade with two loaded pistols,” the trader said sternly, and with cunning grandiloquence suited to the Spaniard’s needs, “have I not still an advantage? Do I not stake my one life against two others?”

“Ah, Dios,” Delfina murmured in a tone of worship, “quel hombre!”

What a man. This murmur turned the edge of all Narciso’s arguments. He was in the miserably equivocal position of an arrant coward with a widespread reputation for courage and an ambition to maintain it. His restless wife had three times already, on the coast of Chile, goaded him into lucky undertakings. As he sat now, he was Knight of the Grand Cross of the Military Order of Saint Hermenegildo, and of the Military Order of San Fernando, and decorated with seven more crosses of merit for war services — once removed — in the campaigns of both hemispheres.

“But you, señor captain — what have you to gain?” he finally demanded.

“Trade. I don’t want to conceal anything. This river is full of gold and antimony ore, and the limestone cliffs of the island, I am told, contain edible birds’ nests. My friend Houqua at Canton loves bird’s nest soup. He will give me a shipload of raw silk and broken silver in exchange.”

Don Narciso got up hastily and said he would consider the proposition further. Flanked by huge halberdiers and standing at the head of a broad damp flight of stone stairs in his earthquake proof house, he shouted down to the retreating Arad the various honors imparted, the signal obligations conferred by Arad’s presence, by the mere shadow of his shadow, on this house and on the family of which he, Don Narciso, was the least considerable member. Dona Delfina stood darkly, ravishingly limned against a lime-washed wall. Captain Arad was stirred; he felt a wash of subtle emotion in his blood. It was as if he had glimpsed under a flying moon the wings and heels of a superb China trader, going with the strength of the monsoon, and suddenly sliding up onto a coral shoal and sticking fast, so that no press of canvas could snatch her off into the deeper water.

“Adiosito,” her lips had fashioned noiselessly — a little farewell. A farewell with the ghost of a return in it. At Felipe Bustamente’s noisy boarding house, when O’Cain roared “Does the lady wear stockings or not?” Arad said somberly, “No matter for that. She has a soul, Mike.”

When he found, after the expedition had started, that Dofia Delfina had stowed herself away aboard Yang-Po’s venerable junk, Captain Arad wished he had not thought so much about the lady’s soul. This piece of folly on her part was a threat to trade. If Don Narciso knew she was aboard, he would be quite capable of turning the ship’s head for Manila. As it was, he had almost beat a retreat when they had lost sight of the Water Witch in a squall.

It was on the night following that Dofia Delfina, barefooted, in the half-breed’s costume of blue-and-white-striped pantaloons and a straw-colored pills shirt, put herself in Captain Arad’s way. This was in the waist of the ship, near the big pole mast, and in the shadow of one of those enormous bell-mouthed cannon. She hungrily filched a cheroot from the pocket of his coat. She had, she whispered, got herself brought aboard as a sack of feathers. Was he surprised? But she would contrive to make herself useful, she assured him. She would stay concealed until Don Narciso’s knees showed signs of buckling under him, and then Captain Arad would see how she could stiffen him. One way or another, she had been present at all his campaigns, and always with good effect.

“Is his nerve still good, after last night’s squall?” she inquired.

“Not too good. He fell and bruised his hip.”

“If it had not been for those feathers in which I came,” Delfina said, “I should be nothing but bruises now. It was worse than the earthquake — this squall of yours. Then, when I heard the cannon fired, I thought the pirates had attacked us.”

“We fired that shot to shatter a waterspout.”

“And you succeeded?”

“Yes. At least we got the contents of the spout, but in the form of heavy rain, instead of solid water. But the plague of it is, the rain got through the decks into-the powder tubs. Our powder is useless — all except that in the firecrackers. But there’s no going back. We haven’t water enough left. And everybody got so excited over the waterspout that nobody thought of catching water when it fell — or nobody but me, and I prefer river water.”

“You would.”

“Keep in this bag of feathers one more night, and I will make you a grandee of Spain,” Arad muttered. “Condesa.”

“Ah, condesa. That is good.”

“But now I must get up where I can watch Yang-Po’s piloting.”

“Buenas noches,” Delfina whispered, and blew smoke deliberately into his ear. “How well this title would become you, señor — el conde. The great count with his black hair, and this mouth which it is certain you have inherited from your mother. It is so very sweet. Ah, adiosito.”

The foot of the bamboo ladder he ascended had pasted on it a red label in the Chinese, reading, “May the going up be peaceful,” but with Delfina’s smoke — her fire — hot in his ear, he couldn’t at once recompose himself.

Yang-Po, the Captain China, had been smoking opium, and now, to keep himself awake, had knotted his pigtail to the rigging above his head. He swayed like a hanged man with each motion of the junk, but each time they swam past one of these black headlands, the helmsman sent Jamboo, the interpreter, to touch the Captain’s shoulder. Whereupon the Captain would look at his chart and order a cock sacrificed to the Queen of Heaven. The chart, unrolled at his feet, was on peach-colored rice paper, and showed the one proper courses straight track — with serpents and dragons writhing out of the deep on every hand. Arad, glancing over Yang-Po’s shoulder, went a little cold to see that on this chart Siberia was jammed up close against Africa, with disastrous effect on the two or three surrounding oceans. Still, it was likely that Yang-Po knew his ship’s footing in these waters.

But Don Narciso appeared to have his doubts.

“You are sure this man knows where he is going?”

