The Centennial of Mickey Rooney, America’s Most Persistent Performer

Today is the centennial of the birth of Mickey Rooney, the once-golden boy of Hollywood with likely the longest-running career of any American (or otherwise) film actor.

After beginning his lifelong stint in show business in a specially-tailored tux in his parents’ vaudeville shows at 15 months old, Rooney landed his first film role at age 6 and didn’t stop until 2014, the year he passed away.

The America of Rooney’s films at the height of his celebrity – when he played the lovably well-intentioned troublemaker Andy Hardy in 16 movies – was The Saturday Evening Post’s America: one with a freshly-ironed moral fabric and joyful endings. In fact, Rooney was a Post boy. As the Post bragged in a short piece in 1942, the actor won a medal at age 13 for selling magazines door-to-door and even at the studios where he made his Mickey McGuire movies: “Andy Hardy, as portrayed by Rooney, more often than not engages in financial enterprises that backfire, but in real life Rooney got away to a fast business start with no adolescent detours.”

The Post’s coverage of Rooney wasn’t always so laudatory, however. By 1962, he was just another example of “moral decay in America” as an editorial shone light on his multiple nasty divorces and thousands in back taxes. “Nothing in this sad story surprises us, Hollywood being the way it is,” the Post printed, “but we remember Andy Hardy.”

The now-familiar arc of the innocent child star becoming a frighteningly flawed adult perhaps began with Rooney’s departure from the saccharine cinema of the Hardy family into the trappings of wealth and fame. But he couldn’t play Andy Hardy forever, and he didn’t want to.

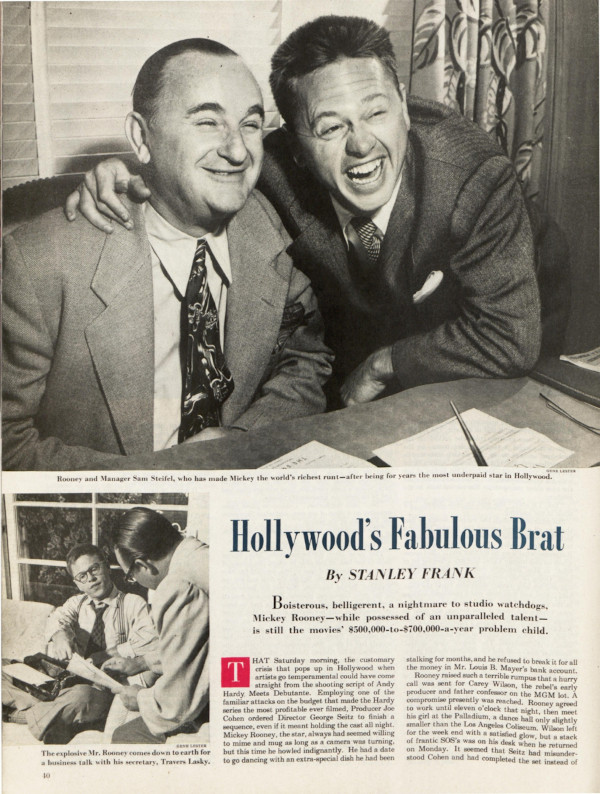

In 1947, the year after Rooney’s last film as Andy Hardy (with the exception of the 1958 revival), the Post published a lengthy profile of the actor called “Hollywood’s Fabulous Brat.” Rooney had spent three years – 1939, ’40, and ’41 – as the biggest box office draw in Hollywood, and he had a reputation for being belligerent, on the set and off. He was also seeking more substantial work.

