Considering History: Civil Rights, Racism, and the Question of American Progress

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

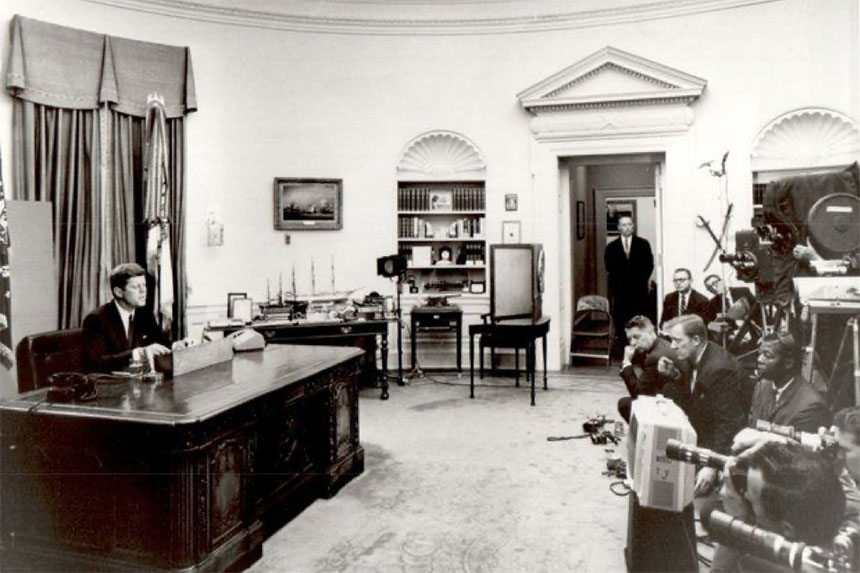

On June 11, 1963, President John F. Kennedy gave a televised presidential address on the question of race and civil rights. The speech addressed specific, ongoing events: earlier that day Alabama Governor George Wallace had literally blocked two African American students, Vivian Malone and James A. Hood, from enrolling at the University of Alabama; in response Kennedy federalized the Alabama National Guard, after the arrival of which Wallace backed down and Malone and Hood successfully integrated the university. But Kennedy used his June 11 address and its national platform to go much further than that targeted response, proposing sweeping civil rights legislation that his administration would subsequently send to Congress.

Like Martin Luther King Jr.’s famous March on Washington speech, delivered two-and-a-half months later, Kennedy’s speech frames the events of that time through the fraught question of American progress. As Kennedy notes, “One hundred years of delay have passed since President Lincoln freed the slaves, yet their heirs, their grandsons, are not fully free.” In his speech’s opening paragraphs, King extends and deepens that point: “But one hundred years later, the Negro still is not free; one hundred years later, the life of the Negro is still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination; one hundred years later, the Negro lives on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity; one hundred years later, the Negro is still languished in the corners of American society and finds himself in exile in his own land.”

A century after the Emancipation Proclamation, America had made painfully little progress on issues of racialdiscrimination, oppression, and violence. But what about now, 57 years after Kennedy’s speech, more than half a century beyond the March on Washington? While some progress has unquestionably been made, when it comes to key issues such as white supremacist violence, voting rights, and structural inequity and inequality, America remains far too close to where it was in the summer of 1963.

The areas on which the most overt progress has been made tend to be those that were directly covered by the Civil Rights Act, the July 1964 law that resulted from Kennedy’s proposal. Institutions like schools and businesses can no longer discriminate against Americans based on their race, nor any other element of their identities (although the legal battle over discrimination based on sexual orientation continues to rage). That progress is about not only access but also equality: institutions can also no longer create separate, segregated spaces for individuals of different races, and must instead offer the same opportunities or face legal and financial penalties; in one of the most famous such cases, In 1994 Denny’s restaurants were proven to be discriminating against African-American patrons and had to pay tens of millions of dollars in settlements.

But as Kennedy’s speech acknowledges, civil rights is about more than just equality of access or opportunity, and instead represents what he calls “a moral issue … as old as the scriptures and as clear as the American Constitution”: “whether we are going to treat our fellow Americans as we want to be treated,” whether every American can “enjoy the full and free life which all of us want.” And on a number of levels, African Americans continue to be denied the full protection of the law that would guarantee such freedom from discrimination and oppression.

Protection from racist violence remains frustratingly rare for 21st century African Americans. Some of the foundational incidents of the Civil Rights Movement featured an absence of such protection, from the lynching of Emmett Till and the sham trial that followed it to the ubiquitous sexual violence that precipitated the Montgomery bus boycott. Yet despite civil rights laws and more recent follow-ups like the 2019 anti-lynching legislation, those who commit acts of violence against African Americans still all too often escape justice. Some of those are civilians committing extra-judicial lynchings, like George Zimmerman’s 2012 killing of Trayvon Martin or the two men who killed Ahmaud Arbery in February (and the third who filmed it). But many are officers of the law, such as the police officers involved in the 698 shootings of African Americans between 2017 and March 2020 (22 percent of the 3,215 total shootings over that time; in another 629 shootings the victim’s race was unreported, so the percentage is likely higher still). Many of those citizens and officers were never charged with a crime; of those few who have been indicted, the vast majority were (like George Zimmerman) acquitted on all counts.

One of the principal means through which such legal injustices can be challenged is by voting in new officials, and the Civil Rights Act’s 1965 counterpart, the Voting Rights Act, extended federal voting protections to African Americans. But in 2013’s Shelby County v. Holder decision, the Supreme Court ruled that key Voting Rights Act protections were unconstitutional, adding that the country “has changed” and that such protections are thus no longer as necessary as they were in 1965. In the half-decade since the decision, that opinion has been proven entirely incorrect, as countless measures have been enacted that work purposefully and effectively to limit and deny the vote for African Americans and other communities of color. The proponents of such measures, which often closely mirror pre-Voting Rights Act practices such as poll taxes and “literary clauses,” have consistently admitted that suppressing the vote among those particular American communities is their goal.

While of course African Americans want the same legal and democratic rights as all Americans, their ultimate goals are even more fundamental and deep-seated: as James Baldwin put it in a 1968 speech, “I simply want to be able to raise my children in peace, and arrive at my own maturity in my own way in peace.” But systemic, structural inequities and inequalities make those goals far less achievable for African Americans than their white fellow citizens. Take two elements of my seemingly progressive home state of Massachusetts, for example. Massachusetts’ public schools are significantly more racially segregated in the 2010s than they were a few decades earlier, with the schools with the highest percentage of students of color receiving over $1000 less in annual funding per pupil. And not coincidentally, a groundbreaking 2017 investigative series by the Boston Globe’s Spotlight team found the median net worth for an African-American family in Boston to be $8 (that’s not a typo, it’s 8 dollars), compared to a median net worth of $247,500 for white families.

Life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. These are the inalienable rights that the Declaration of Independence identifies as core values of the United States of America. In June 1963, the proposed Civil Rights Act (like the Civil Rights Movement) sought to better protect those rights and thus make them more genuinely attainable for African Americans. As of June 2020, it remains an open and crucial question whether the nation has progressed closer to that promise, and what we must do to ensure real progress from here.

Featured image: Lyndon Johnson signs the Voting Rights Act (Wikimedia Commons / LBJ Library / Public Domain)