When Christmas Pie — and Christmas Itself — Was Banned

When I was a girl, my parents and I spent Christmas Day with my father’s family. And when we moved to another city, we always drove back for the traditional Christmas.

It was the same each year: Turkey and all the trimmings, polished off — somehow I always still had room — with pumpkin pie. But I had no idea how far back some of the traditions went, including the celebration of Christmas itself. It was only later that I chanced upon the fact that Christmas was not only not celebrated in some places, it was banned. Legally. In this country, in New England, and across the Pond in England.

The years in which Christmas was banned, by law or custom, would leave their mark on Christmas and how we celebrate it. Mince pie — also known as Christmas pie — is one example.

Christmas pie was originally a small British fruit-based mincemeat sweet pie traditionally served during the Christmas season. Its ingredients are thought to go back to the 13th century when returning European crusaders brought back Middle Eastern recipes.

It may go back still further, to the old Roman custom during the Saturnalia of Roman priests in the Vatican being presented with sweetmeats.

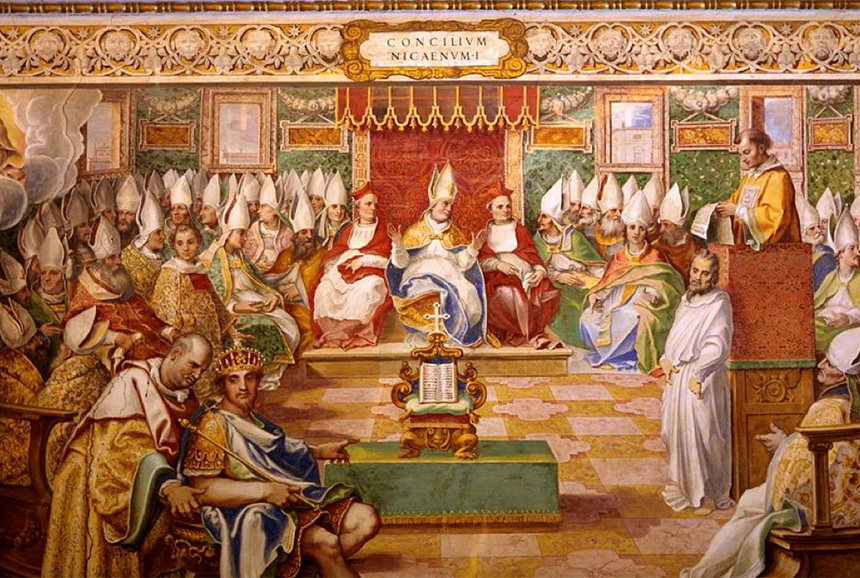

When in 325 A.D. the Council of Nicaea set the date for the birth of Jesus as December 25, that, intentionally or not, grafted the new Christmas onto the old Saturnalia, which was the most popular celebration of Roman times. The seven-day festival that started December 17 to honor the god Saturn and welcome the winter solstice gave us today’s tradition of holiday greenery, gift giving, and the office party (or variations thereon), for the Saturnalia was a time of much drinking, some carousing, certainly unrestrained revelry.

Complaints about Christmas, or more specifically the celebration thereof, threaded through the Dark Ages, the Middle Ages, and then came into their own in Tudor England.

Christmas in Merrie Olde England was seen by the Puritans as a bit too merry. The holiday had come to be marked by bear baiting, beer and ale, and other spirits flowing in the taverns on Christmas Eve, rowdy crowds celebrating “the Lord of mis-rule.” Come Christmas morning, minstrel-like parades would march down the aisles in churches where services were being held.

Unable to rein in the excesses, the Puritans threw the baby out with the bathwater. There would be no Christmas. Not just the celebrations and traditions, but Christmas Day itself. It would be just another day.

Their no-Christmas policy crossed the Atlantic with them on the Mayflower. When the Pilgrims landed at Plymouth in December 1620, they observed the Sabbath on Sunday, but, come Christmas Day, went ashore to work.

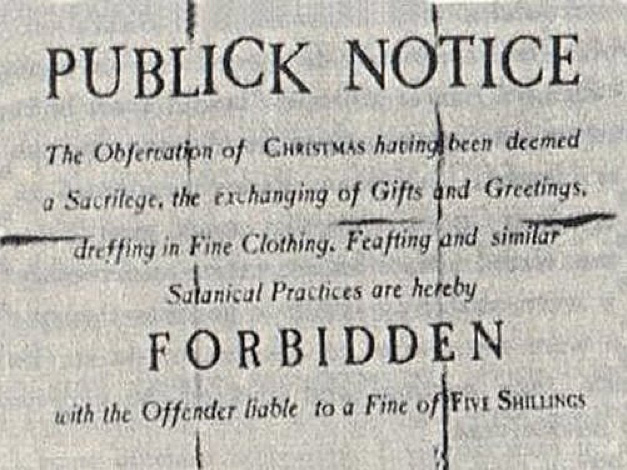

Back in England, when the Puritans came to power under Cromwell, Christmas was banned by an act of Parliament in 1647. On Christmas Eve, the town crier would move through the streets of London, ringing his bell, proclaiming, “No Christmas! No Christmas!”

And no Christmas meant no Christmas pie.

The small fruit-based sweet pie had grown larger with the years, and by the 17th century it was long and narrow, with a depression in the center for a baby doll representing the baby Jesus in his manger. The Puritans considered this idolatry and would have none of it.

When Parliament lifted the ban on Christmas in 1660 — Cromwell was out and Charles II had ascended the throne — Christmas pie returned, in the circular form we know (and with no doll).

My family did not serve mince pie; we had pumpkin pie in Michigan then. When we moved to New England, I still enjoyed pumpkin pie but discovered they not only had mince pie as an alternate but also squash pie.

That pumpkin pie became a national favorite may go back to the Pilgrims, who, being Puritan, did not celebrate Christmas but had a great plethora of pumpkins. So great it inspired the verse:

We have pumpkins at morning, and pumpkins at noon,

If it was not for pumpkins, we should soon be undoon.

Whichever pie you choose for your celebration — pumpkin or mince or sweet potato or squash — may it bring as much joy as your other Christmas traditions.

Featured image: Saturday Evening Post cover from November 18, 1905, by Guernsey Moore ©SEPS