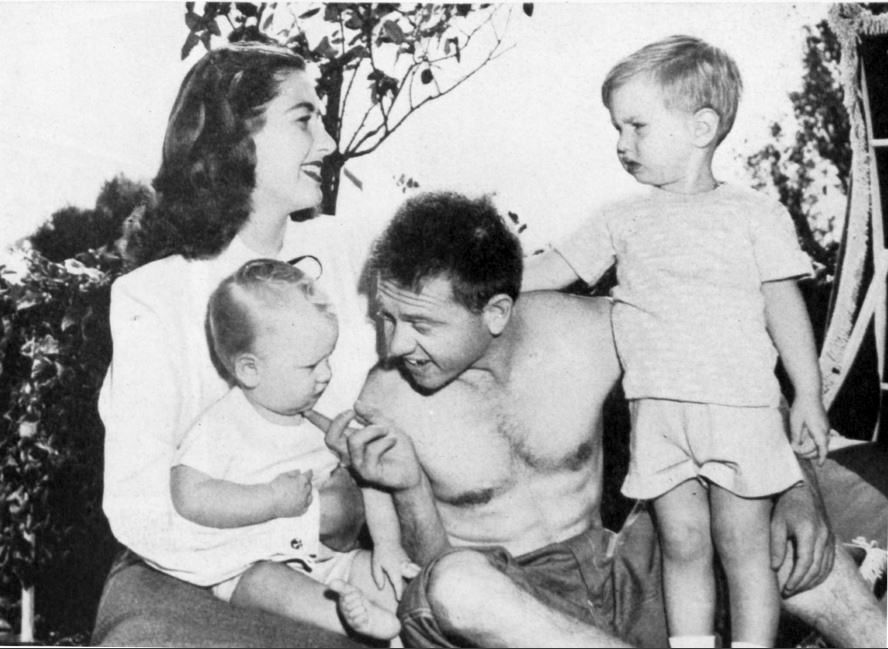

“I’ll never make another Hardy picture,” he told the Post, incorrectly. “I’m fed up with those dopey, insipid parts. How long can a guy play a jerk kid? I’m 27 years old. I’ve been divorced once and separated from my second wife. I have two boys of my own. I spent almost two years in the Army. It’s time Judge Hardy went out and bought me a double-breasted suit. With long pants.”

Rooney wanted to stretch his wings as he had when he played Puck in Warner Brothers’ A Midsummer Night’s Dream in 1935, when The New York Times reviewed his “remarkable performance” as “one of the major delights of the work.” He wanted to enter into a new chapter of complex films like the forthcoming gritty boxing drama Killer McCoy and the Eugene O’Neill-adapted musical Summer Holiday. After the decades-long run of Hardy family movies and musicals with Judy Garland, however, Rooney’s box office draw dwindled.

Since conquering the motion picture industry with nothing but talent and grit, Rooney couldn’t have foreseen a future where he wasn’t at the top. He imagined he could reinvent his career with the same momentum he always had. As Nancy Jo Sales wrote in Vanity Fair after Rooney died in 2014, “his career suffered from his juvenile appearance, and his diminutive height — he wasn’t a boy anymore, and he wasn’t a leading man, so where did he fit in? — but he never gave up.” Rooney kept making films into the 21st century, delivering memorable performances in movies like The Black Stallion and It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World. In 1979, he took on Broadway in the successful revue Sugar Babies, spawning years of tours.

Rooney’s undeniable talent steered him toward a lifelong commitment to entertainment. Given his start in the demanding realms of vaudeville and the old Hollywood studio system, the performer never hesitated to master new skills, like banjo-playing or crying on demand, to satisfy his audience. This was perhaps never more true than in 1941, when Rooney performed at President Roosevelt’s Inauguration Gala.

Alongside talents like Charlie Chaplin, Ethel Barrymore, and Irving Berlin, Rooney was expected to contribute an act of celebrity impersonations. He had a better idea: he would play his three-movement symphony Melodante on piano instead. As the Post reported, “The audience of 3,844 celebrities laughed when Rooney sat down at the piano that evening and shot his cuffs as he poised his hands over the keyboard.” They thought he was doing a bit. After he played the 19-minute score he had written himself, however, they burst into applause.

For Rooney, the label “triple threat” was an understatement. Starting from a poor broken home, he gave everything he had to build his iconic career, but it never turned out exactly the way he wanted. “People look at me and say, ‘There’s a lucky bum who got all the breaks,’” he said in 1947, “Yeah, I got the breaks — all in the neck.”

