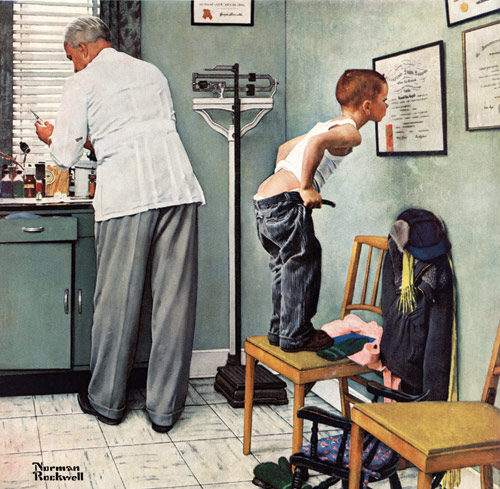

The Rockwell Files: Pain in the Rear

When Norman Rockwell was planning this iconic Post cover, he spent a certain amount of time considering how much of the boy’s derriere to show.

Too much cheek would be considered rude, and too little wouldn’t be funny. He discussed it with friends and family and finally settled for this half-up, half-down compromise.

Later that same year, the same young model, Eddie Locke, would pose alongside a state policeman for Rockwell’s Runaway cover.

As an adult, Eddie was asked what his boyhood friends thought of his modeling for the Post.

“You know,” he replied, “when you’re sitting with a police officer, that’s one thing. When you’re posing with your pants down, that’s quite another.”

Classic Covers: Father’s Day, 1950s Style

Enter the prosperous 1950s, when Dad was king of his suburban castle. The nuclear family had followed the new interstate system right out of the city and settled into small communities of manicured lawns, picture windows, and Sunday barbecues. And Dad outside the city limits proved to be a perfect character for the situational comedies portrayed on Post covers. Join us in a fun look at ’50s dads (or should we say daddy-os?). They just may remind you of someone you love.

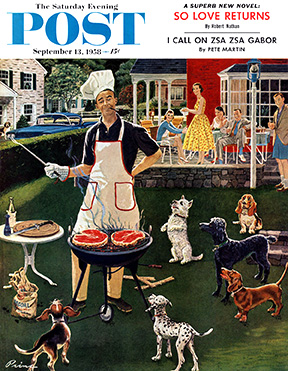

Pop vs. Pup

Ben Prins

September 13, 1958

© SEPS

Sending out smoke signals has made this dad popular with more than just his family. Artist Ben Prins got the idea for the cover while outside feeding his children’s three cats. Post editors wrote that dogs would “drop around to pass the time of day” during chow time at the Prins residence.

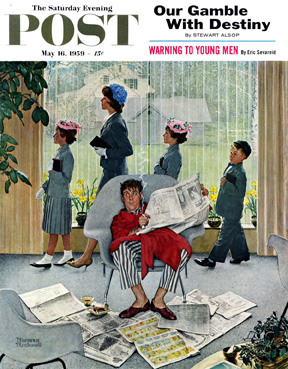

Bad Dad

Norman Rockwell

May 16, 1959

© SEPS

“This is my favorite Post cover for Father’s Day,” emailed reader Bob McGowan of California. “It’s best known as Sunday Morning, but I’ve nicknamed it ‘Bad Dad,’ as he knows he should be dressed in his Sunday best, also headed out the door to church with Mom and the youngsters.” [See how to get your favorite covers featured below.]

Rockwell’s obsession with detail shows in this 1959 cover. He went to several furniture stores until he found just the right chair for this “bad dad” to slink in. And, if you click on the image for a close-up view, you’ll see a more mischievous detail: The artist arranged “horns” into the sinner’s disheveled hair.

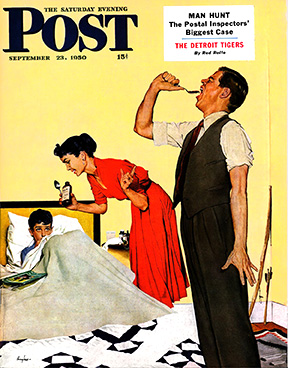

Father Figure

George Hughes

September 23, 1950

© SEPS

Is there no sacrifice too great for Dad? The problem with proving that the medicine is not so repulsive is that Pop is a lousy actor. Even without the giveaway expression, editors noted, “Junior wouldn’t have fallen for the treachery. Every youngster learns at the dinner table to mistrust what his parents say tastes fine until he finds out for himself.” Artist George Hughes, who did 115 Post covers, knew all about parental scams: He had five daughters.

Gone Daddy Gone

George Hughes

June 12, 1954

© SEPS

“It is heartwarming,” wrote Post editors of this Hughes cover, “to see how this boy trusts his father to halt that vehicle before both teacher and pupil land on their ears. It is heart-chilling to see how the father doesn’t.”

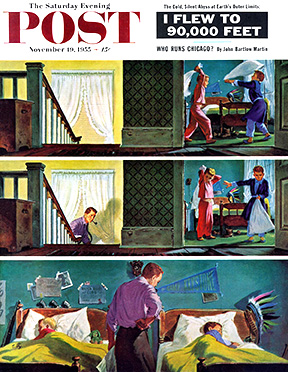

Father Knows Best?