“He cannot fail,” Arad said. “I know him of old. I met him first when he was a student at Canton, a literary graduate of the third degree. That, of course, is a guarantee that he has learning enough to fill five carts. Later he was one of the keepers of the temple of the Silver Moon off Lin Tin, and he used to come out and beg rice of us when we were bound down the China Sea.”

“Beg? Beg, you say?”

“This rascal was born begging. Whenever we smoked the rats out of the ship he was at hand to catch them when we threw them overboard. A forehanded man, Excellency. Later he was foolish enough to sell us, out of the Number One Temple at Honan, the sacred hog that was being kept to die of its own fat. We bought it for opium, and that came to the emperor’s ears. Our man wasn’t judged fit for strangulation after that. They crammed the wooden collar over his ears instead; that thing was four feet across any way you measured it. Yang-Po couldn’t lie down, he couldn’t feed himself, and the penalty is strangulation for feeding anybody in the collar, as you know. I found him in a ditch, took him aboard the Witch, got the ship’s carpenter to saw the collar off, and gave him rum and salt horse. You see whether he is obligated to me.”

“It was after that that he joined the Brotherhood of Heaven and Earth?”

“Yes. He and this fellow Jamboo joined forces, got a fast sampan, and preyed on the Chinese market boats and petty traders coming into Batavia — those fellows who do smuggling business with the Dutch monopolists. Our friends got some pretty rich hauls. Molucca spices, coffee and pepper from Sumatra, gold dust, camphor, slaves and rattan from Borneo, tin from Banca, tortoise shell and dye woods from Timor. You can imagine they weren’t long in getting to be pretty respectable citizens, Excellency. Jamboo was busy learning all those languages; and, in fact, I believe the fellow knows the very language of the birds; he will tell you what the trees are whispering in these plaguy rivers.”

“You say they are pirates themselves?” Don Narciso said, aghast.

“Not any more.” Arad laughed. “Not since they got hold of this junk. No, they are traders, like myself. This very voyage, for example, the junk is full of — sacks of feathers,” he dropped out with a grim twist of his mouth and a look over his shoulder at the crooked pole mast of ironwood with the bark only half scraped off. “You will find, Excellency,” he went on, quoting Byron, a favorite of his, “that this Captain China is as mild a man as ever cut a throat.”

Don Narciso brought out, with a quaver, that they ought not to close with these pirates before sighting the Water Witch, lost sight of in last night’s squall. “Our powder is useless, remember,” the captain general of Zamboanga said.

“That may be a providence. These gun barrels are cracked, and wound with nothing but bolt silk. The touch holes are as big as the muzzles. Two men were injured destroying that spout last night. Better, in any case, trust to stabbing knives.”

The fierce Jamboo, in his quilted fighting clothes, came direct from the helmsman to say that Misfortune’s Isle was now in sight. Yang-Po untied his pigtail, picked up from the chart his supper of salt, dried vegetables and rice in a coconut shell, and lifted the canopy of red cloth over the compass. The little whirligig of a man there, carved out of sapan wood and fixed to the huge needle, kept on pointing his finger north. The limestone cliffs of Misfortune’s Isle were close enough for them to see the broken coral belt at its foot, gleaming in wicked white patches against a black background of mangrove jungle on shore.

“Do we attack tonight?” Jamboo inquired, grounding his spear on the deck. His bronze head with its cluster of godlike curls moved closer. Arad, remembering the look of worship he had cast at Delfina on the Calzada, thought it would be just as well if Jamboo, as well as Don Narciso, remained in ignorance of her presence on board. Jamboo was a waif, he did not know his own father or so much as the place and hour of his birth; but to an imaginative man, this may have advantages. These slumberous watches, when he had had nothing to do but shake awake that stuffed figure of the hanging Yang-Po, it had been easy for Jamboo to imagine himself the son of a king, or perhaps a pirate by descent, as he was one already by taste. What if he were the son of Serif Sahibe himself, and so in his own person the inheritor of these resplendent gardens of the sun and master of fierce lives? Yet, in fact, he was only an interpreter.

“Attack? There is no hurry,” the Captain China yawned. “The coiling Peach Tree of the Royal Lady of the West was three thousand years before it had a blossom, and another three thousand before it bore fruit. Who knows whether it will be necessary to attack, venerable elder brother?”

“But if we do not attack the tiger in his den, how shall we have his cubs?” Jamboo insisted.

“I have been dancing with women in the palace of the moon. I cannot answer questions,” the Captain China said. “Sacrifice a cock,” he ordered, “to the Queen of Heaven.”

In the storm just passed, the Queen of Heaven, sitting in her apartment aft, cross legged in a ribbed and gilded shell, had toppled, and would have fallen if some of the sailors had not, with their profane hands, held her in her place.

“She is weak!” Jamboo had cried.

“She is angry, perhaps,” the Captain China had suggested. On either hypothesis, it would do no harm to shore her up.

The other omens were not too auspicious. The waterspout was nothing in itself, but the bursting gun had made the cannoneers timid about serving the other guns. Moreover, Don Narciso’s black soldiers had been wretchedly seasick the whole time, and some had filed the sights off their guns because of a tendency to catch in the clothing in rough weather. Again there were signs that the typhoon was not yet done with them — as, the sinking of pale phosphorescent moons through the water at night, a spotty haze following a red sunset, the haze alternating with clear patches in which the summits of the hills showed black, and finally an irregular swell across the oily face of the waters. If that Bully of the North meant to resume his antics, it would be well to have an anchorage, the Captain China said.

