How Emma Lazarus Redefined Liberty

In 2017, President Trump’s senior policy advisor Stephen Miller disagreed with CNN reporter Jim Acosta about the meaning of the Statue of Liberty. After Acosta repeated the well-known verse inscribed at the base of the statue (“Give me your tired,/ your poor,/ Your huddled masses yearning to/ breathe free… ) along with a question about Trump’s support of reducing immigration, Miller said, “the Statue of Liberty is a symbol of American liberty enlightening the world. The poem that you’re referring to was added later. It’s not part of the original Statue of Liberty.”

While Miller’s interpretation of our colossal gift from France is rooted in President Grover Cleveland’s original dedication (“stream of light shall pierce the darkness of ignorance and man’s oppression until Liberty enlightens the world”), he omitted that Emma Lazarus’s poem “The New Colossus” wasn’t merely “added later.” It was one of the reasons Lady Liberty even had a pedestal to stand on.

Today is the 170th anniversary of Emma Lazarus’s birth, and, though many remember her only for a few lines from her most famous poem, the literary stalwart was also a tireless advocate for refugees in the 19th century.

Theater producer and literary agent Elisabeth Marbury wrote about having met Lazarus in the Post in 1923, saying “To be with Emma Lazarus produced a stained-glass effect upon one’s soul … Her ideals were sublime and her loyalty to her people was very beautiful to contemplate.”

Marbury wrote of the “poetess” and “Jewess” with the same racial reduction that Lazarus railed against in her lifetime. Though Lazarus was born to a well-to-do family, her “otherness” for having been Jewish was always starkly clear to the writer. In an 1883 letter to her editor, Lazarus bemoaned a widespread bias against Jews in the New York elite: “I am perfectly conscious that this contempt and hatred underlies the general tone of the community towards us, and yet when I even remotely hint at the fact that we are not a favorite people I am accused of stirring up strife and setting barriers between the two sects.”

In addition to becoming the foremost Jewish poet in the U.S., Lazarus used her broad appeal to call attention to the growing antisemitism she saw around her. In Russia, in the early 1880s, anti-Jewish riots — called pogroms — led to the rape and murder of Jews in southwestern parts of the empire. Refugees from these settlements came to the U.S. and faced harsh living conditions on Wards Island in New York, and Lazarus visited them while volunteering for the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society.

She also featured themes of immigration — with a particular focus on redemption — heavily in her poetry. In “In Exile,” she wrote about a Russian Jew living in Texas: “Freedom to dig the common earth, to drink/ The universal air—for this they sought/ Refuge o’er wave and continent, to link/ Egypt with Texas in their mystic chain.”

Lazarus wrote in Century magazine in 1882, refuting a writer who had previously sought to justify the Russian pogroms: “The dualism of the Jews is the dualism of humanity; they are made up of the good and the bad. May not Christendom be divided into those Christians who denounce such outrages as we are considering [pogroms], and those who commit or apologize for them?” Common-sensical as it may have been, Lazarus’s argument that ethnic groups cannot be stereotyped or assigned broad, moralistic characteristics is one that persists in advocacy of immigrants and refugees today.

When the United States received the Statue of Liberty from France, fundraising auctions were held to construct the pedestal upon which she would stand. Lazarus donated her poem “The New Colossus,” a sonnet that compared the torch-bearing Lady Liberty to the Colossus of Rhodes, calling her a “Mother of Exiles” that welcomed downtrodden foreigners with open arms. Her poem was praised for balancing themes of modern American life with classical Greece and treating immigrant refuge with humanity. Poet James Russell Lowell wrote that it “gives its subject a raison d’etre.”

Lazarus died the year after the statue was dedicated. Sixteen years later, art patron Georgina Schuyler uncovered “The New Colossus” and began a campaign to have its lines cast in bronze and added to the pedestal as a memorial to Lazarus and her work. While “Give me your tired,/ your poor … ” might be more recognizable to Americans nowadays than Lazarus herself, the inverse was true at the time. The words of “The New Colossus” gave the statue — and perhaps the country — a broader interpretation of liberty, one that included “huddled masses yearning to breathe free.”

“The New Colossus” by Emma Lazarus

Not like the brazen giant of Greek fame,

With conquering limbs astride from

land to land;

Here at our sea-washed sunset-gates

shall stand

A mighty woman with a torch,

whose flame

Is the imprisoned lightning,

and her name

Mother of Exiles. From her

beacon-hand

Glows world-wide welcome, her mild

eyes command

The air-bridged harbor that

twin-cities frame.

“Keep, ancient lands, your storied

pomp!” cries she,

With silent lips. “Give me your tired,

your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to

breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your

teeming shore;

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost

to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

Featured Image: W. Kurtz, 1889 (Internet Archive)

Loving and Hating Walt Whitman

In its earlier years, it seems this publication couldn’t make up its mind about Walt Whitman and his divisive poetry. The poet — who would be 200 years old today — turned heads around the world with his humanist classic Leaves of Grass. The Saturday Evening Post published a criticism of the author deemed “honest, downright writing” in 1860: “He has strength, he has beauty, but he has no soul. Intellect, I grant, wide in its scope, and powerful in its grasp. Yet with all this, I doubt if, when the Judgment-Day comes, Walt Whitman’s name will be called. He certainly has not soul enough to be saved. I hardly think he has enough to be damned.”

The harsh words came from Calvin Beach, a reviewer whose 200th birthday is likely to pass by unnoticed.

In 1865, however, the daguerreotypist and Post editor William Douglas O’Connor penned a pamphlet to show the world how much soul his friend Walt Whitman actually had. O’Connor’s The Good Gray Poet heaped praise — at times unnecessarily — upon Whitman, calling him “a man of striking masculine beauty — a poet — powerful and venerable in appearance; large, calm, superbly formed; oftenest clad in the careless, rough, and always picturesque costume of the common people.” O’Connor’s vindication of Whitman came after the latter was dismissed from a job in the Department of the Interior. It was the last straw of many years of Whitman-bashing, with many academic circles and critics having described his Leaves as indecent, obscene trash, and Whitman himself as a filthy free lover and possibly a homosexual.

The Post kept up its opprobrium in 1873, musing about Whitman’s tendency to leave out the resolution of a thought in his poetry: “His stops make him popular. The more he stops the more popular he becomes. If he should stop altogether the public would give him a monument, and perhaps a horse.” Aptly, The Country Gentleman came around in 1897 with “A Defense of Walt Whitman.” While the agriculture publication wasn’t prepared to go to bat for the whole scope of Whitman’s worldview, the article admits that the poet shines from time to time with powerful language: “The healthy, vigorous and intense personality of the man seems to have entered his work and inspired it with a moral [we might better have said a tonic] force; he feels called on to instruct, and his lesson is sympathy.”

