North Country Girl: Chapter 36 — Pracna on Main

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir.

I started my junior year at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis broker than ever and carrying a ridiculous load of demanding classes, classes that had not yet been paid for, as I was informed by the bursar’s office the first day of school.

I picked up our apartment’s newly installed phone and dialed my dad, resentful that I was going to have to pay for the long distance call.

“Hi Dad. Um, you know, the college hasn’t gotten my fall tuition yet.”

“Yeah, okay. I’ll guess I’ll send a check. But you need to change your major to nursing. That’s the only thing that makes sense. You’ll meet doctors.”

“Dad, I’m not going to college so I can marry a doctor.”

“Well, you’ll marry someone.”

My dad believed that the sole purpose any girl had for going to college was to find a husband. Even if I were unlucky enough to marry someone not in the medical profession, I could put a nursing degree to use tending my own kids through bouts of the stomach flu, pinworm infestations, and earaches.

I hung up, slightly sick to my stomach at this image he had put in my mind, of myself in curlers and an apron, applying a Bugs Bunny Band-Aid to a small disembodied knee.

Every hippie cell of my body revolted at a future as a housewife. I was going to travel to exotic places, have adventures, meet interesting men, and have someone pay me to do it. I could be an airline stewardess, basically a flying waitress, or I could be Margaret Mead and study fascinating sexual mores in tropical climes. I was not about to change my major from Anthropology to Nursing.

Every day after classes I checked the mailbox, which remained empty, except for letters from the University informing me that my fall tuition, $222, had not yet been paid.

I called Colorado, placing a person-to-person collect call to my mother’s dog, who I knew would not accept the call. A few seconds later, my mother called back.

“If I could help you I would. Your father is months behind on alimony. I’ll put a twenty in the mail.”

I went to talk to the bursar, a nice man who was sympathetic but could not really do anything for me. My teary eyes and pathetic sniffling won me a slight extension, but if tuition in full was not forthcoming, I would soon be an ex-coed.

Math was never my best subject, but a quick calculation showed that if I went back to the denim hell of Lancers, at $2.50 an hour, even if I gave up my sanity-preserving White Russian nightcaps and lived on carrot sticks, I would still have to work sixty hours a week to pay for tuition, rent, and books. Which would have been impossible anyway, as the store closed at seven and all day Sunday, not to mention leaving no time for class.

The Minnesota state legislature saved me. Ever since Wisconsin lowered its drinking age, hundreds of Minnesotan nineteen- and twenty-year-olds had smashed up their cars driving home drunk from the state line bars in Hudson and Superior and La Crosse. My on-and-off boyfriend Steve had driven me over to Wisconsin once; I decided that the pleasure of legally drinking in a bar did not make up for the hour of white-knuckled terror spent in a convoy of cars that swerved back and forth across the yellow lines, driven by cross-eyed drunk kids at two in the morning.

Between the desire to keep a generation of kids from killing themselves driving drunk across the state line and the appeal of the extra tax revenue, Minnesota saw the light and passed a law that nineteen year-olds could buy alcohol. And they could also serve it, which meant that instead of folding jeans or dishing out dormitory casserole I could work in a real restaurant, one that served cocktails before, with, and after dinner, and where tips would be folding money, not shiny quarters.

I applied for a waitress job at Henrici’s Steak House, famous for huge hunks of meat, oversized martinis, and according to my friend Sarah who worked there, big tipper businessmen. I was hired immediately and fired almost as quickly. It was a struggle to be my usual perky, overly friendly waitress self because I was so miserably uncomfortable in my Henrici uniform. I looked like a cross between a Playboy Bunny and a French maid from a Pink Panther movie. Starchy, scratchy white crinolines propped up my butt-length black satin skirt, and there was a wide gap between my lace-trimmed strapless top and my actual chest.

I blame that uniform for the fact that my steel trap of a mind could not memorize the mandatory script parroted by Henrici’s waitresses. I knew the dynasties of Egypt, the periodic table of the elements, and every state capitol, but I could not remember to greet people with “Welcome to Henrici’s Steak House, home of the twenty-four ounce filet!” While waiting on my first and last table of customers, I blanked out the entire script, pouring glasses of water, handing out menus, and taking drink orders as silently as Marcel Marceau while the manager glared at me. I finally recalled a single line, shouting out “Here is your piping hot loaf of freshly baked Henrici’s sourdough bread!” to my astonished customers. When I bent over to deliver the steaming loaf a big wad of Kleenex fell out of the top of my dress into the butter. The manager, steaming like a loaf of sourdough, ordered me to turn in my uniform and never come back. The time I had spent training was not on the clock and so I earned exactly nothing for three days’ work.

