The World Isn’t Finished (and Neither is the Car)

Ellen Pyle

November 24, 1934

This article and other features about the early automobile can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition: Automobiles in America!

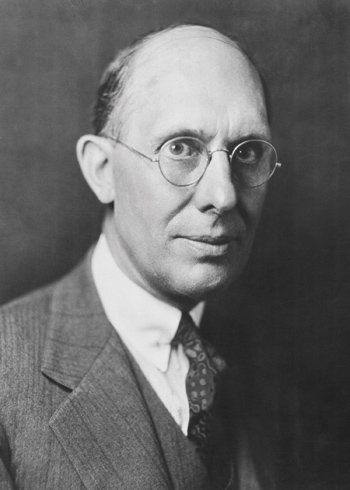

Charles F. Kettering was head of research for General Motors from 1920 to 1947. The holder of 186 patents, he was best known for inventing the electrical starter, leaded gasoline, Freon gas (essential for air conditioning), and a system for using color paints in mass-produced cars. In this article written for the Post during the dark days of the Depression, Kettering invites readers to take the long view, reminding them that life (and the auto business) is constantly changing for the better. It was an important message from a chronic optimist.

A man said to me the other day, “I don’t see what you can do to improve the automobile. It looks like perfection to me.” I said, “I hope it isn’t, because my job is gone if it is.” And that’s a fact. Most of our jobs would be gone if the products of the industries in which we are engaged should be adjudged perfect. Because then it would just be a question of employing enough men to produce the perfect thing. In the reorganization of business on this basis, not more than 30 percent of us would have employment.

In these days, as always, the most important fact from every angle is that the world isn’t finished. This holds in every realm — in business, in matters of unemployment and economic recovery, in the organic world, the psychological, the spiritual, the personal, and all others. Growth is the essence of life, and evolution functions in business as in biology. New standards evolve, and new human needs, new products, new jobs, just the same as new living forms do. Of course my work has been limited largely to the automotive field. But that’s a big world in itself, touching many others and exemplifying many truths. If the world had ever stood still, we might still be in the age of the dinosaurs and pterodactyls. But there aren’t any of these creatures around. The principle of the thing, as Darwin showed, is that the world moves on, that Nature is never satisfied with existing forms, but is always trying for new ones. The world has moved on from the first living cell to the modern man. It is moving on toward higher living forms and better social conditions. It will continue to move on toward a higher standard of living for everybody, toward a greater degree of beauty, strength, and perfection in all things.

The Future Is Bright

We in the automobile business believe that time is no kinder to us than to anybody else. But we think we try to recognize it more. We bring out yearly models on the theory that business and social conditions progress as producers hit a constant rate of improvement. We believe that for the next 10 or 20 years at least we can bring to you an improved and a better automobile. I think I can illustrate the basis for my belief by considering the three basic materials with which we work — rubber, petroleum, and steel.

I always admired the man Dunlop, because I think that anybody that had the nerve to propose a rubber tire to run on the ground when everybody knew that steel was the only thing that would do, must have been a man of distinct nerve and bravery. He planted the idea, and the simple rubber tube that he made progressed through various stages of evolution, until, a half-dozen years or so ago, the industry turned out the balloon tire. The lifespan of a tire went from 3 and 4 thousand miles up to 15 and 20 thousand. We began to experience a new ease in riding and a new safety in driving.

We owe a great debt to the rubber people. Yet I don’t think their job is finished. And they don’t either. In the future, we can expect tremendous improvement, not merely trivial additions, but evolutionary — and I might say, revolutionary — developments in tires.

In regard to petroleum, we have always known it to be a marvelous fuel, but in the past four or five years we have begun to recognize that the possibilities of developing power from the internal combustion engine are just on the verge of development. It is a fact that our best automobiles today deliver under normal driving conditions only about 7 or 8 percent of the total energy in the fuel. There is actually enough energy in one gallon of trade gasoline to propel a small car from Chicago to Detroit, some 300 miles, instead of the 20 miles attained.

