Remembering Titan of Journalism Pete Hamill

Legendary journalist Pete Hamill died yesterday at age 85. The illustrious writer was described as a “quintessential New York journalist” for his decades of work in The New York Post, The Daily News, The Village Voice, Esquire, The New Yorker, Playboy, and The Saturday Evening Post. He published short stories and novels too, along with a memoir and books of essays.

In newspapers, Hamill became known for his plainspoken columns, giving on-the-ground perspective of culture and justice in his home city. For this magazine, he travelled Europe in the early ’60s, sending back celebrity profiles and stories of crime and labor disputes.

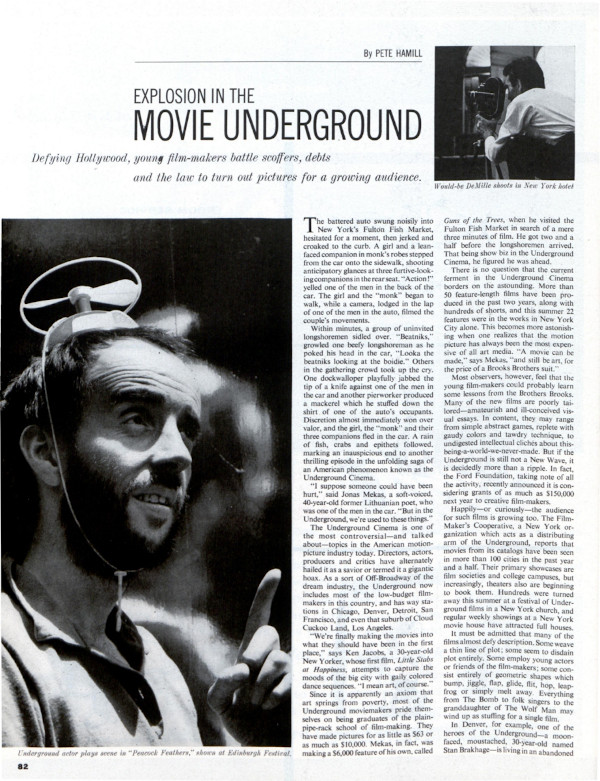

Hamill’s knack for skillfully undressing New York City was clear in one of his earliest stories for the Post, “Explosion in the Movie Underground,” printed on September 28, 1963. Years before the New Hollywood era of cinema was declared, Hamill documented the experimental filmmakers working on the streets of New York. He was skeptical of some of the “amateurish and ill-conceived visual essays” that were being produced, but he described the guerrilla directors and their makeshift moviemaking with the kind of sincere, closeup reporting that was a hallmark of his work.

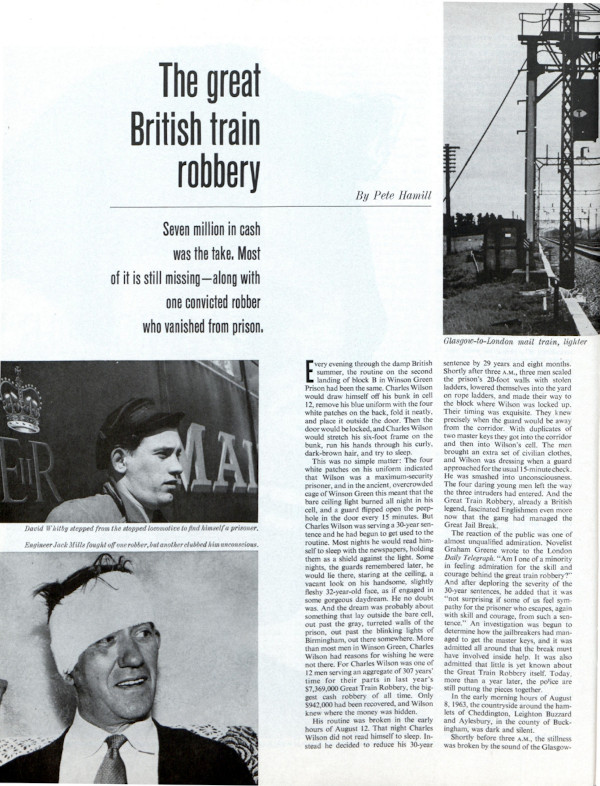

In another Post story, “The Great British Train Robbery” (September 19, 1964), Hamill covered the largest (at the time) cash robbery of all time, in which 15 men stopped a Royal Mail train and took off with more than 7 million dollars. He detailed the puzzling case of the 1963 Great Robbery and subsequent “Great Jail Break” that left British police scratching their heads and the public oddly impressed and intrigued.