Thornton Utz

November 19, 1955

© SEPS

“Old folks are so fussy about noises at night,” wrote Post editors of this 1955 cover. “They hear a burglar, and they grope downstairs, and there is none, or they hear a pillow fight, and grope upstairs, and there is none. If [artist] Thornton Utz’s father doesn’t stop fussing around, he’ll wake those boys up.” Right. This dad isn’t buying it; the readers aren’t buying it; and, admit it, neither did your dad.

Do you have a favorite Post cover? Tell us about it and we’ll feature it with your comments in an upcoming cover art piece! If you don’t know the date or artist, just give us a brief description. Send to [email protected].

See our collection of cover art here.

Art Licensing

For licensing information, please visit curtispublishing.com,

call 317-633-2070, or email [email protected].

Classic Covers: Firefighters

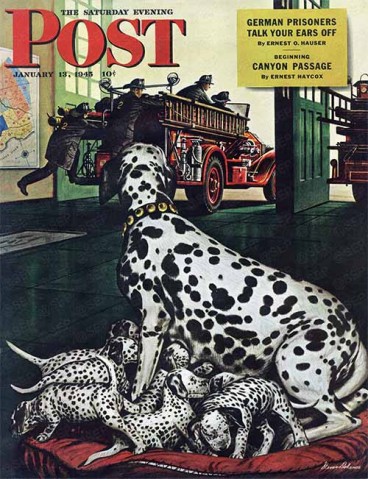

Dalmatian and Pups

Dalmation and Pups

by Stevan Dohanos

from January 13, 1945

Illustrator Stevan Dohanos visited his local firehouse in Westport, Connecticut, to get a permit for burning brush. There he met Patch the dalmatian and got an idea for a Post cover. Patch is only on the cover in spirit, however. Being a guy, he would have no ambivalence about staying with the kids; he would have just gone to the fire. The dog pictured in this cover was a pretty female at a Long Island kennel, complete with pups.

As to why dalmatians are associated with firefighters, there are many theories, most of which involve the dogs guiding the horses pulling the firewagons. Some say dalmatians in particular had a calming effect on horses, and others say their spotted coats were easy to see as the fire horses went thundering through the streets en route to the blaze (as in the cover below).

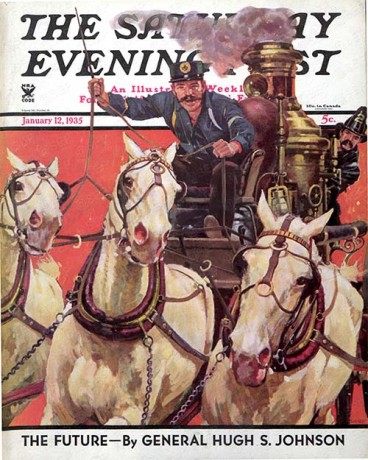

Racing to the Fire

Racing to the Fire

by Maurice Bower

from January 12, 1935

Maurice Bower illustrated numerous subjects for ads, books, and at least a dozen magazines, but he had a way of conveying the raw power and energy of horses. Even when this cover was published in 1935, it was a glimpse of firefighting efforts in a bygone era. Motorized fire trucks were becoming common by 1910.

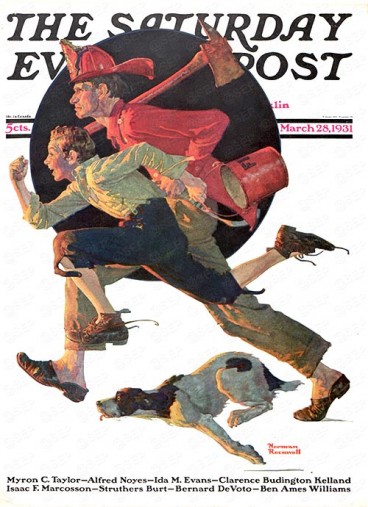

To the Rescue

To the Rescue

by Norman Rockwell

from March 28, 1931

From time to time, Norman Rockwell experimented with technique. This particular one was called “dynamic symmetry” and was supposed to be scientific, or some such newfangled notion to that effect. After this one, he did one more attempt using the same method and was disappointed with the results. He gave that painting to a cousin and reverted to his time-tested formulas, vowing never to stray again. Nonetheless, the cover does convey excitement and urgency.

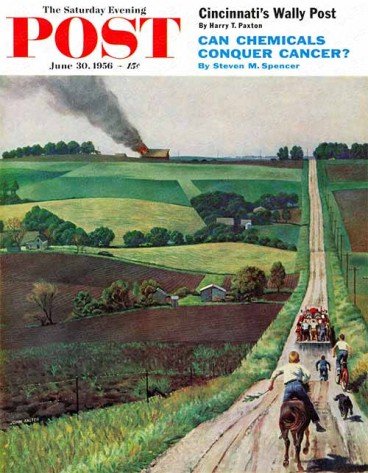

Chasing the Fire Truck

Chasing the Fire Truck

by John Falter

from June 30, 1956

This was a scene from little Johnny Falter’s Nebraska childhood, recreated in 1956 by grown-up artist John Falter—albeit with a more modern fire engine sure to save the barn.