The upshot was, they put the junk fairly into the shadow of Misfortune’s Isle. When the limestone cliffs seemed ready to fall on the decks, Yang-Po made a motion of his hand, and there followed the splash of the junk’s huge, wooden, single-fluked anchor, weighted with stones. This was echoed by a single ominous note from a gong hidden at the heart of a banyan tree on the right bank of the river. Yang-Po answered with three peals on a gong of his own, and all was quiet.

Morning showed the two yellow tablelands of Misfortune’s Isle not a biscuit’s toss away. In the cleft or notch between them was set a pinnacle rock shaped like a ninepin, and reeling as if for a fall. At the foot of Ninepin Rock stood the upas tree, a mighty tan-colored trunk rising sixty feet without a branch, and crowned with a thick tuft of glossy dark green foliage. Even by morning light, the great poison tree, with its clustering legends, had something eerie, ominous, about it. It stood solitary on its blasted island. Not another tree, not so much as a shrub or spear of grass, was visible there, from the sinister circular halls high on the table-lands, where the Dyaks hung and smoke-dried heads, down to the beach of black volcanic sand at the foot of the upas tree.

Even Arad, getting into the lowered whaleboat with Jamboo and the Captain China, was glad to turn his eyes away from that tree and toward the river’s mouth, where morning was breaking in a hot golden haze back of the stockade closing the channel to anything larger than a proa. The lookout banyan tree on the right bank was full of bamboo ladders, and red monkeys hung chattering from the rungs of these. The tree was deserted, except for the Hue flash of the day-flying moth and the flit of leaf-green pigeons with blood-red eyes and feet. The whaleboat passed so close that Arad, standing in the stern sheets, could see the gleam of scarlet figs with honey drops at their tips; and in a few more strokes, they were in the shadow of Seriff Sahibe’s house.

The proa called the Singh Rajah, its brass swivels shining in the sun, was moored abreast of this house and was crowded with men. But nobody opposed Yang-Po’s going on into Seriff Sahibe’s house. This house, perched thirty feet over the water on slender legs, they entered by a ladder of notched logs leading to a hole in the floor. An alligator basking on a stone shelf half in and half out of water slid into the mud like something rolled on casters.

Seriff Sahibe himself was in an antique tunic of chain mail and a helmet decorated with bird-of-paradise feathers, but his legs were bare. He was sick, and lay on a bamboo platform raised a foot or more off the floor, since before now Dyak slaves and others had been known to circumvent the guardian alligator and thrust the tips of poisoned spears through the bamboo flooring, with its flimsy snaking of rattan, and into the bodies of unsuspecting sleepers.

Gapoor, the Dyak chief, was also here. His huge brass earrings he had turned up and toggled against his skull by a tiger tooth thrust through the upper part of the ear itself. This would prevent a sword from shearing the ear from his head, and was a warlike sign, which Jamboo and the Captain China recognized by merely squatting on the floor instead of sitting cross-legged. Both had previously eased their sarongs up over the handles of their stabbing knives.

Gapoor’s Sulu wife, in yellow clothes, and fair as an Italian, with her forehead shaved to match the narrow double arch of hair-line brows, offered betel-nut juice out of a silver mortar. All but Yang-Po drank, and nothing broke the decorum of Jamboo’s harangue except now and then the alligator’s rubbing his scales against the bark of the house posts, or once suddenly snapping to his jaws, which might have been wide open for ten or fifteen minutes through sheer laziness or inattention.

More insidious was the occasional creak in the rafters, a subtle swaying of the whole house on its attenuated legs; due, Arad found, to the weaving and looping, in the dark overhead, of Serif Sahibe’s pet anaconda, whose body was as thick through as a strong man’s upper leg. There was apparently no end to him. He did nothing worse, actually, than dislodge a couple of centipedes from the thatch; but once or twice Arad knew, by a sickening odor and an arrested expression on the handsome face of the Sulu wife, that the seeking head of this pet was within a foot of his own. If the conversation, through any blundering of Jamboo’s or through Gapoor’s misinterpreting the most innocent words, took a wrong turn, who could answer for the disposition of those giant black folds?

But so far Jamboo was doing very well. He explained to Seriff Sahibe that the white shipmaster had come to trade, and would pluck the riches of the limestone caverns of Misfortune’s Isle to gratify his Chinese friend Houqua’s palate for bird’s-nest soup.

Seriff Sahibe played with his toes and asked why the shipmaster had not come in his own ship? That was pertinent, and Jamboo replied glibly that the shipmaster’s ship was refitting at Manila, and that the Captain China was his friend and knew these waters. Seriff Sahibe fluttered his lids. Perhaps he thought it more likely that the Captain China had been retained to detect frauds. The Captain had a gift that way, as was known. If the Dutch at Amboyna hung their clove bags over water to increase their weight by absorption, Yang-Po would know it by squeezing the cloves in his fist. Again, if the Hong merchants at Canton offered, as tea, chopped elm and willow leaves dyed with Prussian blue, or if the traders at Bombay adulterated opium with pounded poppy leaves and camels’ dung, Yang-Po’s counsel was invaluable. He knew, too — this literary graduate, with his five cartloads of knowledge — how to test the purity of camphor; and he could tell gold from brass filings by simply picking up the stuff on his wet finger ends.