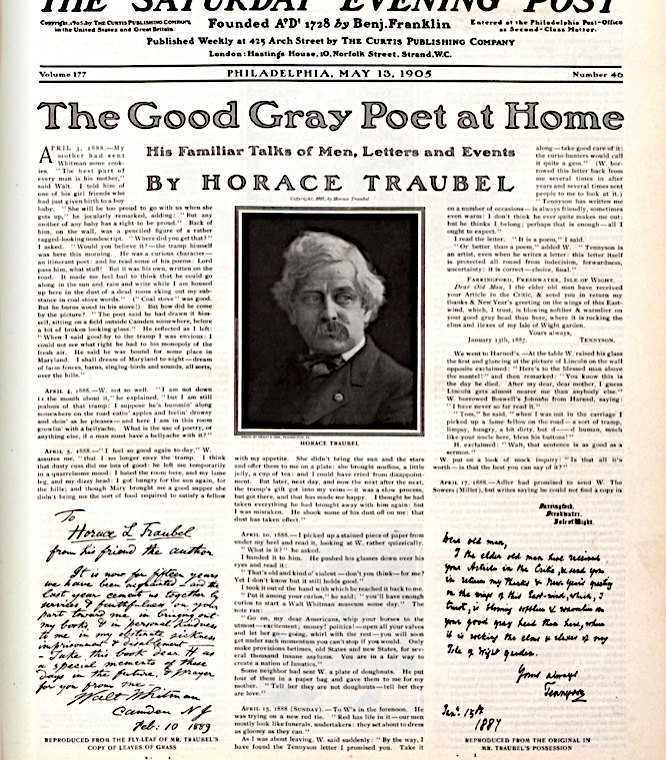

That a magazine published for rural America would support Whitman is, perhaps, unsurprising, but the Post finally paid its respects in 1905. Horace Traubel, a socialist poet and essayist, spent time with Whitman in the years before his death, compiling letters, conversations, and anecdotes in his book With Walt Whitman in Camden. His visits with Whitman in April 1888 were featured in the Post as “The Good Gray Poet at Home” in two parts.

In his final years, Whitman displayed humility, clarity of purpose, and stark honesty about his place amongst his peers. Traubel captures the aging poet’s simultaneously courageous and humble self-expression in his report, as Whitman discusses topics ranging from American morality to deserts.

The good gray poet on one of his greatest supporters, Ralph Waldo Emerson:

We were not much for repartee, or sallies, or what people ordinarily call humor, but we got along together beautifully — the atmosphere was always sweet, I don’t mind saying it, both on Emerson’s side and mine: we had no friction—there was no kind of fight in us for each other — we were like two Quakers together. Dear Emerson! I doubt if the literary classes which have taken to coddling him have ally right to their god. He belonged to us — yes, to us — rather than to them.

On Henry David Thoreau:

Thoreau’s great fault was disdain — disdain of men (for Tom, Dick and Harry): inability to appreciate the average life — even the exceptional life. It seemed to me a want of imagination. He couldn’t put his life into any other life — realize why one man was so and another man was not so: was impatient with other people on the street, and so forth. We had a hot discussion about it — it was a bitter difference: it was rather a surprise to me to meet in Thoreau such a very aggravated case of superciliousness. It was egotistic — not taking that word in its worst sense.

On America:

Someone cried out there at Gloucester: ’You’re d[amne]d tolerant, Walt!’ Am I? Call it toleration, if you choose. I only call it common-sense — philosophy. I am extreme? Perhaps. But then it is with America as it is with Nature: I believe our institutions can digest, absorb all elements, good or bad, godlike or devilish, that come along: it seems impossible for Nature to fail to make good in the processes peculiar to her: in the same way, it is impossible for America to fail to turn the worst luck into best — curses into blessings.

“I no doubt deserved my enemies, but I don’t believe I deserved my friends,” Whitman remarks, acknowledging the slings and arrows he faced over the years with a calm resolve. For a writer who spent decades perfecting his deeply philosophical and soul-searching volume of poetry, Whitman speaks of himself and his work with almost as much derision as his critics. He doesn’t take himself too seriously, and perhaps that is the key to his steadfastness in the face of truly abhorrent press (a review of Leaves in the Saturday Press suggested that he commit suicide).

“A man makes a pair of shoes—the best—he expects nothing of it,” Whitman says, “he knows they will wear out: that’s the end of the good shoe, the good man. Any kind of a scribbler writes any kind of a poem and expects it to last forever. Yet the poems wear out, too—often faster than the shoes. I don’t know but in the long run almost as many shoes as poems last out the experience.” More than 150 years after publication, “Song of Myself” is still assigned reading in schools, and the good gray poet will outlast his fiercest detractors.

Featured Image: “Whitman at about fifty” by Methuen & Co., 1905.

What Should I Write in My Valentine’s Day Card?

Roses are red, but violets aren’t blue, and if you use this erroneous cliché in a card to your sweetheart they might just dump you.