As much as we love our illustrators, we sometimes find ourselves wondering what they were thinking when painting a cover. According to Post editors, three young “volunteer firefighters,” two on bike, and one on horseback, repeatedly careened downhill in their efforts to assist the artist, much to the astonishment of onlookers. All turned out well, and they made it to the imaginary fire in time.

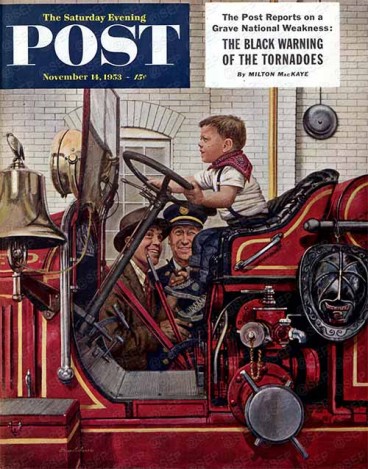

Boy on Fire Truck

Boy on Fire Truck

by Stevan Dohanos

from November 14, 1953

Behind the wheel of a bright red firetruck—a boy’s dream in 1953. During the ’40s and ’50s, Stevan Dohanos illustrated about 125 Post covers. Dohanos and Rockwell both depicted Americana; however, Dohanos was a ‘realist,’ unlike his friend, who tended to romanticize and idealize. Rockwell painted life as he would like it to be, whereas Dohanos “always gloried in finding the beauty in the ordinary things of life.”

It looks as if Dad wouldn’t mind a turn at the wheel himself.

Post cover reprints are available at Art.com.

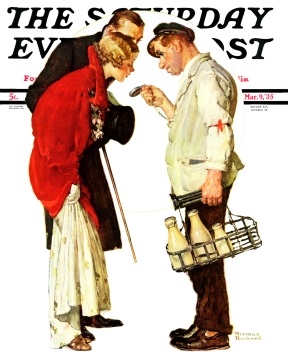

Overnight Sensation

Partygoers

Norman Rockwell

March 9, 1935

Get this framed at Art.com

The mere appearance on a Saturday Evening Post cover could be a springboard to fame. Such was the case for Terry Walker, who, after years of struggle in Hollywood, became a movie star after modeling for the Post cover shown here.

Until then, Walker’s only claim to fame was being cousin to Bobby “Wheezer” Hutchins of the Our Gang series. Walker, born Alice Norberg, grew up in the small fishing village of Petersburg, Alaska, then ran off to Hollywood at 14, first changing her name to Alice Doll.

She sang and danced in vaudeville shows, modeled shoes, and even worked with chimpanzees. She soon found a niche, of sorts; she was a good singer who could hit the high notes, so, as the talkies emerged, she became a stand-in “screamer” in horror films for better-known actresses who needed to spare their voices. Her specialty was not to last: Producers soon realized that they could save recorded screams and dub them in later.

It was around this time that she changed her name once again to Terry Walker and was chosen by Norman Rockwell for this March 9, 1935, Post cover featuring a milkman pointing out the time to a couple that has clearly had a long night out.

When the issue hit the newsstands, the unknown actress miraculously transformed from a nobody to an “it” girl in Hollywood. Trouble was, she didn’t know it. Paramount executives frantically contacted Rockwell, but, unfortunately, the address he had for her was no longer current (and Google didn’t yet exist!). Studio officials traveled to Alaska, back to Hollywood, then to New York City, and finally to Miami Beach, where they eventually found her singing with the Jan Rubini Orchestra at the Royal Palm Hotel.

It had taken 11 months to find her! But such are the nature of “overnight sensations” in Hollywood, even today. In fact, if you add it all up, it was a full 19 years from the day she left Alaska that Walker emerged as a Paramount star. She would go on to make 16 movies, including several starring roles. Her last picture was the 1944 Voodoo Man with Bela Lugosi.

Classic Covers: Rain, Rain, Go Away!

American poet and educator Henry Wadsworth Longfellow perhaps said it best: “Into each life some rain must fall, some days must be dark and dreary.” The rainy days on our Post covers show the dark and dreary, the frustrations along with the humor that accompanies a downpour. No fair weather friends, our cover artists!

Dating Rule No. 1: If trying to impress a girl with your fancy convertible, be sure a downpour isn’t in the works. In Albert W. Hampson’s 1936 cover, the young lady is clearly not impressed—whatever the make or model—when the rain comes. The expression on the young man’s face clearly says, “I have so blown it.” Well, at least she wasn’t wearing a lovely hat to ruin, such as the pretty lady in Douglass Crockwell’s April 8, 1939, cover. But she’s a clever lass—she’s pulling down the handy Post cover for protection!

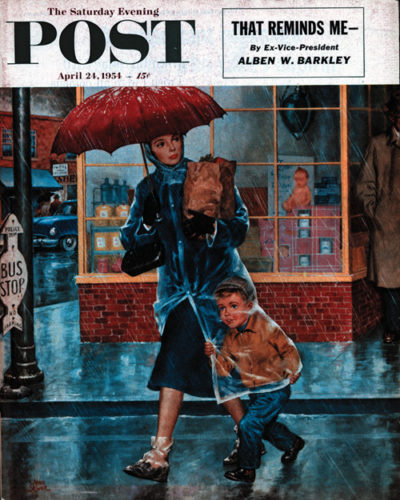

Boy Walking Under Mother's Raincoat

April 24, 1954

Also showing good ol’ American ingenuity is the young boy on Amos Sewell’s April 24, 1954, cover. Since mom’s raincoat is clear plastic, he figured out a way to walk in the rain, see where he’s going, and keep himself quite dry—well, at least the top half.