Featured image: Gene Lester, The Saturday Evening Post, December 6, 1947

Remember Post Boys and Post Girls?

Our Saturday Evening Post newsboys were crackerjack salesmen, according to the September 1909 news booklet printed to encourage these young entrepreneurs. These were compilations of success stories, jokes, and sales tips for Post newsboys.

“George Blount put a Saturday Evening Post advertisement on the biggest elephant in a circus parade,” boasted the editors in the 1909 newsletter. We’re not sure how George accomplished this task, but he apparently came away unscathed. But Kenneth Casselman of British Columbia did George one better when he “created a big sensation at a local roller-skating carnival by wearing a Saturday Evening Post suit. The trousers were made of oilcloth Post signs and the coat and cap were covered with front covers of recent issues of the Post.” Score one for creativity.

In the 1930s, “I had a route and delivered the Post at 5 cents a piece to five to 25 customers,” Robert Bonney of Peoria, Illinois wrote us in January of this year. “I got to keep 1.5 cents a copy,” which he put in his bank account. In 1936 “I entered the University of Maine and used my bank account to help pay my way.”

We’ve been privileged to hear from many of the former Post boys over the years and have often run photos of them in the magazine’s Letters to the Editor. We’ve also discovered that regular Saturday Evening Post contributor Charles Osgood was once a Post newsboy. And guess what else we’ve found out? Not all Post newsboys were boys.

Take the case of 10-year-old entrepreneur, Mary Simmons, of Portland, Oregon. We’re fortunate to have a great photo of Mary on her rounds from 1927 because, according to her son, David, she made a sale to a professional photographer, and “he asked her if she would step outside and pose for this picture.”

Like other “newsboys,” Mary gained some business savvy from her route. Her father died six years later, and the children had to run his carbon paper business. “My mother at age 16 drove a Model T all over eastern Oregon selling carbon paper, camping with a tent to save money,” David Powers e-mailed us.

Like other young sellers, Mary had to work hard to earn her $10 a week toward college. But there were perks, too. Van Duyn candies later became famous, but Mary recalled seeing Mr. Van Duyn making candy himself. “I could barely see over the big copper kettle,” she later told her son. “I could see him dump the butter in and smell the candy. Best of all was that the candy that was not perfect, I got to eat.”

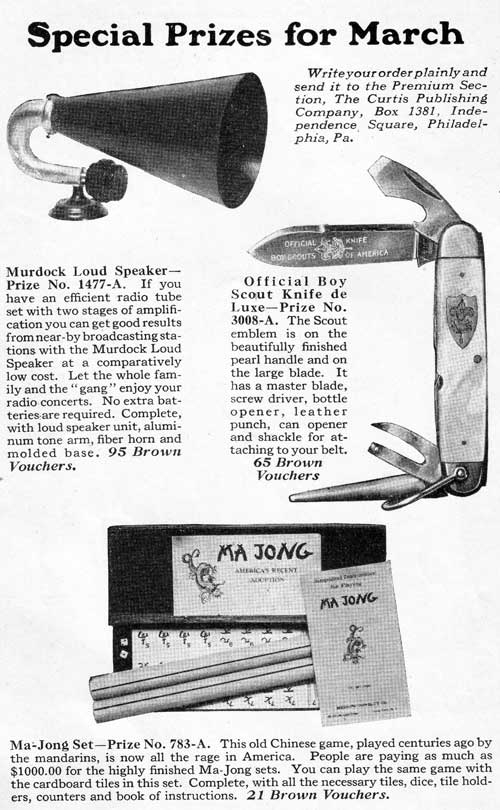

OK, free candy was important. Even more exciting was the cool stuff you could earn with your sales vouchers. This ad from 1924 shows a Ma Jong set (with cardboard tiles), a great Boy Scout knife and, if you had as many as 95 “brown vouchers,” you could get this loud speaker. “Let the whole family and the ‘gang’ enjoy your radio concerts.” A dude (or dudette) couldn’t be more happening than that.