Whatever his thoughts, Serif Sahibe listened politely. The Captain China seemed innocence itself. He accompanied Jamboo’s remarks with lifts of the brow, shrugs, head slants and polite hissings, but the pirate knew that members of the Brotherhood of Heaven and Earth had to be watched for small signs. Fatalities might result from not knowing the difference between Yang-Po’s twirling his cue from left to right and from right to left. But only men born to set crooked things straight would know how to interpret it if a silver cup containing betel-nut juice should be lifted with three fingers instead of two, or set down untasted on the flat of a war drum. Certainly the Captain China had not drunk his liquor, which was a breach of etiquette, and he had not sat cross-legged in the presence, which was a worse breach.

When the conference broke up, everyone was as wise as when it started, but the whaleboat returned safely to the junk. That night Jamboo deserted, and despite peril from ranjows — sharpened bamboo stakes concealed in the ground, with poison at their tips — made his way, it was known later, to the Malay camp.

“Ten thousand bushels of sorrow, how could I suppose this?” the Captain China asked Don Narciso.

“Pick up the anchor and make sail,” the captain general urged. “This man will tell them the truth about us.”

“There is one truth torture cannot wring from him, because he does not know it,” the Captain China said sleepily. “That is, that we are, aground here, on stiff green mud. There is no moving.”

“No moving?” Don Narciso gasped.

“No moving. It is best to retire and take opium.”

Don Narciso fell back a step, fetched up on the point of his sword, and muttered, “Perdido” — lost. Standing in hot sunshine, which struck also those cliff faces of Misfortune’s Isle, and the snake-green leaves of the ghastly upas, Don Narciso cast a horror-stricken look about him. Nature perhaps had joined man’s conspiracy against his life. He put a hand to his throat. This air was next to impossible to breathe. It might be nothing but a distillation of those venomous leaves, dropped into a man’s blood stream.

“Some kinds of trouble can be avoided by fleeing with a bag of dogwood tied to your arm and drinking chrysanthemum flower wine as you run, but this is not that kind of trouble,” the Captain China informed Don Narciso. “Excuse me, august one, if I spend a part of this evening dancing with the women in the palace of the moon.”

This was the same as smoking opium; and the helmsman brought him his pipe. Narciso shut himself into his cabin, and Captain Arad was able to seek out Delfina, who lay in the shadow of the giant mat sail, crumpled across its two horses.

“The Witch is not in sight?” she whispered.

“No. But there is worse news. Jamboo, the interpreter, has betrayed us.”

“Never.”

“He has gone ashore.”

“That is perhaps to spy. I must tell you my secret. It was Jamboo who brought me aboard personally on his shoulders in that bag of feathers. He is my slave; he has no thoughts except what I put into his head. ‘It was I who got him to put into your head the very idea of this expedition, senor. Confess, he was the first to approach you on the subject.”

The first. This was true. It had been Jamboo who brought him that English musket and suggested the availability of Yang-Po’s junk. Delfina’s mirthful eyes gleamed very near.

“You say that you —”

“I. Yes. I was bored to the whites of my eyes in that sleepy Manila. I prayed for anything — pirates, a change of husbands. Then Jamboo came with that musket, and I had sent him to you before I thought twice.”

“Well?”

“You see. He worships me,” Delfina explained with a confident motion of her lips.

“Worse and worse. He must think his chances of acquiring you outright, without let or hindrance, are better from the other side. It’s probable now he has bartered away what information he has for the promise of you. No doubt he will go right on worshiping you after he has taken you up into his bamboo house and set you to pounding betel nut,” Arad went on a little ferociously. “They worship white women here traditionally. The story is that they have got one penned up in this cursed tree hanging over our heads, but I don’t know.”

“You frighten me!” Delfina cried. “You think, señor”

“I frighten you too late. And I don’t know what I think. I think the earthquake should have swallowed you. I think I ought to let these Dyaks have you. They know how to treat infidelity.”

“Infidelity? Señor — señor!”

“Isn’t that the name for it, when a wife tries to get rid of her husband by taking advantage of his weakness for titles? These Dyaks, for a less offense, would bury you to the waist and stone you with medium sized stones. That’s the penalty in their code. Well, is Jamboo’s worship worth this? I suppose you return it. No doubt you two will live together happily, once Don Narciso’s brains have been eaten and his head hung in the smokehouse.”

“You are beside yourself,” Delfina cried faintly. “How can you doubt that it is you I worship? From the very instant of my vesper prayer, senor

“Chut.”

Doha Delfina was as silent as if he had closed his hand about her throat. There was a sound of guitars forward in the hands of the Indian chamber band, playing to keep Don Narciso’s spirits up. This gust of music died, and there was nothing but a spluttering of firecrackers, a creaking of the bamboo quarter galleries under the tread of yellow feet, a bubbling of oil in the cook room. They were boiling it in three cast-off whalers’ try-pots, to pour down on the heads of pirates. Captain Arad, looking down at Delfina’s dark slenderness, saw her shoulders move. She was sobbing quietly. He felt like a warrior whose best weapon has been struck out of his hand in the very hour of battle.

“Come,” he said softly. “I must get you out of this ship before the attack.”

It was dark enough on the table land over the upas tree, but Arad went fast, scarcely waiting for Delfina to get her breath. She was sopping wet in her striped silk pantaloons and piña shirt; but she had swum away from the ship’s side with her head well out of water, unwilling to get her hair wet; and now, withdrawing thorn hairpins, she let the dry hair down round her modestly.