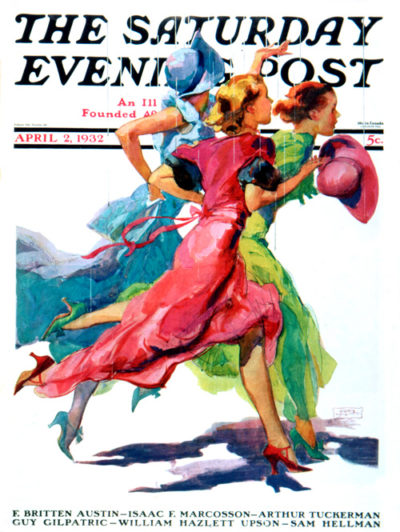

Downpours help us discover speed we didn’t know we had. In the 1950s, you not only worried about getting the top up on your convertible when a Midwest storm blew in, you had to scurry to get the laundry off the line. Artist John Falter remembered the “hair-curling lightning and thunder” in that part of the country from his boyhood, and his April 26, 1952, cover shows that Mother Nature clearly plans to take no prisoners. Also dodging raindrops are three charming ladies on John LaGatta’s colorful April 2, 1932, cover.

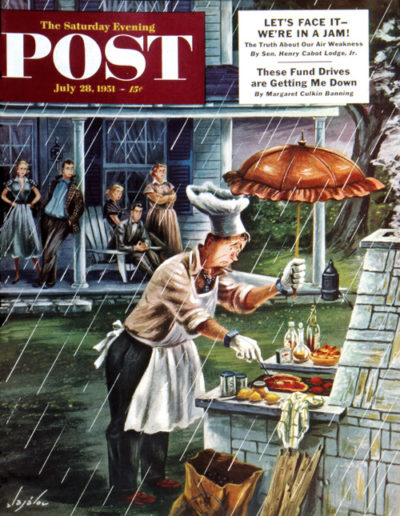

Constantin Alajalov

July 2, 1955

Let’s visit the local drive-in. Or is it the local float-in? On John Falter’s May 13, 1961, cover, our real-life hero protects burgers and shakes from the pouring rain as he scurries through the puddles to nourish his hungry troops. Rain or shine, the show must go on! Much more difficult than negotiating puddles to feed the family is cooking food in the rain, as seen in Constantin Alajalov’s July 1951 cover. You would think one of the slackers on the porch would at least hold the umbrella for the poor cook.

Ladies Running From Rain

April 2, 1932

Sarah Stilwell-Weber, who delighted Post readers in the early 1900s with her beautiful paintings of children, shows a girl walking in the rain, balancing schoolbooks and an umbrella on the October 9, 1909, cover. Having less luck with his umbrella is the gentleman in Robert Robinson’s March 18, 1911, cover. Holding on to your hat and an inside-out umbrella at the same time takes dexterity.

Another trio of beautifully dressed LaGatta ladies are getting splashed by a passing car in the May 20, 1939, cover. But leave it to a Post cover artist to find irony, as in one of our favorite rainy-day covers from October 2, 1948. Three pedestrians are being splashed by a passing truck. But not just any truck, dear friends, a delivery vehicle for the local dry cleaners.

On the bright side, our cover research found someone happy about the storms! Stevan Dohanos’ April 1946 cover shows gentlemen from the New York weather bureau delightedly noting the lightning storm outside. While there’s no fun getting wet, there’s a certain pleasure in getting it right!

Gallery

Girl with Schoolbooks in Rain

October 9, 1909

Man with Inside-out Umbrella

March 18, 1911

Ladies Running From Rain

April 2, 1932

Couple in Convertible

August 29, 1936

Lady in Hat in Rain

April 8, 1939

Ladies Getting Splashed

May 20, 1939

Weatherman Was Right

April 27, 1946

Splashed by Dry Cleaning Truck

October 2, 1948

Rainy Barbeque

July 2, 1955

Storm Coming

April 26, 1952

Boy Walking Under Mother’s Raincoat

April 24, 1954

Rain on the Boardwalk

July 2, 1955

Rainy Drive-In

May 31, 1961

Norman Rockwell: America’s Favorite Illustrator

In his warm, witty, and utterly candid autobiography, first published in 1960, the beloved artist offered Post readers a glimpse into his life and the often mischievous world around him.

When I was ten years old, a skinny kid with a long neck and narrow shoulders, I wanted to be a weight lifter. So I began a program of exercises to strengthen myself. Every morning I would do pushups, deep knee bends, jumping jacks, and the like before my bedroom mirror. After a month or so, unable to detect any improvement, I gave up. Instead of becoming a weight lifter, I decided to fall back on what seemed to be my only talent — drawing. And here I am, 56 years later, still drawing.

Every so often, usually when I’m having trouble with a picture, I spread on my studio floor reproductions of the 306 Post covers I have painted since 1916, walk around them, and try to decide whether my work has progressed through all those years. If it hasn’t, I say to myself, I’m washed up.

