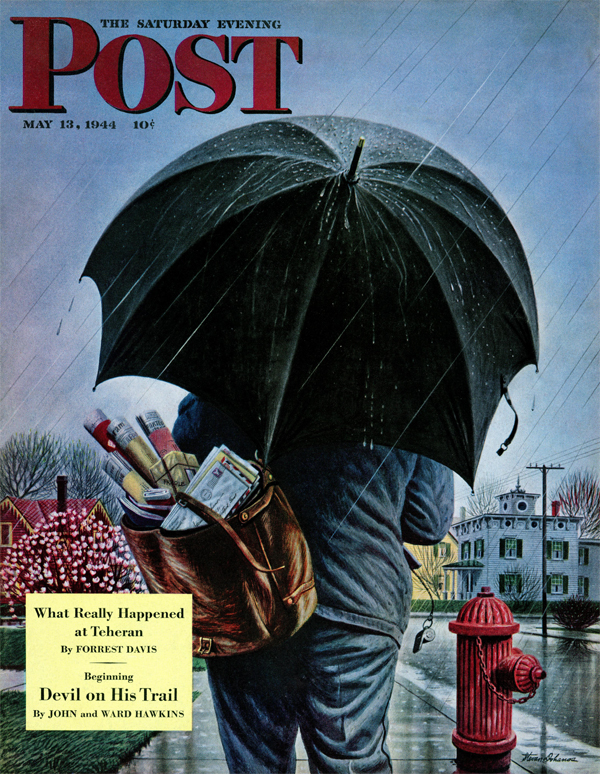

No More Saturday Mail?

In February 2013, the U.S. Postal Service proposed a plan to suspend mail delivery on Saturdays. After resistance from magazines, newspapers, and direct mail industries, the plan was revoked.

Ever since The Saturday Evening Post‘s first issue in 1821, we have been associated with Saturday delivery. In our early years, the issues were posted so that, at least in the Philadelphia area, they arrived on Saturday—specifically, with the second mail delivery of the day. Yes, the postal department made two deliveries of mail every day until 1950. However, it didn’t start delivering mail to homes until 1863. Prior to then, if you wanted your Post on a Saturday evening, you walked down to the post office and got it yourself. And if you craved the latest news, you might start reading your copy right where you stood, just as you might stop suddenly today to read the headlines on your smartphone.

We must make an important admission here: from the 1930s onward, the Post usually didn’t arrive on Saturday, but on Wednesday.

(Incidentally, the Postal Service proposed dropping Saturday delivery only after we redesigned our logo to emphasize “POST” and put “Saturday Evening” in smaller type.)

The Postal Service expects the suspension of Saturday deliveries will save it a badly needed $2 billion a year. Looking back through our archive, we found that deficits have been a chronic problem with the Postal Service—at least for the 20th century. Somehow, the postage rates never seemed high enough to cover operating costs, which is why the price of stamps rose steadily from 2 cents an ounce to 46 cents—half of that increase occurring just since 1985.

As far back as 1910, President Taft announced the post office department faced a deficit of $17.5 million ($4.4 billion in 2013 dollar.) This shortfall, according to a 1910 Post article, was caused by two big money-losers. The first was rural free delivery: the department began delivering mail to rural households in 1896, which enabled it to close post offices. But after 14 years, the service was still operating at a loss.

The second source of loss was second-class mail: magazines and newspapers. Even in 1899, periodicals were causing the mail to operate in the red.

In an 1899 article, the Postmaster General, Charles Emory Smith, told Post readers about “The Greatest Post Office In The World.” He proudly listed all the innovative services his department provided, including postal money orders, registered letters, and special delivery. He was particularly proud of the mail cars on the railroads, which were “really working post offices, rushing along at lightning speed, whizzing through towns, swirling around curves, and rumbling over bridges.” Inside the cars, postal clerks “with prodigious memories of lives, offices, stations, routes and timetables” sorted and packaged an average of 1.5 million pieces a mail each year.

But for all its efficiencies and dedication, said Smith, the post office lost $11 million in 1896 because it didn’t charge enough for second-class mail. His department could be profitable if it didn’t have to include magazines and newspapers. But Smith justified the losses because periodicals were then considered “educational.”

The real problem, he added, was the immense size of the country. “Uncle Sam carries letters for 2 cents over an area larger than all Europe. … Considering the immensity of the amount of mail carried, the magnificence of the distances, and the comparative smallness of the force, the showing of the Postal Service of America is marvelous.”

Today’s Postal Service, for all its modernization, still has a lot of territory to cover. No software on earth can shorten the distance a letter or magazine must travel between New York City and Los Angeles. The current price of a stamp—46 cents—is still cheap when you consider it will get your document to its destination anywhere within a space of 3.8 million square miles.