Gibbering Idiots: The War on the Populists

Just what is a populist, anyway?

Does the word have any meaning when it’s being applied to Elizabeth Warren, Beto O’Rourke, Bernie Sanders, Kamala Harris — AND Donald Trump?

Today, pundits use “populist” to describe a candidate who claims to represent the will of the common citizen instead of private interests.

Populists promise to drive the elites out of government, though not always with plans of how to replace them.

But in the late 19th century, populism had a distinct meaning. It was the philosophy of the Populist Party, which was formed to address the problems of rural Americans.

Crop prices were falling in the 1890s. A harsh tariff was driving up the cost of goods and cutting off American farmers from foreign markets. Railroads kept inching up the freight charges farmers paid to ship their produce to market. The people in America’s farmlands felt exploited by big business and Washington politicians and estranged from the industrialized America of the Gilded Age, with its handful of ultra-wealthy business men and politicians.

To correct the problems, the Populist Party held its first national convention in Omaha, Nebraska, in January 1892. In its platform, it called America “a nation brought to the verge of moral, political and material ruin. Corruption dominates the ballot-box, the legislatures, the Congress, and touches even… the bench. The fruits of the toil of millions are boldly stolen to build up colossal fortunes for a few.” The country, they claimed, was breeding “two great classes — tramps and millionaires.”

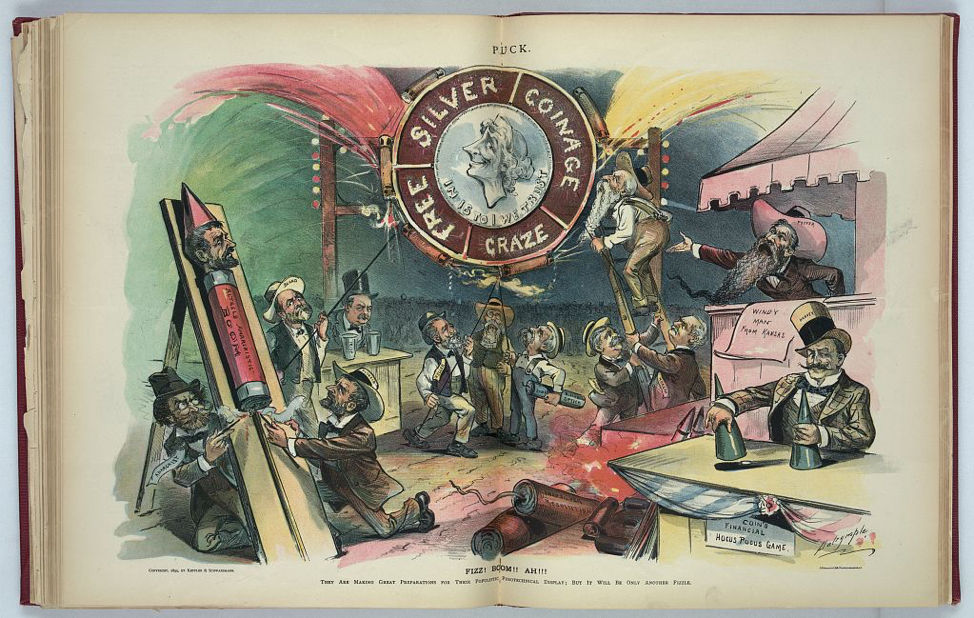

Their Omaha Platform offered several ideas to correct the imbalance of power between farmers and bankers. One of the key ideas was “free silver.”

Farmers believed their problems stemmed from a shortage of circulating money. At the time, the Treasury Department only issued currency that was backed by gold. Rural voters wanted to expand the money supply through unlimited silver coinage.

Republicans determinedly opposed this. Accepting silver coinage on par with gold-backed currency would lower the value of the American dollar, they believed. And increasing the money supply would lead to inflation, which would reduce the earnings on the mortgages bankers held.

The Populists had plans beyond silver-backed dollars. For example, they proposed to eliminate private banks, to set up a federal loan program, enact public ownership of railroads, and create a system of government-run grain elevators to store their crops.

Big city journalists and political insiders felt only contempt for the Populists. They regarded them as ignorant, simple-minded yokels who wanted something for nothing, wild-eyed rubes who envied the success they couldn’t achieve.

This was how the Weekly Kansas Chief, in July 1896, described the Populists at their convention:

…anarchists, howlers, tramps, highwaymen, burglars, crazy men, wild-eyed men, men with unkempt and matted hair, men with long beards matted together with filth from their noses, men reeking with lice, men whose feet stank, and the odor from under whose arms would have knocked down a bull, brazen women, women with beards, women with voices like a gong, women with scrawny necks and dirty fingernails, women with their stockings out at the heels, women with snaggle-teeth, strumpets, rips, and women possessed of devils, gathered there, and sweltered and stank for a whole week, making speeches, quarrelling, and fighting like cats in a backyard.

In 1896, William Allen White, owner and editor of The Emporia Gazette, gained a national reputation for a scathing attack on populists, whom he held responsible for the shrinking prosperity in his state. In his article, “What’s the Matter With Kansas?” he called the Populists “gibbering idiots” who were making Kansas the laughing stock of the nation.

But voters of the farmland saw things differently. In the 1892 election, the Populist presidential candidate, James B. Weaver, won over a million votes. Several Congressmen, three governors, and hundreds of lower level officials in the Populist Party were also elected.

In Kansas, the Populists elected the governor, Lorenzo D. Lewelling, and the majority of the state senators.

They also claimed to have the majority in the House. But the victory wasn’t definitive. Several districts were contested. The Republicans claimed the majority was theirs. The Populists responded by charging the Republicans with election fraud. Neither would yield control of the House.

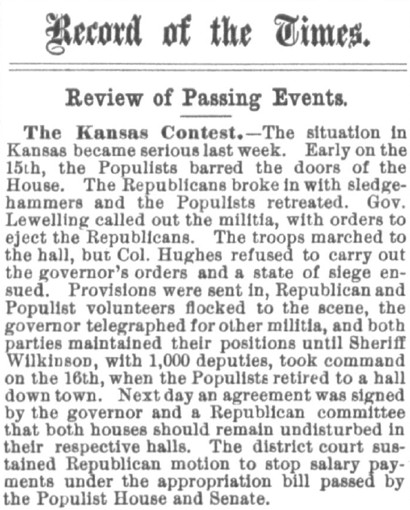

When the legislature reconvened on January 10, 1893, both parties named their officers and began conducting business. They held separate sessions in the same hall but at different times.

The matter dragged on into the next month. Then, on February 14, the Republicans took action. They subpoenaed a Populist official to testify before the Republican House about the past election. The official refused to honor the subpoena. The Republicans had him arrested. They also arrested the chief clerk of the Populist representatives.

Angered by this move, the Populists stormed the House, rescued their clerk, ejected the Republicans, and locked themselves inside the hall.

The next morning, the Republicans returned in force. They broke down the door with a sledge hammer and drove out the Populists.

An account of these events appeared in the Post’s sister publication, The Cultivator and Country Gentleman on February 23, 1893.

Governor Lewelling called out the militia and ordered its commanding officer to eject the Republicans. But the commander, a Col. Hughes, a staunch Republican, refused the order.

The next day, Sheriff Wilkinson and hundreds of armed deputies entered the capitol to support the Republicans.

Hoping to avoid bloodshed, the governor signed an agreement with the Republicans. They could continue their business in the Hall. The Populists would meet elsewhere in the city.

Both parties continued to act as the state’s House of Representatives for the next eight days. Then the Kansas Supreme Court decided the Republicans had won the House in a 2 to 1 decision. The Populist momentum began a long decline. The Populists won several elections, but by 1908 it had faded into history.

Despite its failures, the party made a lasting impression on American society. They had introduced ideas like the eight-hour workday, a graduated income tax, and the use of secret ballots, free rural mail delivery, a primary election law, women’s suffrage, regulation of railroads, supervision of stock and bond transactions, and direct election of U.S. senators. All had been championed by the Populists.

In time, William Allen White felt a little ashamed of his “What’s the Matter with Kansas” article. It had been too easy to attack the Populists who lacked the education, connections, or money to improve their undeniably harsh lives.

In an August 1, 1914, Post article, writer Samuel G. Blythe offered a new appreciation of the Populists:

The mildest thing said about the Populists was that they were crazy; but they were the first to introduce as issues into the politics of this country the initiative, the referendum, the recall, the control of railroads, the regulation of freight rates… They were not crazy, except incidentally. They were prophetic. They saw ahead. They did not know how to get what they wanted and did not get it, but they had a pretty clear idea of what was needed and what was coming.