I never seem able to decide whether my work has improved, because my memories keep intruding. Looking at all those covers, I recall their history: the models I used, the trouble I had getting the original idea, how the public reacted. Everything I have ever seen or done has gone into my pictures in one way or another. The story of my life is really the story of my pictures and how I made them.

There was my uncle, Gil Waughlum, for example, a well-to-do elderly gentleman, who in his youth had been something of a scientist and inventor. It was always told with pride in my family that Uncle Gil, in the course of one of his experiments, had flown the great Gil Waughlum kite from a tower on Washington Square in New York. I don’t know what the experiment proved — something to do with Benjamin Franklin and electricity, I believe — but it was important, for in their day Gil Waughlum and the great Gil Waughlum kite were well known.

When I knew him he had given up science. A stout old gentleman with pink cheeks and a bald head, he was always giggling and nudging my brother Jarvis and me to make sure we were properly merry. Whenever I think of him, I’m reminded of Mister Dick, the kindly, gay simpleton who was Betsey Trotwood’s companion in Dickens’ David Copperfield. I don’t mean that Uncle Gil was a simpleton. He wasn’t. But he had one eccentricity — he got holidays mixed up.

On Christmas Day, with snow on the ground, Uncle Gil would bring firecrackers to celebrate the Fourth of July. On Easter he would bring us Christmas gifts; on Thanksgiving, chocolate rabbits. The next year we had firecrackers on my birthday and chocolate rabbits for Christmas. We never knew what to expect. I always wondered where he got firecrackers in December or Christmas cards in April. But I guess the merchants in Yonkers, his hometown, understood his problem.

He always sneaked into the house and hid our gifts — under pillows, behind the couch in the parlor, in dresser drawers — so that we might have the fun of a treasure hunt. I remember him shouting, “Warm. Norman, warm!” as I approached a hidden present, and “Hurrah!” when I found it. In 1936, when I painted a Post cover of a small boy searching the pockets of his grandfather’s overcoat for a gift, I was really painting Uncle Gil.

Of course, I don’t claim to have put on canvas 66 years’ worth of people, places, and events. Rather, I store up things in my mind, and when I need something for a picture—a feeling, a character, a wry smile—there it is. And I draw it out and paint it.

Whenever I want embarrassment, I think of the time I tried, and for several agonizing minutes failed, to lift a 250-pound soprano during a performance at the Metropolitan Opera. For rackety-bang confusion, I recall my early days as an illustrator, when my models were surly dogs, rambunctious children, and a cheerful duck. Whenever I want despair, I remember the time I was swindled out of $10,000. For chagrin I remember my flops — the affair of me and the seven movie stars; the United Nations picture I couldn’t bring off.

And for a mixture of embarrassment, confusion, despair, and chagrin I recall my dinner at the White House. Come to think of it, that dinner embraces vanity, exuberance, fright, and a wonderful, warm personality. It’s too complex to paint; it wouldn’t fit inside a frame.

It all began one sunny day in May 1955, when I received a note from President Eisenhower, inviting me to a stag dinner at the White House. I had painted his portrait in 1952, but I had never expected an invitation to dinner. Overcome with delight and anxiety, I posted my acceptance and hurried to the attic to dig out my tuxedo. As I pulled it from a steamer trunk, a cloud of moths flew up. The sleeves were tattered, the seat ragged, the lapels threadbare. Hastening to a local haberdasher for a replacement, I was shown a midnight blue jacket with lapels dropping in a fat, glittering curve to the waist. I thought it looked cheap.

“You’re sure it’s fashionable?” I asked.

“Oh, yes,” said the clerk, “midnight blue, shawl collar — that’s the latest.” So, in spite of my misgivings, I bought it.

That wasn’t the end of my preparations. I expected to be nervous, even scared, at the dinner. Suppose my mouth dried up and I was unable to speak? What then? I thought. Why, you’ll be ashamed of yourself. (“Hello,” says the President — “Gargle,” say I.)

I visited the office of my friend, Dr. Donald Campbell. Could medical science help me? It could. Doctor Campbell handed me a tranquilizer pill. “Take it 20 minutes before you go to the White House,” he said, “and you won’t be afraid of a thing, Norman. It obliterates apprehension, tension, and dread.”

Armed with my pill (pea green) and my tuxedo (midnight blue) I went to Washington, confident that I was bulwarked against catastrophe. On arriving at my hotel I inquired how long it took to drive to the White House. Then I went to my room and worked out a schedule. At 6:30, exactly one hour before the dinner, I gave my tuxedo to the valet to press. At 7:00 he brought it back. As I fumbled for a tip, I noticed him looking at the tuxedo queerly.

“What’s the matter?” I asked.

“Nothing, sir, nothing,” he said, recovering the blank stare of valets waiting for a tip.

“The tux isn’t fashionable, is it?”

“Well, sir,” said the valet, “I might say that I have never seen that particular shade of blue before.”

When he had left, I stared morosely at my reflection in the shiny lapels of the tuxedo. Patting the pillbox in my coat pocket, I thought, At least you’ve got that; you may look like a fool, but you’ll feel like Grant at Appomattox.