Journalists and editors mourned Hamill’s passing. New York Daily News columnist Mike Lupica tweeted “As Pete once said of another New Yorker, it’s like a hundred guys just left the room,” and former New York Times writer Clyde Haberman tweeted “the world just became a far less interesting place.” Daily News reporter William Sherman wrote in an e-mail that Hamill was about the fastest writer he ever saw: “He had an preternatural understanding of the city and its people from the top hats on Fifth to the longshoremen on 12th at the River. He knew how to listen, which he advised us beginners as most important.”

In a phone call, Gay Talese recalled meeting Hamill while covering prizefighter José Torres in the late ’50s. “I’ve been living in New York for 75 of my 88 years,” he said. “I’ve known so many different writers, from poets to playwrights to journalists, and Hamill was a combination of all of those things, and he had the capacity for and time for friendship. I felt he was one of my best friends.” Talese said that Hamill’s life crisscrossed the lives of both the writing profession and nightlife: “I knew him when he was and wasn’t drinking and I couldn’t tell the difference because he was always a nice guy … he lived an extraordinary life.”

Hamill expressed his opinions on the Post in no uncertain terms soon after it folded in 1969 in a column in The Village Voice. He had visited the deserted offices on Lexington Avenue and gave a close account of the magazine’s downfall: criticism coupled with credit where credit was due for what he saw as the interesting work done in the ’60s. “At the end,” he wrote, “with the magazine collapsing around them, the Post editors finally saw fit to commission Norman Mailer to write something for them. It will never be printed by the Post.”

Hamill’s journalistic world of pounding out copy on a typewriter and throwing cigarette butts on the floor may be long over, but his intense passion for the truth, and his tendency to take to the streets to find it, is a lasting inspiration in every newsroom.

Featured image by David Shankbone, edited via the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license, GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2.

Addressing War in Wartime: Post Editorials from the 1940s

It is relatively easy to write memorials to America’s fallen in peaceful days.

But in war time, when your family, your relatives, or your friends are risking death every day in distant lands, you can’t rely on platitudes. In these two editorials, the Post writers tried to keep the big picture in focus, while acknowledge the intense worry and suffering of family members.

The Price of Freedom is High

from September 23, 1944

Those who have lost sons or husbands in this war inevitably resent statements that the casualties are “only” a fraction of what some extravagantly pessimistic people predicted they would be. In the homes which have been darkened by the death of a soldier, or which have welcomed back the shattered remnants of vigorous youth, the burden of war’s tragedy is little lightened by assurance that it might have been worse.

Already there is a heavy toll of sacrifice. On almost any street you pick can be found a home already visited by bereavement. There will be many more before the final accounting. Nevertheless, there are grounds for hope that the awful price will not be as great as many believed. The June invasion of France cost the United States 69,526 casualties, including 11,026 killed, as against the” half million casualties” freely predicted in certain quarter at home. The soldier in England who said to a visitor, “I don’t mind going over there, but I don’t want to be counted out in advance,” is at least vindicated by the result.

There is no cause for overconfidence. Undoubtedly there will be other Tarawas and Saipans in the Pacific. But the overall results so far makes it plain that the business of landing in enemy countries, preparatory to rolling ahead in a 1944 adaptation of the 1940 blitzkrieg, was accomplished with less loss of human life than even the most hopeful prophets believed was possible. For that fact, which in no way lightens the sorrows of the victims of war’s grim lottery, we can all be grateful.

For Many There Will be No Rejoicing

from March 3, 1945

The other day we received a letter which began this way:

“For many months I have eagerly read your articles about returning veterans and your stories about the resumption of life when our loved ones return from battle. Now my eyes search for other words — words of comfort, consolation and advice about how to carry on, knowing that that beloved husband will never return. Haven’t you a special word for us thousands of wives and mothers whose men have made the supreme sacrifice? Won’t you please make an urgent plea for a prayerful reception of the armistice that is to come? Wild and hilarious rejoicing will deeply hurt us, for we have had to pay such a great price for the victory.”

It would be easy enough to write a logical and philosophical reply to that letter, pointing out that grief is, after all, the common lot of man; that millions of others all over the world must shroud their relief at victory in mourning which will follow them to the grave; and that it is for the living to wear their sorrows proudly. But such a reply wouldn’t say much to the writer of the letter quoted above or to anybody who experiences the loneliness of bereavement. Not even the knowledge that the gallant husband who gave his life would want the news of peace received with joy can allay the bitter suspicion that one is surrounded by thoughtless and callous people who pluck the fruits of other men’s sacrifices, indifferent to the price which they paid.

We cannot answer this tragic letter, nor make the dread of the hilarity of heedless people easier for the writer to endure. But it is just possible that publication of this excerpt will point up the fact that a soldier’s name on a casualty list is not just a name, but represents a hurt which will never entirely heal; that the relatives of the men who have died in this war are a special charge on the kindness and decency of all of us; that now is particularly a time when “Teach me to feel another’s woe” should be the heartfelt prayer of everyone.