Nixon’s Resignation and the Legacy of a Flawed President

Just before lunchtime on August 9, 1974, the day after his resignation, President Richard Nixon and his family boarded a helicopter on the White House lawn. Stopping at the helicopter’s door, the president suddenly turned and flung out his hands in a gesture that might have indicated either “peace” or “victory.” Minutes later, the Nixons were borne away to a life after the White House.

For his remaining 20 years, Richard Nixon must have fretted over how history would regard him. At least his reputation wouldn’t be tainted by the stigma of impeachment. Just one week before resigning, the House Judiciary Committee had drawn up articles of impeachment that charged him with obstruction of justice, abuse of presidential powers, and hindrance of the impeachment process.

Nixon was spared that indignity when his successor, President Gerald Ford, pardoned him in September.

The pardon wasn’t a favor to a fellow Republican, Ford explained. Rather, he was thinking about the nation. By blocking any criminal prosecution of Nixon, he hoped to stop the social and political rifts that had developed in America during the Senate’s investigation into the Watergate scandal.

Nixon claimed he had acted on selfless motives. In his resignation speech, he declared, “I have never been a quitter. To leave office before my term is completed is abhorrent to every instinct in my body. But as president, I must put the interest of America first. … Therefore, I shall resign the presidency effective at noon tomorrow.”

Putting “America first” might have been a ruse for protecting his dignity, but Nixon’s character was more complex than that. Although his White House recordings revealed he could be petty, prejudiced, and vengeful on a personal level, his policies and actions showed an astute grasp of the national welfare. If he was prone to stumbling on some matters, like authorizing and covering up the theft of data from the Democratic headquarters, he seems to have been far-sighted on the big picture, as Peter Bloch observes in “Richard Nixon — A Great President!” from the November 2012 issue of the Post.

The article shows how much Nixon’s policies changed the U.S. government. Nixon was responsible for many far-reaching initiatives, such as starting a dialogue with China, establishing the EPA, and enforcing desegregation. Nixon was considered a hard conservative in his day — as demonstrated in his virulent anticommunist campaigns — but would be labeled a moderate by today’s standards..

In time, Americans may acknowledge Nixon’s mark on history aside from his crimes. But for the foreseeable future, his popular legacy will be limited to Watergate and his resignation.

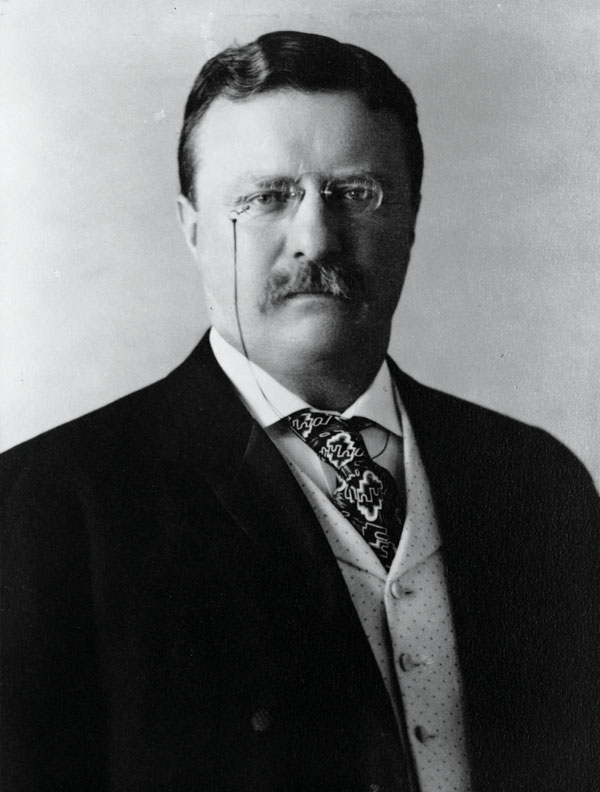

Featured image: Illustration of Richard Nixon by Norman Rockwell for The Saturday Evening Post

E Pluribus Trivia

Nine of our 47 vice presidents inherited the presidency—eight from a president’s death and one because President Richard Nixon quit. Seven vice presidents died in office. Two vice presidents resigned: John C. Calhoun to go to the Senate, and Spiro Agnew to go into hiding.

George Clinton was the first of seven vice presidents to die in office (1812). The second was Elbridge Gerry (1814), who gave his name to the notorious and ongoing practice of gerrymandering—creating misshapen voting districts to ensure your party’s victory. Both served under James Madison, president from 1809 to 1817.

Richard Mentor Johnson, V.P. under Martin Van Buren (1837–1841), rose to political prominence partly on his reputation for having personally killed Shawnee Chief Tecumseh in the war of 1812. His reputation came undone in subsequent years when word got out that his common-law wife, with whom he had two daughters, was the light-skinned slave Julia Chinn. She died in the cholera epidemic of 1833, and her existence was conveniently swept under the rug during his period serving as V.P. For the record, Johnson educated and deeded property to his two daughters.

Theodore Roosevelt found the job of presiding over the Senate so tedious that he often slept at his desk. He famously said of his senatorial charges, “When they call the roll in the Senate, the Senators do not know whether to answer ‘Present’ or ‘Guilty.'”

Charles G. Dawes is the sole vice president to write a hit song. His 1912 “Melody in A Major” later had words added and became “It’s All in the Game.” Tommy Edwards took the song to number one in 1958, seven years after Dawes’s death.

Not until Alben Barkley in 1949 was the vice president called “The Veep,” a term coined by a young Barkley relative. It was noted by the Oxford English Dictionary in 1949 and has passed into common usage.