North Country Girl: Chapter 53 — Hello Groucho, Good-bye James

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir.

Even though I was working semi-steadily, I didn’t offer James money. It was never a relationship between equals; my piddling and erratic modeling checks for $90 or $225 would not have made a dent in his problems, only blasted out a hole in his pride.

I was stashing my get away money in case the worst happened, whatever that might be. Maybe James would rob a bank, or kill himself, or go back to selling Cadillacs in Des Plaines. When I moved in with James he was fun, generous, exciting. Now I was living with a hollow man and insanely hoping that the old James was not gone for good.

The market fell, and then continued falling. James turned into a zombie, a zombie who was now having trouble scraping up enough money to pay the rent. I came home one day to a pink “Late Payment” notice shoved under the door, which I placed on the coffee table; it went unmentioned and unmoved.

When James had cash in his pocket, it came from his backgammon winnings. The backgammon club was the only place James went at night; there were no more meals in nice restaurants or disco dancing at Faces. The last night I was ever there, I watched James distractedly pat at his pockets while asking his opponent if he would take his IOU. The winning player gently reminded James that the club did not allow IOUs, all bets were to be paid in cash or check. When James began lifting off his heavy gold chain, the man, whose only jewelry were onyx cufflinks, quickly demurred, murmuring, “Just this once.” After that I couldn’t bear to go back, and spent my evenings alone, pretending to be asleep when James got home, not wanting to know if he had won or lost.

At this point the stress unhinged me. I thought, “You know what will make things better, Gay? A dog,” though I had never had a dog in my life. I didn’t bother asking James, I just went to the closest animal shelter. It was filled with the sounds and smells of dogs, dogs who were locked away in row after row of cages, stacked to the ceiling, each dog looking more pitiable than the next. I was torn; they all looked so undesirable, all destined to be put down. A three-legged dog briefly stole my heart, before I saw the Dog Least Likely To Be Adopted: a hairless, toothless Yorkshire terrier with cataracts.

The pound guy told me that the Yorkie had been owned by an elderly woman who had barely been able to take care of herself and seemed to have completely forgotten that she had a pet; the dog, who would have been long in the tooth had they not fallen out from malnutrition, was recovering from a case of mange that left him mostly bald. I gave the pound guy $20 and he gave me the dog, who I named Groucho, along with a collar, leash and some canned dog food suitable for toothless dogs.

I guess Groucho had not been walked much; when I pulled on the leash, he lay down on his side so I had to drag him out of the animal shelter. I drug him a bit down the sidewalk, then realized I couldn’t do this all the way back home, so I picked him up and carried him. He weighed less than a loaf of bread.

James hated Groucho on sight, not that there was much to like. But Groucho may have been my guiding animal spirit sent to get me out of that awful situation. Pound guy had assured me that Groucho was housebroken; he did poop every time I took him out for a drag. But Groucho also pooped the second I left the apartment, varying where he left those little Tootsie Roll turds that James always managed to step in; if James made it safely out of the bedroom, there would be a tiny poop hiding in the white shag of the living room rug.

“This #$@%ing dog has to go,” James said. I agreed. I had to go with it.

My modeling career was puttering along well enough that I could rent a $140 a month studio, get the phone and electric hooked up, and furnish it from Goodwill.

James barely noticed as I packed my clothes and books and Groucho; he was riveted to bottom part of the TV where the stock market ticker slid along with its tale of woe. There was no steamy last kiss, no tears. I pecked his cadaverous, stubbly cheek and said “Goodbye.” “See you around,” said James. But he didn’t. We lived a ten-minute walk apart from each other, yet I never saw him again.

Groucho and I moved into our tiny studio on quiet, leafy Burton Place. Every day when I came home, Groucho would be sitting on my second-hand bed, waiting for me, his tongue lolling out of his toothless jaws. He never pooped in that apartment once.

I was landing enough modeling jobs that I had stopped having nightmares about being locked in a coat check. Almost every other month I had a solid week of work at the Chicago Convention Center, handing out brochures at the Furniture Show, running a towel folding machine at the Hotel and Restaurant Trade Show, and at the Auto Show, luring prospective car buyers in range of voracious car salesmen.

