Considering History: U.S. Imperialism and Puerto Rican Activism

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

Fifty years ago, on July 26, 1969, the Puerto Rican community organization known as the Young Lords opened their New York chapter. Originating out of early 1960s Chicago street gangs, the Lords had been formally constituted in Chicago in September 1968, on the 100th anniversary of the Grito de Lares rebellion against the Spanish in Puerto Rico. But it was with the opening of the New York chapter that the Lords truly came into their own as a national social and political activist movement, as illustrated by that chapter’s July 27 “Garbage Offensive” protests against the city’s substandard garbage collection services in Puerto Rican and other minority neighborhoods.

The 50th anniversary of those events offers us a chance to remember these Civil Rights era communities and campaigns and better understand both Puerto Rico’s relationship to the United States and Puerto Rican political and social activism, in an era when both those topics have become central national conversations once more.

The relationship between the U.S. and Puerto Rico began with the late 1890s events of the Spanish American War. Although the majority of that conflict was fought in the Philippines and Cuba (Teddy Roosevelt’s famous charge up San Juan Hill took place in Cuba, not in Puerto Rico’s capital city of the same name), U.S. forces did invade and occupy the coastal town of Guánica on July 25, 1898. And in the February 1899 Treaty of Paris that formally ended the war, Spain ceded Puerto Rico along with the Philippines and Guam to the United States.

The relationship that followed was a clearly colonial and imperial one throughout the 20th century, with the U.S. ruling the island through both the military and U.S.-appointed governors. The 1900 Foraker Act did create a House of Delegates that would be directly elected by Puerto Rican voters, but the island’s upper chamber (initially an executive council that gradually evolved into a senate) and governor continued to be appointed directly by the United States government. Similarly, the island continued to have no voting representation in Congress, a fact that became particularly significant when through a series of racist “Insular Cases” the Supreme Court and U.S. government deemed Puerto Rico “territory appurtenant and belonging to the United States, but not a part of the United States” as the island was “inhabited by alien races.” This ambiguous and fraught status, “foreign in a domestic sense” as the Court put it, left Puerto Ricans with far fewer Constitutional rights than their mainland counterparts.

Two moments in the 1910s reflect the evolution and ongoing effects of that fraught relationship between Puerto Rico and the United States. In 1914 the House of Delegates voted unanimously in favor of independence from the U.S., but the U.S. Congress rejected the vote as a violation of the Foraker Act. Three years later, Congress passed the 1917 Jones Act, which granted U.S. citizenship to all Puerto Ricans born after April 25, 1898. But the law was opposed by the entire Puerto Rican House of Delegates, which saw it as a cynical strategy to make it possible for the U.S. to draft Puerto Rican young men into World War I military service. While that motive was certainly present and while the law did not change the island’s overall colonial status (indeed, it reinforced U.S. control, another reason the House of Delegates unanimously opposed the law), it nonetheless contributed to evolving possibilities of U.S. citizenship for Puerto Ricans.

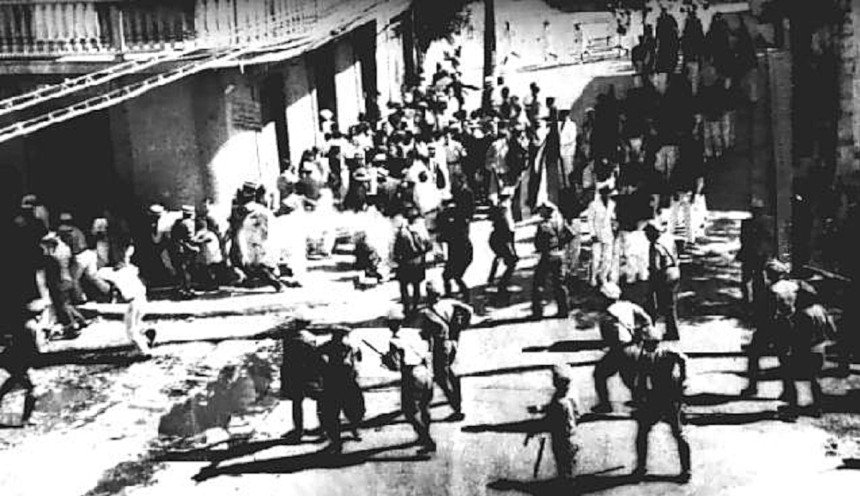

Alongside those legal and governmental histories, the early 20th century likewise witnessed a number of Puerto Rican social and political uprisings. Pedro Albizu Campos, leader of the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party and a principal advocate for Puerto Rican control of its own government and affairs, was particularly instrumental in organizing such efforts, including a 1935 protest at the University of Puerto Rico and a 1937 mass action in the city of Ponce. At the latter protest, Puerto Rican Insular Police opened fire on the protesters, killing 19 and wounding hundreds in what has come to be known as the Ponce massacre. These and other events led to gradual shifts in the U.S.-Puerto Rican relationship, including President Truman’s 1946 appointment of the first Puerto Rican-born governor, Jesús T. Piñero, and a subsequent 1947 amendment of the Jones Act that allowed Puerto Ricans to directly elect their own governors.