Captain Arad had a coil of rattan rope on his arm and a canvas bag in his fist, with food, torches and water. The climb here by that series of notched logs hung against the face of the cliff had not been easy. The notches in the logs were far apart, forcing him to bring his knee practically to his chin for each step; and most of the way he had carried Delfina, lashed bodily against his back with a few turns of the rattan.

“Here’s the mouth of that cave I spoke of,” he said, barring her way with his arm. “It’s crammed full of birds’ nests, and there may be a bat or two, but nothing to frighten you. You’ll have food and water, and rope to help you down when the time comes. I’ve told you that we are as good as dead men on the junk. Jamboo, your friend, has told those beggars that our powder is worthless; and they outnumber us ten to one. But there’s still a chance to save O’Cain’s skin and yours. I don’t know what’s delaying him. He may have struck on a shoal; he may have foundered. Well, say he has; say he’s sitting in an open boat now with the salt stinging him and only a pillow case of moldy bread between his knees, he’s still making for the island.”

Delfina didn’t answer, and Arad, prodded by the mention of O’Cain, asked out of a clear sky, “Do you wear stockings in Manila?”

Delfina had seemingly not heard one syllable of this. She murmured, her lips stiff with horror, “I cannot be left here. Señor, no, no. I had rather the poison of the upas killed me. . . How near it is. It is not twenty feet down to Ninepin Rock, and from there I could easily jump into the top of the tree. . . Señor captain, I am growing numb already. I cannot feel my toes; my hands are cold. Do you not feel yourself a dreamy something here, as if — as if our souls had slid out of our bodies?”

“No. The soul is the grain, the body is the sack containing it, Yang-Po says. When the grain — the soul — is out, the sack loses its shape. But you are evidently still in possession of your soul, señora. You will be able to give O’Cain his signal.”

“His signal?”

“These torches.”

“I had forgotten. . . They say there are no fish in the waters round this island, and that birds flying over it drop dead.”

“Birds are mortal. They must drop dead somewhere.”

“Still, nothing is growing here. Not so much as a shrub.”

“I don’t deny this tree has poison. Its sap is a kind of yellow froth, and Dyaks put it in a hollow reed with ten folds of linen round it. But it’s nonsense to say it poisons the air or withers the soul.”

“Still, the manchineel —”

“I know. But a drop of dew from the manchineel must actually fall on your skin to blister it. There’s another tree — I forget its name, but it shakes like a reed if you touch it, and it will wrestle you down if you pick it up by the roots. For that matter, I’ve seen fire coming from the camphor tree in Houqua’s gardens at Canton, but it’s a queer kind of fire that won’t even singe the hair.”

Yang-Po’s junk, hung all round with scarlet lanterns, gleamed in the blue abyss under their heels, and in the shadow of the upas tree.

“At least, do not leave me for a moment,” Delfina murmured pathetically. She tiptoed dangerously near the edge of the cliff, and Arad, with a restraining arm around her, felt her hair like the brushing of black flame against the back of his hand. “You say a woman is supposed to be imprisoned in this tree?”

“A white woman, the story is. She had sinned. The bitterness of her tears mingling with the sap is what gives the poison strength. Her imprisonment is her power.”

“Her power for evil!” Delfina cried, shuddering closer.

“Well, anyway, as long as she’s nipped here, just so long these fellows go on getting a first-class poison for their blow pipes. But it’s on the cards, they all admit, that sooner or later she’ll escape. And that, if I’m any judge, will knock them cold as a gun. . . I must get back,” he muttered, without, however, stirring hand or foot.

“No, señor,” Delfina said in a very small voice.

There must certainly be some subtle poison in this tree — or was it the poison of Delfina’s iron little will? It was the sort of poison that forces a man to ply himself with arguments. Why, after all, should he return to the junk? Why stir himself to save the life of that opium-fogged literary graduate or the still less useful captain general of Zamboanga? It was better looking down from this safe aerie, with Delfina’s head ever so lightly posed against his shoulder. . . But where could she have learned that habit of the Dyak women of binding up flowers in the hair at night, so as to impart a fragrance to the strands? . . . He breathed deep.

“I will not have you killed before my eyes,” Delfina faltered, and grew heavy in his arms.

“If I am killed, my thousand pieces of gold,” Arad whispered, using the words of the Malay warrior to his principal wife on parting, “wind about me this yellow sash from your waist, strew my body with petals from your hair, let my sightless eyes feel your salt tears, and may my ears hear the whisper of your faithful soul, borne to me on the winds of the eternal.”

“You tear me in pieces. . . Señor, they are doomed. Let them die, and let us die here by ourselves, apart, in a day or two — under God’s frown. Or possibly, if God wills —”

“You are a worse poison than the upas!” Captain Arad shouted. He thrust her away from him into the cave’s narrow mouth. Before the drumming of the swallows’ wings had died, he was over the cliff’s edge and halfway down that dangerous log ladder.

The Captain China, very somber in his mulberry-colored jacket, had with difficulty brought himself back from the arms of those women in the palace of the moon. What he saw on board the junk inclined him to return forthwith to that celestial employment, which had no moral reckoning. The cannoneers were piling up lumpy cannon balls of malleable iron between the guns; the largest of which, cracked from end to end of its barrel, but tightly wrapped with many windings of a good quality of silk, had a red label on the breech which read, The Solitary Idea. But the solitary idea of this gun was to frighten the enemy by posing in the mere likeness of a gun, as Yang-Po well knew.

Brass oil cups with floating cotton wicks burning in the bottoms of buckets threw a weird light into the sweating yellow faces of the stone carriers, who were piling huge boulders and red lacquered stinkpots in the quarter galleries; and the black soldiers of Don Narciso were aiding with noisy prayers.

Don Narciso himself, the fierce gleam of his undaunted glass eye within a foot of the Captain China’s face, cried out, “Are no measures to be taken?”

The Captain China said, “Ter-Haar, thou son of a burnt mother, hand here the rice spoon.”

A cosmopolitan spirit, he believed that superstitions, like religions, had their grain of truth. Ter-Haar, a Malay seaman, brought a huge wooden spoon to which lumps of rice still clung; and the Captain China muttered an incantation which would have dropped the arms of Dyak rowers at their sides if it could have been brought to their attention. But in the very midst of it the Captain China’s head fell forward, he lapsed for whole heartbeats into that favorite world of his, more vast and inconclusive, whose parapets swarmed with women of the moon. Their eyes were like sloes and their fingers twined in his pigtail. Still the earth would not let him go.

“If our enemies prevail after all these exertions, it is just. It is because we have maltreated them in a former life,” he muttered sleepily. Arad shook him savagely.

“This ship is bedlam!” the Salem master cried. “What are those devils yelling for down there?”

“They are giving orders,” the Captain China said, as if already asleep and answering some question put to him in a dream. “They are all commanders in their own right.”

He sank to his knees. Arad, seizing his pigtail, took a hitch with it to a piece of ratline stuff overhead. Yang-Po, his heels off the deck, smiled beatifically, and remained hanging, with his head fallen forward and his arms folded on his chest, in the customary attitude of a pilot.

“Your kindness to me,” he said faintly, “is like the touch of spring on a dying tree.”

“Hist! They are coming!” Don Narciso cried to Arad. There was a moment of comparative quiet, but even so, the rolling of a Malay oar in its rattan grommet could hardly have been distinguished from the sound of a fish jumping for a moth. The dazzle of lights necessary to the Chinese in battle made it impossible to see a dozen feet away from the junk’s side.

“These fools,” Arad muttered, “will probably dump all those stones into the water at the first rattle of an oar.”

“What — what tortures do these tribes use with prisoners of war?” Don Narciso asked thickly.

“They have no invention, really,” Arad answered, staring toward the mangrove jungle. “Ordinarily they bind a man face down to a bamboo platform with a hole in it just at the fifth rib; and a sharpened palm shoot just under the hole grows into the victim’s heart. Nature is swift here. The palm shoot kills in from twelve to twenty hours. If they have a little more time they smear a man’s naked body with wild honey and hold him crushed down against an ant’s nest. That is more artistic.”

Don Narciso pulled at the ends of his mustache in quick succession with the same hand.

“The thing is, not to be caught. And let me warn you now, Excellency, against those long poles of theirs ending in flesh hooks. When they get close enough, they shove these things over the rail and drag you overboard, like spearing eels. Keep in the middle of the deck until the stinkpots have been thrown.”

The gong in the distant banyan struck once. Captain Arad ran down three or four bamboo ladders and came to the guns. The gunners stood waiting in white clothes, with crimson symbols for victory and happiness scrawled on their backs, and matches smoking in their hands. The powder tubs were uncovered, but since the powder was hopelessly bad, there was no harm in that. Through an open sea door, Arad could see the Queen of Heaven, with countless cups of cold tea untasted at her knees. Centuries ago, a virgin, she had saved her brother, who was on the point of drowning, and had been deified. This accounted for these prostrations, thumpings, decapitations of fowls, and the knocking of already flattened noses on the teakwood deck.

A voice cried in Arad’s ear, “Do you not hear, my officer, that wailing cry of a night bird? That will guide them. If it is in front of them, they retreat; but if it is behind them, they advance.”