Waiting for me at home after this debacle was a final warning letter from the bursar, and of course, no check from my dad. I was flat broke. I should have stolen a loaf of bread from Henrici’s, like Jean Valjean.

I wept to my roommate Liz that I had no money and now no job. Liz, like the Minnesota state legislature, saved me.

“Listen, I just heard about a new restaurant opening. They’re looking for waitresses and it’s really close to campus.”

I dried my tears, reapplied my lipstick, hopped on my bike, and rode down to Pracna on Main.

As long as I could remember, when you went out to dinner in Minnesota you went to a “nice” restaurant, with white table clothes, a cut glass dish of celery and carrot sticks and olives set before you, a place where dinner came with a cup of soup du jour or tomato juice as a starter, and hash browns or French fries or baked potato as a side—a place like Henrici’s. Pracna on Main was unlike any other restaurant I had been to. You didn’t go to Pracna to eat a steak, you went there to have fun.

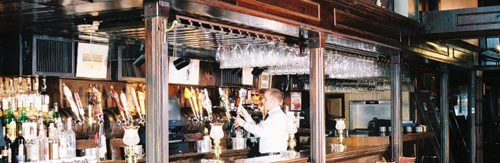

Pracna was an old speakeasy in the warehouse area near the Mississippi River that had been shuttered for years. The original bar had survived, a splendid carved oak specimen fully twenty feet long that was constantly filled with happy drinkers, who started with Bloody Marys and beer backs at eleven in the morning, and partied on until one a.m., when the bartenders told them, “You don’t have to go home, but you can’t stay here.” (Closing was midnight on Sundays; I guess people were tuckered out from church-going.)

Click to Enlarge

There were a handful of tables on an outdoor patio, where people pushed and shoved and acted in a definitely not Minnesota nice way to grab during the few months a year you could drink outside without a parka. Inside, the cocktail area filled up at five with hundreds of people waiting for a table: college students with money, sharp-eyed singles, couples on first dates, lovers who would wait even longer to score one of the two booths with curtains you could close and canoodle behind, young marrieds trying to recapture some fun in their lives. People waited for hours to eat, throwing back gin and tonics and seven and sevens and Harvey Wallbangers, while a vintage juke box blasted rock and roll at a level never heard before in a Minneapolis restaurant. Decades later, every time I hear “Crocodile Rock” I paste a cheery, welcoming, fun smile on my face and reach for my long-gone order pad.

No one went to Pracna for the food. There was a steak, a cheeseburger, chili, and maybe three other entrees, amusingly served on paper plates and bowls that were just sturdy enough to not collapse if you got them to the table quickly. There was an enticing selection of after dinner drinks—grasshoppers, pink ladies, golden cadillacs—but just one dessert: maple nut ice cream with caramel sauce and Beer Nuts, topped with whipped cream and a cherry, and which thankfully did not come in a paper bowl, but in a real sundae glass.

And in an era when grocery stores shut their doors at seven, Pracna served food till eleven o’clock at night. This was exhausting for the waitresses, but brilliant: the folks who were really drunk sobered up a bit over a bowl of chili and then, in true Minnesota style, went back to drinking.

The casually dressed wait staff, mostly cheerful U of M girls and a few cute guys, glowed with youth and good looks. There were a handful of older but still pretty veteran waitresses from fancier joints who were all gob-smacked that they were making so much money serving cheeseburgers on paper plates.

I showed up, filled out an application, was hired on the spot, and headed off to Donaldson’s department store to purchase my uniform: a couple of button down brown-checked gingham shirts to be worn with blue jeans. The gravel-voiced, craggy, alky manager who hired me said, “Make sure to wear your tightest jeans and most comfortable shoes.”

I signed up to work every possible shift at Pracna. In two weeks I had paid my past-due tuition, next month’s rent, and had $600 in one dollar bills stashed in a shoebox under my bed. And I had fun new friends, the other Pracna waitresses. At the one o’clock closing, after we had gently guided the last drunk customers out the door, gleefully counted up our tips, and paid off the bartenders and busboys, they always invited me along to a spot that was illegally serving drinks.

