Saving Our Dying Waters — 50 Years Ago and Today

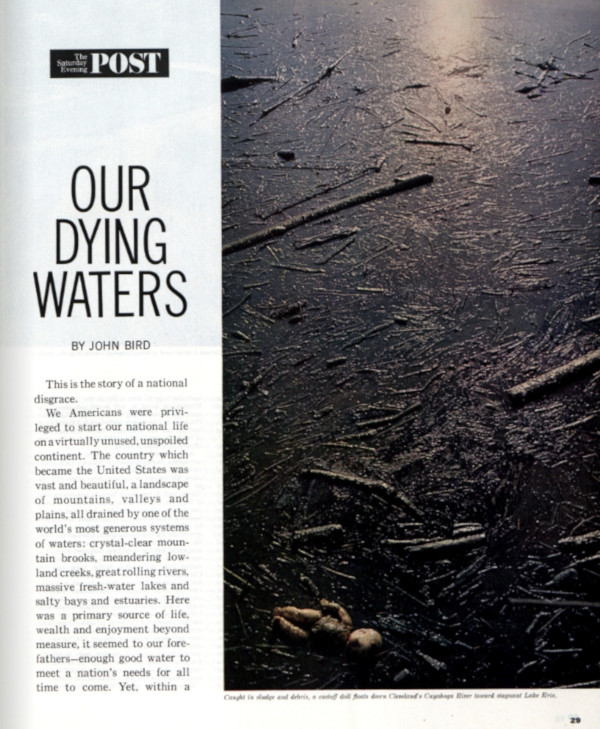

On a bright Sunday morning in June 1969, the Cuyahoga River caught fire. An oil slick atop the river caused by years of industrial waste burned with flames reaching over five stories. Three years earlier, on April 23, 1966, this magazine published an article by John Bird titled Our Dying Waters. Bird outlined the issue of America’s contaminated rivers and what needed to be done to fix them, claiming “the 21st century will be well underway before we are ready to cope with 20th-century pollution. We may choke on our own filth by then.” More than fifty years later, have we made any progress?

The outrage that followed the burning of the Cuyahoga spurred public support for political action, leading to the Clean Water Act (1972) and the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency (1970). Dying Waters emphasized the lack of regulation and outdated processing plants that heavily increased the amount of pollutants in water. Since the 1966 article, some progress has been made. The various acts that were passed increased testing of rivers and public water supplies and required closer monitoring of industrial waste. Regulated pesticides, less industrial water pollution, and more marine sanctuaries put an end to flammable rivers.

Unfortunately, contamination of rivers and reservoirs is not fully a thing of the past. An EPA report published in 2008 found that 46 percent of this nation’s rivers are in poor biological condition, leading to a loss of fishing and recreational facilities. This study reported that 24 percent of rivers have heightened levels of bacteria that “are indicators … of the possible presence of disease‐causing bacteria, viruses and protozoa.” Along with elevated phosphorous levels, mercury in fish, and loss of coastline wildlife, this report claims that “Our rivers and streams are under stress.”

The EPA introduced several methods of improving the biological condition of our rivers. The authors planned on investigating the source of the stressors, “including runoff from urban areas, agricultural practices and wastewater,” however no follow-up report has been published.

This sort of study did not exist in the time of Dying Waters, so it is unclear how the rivers of today compare to Bird’s. The major difference between now and 50 years ago is attention and regulation. Where there were no federal laws against pollution before the EPA’s creation in 1970, we have government agencies designed to test industrial waste. Where environmental disasters went unnoticed, we have contaminated drinking water making national headlines for weeks on end.

In his article Bird states that “We have taken it for granted that the water flowing from our faucets is free of disease, but we couldn’t be more wrong.” Today, roughly 25 percent of Americans drink from water supplies that violate the Safe Drinking Water Act (1974). Bird mentions the problems caused by salmonella infected waters in 1960. While there were no water-born salmonella outbreaks in 2015, 77 million people drank from water contaminated with coliform, nitrates, lead, copper, radionuclides, arsenic, and other contaminants. The 1960 residents that drank salmonella-contaminated water contracted high fever and nausea. Water quality in 2015 may have contributed to any number of ailments for the drinker from nausea and fever to cardiovascular disease and cancer.

Local and national attention surrounding Flint, Michigan, provides an excellent example of the nation’s ongoing water crisis. While the issue of lead contaminated water is relevant now (18 million people were drinking from lead-contaminated sources in 2015), lead was not even mentioned in Bird’s article. The true dangers of lead poisoning were not understood until the early 1970s.

The focus today has expanded to include water conservation as well as pollution. In 1966, the nation used 314 billion gallons of water per day. Now, although our population has increased by 68 percent, our water use has grown by only 2.5 percent to 322 billion gallons. While this is far better than the 1 trillion gallons Bird predicted the nation would need (the closest the country had come to that amount is using 435 billion gallons per day in 1980), it is still not a sustainable amount of water. While population continues to grow, the world’s water supply remains fixed. Statistics published by the United Nations predict that two thirds of the world will live in “water-stressed” countries by 2025 if current patterns of water-use prevail.

The facts are there: continuing to treat our water the way we have in the past puts millions of people at risk in addition to endangering aquatic environments. The article provides some hope for the future, emphasizing big picture ways of saving our dying water. Today there are many ways that everyday people can make a difference in our water crisis, we need only try. As Bird wrote half a century ago, “The only unknown is how long it will be before it’s too late.”

Featured image: Shutterstock