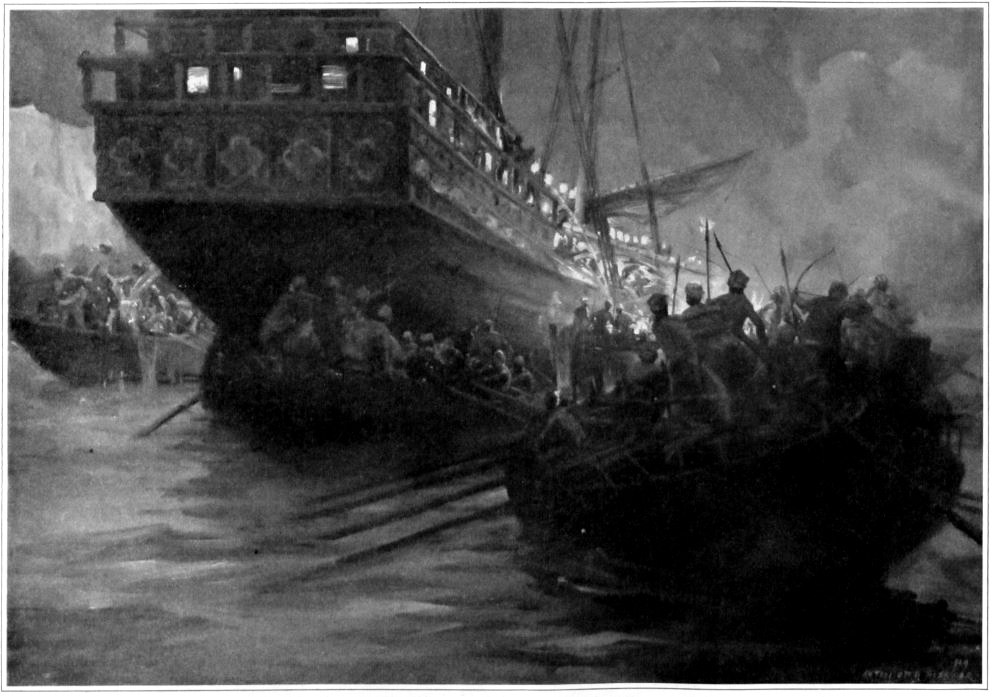

A heart-stopping yell all ‘round the junk, with a mad outburst of gong music, showed how the pirates had taken advantage of that bird’s advice. Jamboo was known to be able to interpret cleverly the language of birds, and he would naturally favor an attack. The Chinese ship comrades yelled “Hi-yi-yi!” and began to roll their boulders overboard. They also rushed up to the galleries giant ladles of boiling oil, slopping over at the edges. And they threw thousands of firecrackers. But they could see nothing — not so much as the shapes of those murderous proas — and they were in too much of a hurry to be rid of their boulders. It was unlikely that Seriff Sahibe had risked more than a handful of his proas to draw this clumsy fire of stones. Even now a splash and roll of oars showed that he was in retreat.

“We have beaten them off!” Don Narciso cried, running to the ship’s side.

“It took the whole of our artillery to do it,” Arad reminded him. “They have simply drawn our fang. They’ll be back before we have time to boil more oil.”

“Where shall I take my stand?” Don Narciso asked fearfully.

“Ask the Queen of Heaven,” Arad answered.

The proas were closing with the junk again; and out of nowhere, at the end of a shining bamboo pole sliding along the rail over the cold, stiff-necked cannon, a hideously pronged flesh hook appeared. It drifted straight for Don Narciso. The unlucky captain general was paralyzed with horror. It was plain that he was not going to be able to exert himself to dodge this hook, and Arad got a hand in his collar and yanked him to his knees. The hook passed over their heads; and staring up at it, those two looked straight into an unexpected burst of yellow fire, coming from the limestone cliffs of Misfortune’s Isle.

“It’s the upas tree!” Arad shouted.

In fact, it was the upas tree that had mysteriously broken into flame. It was a giant torch, a deadly wand, flourished over their heads, destroying the secrecy of the attack and touching the hearts of warriors cold in the very heat of battle ardor. The blood-shot eyes of those followers of Seriff Sahibe rolled in their heads; for they had seen a sight which filled them with despair and terror. There was a recoiling clash of oars, spears and muskets, an indescribable banging of gongs. When the Chinese up the river had tried to frighten away a plague of locusts by beating on gongs, and again, when they had tried to banish an eclipse of the moon by the same means, the Dyaks had sneered; but they had reason now to call on all their gongs. For not even Arad’s phlegmatic western eyes had failed to see, rising as if out of the heart of the flame itself, and drifting fast, with wide-flung arms and streaming hair, a woman shape vanishing against the limestone cliffs.

And not even Arad was certain, for that second, that this was not the upas prisoner, the very soul of poison, escaping, and in a mood to call down tardy vengeance from the black skies.

Captain Arad and Captain Michael O’Cain sat with the old Hong merchant, Houqua, in his gardens at Canton. Houqua’s house was like a string of Pompeiian villas, delicately carved and gilded, hung with horn lanterns ending in red silk tassels. Priceless silk paintings adorned the walls, and here and there was scrawled in thick brush strokes the symbol of happiness.

The three friends sat outdoors by night at a black lacquered table under an ancient camphor tree. This terrace was paved with polished granite, and granite blocks of high luster edged the fish pond, where lotus leaves floated and where a company of eight ducks were performing figures to the music of a bamboo flute. This flute was in the hands of an entertainer — one of the Disciples of the Pear Garden — in an opposite pavilion. Arad got up restlessly and strolled to the water’s edge.

Lanterns were everywhere. They hung from the ivory balustrade of the steep little bridge over the fish pond, from the eaves of the house, from the lower branches of the camphor tree and from the two stone towers on the river’s bank. The bank itself was paved, but with rough granite, the blocks dogged one to another with iron dogs, and sloping gradually under water.

“Pulo Chalacca — that was the name of it,” O’Cain muttered to Houqua. “Misfortune’s Isle. ‘Tis well named. Jamboo, I hear, was stoned to death with medium sized stones — no one of them, mind you, big enough to kill him outright; but in the end they wore him down. Those pirates ran away so fast they left Seriff Sahibe’s pet anaconda behind them, and took the women and children in the old proas. Yang-Po is nothing now but a chambermaid for the birds’-nests caves; he goes around burning sulphur in them and making inducements to the birds to build again. ‘Take little and give much’ — that’s his motto now.”

“And Doha Delfina?” Houqua inquired.

“Well, she got back her little man with the glass eye, it’s true, but still and all, there she is in Manila, and goes out at four o’clock, when the sea breeze springs up, and the little postilion ahead of her in his shiny hat on the gray horse’s back. Maybe once a week she can watch the half breed women, with their hair down, waltzing with their chins on their partners’ shoulders — but what does that avail?

“And there’s Arad, here, Houqua. I’ve had Chinese doctors to him; they’ve taken his pulse in both arms from the wrists to the shoulders. There’s some out about him, and they don’t know what. Misfortune’s Isle — that’s the long and short of it. Maybe I was well out of it. Still, I would have given a shipload of broken silver for a sight of that prisoner in the tree, breaking loose in her glory and flying free at the end of that rope tied to Ninepin Rock. Whatever the custom in Manila, Houqua, she wore no stockings there. It was necessary to the scheme to have her looking like an immortal. And haven’t I heard you say yourself we shall have no clothes in heaven, because, although bodies have souls, it’s not likely that clothes have souls to match? Or if they do, who’s to guarantee that the clothes will die with the body, and not sooner or later?”

“There are no soulful garments,” Houqua agreed, tracing a symbol of happiness in the air with his pipe stem.

“Right. So there was I, a week late in the Witch, what with her grounding and ourselves dropping her guns over the side and buoying them, and rolling all the provisions and water casks aft to work her off, and then fishing up the guns again. All I got was hearsay. Narciso Crispo’s expedition, when I got there, would have been just a collection of heads hanging in the head halls with tufts of grass in the ears and orange cowries for eyes, if Dona Delfina hadn’t put that upas to the torch. Well, it’s certain the king will send them out a patent of nobility. They’re grandees of Spain this minute; Narciso is as good as Count of Zamboanga. And why not? Oughtn’t a man to be ennobled for seeing his wife float head-first out of a burning tree on a desert isle, and he with not the first suspicion of her being there? It was enough to blind him in his glass eye, and I told him so.”

It was strange, Houqua said. Yes, certainly it was Number One curio pigeon. Strange business. He had heard tell of the upas poison.

“You have an art with trees yourself,” O’Cain said, pointing at a maidenhair with fan-shaped leaves. This tree had been tortured into the likeness of a pagoda by confining its roots in stone crocks, and by other means. Here and there on the terrace were other trees, trimmed in the images of fish, camels and elephants. “You can all but make trees weep with the torture, as you do your women; but you do not know how to confine a woman in a tree. It’s a wonderful poison results, they say, when it’s quickened with lime juice. It works with a sharp burning in the head, and death. Its criminals condemned to die, they tell me, that are sent to tap the poison; and they give them leather hoods to put over their heads, and tell them to go toward the tree with the wind at their backs; and even so, only one in ten returns.

“Well, is Captain Arad poisoned then? He’s still about on his feet. Here he is with every reason to feel satisfied — a saving voyage, with the brotherhood digging antimony ore for him at Pulo Chalacca, and he with birds’ nests worth their weight in silver. . . Hist, here he is.”

“Birds’ nests,” Arad repeated, stepping out of the shadow of the camphor tree, which had a play of silver sparks out of its twigs and leaves. “We had better stick to birds’ nests, Mike. The raw nest, after the bird has flown, but before the egg has been laid. And I can sell you nests, Houqua, as big as a quarter orange, some of them, at forty Spanish dollars the pound.”

Houqua blinked his eyes. Across the fish pond one of the Disciples of the Pear Garden cracked his whip, and the performing ducks turned as one duck and swam toward him like mad.

“The last duck gets a taste of the whip!” O’Cain chortled.

“Why? There has to be a last duck,” Arad muttered darkly.

“Which proves the necessity of punishment on this earth!” O’Cain roared.

Bird’s-nest soup was put before them in three blue bowls. Arad dipped a spoon into this fabled soup. It would, Houqua assured him, put fat around the ribs, make old men young and young men able, and perform other marvels, such as making pirates homeless and filling the coffers of Salem merchant princes on the other side of the world. Yet it seemed to Arad that, considering how hard it was to get, the soup was rather tasteless. His thoughts were far away. He asked himself how these two could agree so glibly that garments — say, the flowered muslin or the striped pantaloons of the valiant Delfina — had no soul. As well say there had been no soul in that out breathed “Adiosito” from the cave’s mouth — farewell for a little, with that wraith of a promise of return in it. And as if he had been himself the last duck, the trader felt across his own shoulders the crack of the whip, and was aware that the upas poison, in some form, was in his veins, only not quickened; and that it had a power to tarnish the most gilded triumph.

Featured image: Anton Otto Fischer

In a Word: The Difference between a Swashbuckler and a Buccaneer

Managing editor and logophile Andy Hollandbeck reveals the sometimes surprising roots of common English words and phrases. Remember: Etymology tells us where a word comes from, but not what it means today.

We’re less than a week away from September 19 and one of the best holidays of the year: International Talk Like a Pirate Day! But before you start revving up your “ARRR”s or shivering your timbers, learn about the history of two words often associated with the high-seas adventures of pirates: swashbuckler and buccaneer.

Swashbuckler is a word that came together during the 16th century, and it’s a fairly simple combination of two pre-existing words: A buckler was a small shield one could hold by a handle. Swash was a verb meaning “to strike loudly or violently.” It later came to describe the sound of water splashing against a solid surface.

An overconfident duelist of the time might hit (swash) his shield (buckler) with his sword to goad his challenger on — the 17th-century version of “Come at me, bro.” So, naturally, one who showed such swagger and bravado came to be called … a buckler-swasher!

Well, no. Although we form words like that in English all the time (think dishwasher, copyeditor, and shoemaker), for some reason — possibly the influence of the French language — a person who swashed his bucklers was called a swashbuckler. These days, the word is more indicative of a person’s audacity and bluster than their skill with a sword and shield.

Though they contain similar sounds, buckler doesn’t figure into that other word for pirates, buccaneer. In the Spanish West Indies during the 17th century, French hunters and settlers learned how to smoke and cure meat from the natives using a wooden frame they called a boucan; they became boucaniers. When they were driven from their trade by Spanish authorities, some of them became pirates, and they took the name with them.