In steel, we used to believe that the elastic limit was about 80,000 pounds per square inch, which is to say that if we pulled a square inch of the best steel we used to have with 80,000 pounds’ pressure, it would go back to its original position. The place where steel fails to go back is called its elastic limit. But then we came along with better steels, and the elastic limit went up to 100,000 pounds per square inch, and finally to 125,000 pounds, and today we are using steels under pressures of 300,000 pounds per square inch and they are standing up perfectly. Nobody knows where the limit will finally be found, if indeed it is ever to be found. Ten years from now, we shall be thinking thoughts and dreaming dreams not even in our conscious thought now.

Nourishing an Idea

Ideas always do go on to a harvest. They are like corn — first the seed, then the blade, then the stalk, then the flowering, then the grain in the ear. The parallel holds in many ways. When a man travels, observes, wonders, and questions about things, that is like plowing the land, the seed bed of his mind. Then the seed must be planted. Of course the rains may come and wash out the seed, or the hogs root it up, or the sun bake and dry the kernel. If the shoot does push through, the weeds may choke it, or the high winds rip it out of the ground, or the drought kill it. But if a man keeps on planting corn he will eventually reap a harvest.

I’ve seen this work out so many times. One submits an idea to a committee. If the committee is in an unprogressive industry not used to new ideas, it will probably brush that new idea into the wastebasket; nevertheless, one will have plowed a little ground, made it ready for the planting of the idea. One goes on submitting it, and the committee keeps on pushing it off the table, and pushing it off and pushing it off, until, perhaps, after two or three or four years, somebody says, “Hey, wait a minute. There’s something in that.” Then one may be sure that the seed of the idea has sprouted, that the shoot has pushed through the ground. All one has to do then is to keep the weeds down, work the land and the crop. The seed will yield a harvest of a thousandfold or more.

That is Nature, and one may be sure of the harvest, though if it is a big idea he is planting, much time may be required. The idea of the automobile was simple enough, but it took a long time for it to grow into its present magnitude. The world seldom sees that harvest until it starts to materialize, because it’s a new thing that the world has never heard of and doesn’t believe in. But when people do begin to see the harvest, they rally round and get all enthused and start making the thing a whole lot bigger than it really is. With one voice they all say, “How blind we were not to see this thing in the first place.” They start out to make a hero of the man who promulgated the idea, and build monuments to him after it is too late to do him any good.

The Nature of Work

In business, as in all things, we must swing back to the old position of being guided by Nature. Because life is just that way: That is all. As ideas are like seed corn, so wealth itself is like the harvested ears. One has to work to produce wealth. You can’t wave a wand and take it out of a hat. In order really to prosper, you have to study your land, perhaps fertilize it, then plow it, plant it, scratch the crust, work the crop, keep the weeds down and guard against insects, blight, and marauders. After the sun has warmed and rains watered, there is the labor of harvest. The man who follows this life and knows that it’s his job, is happy in it.

Of course, here’s where the business of living really begins to come in. You know the story of the old mule that used to pull the slag oar out at the ironworks. The company became prosperous, and decided that they ought to have a little steam locomotive to pull the slag car. They turned the mule out to pasture. The first day he seemed to enjoy it; the second day he hung around the gate; when the man came to work on the third day, they found the old mule leaning up against the slag car. Maybe the mule didn’t exactly enjoy pulling the slag car, but it was his job and he was lost without it. Most men, like the mule, like to do what is in them to do. The farmer has to have his hands on the plow handles; the sailor must live around the sea; the painter must paint; the mechanic work with his monkey wrench; the racing driver work to win the Indianapolis races.

What is more, there is a certain natural rhythm in work, as one can see by watching a blacksmith at his anvil, or a sower flinging the seed with a motion nicely tuned to his stride, or several hoe hands working in the field in natural unison of movement. It is only when one gets out of this natural way of life, and gets all excited about the possibility of adding up figures in the monetary realm, that a man runs into trouble.

—“The World Isn’t Finished,”

The Saturday Evening Post, April 23, 1932