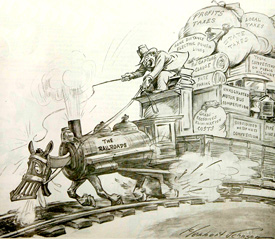

Caution! Danger Ahead!

Trains were quickly losing passenger and freight revenue to automobiles between 1920 and 1929. In this 1931 article from the Post, Edward Hungerford, who was considered an authority on railroad history, is nostalgic for the once-popular railroad. In this abridged version, Hungerford suggests railroaders must unite to combat the competition.

[See also: “The Looming Crisis in Mass Transit” from our Jul/Aug 2012 issue.]

CAUTION! DANGER AHEAD!

January 31, 1931—A young man entered St. Lawrence University at Canton, New York, last autumn and confessed that he had never ridden upon a railroad train. One of the officers of the university, an ardent railroad fan, was most interested in this young man and took him, not long ago, for a ride on the local train to Ogdensburg. The boy said that he enjoyed the experience.

There are many boys and girls like this in American colleges today. In my day almost every boy knew the railroad and loved it. But the younger generation today begins to know the railroad as a tradition rather than as a practical or a really close-at-hand necessity.

Not long ago a railroad president went out into the Middle West to the dedication of a railroad station. When it was nearly over, a local banker approached the railroad president and congratulated him upon the elegance of the new building.

“Quite a monument to the railroad passenger business,” said he, in his impressive, bankerish way.

“Mausoleum would be a better word for it today,” replied the railroader.

He was thinking, rather sadly, of that former great factor in American railroading that of late has been slipping pretty rapidly. From a high peak of $1,305,000,000 in passenger-traffic revenues in 1920—the high record of all time—it descended, in an all too brief decade, to $780,000,000 in 1929. Slowly at first; just lately with alarming rapidity—toboggan-slide fashion.

It has been suggested that the present emergency is large enough to call a railroad convention-presidents, vice presidents and other high executives to continue in session for a week, if necessary, and to thrash out some of the problems that are so vexing to the business as a whole.

At this convention of railroad executives various questions would be pressed:

What shall be the attitude of the railroads toward highways and toward the waterways?

Shall they advocate regulation of the length, weight, and speed of motortrucks and coaches because of their destructive effects upon the highways and the dangers to which they expose private motorists?

What of taxing very heavily such vehicles?

How about meeting the competition of trucks by pick-up and delivery service from the door of the shipper to the consignee?

How about this question of lowered fares?

No battle was ever won by an army not sure of its course and reasonably sure of final victory. Cooperation is vastly more than a word, or a group of words.

It might be possible for the railroads to take a leaf out of the big book in the White House and appoint some sort of capable joint commission to make a careful study of the entire problem in all its many phases. The result of such a study, made by careful and experienced, yet progressive, men should also clear the present atmosphere. It is commended both to the rail carriers and to that far-reaching and powerful organization, the American Railway Association.

The American railroader goes his way slowly—sometimes too slowly. He is facing a real crisis, unquestionably. He has faced other crises—borne of them much more portentous than this one—and has come through them safely and with a smiling face. The present situation is by no means hopeless; the railroads have not ceased to be the very backbone of the nation’s transport system. It is the yellow signal that is displayed, not the red. Caution, not danger.