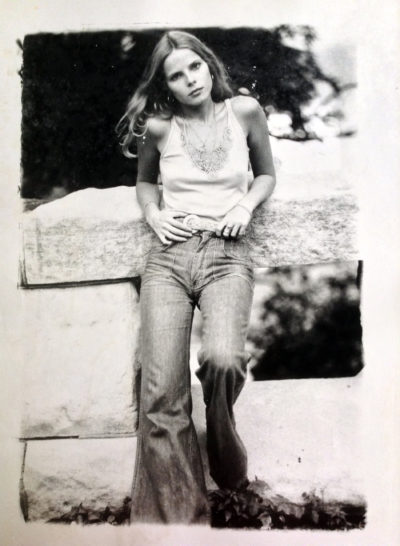

Ford Motor Company loved me; I had that beamy, fresh, All-American look, the look of a girl who belonged in the passenger seat of a Mustang. When they hired me I was sure they would put me in a pretty gown and stand me up on a revolving platform next to their newest model, and all I would have to do is grin and wave.

The man from Ford looked at the bevy of models assembled in the basement of the Convention Center, pointed at me, and said “You. You’re gonna be the magician’s assistant.”

He did not see an innate talent for sleight-of-hand; he saw a girl small enough to disappear inside a magic box.

Every car company at the Auto Show had some kind of come-on. Ford had a fifteen-minute magic show, every hour on the hour that brought families into the exhibit and kept the kids entertained while the salesmen swooped down on the parents. I didn’t even get a cute, sparkly magician’s assistant outfit; I wore a plain jane blue dress with “Ford” stitched in white. I stood next to the magician on the postage-stamp-sized stage and handed him scarves and hoops and held his top hat. For the final trick, I stepped into a black box, which looked like an upright coffin. The magician closed the door on me and intoned a few magic words while I scrunched down as fast as possible into the bottom of the box, pulling three mirrored panels away from the back and sides so they encased me in a tiny triangular space. The magician opened the door for a split second, the mirrors reflected the interior’s matte black paint, and poof! I had vanished. Cue applause. I sprung up, the coffin door opened, and I stepped out to take my own quick bow before I headed back out to the convention floor to pass out “Free Show: The Magic of Ford!” flyers.

The next year Ford had a different gimmick: Models, dressed in those same plain jane blue dresses, buttonholed all the grown-ups who walked into the Ford exhibit and asked “Would you like to win $100?”

“What’s the catch?” every suspicious attendee wanted to know.

“No catch at all! Here’s a raffle ticket. Find someone with the same number and you’ll both win $100!”

For the ten days of the Chicago Auto Show the Ford exhibit was complete pandemonium, as people dashed about comparing raffle tickets. Gangs of kids picked up tickets that had been tossed on the floor or begged grown-ups for theirs, and ran riot, yelling numbers at each other and anyone holding a small piece of paper. It was supposed to be for adults only and then only one raffle ticket per person, but it didn’t matter, you could take a thousand tickets and not win.

The game was as rigged as any carny con, and I was the shill, dressed in civvies almost as homely as those dresses by Ford. It was designed to get foot-dragging buyers on to a car lot to close the deal. When one of the salesmen had a hot prospect for a Family Truckster, he sent someone out to find me. My job was to approach the potential car buyers, ask them to read the number on their raffle ticket and then squeal “Wow! That’s my number too!” I immediately handed my ticket to the salesman; the prospects never realized there wasn’t really a match; they were too excited about winning. But instead of a crisp $100 bill, what the suckers got was a certificate in that amount. The $100 was waiting for them at their local Ford dealership. Before they could complain, I would gush, “Oh thank you so much! I can’t wait to go to Skokie Ford and collect my $100!” Then I dashed off and hid in the crowd until the next set of chumps appeared.

Trade shows kept me in Campbell’s soup, Groucho in kibble, and paid the rent, but were anything but glamorous. I spent eight-hour days standing on a concrete floor, next to adding machines or surgical supplies, trying to ignore my throbbing feet, looking as cute and approachable as possible, which was ninety percent of the job. The other ten percent was passing out samples or pins or pens or brochures, and fending off amorous salesmen and conventioneers, “C’mon honey, it’s just dinner. Put a little meat on those bones!” I turned them down with a nice girl smile, and gently removed their hands squeezing for either meat or bones on my butt.

