Is Public Opinion Polling Accurate? A Look at Gallup, Then and Now

Many people were shocked by the outcome of the 2016 election. Donald Trump’s win was so unexpected that Americans assumed public opinion pollsters had been equally surprised. Surely at least some of the pre-election polls should have predicted a Trump victory. The notion began circulating that the polls had misread the country. In fact, they hadn’t.

Up to the day of the election, the polls gave Hillary Clinton a three percent lead, which is what she achieved in the final count of the popular vote. However, Trump gained enough electoral votes to beat that slim lead. Furthermore, the election results were within most polls’ margin of error.

Yet doubts remain. A recent Hill-HarrisX poll reported that 52 percent of Americans are doubtful of poll results they hear in the news, 29 percent don’t believe most, but trust some, and 19 percent almost never believe in polls’ accuracy. (If you can believe this poll.)

Despite doubts, studies have shown that well designed polls are accurate. In addition, polls serve an important role: they reflect the voice of the people. Lydia Saad, director of U.S. social research at Gallup, says, “The goal of polling is to amplify the voice of the public. If we ever lost this ability to sample America’s opinions, it’d be surprising how lost we’d feel. We wouldn’t know what people are thinking, and we’ve have to rely on unreliable sources.”

Unreliable sources are all that America had for years. Before George Gallup began gathering opinion data in the 1930s, politicians relied on such things as newspaper editorials, letters to the editor, and the frequency of labor strikes to read the mood of the people.

When Gallup began taking surveys, his group conducted door-to-door in-person interviews in select locations chosen to be representative of the whole country.

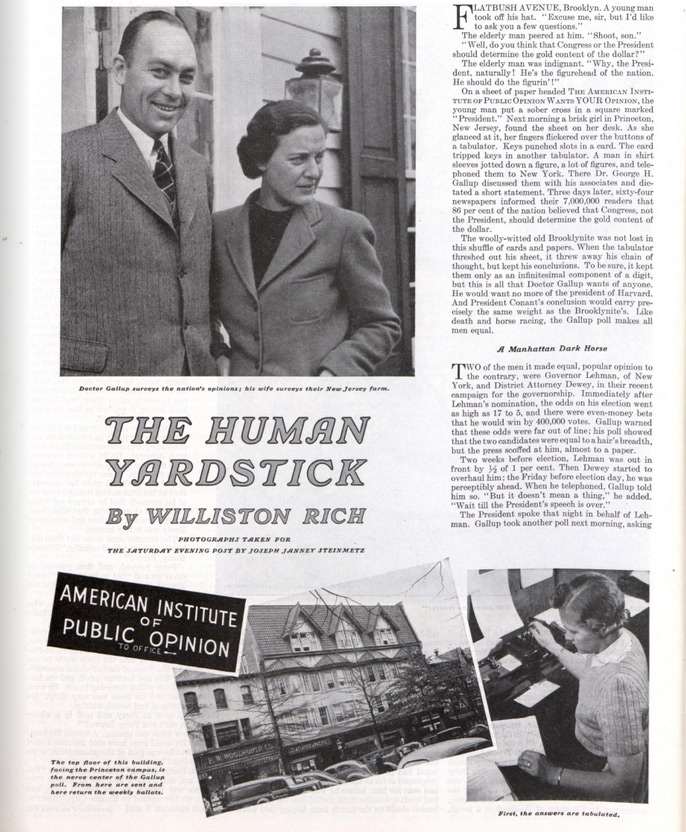

Telephone polling made it much easier to obtain a true random sample of the country. But there were doubters, as the Post reported in 1939 in “The Human Yardstick.” Gallup had predicted that President Roosevelt would certainly be re-elected in 1936. Republican newspaper editors challenged his assertion, making an argument pollsters have often heard over the years. “It can’t be a national poll. I haven’t received a ballot. What’s more, nobody in my neighborhood has!”

And though critics may still say this about polls, the facts are that public opinion polls have only become more accurate over the years. “We use well defined methods based on randomization,” says Saad. “We pick random subjects so that everyone has an equal chance of being in the pool of data.”

Many polling organizations, including Gallup, have increasingly relied on conducting surveys by cell phone. Today, cell phone calls account for 70% of Gallup’s data, and this percentage is still rising.

Polling methods vary somewhat based on the polling organization, but Gallup’s “live” (telephone interview) polling is the most common. The pollsters purchase phone lists generated from blocks of area codes and exchanges known to be assigned to cellphones or household landlines and then randomly generate the last four digits.

“We’ll call, and if we don’t reach anyone, we’ll call back. To get a representative sample, we need to include people who aren’t home very often,” Saad explains.

The raw data is then weighted to get a sample that matches census statistics for five criteria: age, race, region, gender, and education.

One of the more frequently challenged polls Gallup conducts is the presidential opinion poll, which is often accused of being biased. “Our procedure has been standardized since the days of President Truman,” says Saad. “For example, when we reach one of our subjects, we first ask them if they approve or disapprove of the president’s performance. Only then do we ask about other issues like the environment, healthcare and so on, because we find that asking about these issues first can change the subject’s opinion about the president.”

Even though polls aren’t perfect, they are currently the best way to measure public opinion. “If the public decides polls are bad and stops answering them, it will be hurting itself in the long run,” says Saad. The alternative is to rely on commentators or online information. “And there’s no way to gauge the accuracy.”

Featured image: Shutterstock