I went into the bathroom, drew a glass of water, and shook the pill out of its box into my hand. It fell on its edge, rolled into the sink, and went down the drain.

“In 15 years,” I said out loud, “I’ll laugh at that.” Stunned, I went into the bedroom, put on my extraordinary tux, tied my tie, and went downstairs.

As I reached the taxi stand outside the hotel, a battered old cab chugged up, clanking and rattling. At the wheel was a stout, middle-aged woman with a chauffeur’s cap cocked over one eye. The doorman waved her away, but I signaled her to stop, feeling that we two, the cab and I, victims of adversity, should stick together.

“The White House,” I said.

“My land!” she exploded heartily. “You going to the White House? Whatta you going to do there?”

“I’m going to dinner,” I said, cheered by this onslaught of good nature.

“Wow!” she exclaimed. “I’ve never taken nobody to the White House before. I’ll get ya there in five minutes flat.” The cab leaped forward with a roar like a wounded rhinoceros.

“Wait!” I said. “I don’t want to be early. We’d better go to the White House and then drive back and forth in front of it until the dot of 7:30.”

“O.K., mister,” she said.

While we were cruising up and down Pennsylvania Avenue she asked, “What’s your name? You famous?”

“I do covers for The Saturday Evening Post,” I said. “My name’s Norman Rockwell.”

“Are you scared?”

“Yes,” I said, studying my watch. “Get ready now. It’s almost time…. Now!”

We turned into the White House gate and jolted to a stop. The guards checked my invitation. Continuing up the drive, we waited while a chauffeur helped a gentleman out of a limousine. A crowd of Secret Service men and other functionaries were standing at the entrance. I paid my fare and started up the steps. “Hey, Mr. Rockwell,” boomed a voice behind me. I turned around. The cab driver was waving at me. “Good luck, Mr. Rockwell!” she shouted. “Good luck!” The Secret Service men laughed. I waved back. “Thanks,” I called.

{mospagebreak}

Rockwell_Eisenhower.jpg

A secretary ushered me upstairs and into a sitting room. I almost panicked as I crossed the threshold, for all the tuxedoes were black, with dull lapels. A minute later President Eisenhower greeted me warmly, and I felt right at home.

Then the President, raising his voice a trifle, explained to all of us that his stag dinners are informal get-togethers; he hoped we would not talk to the press about the dinner. So I will only say that I had a fine, easy time and enjoyed myself very much.

After leaving the President, as we were standing on the steps of the White House, we sounded like a bunch of kids discussing the high school football hero. A secretary had told us that our evening had lasted one-half hour longer than any of the President’s other informal evenings. We were delighted and flattered, which shows how President Eisenhower affects people. You just can’t help liking him.

I have one dark confession to make. Before each place at the dinner table was a small jackknife, a gift from the President to each guest. There was no inscription on the knife, however, so I went to a jeweler’s in New York the next day and asked to have “From DDE to NR” engraved on the knife. During the next few months, whenever I took out my knife, always being careful to show the inscription, people would say, “DDE? Is that President Eisenhower? Where’d you get that knife?” So I’d get a chance to describe my evening at the White House. Ah, vanity, vanity, thy name is Norman!

I sometimes wonder why I was so nervous at the prospect of dining at the White House. After all, I’m no pink-cheeked innocent. Still, I have a rather simple view of life. To me, a President is an awe-inspiring figure. I can’t be as cool as a clam at the prospect of dining at the White House.

And then I have a mercurial temperament. When that pill rolled down the drain, my spirits followed. The same sort of thing happens with my work. When the art critics call me “cornball” and my work “kitsch,” which I’m told is a derogatory term for popular art, I begin to worry. But I always pick up my brushes and go back to work. For better or for worse, I’ll never be a fine arts painter or a modern artist. I’m an illustrator, which is very different.

The modern artist and the fine arts painter have only to satisfy themselves. The illustrator must satisfy his client as well as himself. He must express a specific idea so that everybody will understand it. He must meet deadlines. The proportions of the picture must always fit the proportions of the magazine.

Ten or fifteen years ago a Bohemian art student — beard, long hair, sandals — kept hanging around a studio I had rented in Provincetown, Massachusetts. One day he interrupted my work on a painting of Johnny Appleseed — an old man with an iron kettle on his head and a burlap sack for a coat, striding across a hilltop, flinging out handfuls of seed.

“Whatta ya do it that way for?” the art student asked.

“What do you mean?”

“Whyn’t ya do it with more feeling?” he said. “Like this.” He pulled some colored chalk out of his pocket and outlined a tall rectangle on a big piece of paper. “Now,” he said, filling in with light-brown chalk a shape like a hawk’s beak, “that’s old Johnny’s body. It was browned by the wind and sun. O.K.?”

I nodded, startled,

“O.K.,” he said, and above the hawk’s beak, which projected from the lower right corner, he divided the rectangle into a red area and a white area, each roughly triangular. “He was kind of a religious fanatic,” he said. “Right?”

I nodded dumbly.

“So the white’s his spirit,” he said, “and the red’s the physical part of him, and they’re contending, the physical and the spiritual.” He rubbed blue chalk over the area below the hawk’s beak — “That’s nature.”— made the base of the rectangle dark brown —“That’s earth.”— and drew a hand casting a seed, the arm coming out of the hawk’s beak.

“But,” I said when he’d finished, “nobody knows it’s Johnny Appleseed. Only you know it’s Johnny Appleseed. Nobody else can tell who it is.”

“So? What difference does it make about anybody else? I know it’s old Johnny. I’m painting it for myself. Who cares about the unwashed masses?”

“Besides,” I said, “your picture won’t fit into the book it’s supposed to appear in. The proportions are wrong. You’ve got it too tall.”

“So make the book tall,” he said.

All of which demonstrates, I think, that a modern artist or fine arts painter doesn’t go at a picture the same way an illustrator does. I believe strongly that a painting should communicate something to large numbers of people. So, according to some critics, my work is old-fashioned, trite, banal. This criticism worries me now and then, especially when a picture I’m trying to finish is going badly, but I’ve learned that I can’t change. I’m not a modern artist and never will be. I don’t see things the way modernists do, even though I enjoy studying their work. I’ve been an illustrator since I was 16 years old. I’m not particularly satisfied with my work — at least I’m always trying to improve it — but I believe in it.

It’s not that painting Post covers is easy. I haven’t been doing it for 43 years just because it was the simplest way to earn a living. It’s been darned difficult at times. Once I couldn’t finish a picture for six months; I almost went under that time. And there is a recurring crisis when I seek Post cover ideas.

During my first years as an illustrator, when I’d sit down in the evening to think up a batch of new ideas I’d feel all washed out, blank, nothing in my head but a low buzzing noise. I’d stare at the wall and doodle. One day, after I’d been aimlessly sketching and crumpling up sheets of paper for hours, I said to myself, This has got to stop; I can’t sit here and muse all day. So I figured out a system and used it for 20 years or so.

When I had run out of ideas, I’d eat a light meal, sharpen 20 pencils, and lay out a dozen pads of paper on the dining room table. Then I’d draw a lamppost (after a while I got to be the best lamppost artist in America). Then I’d draw a drunken sailor leaning on the lamppost. I’d think about the sailor. Did his girl marry someone else while he was at sea? He’s stranded in a foreign port without money? No. I’d think of the sailor patching his clothes on shipboard. That would remind me of a mother darning her little boy’s pants. Well, what did she find in the pocket? A top. A knife handle. A turtle — I’d sketch a turtle slouching slowly along to —

Slowly. That would make me think of a kid going to school. No, it’s been done. How about the kid in school? Of course, he hates school. Gazes out the window at his dog. I’d sketch that. The dog runs after a cat. Cat climbs a tree. Dog ambles about, looking for trouble. Sees an old bum stealing a pie from a kitchen window. Dog latches onto the seat of his pants. I’d sketch that. Bum escapes. Eats the pie. Sheriff collars bum. I’d sketch that. Bum to jail….

I’d keep this up for three or four hours, the rough drawings piling up on the floor. Then, worn out, I’d arrive at the absolute conviction that I was dried up, through, finished. So I’d go to bed, completely discouraged.

The next morning I’d be desperate. After pawing at my breakfast eggs for a few minutes, I’d push them away and drag myself out to the studio. What was I going to do? No ideas. I’d kick my trash bucket and suddenly, as it rolled bumpety-bump across the floor, an idea would come to me like a flash of lightning. I’d given my brain such a beating the night before that it was in a sensitive state. Pretty soon I’d have a Post cover.

Nowadays I don’t think up ideas in exactly the same way, but the process is just as nerve-racking. You’d think that by this time I would have thought up a simple, efficient system, but I haven’t. A good idea for a Post cover is hard to come by. I have to work for it. But a picture is worth any amount of bother. I cling to this belief in spite of the trouble it’s got me into. Further on I’ll tell about how I bought almost all the old clothes in Hannibal, Missouri, because of it. And why I’d be embarrassed if I met Stan Musial, Van Johnson, Loretta Young, or Lassie on the street.

It’s a marvel to me the situations I’ve got into and out of during my life. When I was 15 years old, I taught French and athletics at a private school, though I couldn’t speak a word of French or play a slow game of tiddlywinks. Later on, my life was complicated by impostors who committed practical jokes — even swindles — in my name. Compounding confusion, my name is sometimes mistaken for that of Rockwell Kent, the noted artist, writer, and left wing sympathizer. But all these stories are for later telling. Right now, I guess, I’d better begin at the beginning.

I was born on February 3, 1894, in a shabby brownstone-front house on 103rd Street and Amsterdam Avenue in New York City. My mother was an Anglophile — I wore a black arm band for six weeks after Queen Victoria died — and she named me after Sir Norman Perceval, an English ancestor who reputedly kicked Guy Fawkes down the stairs of the Tower of London after he had tried to blow up the House of Lords. The line from Sir Norman to me is tortuous but unbroken, and my mother insisted that I always sign my name Norman Perceval Rockwell.

“You have a valiant heritage,” she said. “Never allow anyone to intimidate you or make you feel the least bit inferior. There has never been a tradesman in your family. You are descended from artists and gentlemen.”

But I had the notion that Perceval was a sissy name. I darn near died when a boy called me “Mercy Percy”; to my relief, the name didn’t stick. When I left home I dropped the Perceval immediately, despite my mother’s protestations.