As much as I missed my brief former life of champagne cocktails and Dover sole, of being a regular in places where your drink arrives immediately and there’s a nice woman to hand you a towel in the ladies’, I had no desire to eat a chopped up steak at Benihana’s with the biggest manufacturer of stainless steel cutlery in America. I went home to soak my poor feet, heat up a can of tomato soup, and take Groucho out for a drag.

In June, the gigantic Consumer Electronics Show came to Chicago, taking over all three floors of the convention center and every trade show model in town. Sanyo hired me to pose next to a wall of car radios and lure buyers from Radio Hut and Pep Boys into the showroom. The guy in charge of the models taught us a few words of Japanese, none of which were useful in warding off the Japanese executives, who firmly believed that all of us models were hookers paid to entertain them, at the convention during the day and at their hotel at night.

On my first day, I was rescued from one small, insistent Japanese man by an American in a well-cut suit, who took the guy aside and spoke to him in Japanese. The Japanese man glared and shook his finger at me, and I prepared to be fired on the spot. But he walked away and my rescuer came over to talk to me.

“Sorry,” he said. “These guys have already been set up with girls, but Mr. Moto really likes you. I can’t promise he won’t be back. I’m Gerry,” and he stuck out a small, delicate hand. “When’s your break? Can I buy you a sandwich?”

Gerry was just a few inches taller than me and as adorable as a cocker spaniel; he looked like a human Rowlf the Dog from the Muppets. He had soft curly brown hair that he wore just long enough to be hip and a funny little matching mustache that I knew would tickle. His eyes were a startling sky blue, innocent, almost transparent. I wanted to take Gerry home, put him on the couch next to Groucho and snuggle and pet the two of them.

Gerry wasn’t a salesman, he was an engineer who had come along on this Chicago junket in case a buyer had a difficult technical question about a car radio, which never happened, so Gerry just hung around the Sanyo exhibit, looking at me. I looked back and we both smiled.

A sandwich in the basement of the Convention Center turned into evenings out in those wonderfully expensive Chicago restaurants I had been missing. Sanyo gave Gerry a generous expense account, which he spent taking me out to dinner, after making sure that all the Japanese execs were happily set up with their hookers.

“Do not date guys you meet at the conventions,’’ my agent Ann had warned me. “It’s unprofessional and when it ends, poof, you’re out a client.” But Gerry was young and cute and I was tiring of Campbell’s tomato soup. I insisted that he not talk to me during the day, and after dinner I made him come to my apartment. I did not want to run into my Japanese suitor at the Hilton or have to do the El ride of shame at dawn.

Gerry was twenty-eight, and from California, which I thought automatically made you cool. He was funny enough and smart enough and smitten with me, which I always find attractive. He was a born tinkerer, one of those kids who reads Popular Mechanics cover to cover and takes apart every electrical appliance in the house. After being hired by Sanyo, he decided on his own to learn Japanese. Gerry taught me several interesting Japanese curses then warned me never to use them within earshot of the Sanyo executives. (I wish I could remember how to say, “You are a man who has to buy a sheep to service your wife” in Japanese.) The best part was that after five days, Gerry went back to California, leaving Groucho and me with a nice assortment of doggie bags from fancy restaurants.

I was pleased but not surprised when Gerry called to invite me to California for the Fourth of July. Summer is Chicago’s second worst season, when the sodden heat rolls off Lake Michigan accompanied by the smell of alewives, their fishy life cycle complete, dying and rotting by the millions on the shore. My sweet little studio was stifling; I would have gone anywhere that wasn’t a hundred degrees. The one girlfriend I had made, a model I met in an “Acting for Commercials” class (we bonded when we found out that the lech of a teacher had offered both of us free private tutoring, sessions that were very hands on) had married and moved to the suburbs. I didn’t want to spend the Fourth drinking cheap beer in Frank the photographer’s loft, which was as un-air-conditioned in the summer as it was unheated in the winter. I was hot and sticky and lonely.

I wasn’t in love. I wasn’t bedazzled as I had been with James. But I liked Gerry: he was cute, he made me laugh, and was okay in bed. So I said yes and Gerry sent me a ticket. I dozed on the plane out to California, dreaming of devouring hot dogs and hamburgers on the beach, gazing out at my old friend, the Pacific Ocean, and cuddling on a blanket with Gerry as a million fireworks exploded above our heads: a perfect Fourth of July.