An after-hours bar sounded exotically illicit, a place to meet really, really bad boys. I was dying to go to one of these dens of iniquity, especially under the wings of my new friends. After spending the night perfectly remembering everyone’s cocktail order and making sure they always had a fresh one in front of them, rushing bowls of hot chili to tables before they started to leak all over my hands, and making those stupid sundaes, there was nothing I wanted more than to park my ass on a barstool and have someone bring me a drink.

But I always shook my head, thanked them, and headed off on my bike down the quiet autumn streets to my apartment, where I made myself a White Russian and tried to read at least one chapter of a text book before grasping a few hours of sleep, sleep that was interrupted by nightmares of being tossed out of college for not paying my tuition or of being surrounded by crying toddlers with bloody knees.

I knew a slippery slope when I saw one, and I knew that I was exactly the kind of person who would roll down that slope at warp speed. One late night out would be so much fun that soon it would be three or four, and then there would be missed morning classes and crappy, half-assed lab reports and essays, and no chance of getting the grades that would lead to graduate school and eventually to a career quizzing Maori teens about their sex lives, digging around in the dirt for artifacts, and hanging out with Kalahari bushmen. I was grateful for my job at Pracna, but if I did not want to spend my life with aching feet and hands that smelled like ketchup, I had to keep my pert nose clean and to the grindstone.

My life dwindled down to work and college. The letters from the bursar had frightened the bejesus out of me and the lack of response from my father made me realize that at nineteen, I was on my own. I comforted myself by peering into my overflowing shoebox and stroking my Kansas City roll: here was next month’s rent, next semester’s tuition. If I worked hard enough I would never again need to cry and beg on the phone with my father (not that it had done any good), or have to guilt-trip my mom into putting a twenty-dollar bill in the mail.

Every minute I wasn’t at work or in class I spent studying. As much as I liked them, I didn’t want to end up one of the thirty-year-old career waitresses, who already had faces as hard as their shellacked beehives, who smoked Virginia Slims in the changing room as they bemusedly counted up their tips.

So I said no to my hard-partying co-workers, no to Liz when she invited me to frat keggers, no even to invitations for a night of debauchery from Steve, who was still dealing drugs out of his dorm room. I couldn’t go out. I had translations due in French poetry the next morning. I had to find someone to help me make sense of my scribbled notes from organic chemistry that I may have being trying to read upside down. I had chapters in astronomy to read before I could peer through the University’s Tate telescope and get lost in the stars. I sighed in wonder at the canals of Mars, the rings of Saturn, the Horsehead Nebula, all looking exactly like the lurid illustrations from old sci-fi paperbacks, and pondered if I should change my major to the next one in the alphabet.

And best and worst, at eight o’clock in the morning, three days a week, I had to look as if I actually knew what was going on at a graduate seminar on pre-Columbian culture in North America that I had talked my way into. Professor Pearson, eminent in her field and impeccable in her tailored suits, elegant silver topknot, and pink polished fingernails, looked as if she spent her life playing bridge, not digging about in an ancient midden. I had a girl crush on her, and in class had to guard against falling into a daydream of the two of us on a windswept Arizona plateau, fooling around with trowels and dusting off pottery shards.

Unfortunately, the seminar did not just consist of me and nine MA candidates sitting around a table jawing about digging sticks and the earliest possible crossing of the Bering Strait; that was the fun part. Halfway through the semester Professor Pearson made us learn flint knapping. I was as successful at flint knapping as I was sewing invisible hems back in seventh grade home ec. Professor Pearson would cast her chilly blue eyes over my clumsy stone arrowheads and spear points, ignoring the deep and bloody cuts on my hands from flying flakes of rock, point out invisible-to-me flaws with a pink-tipped finger, and hand me another stone core to work on. Flint knapping killed our imaginary romance.

It was hard enough juggling drinks and overloaded paper plates with hands that looked as if they had been in a fight with a cat over a chainsaw; I cursed Professor Pearson through gritted teeth every time I had to dig down into the always half-empty vat of maple nut ice cream to make Pracna’s one and only dessert, trying not to scrape my hand on the crystal-sharded sides and carefully checking the scoops to make sure they were not streaked with blood. God, I hated those sundaes and did everything I could to discourage people from ordering them, even though they added another $1.49 to the tab. To this day, I cannot bear the sight of a can of Beer Nuts.