Until I was nine or ten years old, my family spent every summer in the country at various farms, which took in boarders. The grown ups played croquet, or sat in high slat-backed rockers on the front porch. We kids were left to do just about anything we wanted. We helped with the milking, fished, swam, trapped birds, cats, turtles, and snakes, smoked corn silk behind the barn, fell off horses and out of lofts — did everything, in fact, that country boys do, except complain about the drudgery and boredom of farm life.

Those summers, as I look back on them now, more than 50 years later, have become a collection of random impressions outside of time, not connected with a specific place or event, and all together forming an image of sheer bliss. I remember throwing off my shoes and socks to wiggle my bare toes in the cool green grass on our first day in the country, then running off gingerly over gravel road and hay stubble for a swim in the river. I remember the hayrides, all the boarders singing as the horses trotted along the dark country lanes; the excitement of eating lunch with the threshing crew at long board tables; hunting bullfrogs with a scrap of red silk tied to the end of a pole; the turtles and frogs we carried back to the city in the fall, snuffling and crying on the train because summer was over.

During the summer I lived an idealized version of the life of a farm boy in the late nineteenth century, and my memories of those days had a lot to do with what I painted later on. Every artist has his own way of looking at life, and this view affects the treatment of his subject matter. Coles Phillips and I used to use the same girl as a model. She was attractive, almost beautiful. In his paintings Coles Phillips made her sexy, sophisticated, and wickedly beautiful. When I painted her, she became a nice, sensible girl, wholesome and rather drab.

This view of life I communicate in my pictures excludes the sordid and ugly. I paint life as I would like it to be. Somebody once said that I paint the kind of girls your mother would want you to marry.

In 1951, for the Thanksgiving issue of the Post, I painted a cover showing an old woman and a small boy saying grace in a shabby railroad restaurant. The people around them were staring, some surprised, some puzzled, some remembering their own childhood; but all were respectful. If you actually saw such a scene, some of the staring people would have been indifferent, some insulting and rude, and perhaps a few would have been angry. But I didn’t see it that way. I just naturally made the people respectful.

Frederic Remington painted the romantic, glamorous aspects of the West — cowboys sitting around a campfire, an attack on a stagecoach. Any old-timer can tell you that life in the wild West was often dull. But Remington, who was born and reared in upstate New York, didn’t find drudgery and boredom out West. In the same way I missed the dullness of farm life. I doubt that I would have idealized the country if I had grown up as a farm boy.

Maybe as I grew up and found that the world wasn’t the perfectly pleasant place I had thought it to be, I unconsciously decided to compensate. So I painted only the ideal aspects of life — pictures in which there were no drunken slatterns or self-centered mothers, in which, on the contrary, foxy grandpas played baseball with the kids and boys got up circuses in the back yard. If there were problems in this created world of mine, they were humorous problems. The people in my pictures aren’t mentally ill or deformed. The situations they get into are commonplace, everyday situations, not the agonizing crises and tangles of life.

The summers I spent in the country as a child became part of this idealized view of life. Of course, country people fit into my kind of picture better than city people. Their faces are more open and expressive, lacking the coldness of city faces. I guess I had a bad case of the American nostalgia for the clean, simple country life, as opposed to the complicated world of a city.

Then, I have other motives for painting as I do. For one thing, I have always wanted everybody to like my work, so I have painted pictures that I knew everyone would understand and like. I could never be satisfied with the approval of the critics; and, boy, I’ve certainly had to be satisfied without it.

Brush With Genius

While critics once dismissed Rockwell as merely an “illustrator,” art historians and collectors alike now celebrate his unique talents. The Post invited some well-known Rockwell collectors to share their thoughts about the artist’s universal appeal.

“Norman Rocwell was brilliant. He captured society’s ambitions and emotions and, more importantly, the cultural fantasy and the ideal of society during that particular time in American history. Through his illustrations, you get a sense of what Americans were thinking during those years, and of what was in their hearts.” — George Lucas

“Norman Rockwell’s work illustrated simple values, the pride of citizenship in the nation, in the community and in the home, and a truly American sense of ‘we’ll get through this’ in troubled times. From today’s point of view, you could claim that Rockwell idealized America and its citizens, but he also gave us images of poignant nostalgia and future promise.” — Steven Spielberg

“I first learned about Norman Rockwell while I was selling The Saturday Evening Post magazines door to door, when I was six years old. I admired his paintings of The Four Freedoms and A Scout Is Reverent. Years later I became interested in, and purchased his paintings of, the Homecoming Military Heroes at the end of World War II.

“My all-time favorite Norman Rockwell painting is Breaking Home Ties. This painting epitomizes the generation I grew up in, where parents made great sacrifices to see that their children were properly educated, by sending them to college.

“I had the privilege of meeting Mr. Rockwell and engaged him to paint a portrait of my son. Unfortunately, he passed away while the painting was still in progress. His staff sent me the unfinished copy of the painting.

“Norman Rockwell’s paintings truly capture the spirit of our country, including the very difficult times of the Depression and World War II.

“Prints and copies of his paintings are in my office, and I have the good fortune of viewing them every day.” — Ross Perot