Throughout these decades, and even more so in the years after World War II, many Puerto Ricans moved to the mainland U.S., forming sizeable communities in cities like Chicago and New York and bringing with them the legacies of these contentious relationships. 1960s groups like the Young Lords embodied Puerto Rican activist opposition to governmental control and racist oppression. It’s no coincidence that the group’s first 1968 efforts in Chicago were in response to the city government’s evictions of Puerto Rican residents and police brutality against the community as part of Mayor Daley’s urban renewal campaign, trends that the Lords and their Chicago leader Jose Cha Cha Jimenez countered with arguments for Puerto Rican self-determination and community leadership.

With the 1969 founding of the New York chapter, those efforts became truly collective and national, and would continue throughout the next decade. Most famously, New York Young Lords leader Vicente “Panama” Alba was instrumental in both orchestrating and speaking in response to the October 1977 takeover of the Statue of Liberty by 30 Puerto Rican nationalists, a group advocating for both specific actions (such as the release of five political prisoners who had been held by the U.S. government for more than 25 years) and broader ideas of Puerto Rican self-determination and independence. To quote Alba himself, speaking to a documentarian 35 years after the takeover, “the end result was that the picture of the Puerto Rican flag [on the Statue’s forehead], and the issue of Puerto Rico being a slave nation and colony, … became an international issue.”

In 2019, thanks to both the failed federal response to the devastations of 2017’s Hurricane Maria and the ongoing, stunning mass protests against Governor Ricardo Rosselló, Puerto Rico has become a national and international topic once more. These and other unfolding stories need the historical contexts of the Young Lords’ 1960s and 70s activism, and of the dual legacies of U.S.-Puerto Rican relations and Puerto Rican resistance that have led to both their moment and ours.

Featured image: Qzonkos via Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license / Wikimedia Commons

Puerto Rico Celebrates Constitution Day and a New Beginning

It’s no secret that Puerto Rico has had its share of hardships in the past few years. Hurricane Maria left an indelible imprint, followed by a delayed relief response that revealed that many Americans don’t realize that Puerto Rico is part of our country. And last night, after weeks of public outcry and protests following a corruption investigation, governor Ricardo Rosselló announced his pending resignation. That forthcoming transfer of power is especially relevant today as the largest and closest U.S. territory celebrates its Constitution Day.

Puerto Rico isn’t just the largest U.S. territory; it’s bigger than the other 15 combined. Sitting 1,150 miles from the continental U.S., the Island of Enchantment became part of the United States in 1898 under the Treaty of Paris that ended the Spanish-American War. For years, Puerto Rico marked July 25th as Occupation Day, as it was on that day in 1898 that U.S. forces arrived. In 1952, when the new Constitution went into effect, the date underwent the official name change to Puerto Rico Constitution Day.

Puerto Rico’s official status as the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico stems from U.S. Congressional legislation enacted in 1950 to allow the island to hold a constitutional convention and draft their own document. The title of Commonwealth recognizes that Puerto Rico is a dependent territory, but “organized but unincorporated,” meaning that it has the functionality of a state but does not belong to any of the other states in the country.

The overall structure of the Puerto Rican Constitution is similar to the U.S. document, as it contains various Articles of organization and a Bill of Rights. While most of the enumerated rights echo the American original, such as freedom of speech, assembly, press, and religion, there are individual instances where the rights receive more definition. Notably, this includes direct language on discrimination in Section 1 of Article 2. It reads: “The dignity of the human being is inviolable. All men are equal before the law. No discrimination shall be made on account of race, color, sex, birth, social origin or condition, or political or religious ideas. Both the laws and the system of public education shall embody these principles of essential human equality.” One interesting omission is that the document lacks rights guaranteeing a trial by jury.

Education also receives strong support in the fifth section of Article 2. Notably, it establishes that school should be free and secular; it reads in part, “Every person has the right to an education which shall be directed to the full development of the human personality and to the strengthening of respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms. There shall be a system of free and wholly non-sectarian public education. Instruction in the elementary and secondary schools shall be free and shall be compulsory in the elementary schools to the extent permitted by the facilities of the state.”

The annual celebration of the Constitution includes a ceremony in Old San Juan and a reading of the Preamble to the Constitution. It’s been a rough year for the island. Last summer, CBS News covered the turmoil-laded process behind the re-establishment of the island’s damaged power grid. And just last night, the governor resigned after mass protests that came in the wake of investigators finding “five offenses that constituted grounds for impeachment.” His resignation is effective on August 2.

Writer Marco Lopez believes that Rosselló’s resignation represents hope. Lopez, who worked on Puerto Rico Strong: A Comics Anthology Supporting Puerto Rico Disaster Relief and Recovery, which won an Eisner Award (the comics Oscar) at Comic-Con International: San Diego last week, says, “It means a brighter future. A new beginning. A new perspective . . . Puerto Rico and its citizens have shown that they’re in charge of their path in life and the island’s future and know where to take it. That they won’t stand by and let anyone disrespect them.”

The identity of the next governor isn’t the only lingering question about Puerto Rico. Legislation currently making its way through Congress, , H.R. 1965: Puerto Rico Admission Act, would make Puerto Rico a state if successful; 97 percent of voters (23% of the 3.3 million citizens cast ballots) there voted in favor of statehood in a referendum in 2017. Over 120 years after the United States arrived in Puerto Rico, it remains possible that Puerto Rico could finally arrive in the States.

Featured image: Wikimedia Commons