Is your holiday missive missing something? You needn’t be a brilliant bard to impress your Valentine with some heartfelt verse. Steal it from us instead! Here are some clever and romantic quotations taken straight from obscurity to grace your letter to your beloved.

“Said a Lover” by Katharine Scott (July 12, 1930)

I envy him Love first did give

The idea for the adjective,

Who first did find for passioned state

The barren noun inadequate,

And, leaning to his mistress’ ear,

Made the small words of “sweet” and “dear.”

If I had lived when Love was young,

Before a thousand years of song

Made “lovely” worn and tarnished stand,

And “beautiful” so secondhand;

When “fair” was fresh, and “charming” new,

Perhaps I should have words for you!

From “Song of a Contented Heart” by Dorothy Parker (February 24, 1923)

All sullen blares the wintry blast;

Beneath gray ice the waters sleep.

Thick are the dizzying flakes and fast;

The edged air cuts cruel deep.

The stricken trees gaunt limbs extend

Like whining beggars, shrill with woe;

The cynic heavens do but send,

In bitter answer, darts of snow.

Stark lies the earth, in misery,

Beneath grim winter’s dreaded spell—

But I have you, and you have me,

So what the hell, love, what the hell!

“Any Lover to His Love” by Mary Dixon Thayer (June 13, 1925)

Where you have been the lilies blow

More thickly, and the grass is sweet

Where you have touched it with your feet.

Where you have been, and where you go

The world is fair — so fair!

Your laughter trembles in the air.

Where you have been I wander, and

The lilies and the grass

Utter your beauty as I pass.

Even the blind clouds understand

What loveliness by all is seen

Who walk where you are, or have been.

“Juliet on the Balcony” by Howard Glyndon (January 12, 1878)

O lips that are so lonely

For want of his caress;

O heart that art too faithful

To ever love hint less;

O eyes that find no sweetness

For hunger of his face;

O hands that long to feel him

Always, in every place.

My spirit leans and listens,

But only hears his name,

And thought to thought leaps onward

As flame leaps unto flame;

And all kin to each other

As any brood of flowers,

Or these sweet winds of night, love.

That fan the fainting hours!

My spirit leans and listens,

My heart stands up and cries,

And only one sweet vision

Comes ever to my eyes.

So near and yet so far love,

So dear yet out of reach,

So like some distant star, love,

Unnamed in human speech!

My spirit leans and listens,

My heart goes out to him,

Through all the long night watches,

Until the dawning dim;

My spirit leans and listens,

What if, across the night

His strong heart send a message

To flood me with delight?

“A Question of Terminology” by Robert Zacks (February 16, 1946)

How absurd a heart can be!

When it’s bound, it feels most free.

When it’s free, it wanders round

Seeking, so it can be bound.

All this simply means to me

Words do not say as they sound;

Freedom’s not till love is found.

From “Love Song” by Charles Gavan Duffy (June 21, 1856)

The face of my Love has the changeful light

That gladdens the sparkling sky of spring;

The voice of my Love is a strange delight,

As when birds in the May-time sing.

Oh, hope of my heart! Oh, light of my life!

Oh, come to me, darling, with peace and rest!

Oh, come like the summer my own sweet wife,

To your home in my longing breast!

“The Sum Total” by Patience Eden (November 15, 1930)

In casting up some old accounts

Of psychological amounts,

I find, my dear, you have a way

Of being far more good than gay:

And when I think you’re most alive,

You’re merely bland instead of blithe,

You have a cool and classic mind,

Less brave than bright, more keen than kind;

The values of your character

Merge in a grand, majestic blur

Of awesome traits — and yet, my dear,

It’s what you’re NOT which seems most clear.

“Contentment” by Philip I. Blakesly (March 16, 1940)

When an ocean is least,

Or a world or a star,

Who cares what is most?

When the cup is full,

When the heart overflows,

There is only that —

There can be no more.

And a cup will suffice for a grander measure;

When the mind’s at rest, what more is a treasure?