Our First Steps to the Stars

Humans could be landing on Mars as early as 2030 according to NASA administrator Charles Bolden. Which means that Americans who saw man first step on the moon may be alive to see a repeat event some 225 million miles away on the red planet.

When space exploration was still new, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration had to convince the nation that it would benefit from space exploration. In the 1959 Post article “Our Plans for Outer Space,” NASA’s first administrator argued for the fledgling space program and laid out plans for the first manned-spacecraft.

Our Plans for Outer Space

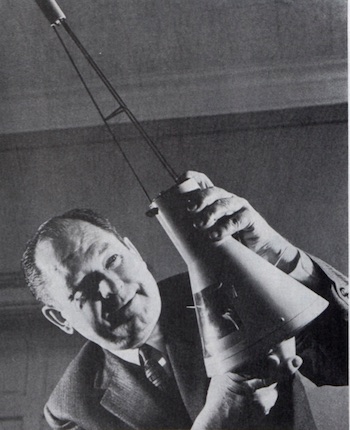

By T. Keith Glennan, NASA Administrator, as told to Robert Cahn

Excerpt from article originally published on February 2, 1959

Some people have asked, why all this urgency about a space program? There are several good reasons. The simplest is man’s basic curiosity. Throughout history he has attempted to get away from being earth-bound. He finally made it on a limited scale with the airplane. Now, for the first time, the advancements of science and technology have made it possible for him to take his first faltering steps toward the stars. …

Every week we get hundreds of letters with inquiries about manned space flight. Just the other day three boys in Oklahoma wrote, “… We would like to be on your first manned rocket to the moon, on the condition that you don’t send it in the next ten years. After that it will be O.K. because we will have finished college.”

While we can’t give encouragement to these Oklahoma youngsters, it is a fact that our present budget contains a project for a manned earth satellite. We call this effort Project Mercury, and the objective is to send a man into orbit around the earth and return him safely. …

No date has been set for this first manned-satellite operation. … We must establish adequate tracking and communications systems all over the world to monitor the orbit of our first man in space. We do not want to have him off in space without contact with our ground stations. We must be able to find him quickly if he lands in the jungle or the sea.

We will take no chances on Project Mercury. People may be killed in space exploration — many have lost their lives in aviation-flight testing. But no life will be lost because we tried to do something before we were ready.

In space exploration we are working with systems in which perfection is necessary. It is not like building a new airplane, where a pilot can test it and say, “Well, it doesn’t quite come up to maximum speed and is a little sluggish on the controls, but it is still a darned good air-plane.” For the highly complicated and difficult space missions, we have to expect that some developments will go slowly and some test vehicles will fail. We don’t like delays. But when pushing the state of the art so far and so fast, we have to operate on a flexible timetable to avoid disastrous failures. …

Once we have succeeded with Project Mercury and repeat manned orbital flights enough times to work out all the problems, it will be time to worry about journeys to the moon and the planets in our solar system. From our present viewpoint, manned exploration of the moon is dependent upon a technology not yet achieved. But we do have a long-range research-and-development program looking toward such a possibility.

Several items in our budget are vital to this long-range planning. Midcourse and terminal guidance systems to orient space vehicles is one research project. Developing improved tracking systems and better methods for transmitting and receiving data are others. We are also doing research toward launching into space laboratories themselves, which can be stabilized and used for experimental purposes. We are sponsoring a study of the systems and subsystems necessary for space rendezvous, where vehicles can be sent up to join satellites already in orbit. These space stations could be used for the assembly of large pieces of equipment — possibly nuclear reactors — needed in such really long-distance space travel as going to the far planets. …

The task ahead is not easy. It is going to cost a great deal of money. Our first year’s budget was $301,000,000, and for fiscal 1960 we will need nearly $500,000,000 to carry out our program. We hope and fully expect, however, that the long-range benefits in even the few practical applications we now foresee in weather forecasting and improved communications will far outweigh the costs.

I will not even try to predict when we will land a man on the moon. Nor will I try to predict what great things may be ahead for mankind resulting from our space exploration — although we already have learned enough not to be surprised at any possibility. I learned my lesson about crystal gazing more than thirty years ago when I was a young engineer installing sound-motion-picture equipment in theaters in the West. At that time, I made the bold prediction that there would never be a full-length all-talking motion picture. I don’t intend to repeat that kind of mistake.

Today, the benefits of space exploration and its refinement of satellite technology should be obvious to anyone using the Global Positioning System on their phones. Satellites are also tracking weather; relaying radio, TV, and telephone signals; and providing military surveillance. To see just how far NASA planned ahead, read Glennan’s entire article, “Our Plans for Outer Space.”