Most Popular Articles of 2016

As 2016 draws to a close, we wanted to share our most popular articles published this year.

1. The Worst Presidential Election in U.S. History

Read the Post’s response to the presidential election of 1876, which was ultimately decided in a secret, closed session among members of both parties just days before the inauguration.

2. People and Places: Garrison Keillor

Jeanne Wolf interviews Garrison Keillor on stepping down from A Prairie Home Companion and what comes next.

3. Truman and Trump: Explaining the Unexpected Winner

Donald Trump’s victory in the 2016 presidential election bears similarities to Harry S. Truman’s election in 1948, not only in the unexpected outcome but also in the analysis of how and why it happened.

4. Rachel Allen’s Irish Apple Cake

This delicious cake makes a wonderful alternative to more traditional holiday desserts, but it’s a treat any time of year.

5. The Funny Papers

Newspapers may be in trouble, but the comic strip is alive and well — and flourishing online.

6. The New Marilyn Monroe

In 1956, Post editor Pete Martin wrote a surprisingly candid report on the Hollywood icon. He reveals things about the phenomenal blonde that even Marilyn herself didn’t know.

7. Crude Language on the Campaign Trail

Think this year’s presidential campaign has been crass, coarse, and contentious? Campaigns in America have often been rough, with name-calling taking precedence over, and frequently obscuring, the issues of the day.

8. The Drug Epidemic That Is Killing Our Children

Parents who’ve lost children to opioid addiction are taking action, channeling their grief into getting the word out.

9. What Do Birds Do For Us?

Birds are pretty, sure, but increasing scientific evidence reveals that life would be pretty tough without them.

10. When The Chicago Cubs Fought Gods, Goats, and the Front Office

The Cubs waited 108 years between World Series wins. Was it because of a disinterested owner, an angry goat, or bad World Series karma? The article, “The Decline and Fall of the Cubs,” from the September 11, 1943 issue, raises similar questions.

The Worst Presidential Election in U.S. History

Allegations of election fraud and corruption traditionally come after the votes are cast, but in the current election, accusations that the 2016 election is “rigged” started months before election day. It’s unlikely that a presidential election could be “fixed” by one party without the other party learning of it or being implicit in it. In fact, in the closest historical example we have of a rigged presidential election, both parties were part of the deal.

On election night, November 7, 1876, presidential candidates Rutherford B. Hayes (Republican) and Samuel Tilden (Democrat) went to bed believing Tilden had won. He had 184 electoral votes to Hayes’ 165 and needed just one more vote to win. That last vote could have come from any of four states that hadn’t yet reported results: Oregon, Florida, South Carolina, and Louisiana. Each party declared its candidate the winner in all four states.

With the election undecided, the Post editors published “Three Cheers For —.” It put the best face on the situation, urged patience, assured readers that both candidates were honorable and worthy of the office, and showed support for the new president, whoever he was.

Three Cheers For —

Editorial

Originally published on November 18, 1876

At the date of this writing, November 10th, when this page must be sent to press, it is known that somebody is elected President of the United States, but whether Tilden or Hayes is not fully decided, although appearances favor the former.

The fact that the election has been such a close one we believe to be a most happy one for the country. Neither party can afford to conduct the administration loosely or corruptly when its hold on power is so slight; so that in either case we may expect the incumbent to “put the best foot forward.”

The closeness of the result will also, or ought to, be a consolation to the defeated, although many will be disposed to consider it an aggravation. Let it be remembered, however, that we are all in the same boat, whoever holds the helm. The party in power cannot afford to peril the interest of the country, for their own interest are thereby placed in jeopardy. Let the defeated comfort themselves with the thought, “we can stand it if you can.” If taxes are increased, the party who increase them must pay their share, and so of other results which partisans are apt to fear.

The country may congratulate itself on the fact that either of the candidates, personally, is not only unobjectionable, but of a character that will well sustain the dignity of the Presidential office and the honor of the nation. So, then, now we lift our hats and say: three cheers for ———.

Republicans believed Democrats in the South had used force and intimidation to keep black Republican voters away from the polls and had padded the vote tallies with the Democratic ballots of nonexistent men. They created an election board that threw out enough presumably fraudulent ballots to award Hayes the electoral votes.

The Democrats created their own election board, which not only concluded that Tilden had won the presidency, but that a number of Democratic candidates who’d been defeated by Republicans, many of whom were black, had actually won.

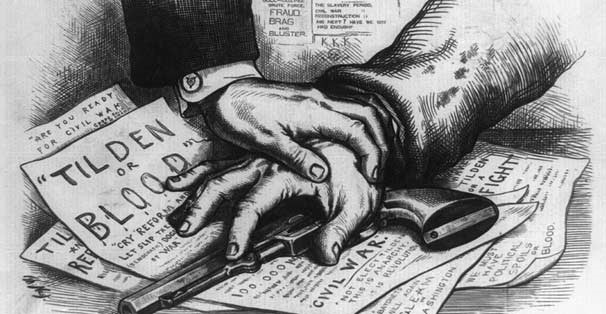

As the stalemate continued, partisan bitterness grew, as did fear that a lengthy political battle would spark another revolt in the South. The editor of a Washington paper was arrested for encouraging Democrats to arm themselves and declaring that he was for “Tilden or blood.” President Grant quietly arranged federal troops around the entrances to Washington to block insurrectionists from entering the city. Soldiers were sent to guard the federal arsenals in South Carolina and Louisiana, where officials worried that mobs would break in and seize weapons for an uprising.

A month after the election, there was less good will and humor in the country. Post editors published “Matches in a Powder House,” denouncing the men who exploited the mob’s fears and resentments. Contrasting the U.S. with revolution-torn Mexico, they urged readers to ignore the men who spoke of taking the law into their own hands.

Violence was worse than voter fraud.

Matches in a Powder House

Editorial

Originally published on December 9, 1876

The madman who would recklessly scatter matches in a powder magazine would soon be placed where his freaks would be harmless. There are crazy heads of the press just now more dangerous to community than the lunatic referred to; writers who for sensational purposes are appealing to partisan spirit already raised to the highest pitch by the exciting political contest through which the country has just passed. Pending the decision for which all are anxiously waiting as to who are the successful candidates, threats of violence, bloodshed, and civil war are covertly or openly uttered apparently with the hope of influencing the result, or at least of keeping up an excitement and profiting by it.

Unfortunately, there is too much powder lying around loosely to permit such firebrands to be scattered harmlessly. Disappointed office-seekers, men wrought up by party feeling, gamblers who have large sums staked upon the issue, desperate speculators mindful of fortunes rapidly acquired during the recent war and ready again to peril the nation to fill their pockets, and that large class of thoughtless men who are ready to rush into any tumult, are not slow to catch at such incendiary utterances.

Such words, whether thoughtlessly or maliciously uttered, should be met with the sternest indignation. This is not Mexico. The people of the United States are law-abiding. They know that for every wrong there is legal remedy; that retribution can be speedily meted out to offenders even in the highest places, by peaceful but sure methods. No wrong would be so monstrous as the kindling of civil war, and those who even indirectly lead their followers to its contemplation are guilty of a higher crime than the worst of election frauds.

The arguing continued while December came and went. As the new year dawned, the three southern states had competing governors and legislatures. Congress took action, and the House and Senate each set up a panel to investigate. The Democratic-controlled House committee found evidence of Republican corruption and awarded the election to Tilden. The Republican-controlled Senate committee found corruption by Democrats and decided Hayes had won.

To break the stalemate, the House Judiciary Committee proposed a bipartisan group to study the election results.

Just days before the March 5 inauguration, the bipartisan commission decided that Hayes had won the election, though he had not won the popular vote — but it wasn’t their decision that settled the matter. It was an arrangement worked out between the Republicans and Democrats in an unofficial, closed session: Hayes would gain the presidency without objection from the Democrats. In return, the Republicans would withdraw their support of the Republican officials elected in the three southern states and, more importantly, remove federal troops from the South, thus ending Reconstruction.

This arrangement essentially handed political power in the South back to the men who had supported secession and served the Confederacy, and hindered efforts to protect the civil rights of African Americans.

Voting Back in the Day

We are thick in the middle of a presidential election, which has been a rancorous affair, causing many Americans to long for the olden days when we were governed by clueless English kings. I wonder if it’s too late to apologize to the British, abolish Congress, and ask the queen to take us back?

When I was a kid, elections were a happy event, earning us a day off school if we assisted the candidates by passing out their pencils, pens, matchbooks, and rulers. Naturally, as the date neared, every child in town took a sudden interest in the body politic and its attendant obligations. We would rise early and hurry to the voting sites to eat the doughnuts intended for poll workers who were overweight and should have been grateful for our intervention but seldom were. At noon, we would walk to the Dairy Queen and eat hot dogs cooked by a light bulb and revel in the democracy that was America.

At 6 o’clock, when the polls closed, we would gather in the courthouse on the town square and watch through the evening hours as the county auditor climbed a stepladder every few moments to write the latest votes on a chalkboard hung high upon the wall. The air was thick with cigarette smoke, making me queasy, causing me to associate nausea with politics, a pattern that persists to this day.

Around 10, the results from the outlying polls were called in, the numbers adjusted to allow for chicanery and error, and the victors announced. They would step to the podium and humbly thank, in order, God, their family, the long-deceased founders of our town, then end with an unrehearsed and lengthy speech on the general wonders of America and the specific virtues of Danville and Hendricks County, Indiana.

My father, the town board president, had raised the speeches to an art form. In my mind it was the acme of representative democracy, watching the votes accrue beside my father’s name on the board overhead, then listening to him extoll the town that had opened its arms to our family in 1957. With the presidency came the responsibility of keeping the groundhog population at bay, lest they destroy the backyard gardens that everyone had in those days. My father was a crack-shot, like Atticus Finch in To Kill a Mockingbird, and the terror of groundhogs everywhere. Most townspeople thought any man unable to exterminate rodents was unfit for public office. To this day, I still half expect presidential candidates to tell us their stance on groundhogs.

Being Indiana, everyone in our town was Republican, except for Bob Pearcy who owned The Danville Gazette newspaper. He also had a maple tree in his front yard that had been twisted a quarter-turn by the 1948 tornado. Pug Weesner, the owner of The Republican newspaper, lost his house in the same tornado, causing some in our town to believe God was a Democrat, temporarily swelling the ranks of that party and ushering Harry S. Truman into the White House.

There was a luster to government service in those days—a regard not only for the office, but also for those who held it. World War II was still fresh in our collective memory, a cataclysmic event resolved by government’s know-how and young men’s courage. If today the less capable are attracted to office, and there does seem to be a weakening in the strain, that was not the case then. The words, “I work for the government” were a statement of pride. One did not run for Congress for the lifetime healthcare; one ran to serve, to help, to make America the “shining city on the hill.” Service to the country was a calling, not a last resort when employment in the private sector didn’t pan out.

Election night, that holy night, was the one school night my parents let me stay up late. By 9 o’clock I would be flagging, so would curl up behind the pillar next to the marble staircase and fall asleep in that cradle of democracy. At 10 o’clock, the last precinct would phone in, and the cheering would waken me.

I would listen to the victory speeches, as one would a bedtime story, lulled to sleep by the soft cadence of freedom.