Bill W’s Last Drink

On December 11, 1934, William Griffith Wilson took his last drink of alcohol. He didn’t know it at the moment, nor did he know he was about to start a new chapter in his life, and the lives of thousands of Americans.

In the aftermath of his last bout of drinking, Wilson once again entered a detoxification program. He was hoping this time he could end the 13-year struggle with alcohol that had destroyed his career and his health.

He soon realized that simply “drying out” in a sanitarium wouldn’t help. But it was during this hospitalization that he got the inspiration for a better program. Between 1935 and ’36, he worked with a physician (and fellow alcoholic) to create a new approach to ending their addiction to drink. Together they created a program called Alcoholics Anonymous, which Wilson described in a book that he wrote under the pseudonym of “Bill W.”

Six years passed. Two thousand Americans had joined the program and many had recovered sobriety and sanity in their lives. But the program was still relatively unknown, and had never promoted itself to the public. Then, in March, the Post published “Alcoholics Anonymous” by Jack Alexander and introduced this unusual program to the rest of America.

A.A. was unusual for several reasons, as Alexander pointed out. First, it threw out the traditional thinking about alcoholism, which regarded it as a moral failing, a mental weakness, or a personal choice. Rather it defined the condition as a disease, which could never be cured but could be successfully managed. The program’s members told Alexander—

There is…no such thing as an ex-alcoholic. If one is an alcoholic—that is, a person who is unable to drink normally—one remains an alcoholic until he dies, just as a diabetic remains a diabetic. The best he can hope for is to become an arrested case.

Another unusual aspect was the program’s emphasis on personal responsibility and spirituality. A.A. required the alcoholic to be fully committed and willing to seek guidance and strength from some “higher power.”

The program will not work…with those who only “want to want to quit,” or who want to quit because they are afraid of losing their families or their jobs. The effective desire, they state, must be based upon enlightened self-interest; the applicant must want to get away from liquor to head off incarceration or premature death. He must be fed up with the stark social loneliness which engulfs the uncontrolled drinker and he must want to put some order into his bungled life.

If he applies to Alcoholics Anonymous, he is first brought around to admit that alcohol has him whipped and that his life has become unmanageable. Having achieved this state of intellectual humility, he is given a dose of religion in its broadest sense. He is asked to believe in a Power that is greater than himself, or at least to keep an open mind on that subject while he goes on with the rest of the program.

Another unique feature was the absence of ministers, doctors, or other professionals. The program was run by alcoholics, who knew all the dodges, excuses, and denials that applicants would bring to the program.

There is no specious excuse for drinking which the trouble shooters of Alcoholics Anonymous have not heard or used themselves. When one of their prospects hands them a rationalization for getting soused, they match it with half a dozen out of their own experiences.

But of all the remarkable aspects of the program, the most important was its success. Over the years, thousands of Americans were able to reclaim their lives, their families, and their careers through the program.

In 1950, when Alexander wrote a follow-up article, the program had grown to 3,000 groups with 90,000 members.

Ninety thousand persons, roaring drunk or roaring sober, are but a drop in the human puddle, and they represent only a generous dip out of the human alcoholic puddle. [Yet] to anyone who has ever been a drunk or who has had to endure the alcoholic cruelties of a drunk —and that would embrace a large portion of the human family — 90,000 alcoholics reconverted into working citizens represent a massive dose of pure gain. In human terms, the achievements of Alcoholics Anonymous stand out as one of the few encouraging developments of a rather grim and destructive half century.

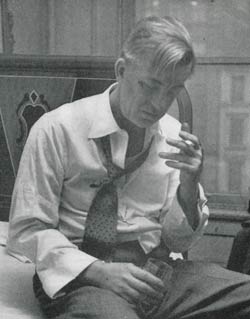

(The top photo, from the Alexander’s 1941 article, illustrated how some member of A.A. managed to continue drinking when their hands were shaking violently: “[They tied] an end of a towel about a glass, looping the towel around the back of the neck and drawing the free end with the other hand, pulley fashion, to advance the glass to the mouth.”)

Here are the pages of the Post article as they appeared in 1941: