Horror for the Whole Family: Halloween Books for All Ages

Halloween is upon us once again. Last year, the Post looked at the question, “What’s the right horror film for the whole family?” And while staying in for movies is still an excellent choice for this spooky season, especially with the pandemic still present, films aren’t your only choice for eerie entertainment. So the new question becomes, “What are the right horror reads for the whole family?”

Every family’s view of content is different, and every family has a different standard for when it’s okay for the kids to indulge in scary fare. What we have here are some baseline recommendations, standout books that you might check out as starters, along with some appropriate ages. Again, your own idea of what’s appropriate and when may vary, but that’s why comment sections were created.

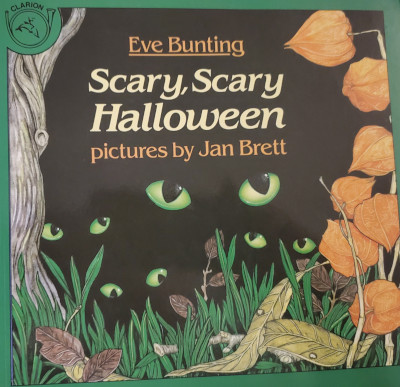

1.The Littles (9 and under): Scary, Scary Halloween by Eve Bunting and Jan Brett (1988)

Halloween-themed picture books abound, with lots of great, funny reads like Goblin Walk, but this one is a superlative effort from two huge talents. Eve Bunting has more than 250 books to her credit; she moves as easily from fiction to non-fiction as she does from picture books to novels. Jan Brett has been writing and drawing books for kids since the 1970s, and she’s received effusive praise for her lovely, intricate art. Scary, Scary Halloween brings them together in a delightful way, with rhyming verse and outstanding visual renditions of a scary Halloween night. An unseen narrator talks of monsters stalking through the neighborhood before the story takes not one, but two, surprise twists. It’s a great one to read to the little ones, and to have them read back to you as they get bigger.

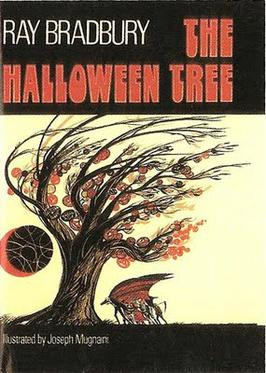

2. Kids to Tweens: The Halloween Tree by Ray Bradbury (1972)

Let’s be clear: Ray Bradbury’s The Halloween Tree is for EVERYONE, but it serves this particular demographic extremely well. Bradbury is, of course, one of the most exalted names in science fiction and fantasy, but he might also be the King of Halloween. His loving and nuanced takes on the holiday cause his name to appear repeatedly (and deservedly) on this list. The Halloween Tree is a touching story about friendship that also delves into the history of the holiday and its antecedent, Samhain. After a boy named Pipkin disappears, eight of his friends come together with the strange Mr. Moundshroud to travel through time to find their friend; along the way, they learn about the traditions of the Greeks, Romans, and Celts, visit medieval France, and witness what happens at Mexico’s Day of the Dead celebration. When the cost of saving Pipkin becomes clear, his friends come together for their friend in a moving finale.

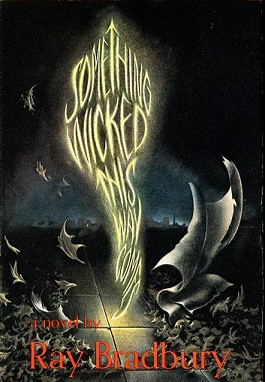

3. Teens: Something Wicked This Way Comes by Ray Bradbury (1962)

Today’s teens have access to a steady diet of horror material in both print and film; between libraries and streaming services, there’s not a lot that they haven’t already seen. That’s what makes Something Wicked This Way Comes special, in a way, because they might not have seen it. Bradbury’s 1962 masterpiece is all about the transition from youth to adulthood, while also baking in the regrets of age. When a strange carnival arrives in Green Town, Illinois on October 23, 13-year-old best friends Will Halloway (born one minute before midnight on October 30) and Jim Nightshade (born one minute after on October 31) are drawn into its orbit. At first, only Will and Jim seem aware of the unnatural events unfolding from the Cooger & Dark’s Pandemonium Shadow Show, but they find an unexpected ally in Will’s 54-year-old father. You can smell the autumn air in Bradbury’s rich descriptions of the season. The story, by turns wistful and terrifying, is one of the gold standards of dark fantasy. Teens can easily identify with the protagonists, as one of the primary forces in their own lives is the pull of adulthood.

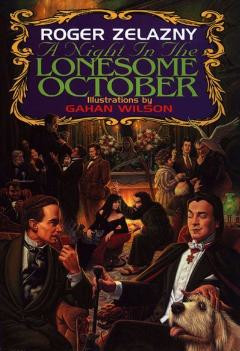

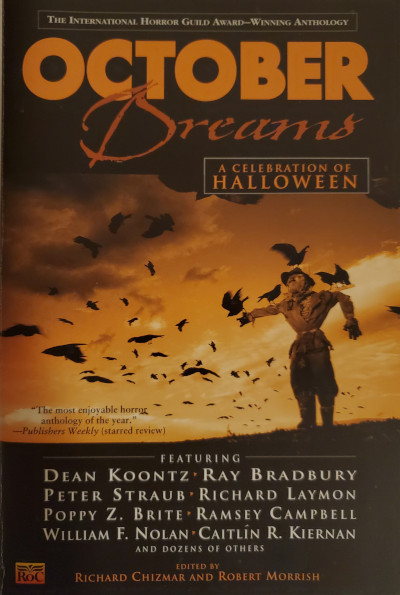

4. Adults: A Night in the Lonesome October by Roger Zelazney (1993) and October Dreams: A Celebration of Halloween (edited by Richard Chizmar and Robert Morrish, 2000)

A Night in the Lonesome October (not to be confused with Night in the Lonesome October by Richard Laymon, which is great in its own right) is creepy, funny, delightful, and demented. Zelazney was the celebrated writer of the bestselling The Chronicles of Amber series and dozens of other works; he won the Hugo Award six times and the Nebula three. 1993’s ANITLO was one his favorites of his own work; it was also his last novel, as he died in 1995. But what a great final statement it is. After an introduction, the 31 remaining chapters each take place on one day in October leading to Halloween in late 1800s London. The story is told from the point of view of Snuff, the canine companion and magical familiar of one Jack the Ripper. However, Jack is actually trying to save the world in a story that involves (either directly or by clever parody) the Lovecraft mythos, Dracula, Sherlock Holmes, the Wolf Man, the Frankenstein Monster, Rasputin, and more. The book is by turns haunting and hilarious, with Snuff and the other familiars alternately trying to help their masters save or destroy the world. Surprise alliances and betrayals abound, and it’s a real feat of imagination.

On the darker side, the 2000 anthology October Dreams: A Celebration of Halloween is simply one of the best collections about Halloween ever put to print. Collecting short stories along with non-fiction Halloween reminiscences by a murderer’s row of talent, the book includes the likes of Bradbury, Dean Koontz, Poppy Z. Brite, Christopher Golden, Jack Ketchum, Gahan Wilson, Richard Laymon, Dennis Etchison, Ramsey Campbell, Peter Straub, and many more. At over 650 pages, it’s a slab of fiendish goodness.

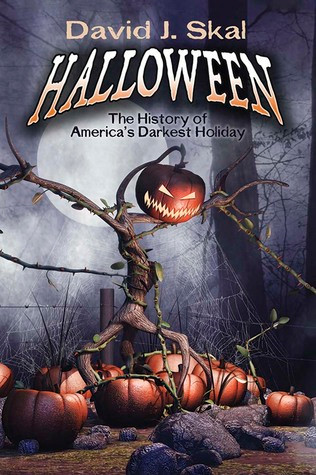

5. The Adult History Buff: Halloween: The History of America’s Darkest Holiday by David J. Skal (2016)

An October surprise bonus category! Yes, The Halloween Tree digs into the roots of the holiday, but this is a phenomenal book by one of the most authoritative writers on horror. Skal has written essential non-fiction like The Monster Show: A Cultural History of Horror, Hollywood Gothic, and Something in the Blood: The Untold Story of Bram Stoker, the Man Who Wrote Dracula. Here, he turns his keen insights to Halloween itself. Skal’s real talent lies in engaging a topic on both the macro and micro level, juxtaposing how that topic impacts the culture as a whole while also using laser-precise examples to show just how deeply that impact runs. Skal’s examination runs the gamut from the early Celtic days to a present where we (in non-pandemic years) spend about $9 billion celebrating the holiday.

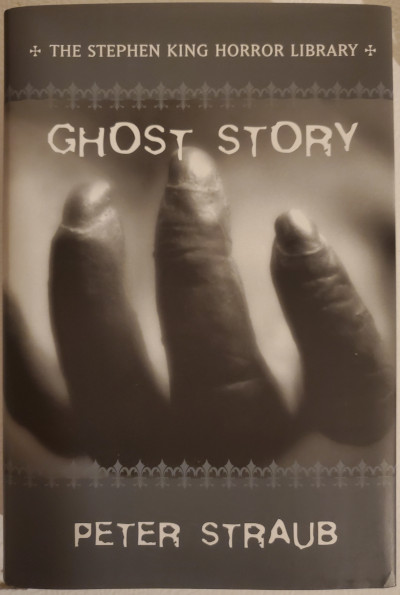

6. Grandparents: Ghost Story by Peter Straub (1979)

This one goes off theme just a tiny bit, but bear with it. Yes, Ghost Story takes place across multiple time periods with one of the most climactic sequences occurring during a blizzard. But it is one of the grand champions of scary storytelling, and the initial protagonists are a group of older gentlemen and one gentleman’s wife. With many mature main characters and Straub’s deep appreciation for the canon and history of American horror (references to Nathaniel Hawthorne and Donald Wandrei abound, and nods are clearly made to George Romero and Straub’s pal Stephen King), Straub crafts a particularly literary story that thrives on human emotion. There is some really dark stuff, but there are also seeds of hope, especially when the older men reach out to two other protagonists (one much younger) to help them navigate the terror that has them under siege.

And there you have it: like the film list, it’s a list to get you started (and to start discussions). Enjoy this very strange season, get lost in the books that you intend to read, and maybe, just maybe, leave a light on.

Featured image: Marsan / Shutterstock

Guide to the Archive: Ray Bradbury

Between 1950 and 2009, The Saturday Evening Post published 13 short stories by Ray Bradbury, the science fiction and fantasy author best known for his novel, Fahrenheit 451.

Saturday Evening Post members can enjoy reading these stories in our digital archive, along with fiction by other greats such as F. Scott Fitzgerald, Dorothy Parker, and Jack London. Subscribe today.

Stories and Poems by Ray Bradbury

“The World the Children Made,” September 23, 1950, page 26

“The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms,” June 23, 1951, page 28

“The April Witch,” April 5, 1952, page 31

“They Knew What They Wanted,” June 26, 1954, page 22

“Summer in the Air,” February 18, 1956, page 28

“Good-by, Grandma,” May 25, 1957, page 28

“The Happiness Machine,” September 14, 1957, page 43

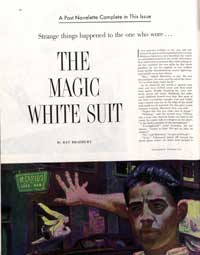

“The Magic White Suit” [novelette], October 4, 1958, page 28

“Forever Voyage,” January 9, 1960, page 16

“The Drummer Boy of Shiloh,” April 30, 1960, page 22

“The Beggar on the Dublin Bridge,” January 14, 1961, page 28

“The Prehistoric Producer,” June 23, 1962, page 18

“Fathers and Sons Banquet” [poem], May 1974, page 59

“Up from the Deep,” September 1981, page 12

“America” [poem], July/August 2009, page 35

“Juggernaut,” September 1, 2009, page 29

Video Image Credits

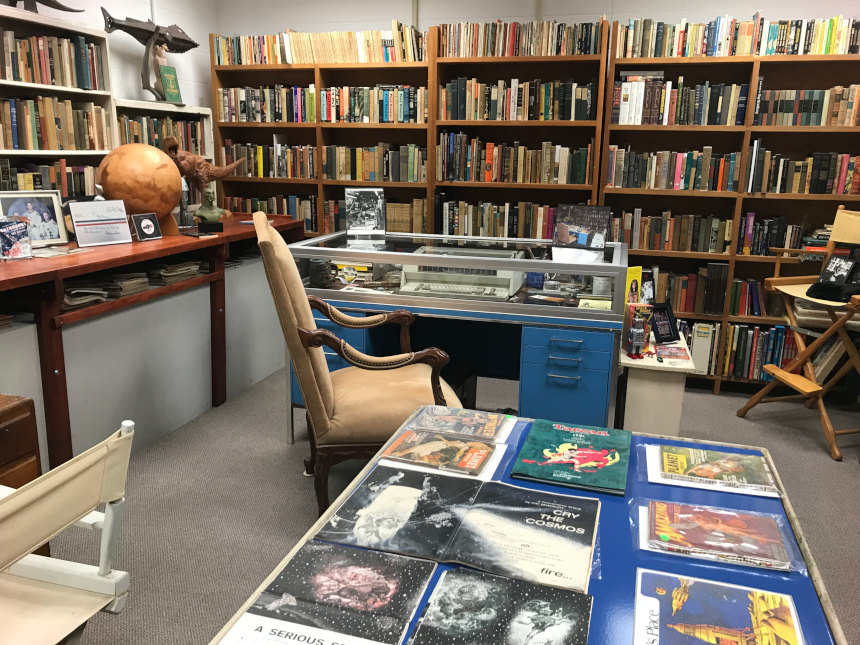

0:13 – Image of Center for Ray Bradbury Studies, IUPUI (photo by SEP staff)

0:25 – New Yorker cover: Alamy

0:45 – All images associated with EC Comics are owned and licensed by William M Gaines Agent, Inc. © 2019, All Rights Reserved.

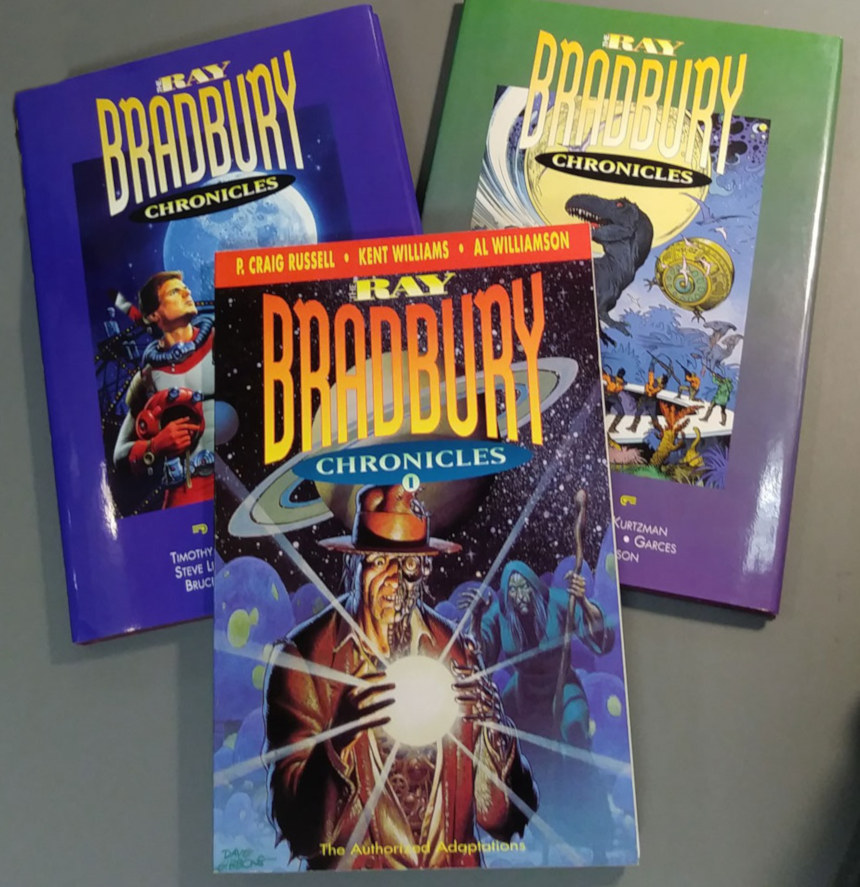

0:56 – Copyright © NBM Graphic Novels

1:46 – Ray Bradbury (Wikimedia Commons, MDCarchives via the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license)

Ray Bradbury: Comic Book Hero

“It was like Moses parting the seas.” That was how one eyewitness described the scene. By 2010, Comic-Con San Diego had ballooned from its humble 1970 origins into the massive carnival it is today, with tens of thousands of conventioneers dressed as their favorite heroes and heroines, each hoping to play the latest video game, handle exclusive merchandise, maybe catch a glimpse of an A-list star. Yet in all the chaos, the countless Batmen, Wonder Women, and stormtroopers parted to make way for the biggest name in the building. Over a thousand people would cram into the conference room where he would field questions.

He was no hot young actor or starlet, nor a director of the latest comic book to get a film treatment. At almost 90 years old, Ray Bradbury could only smile as his wheelchair was pushed through the parting throng of gushing, gawking fans.

The scene in 2010 was different from the one in 1939 at the great-granddaddy of all cons, The World Science Fiction Convention in New York. Bradbury, then only 19 years old, had to borrow money from his good buddy (and, later, his literary agent) Forry Ackerman to ride a Greyhound across the country and stay at the local YMCA. At this gathering, the teen rubbed shoulders with the likes of Isaac Asimov and John W. Campbell, editor of Astounding Stories of Super-Science and a leader in the burgeoning science fiction genre, but ultimately failed to sell any of his stories to the numerous publishers he visited.

Thirty-one years later, Bradbury was asked to speak at a new conference venture in San Diego. In 1970, all of 300 people attended the Golden State Comic-Con, as it was then known, and no one knew that it would soon evolve into a world-famous annual comic event, known simply and without need of explanation as Comic-Con. Bradbury was well-established in the world of science fiction and fantasy by then, having published the modern classics Fahrenheit 451 and The Martian Chronicles, the former already a mainstay of high school English classes.

There was only one reason for someone as successful and well known as Ray Bradbury to attend a tiny gathering that the rest of the world ignored: He just loved comics. As he later said of his childhood comics, “Without all this splendid mediocrity, this sublime and wondrous trash in my background, I don’t think I would be any sort of writer today.” Comics created Bradbury, and in turn he propelled the medium forward.

Other writers had seen their works illustrated, but it was Bradbury who first embraced comic books and respected them in a way more easily understood in today’s Internet-based culture. He envisioned graphic novels decades before they existed, defended comic books at a time when they were being burned in public, and supported Comic-Con from that first gathering in 1970 through the end of his life. He never cared whether what he liked was trendy or cool; he simply did what he loved.

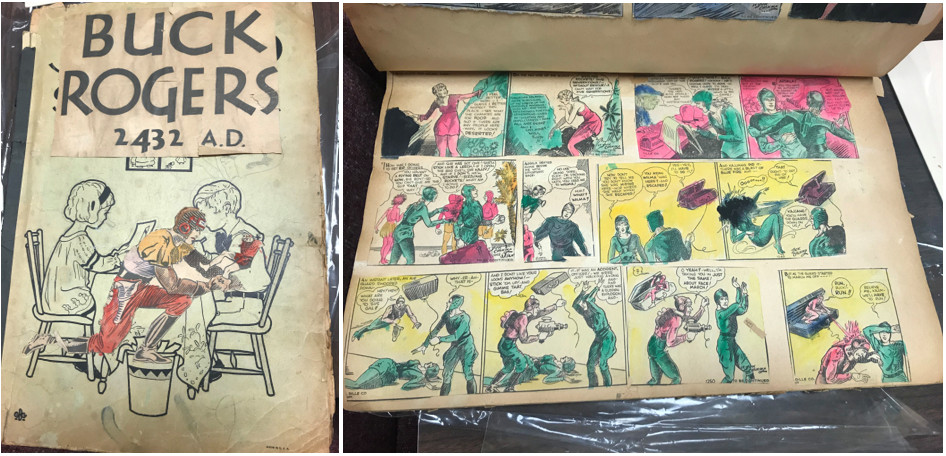

The World the Children Made

As a boy growing up in Waukegan, Illinois, a city he would immortalize as Greentown in Something Wicked This Way Comes and Dandelion Wine, Bradbury obsessively scrapbooked his heroes from the newspaper comic strip pages. These included the wonderfully illustrated worlds of Phil Nolan and Dick Calkins’ Buck Rogers, Alex Raymond’s Flash Gordon, and Hal Foster’s Tarzan and Prince Valiant. Hal Foster’s art depicted fantasy realms in nonexistent lands. Buck Rogers and Flash Gordon were Earthmen in space who introduced an entire generation of children to faraway galaxies and literally out-of-this-world inventions. In an era when horses were still hauling blocks of ice and plenty of homes went without electricity, these cartoons predicted a world of rocket ships, ray guns, and jetpacks. While science fiction was starting to pop up in movies, it was the funnies that brought the genre daily to the masses. They also planted the seed in a boy’s mind that sprouted one of the most prolific fantasy and science fiction careers of the 20th century.

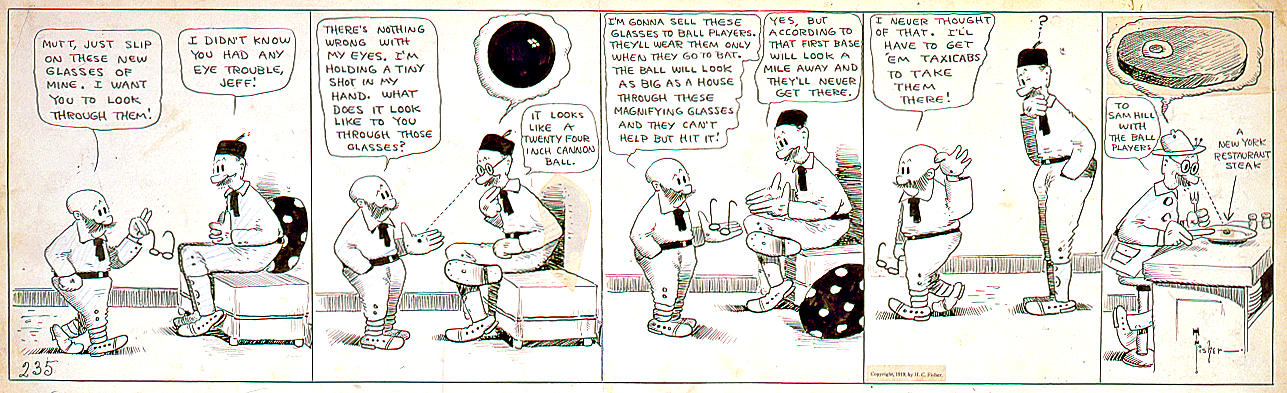

In the late 1920s and early ’30s, there were no comic books per se. Occasionally a publisher would release a bound volume of Mutt and Jeff or Bringing Up Father, but the roughly 8-x-10-inch comic books selling for a dime at the local newsstand would not come into being until Famous Funnies debuted in 1934, edited by Max Gaines. Indeed, knowing that children kept the funny pages and threw out the rest of the paper convinced Gaines that comics could be sold directly to consumers.

Starting in 1929, Bradbury created his own comic anthologies from newspaper strips, cutting out his favorites from the Waukegan News-Sun and the Chicago newspapers and pasting them into scrapbooks, sometimes adding his own artistic flair by coloring them himself. He did this with religious devotion every day for years, pausing only briefly as a nine-year-old caving to peer pressure. As he explained decades later in a piece published in the guide to San Diego Comic-Con 1980, “Kids made fun, I took on embarrassment, and tore up the strips. A month later, empty, I burst into tears, asked myself what was wrong. The answer: Buck Rogers was gone, and life not worth living.” He soon began collecting again and never looked back. Moreover, he learned to never care what the world thought of his “low-brow” tastes. As an adult, he not only kept his collection of childhood strips —24 of his scrapbooks are still intact at the Center for Ray Bradbury Studies in Indianapolis — but he would defend comics at a time when they were neither hip nor valued as art.

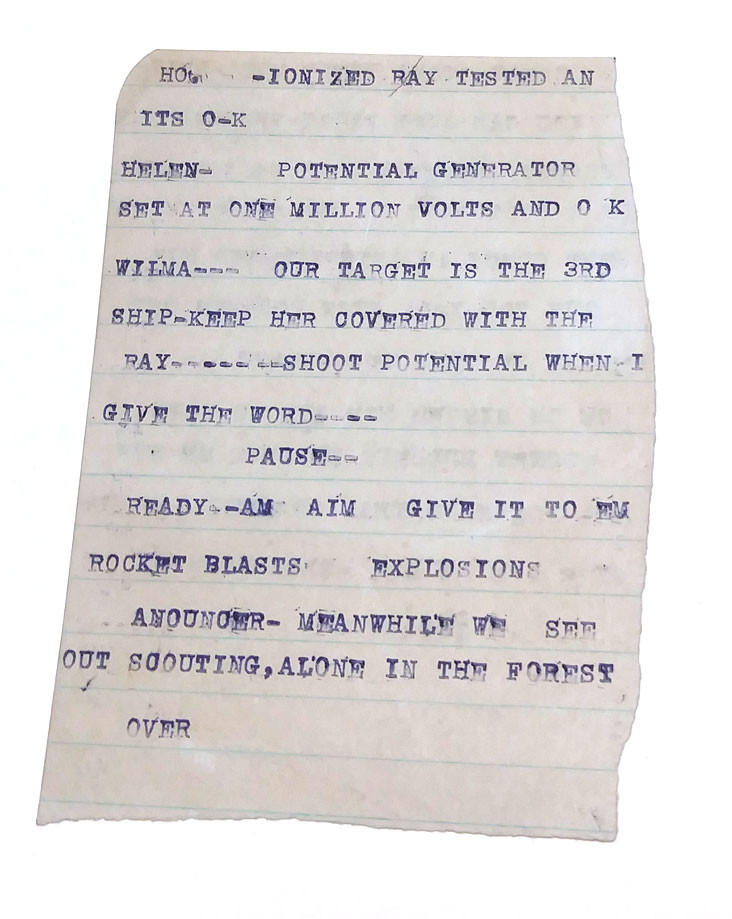

Strictly speaking, the first time the comics industry paid off for Bradbury was in 1932, when the future writer was a mere 12 years old. His family had relocated to Tucson, Arizona, and Bradbury found work as an errand boy at a local radio station. A bold child, Bradbury walked to the studio of KGAR and asked for a job. Radio shows like Chandu the Magician were another joy of Bradbury’s childhood, and dozens of his stories would later appear on radio classics like Lights Out and X Minus One.

KGAR employed the boy to empty out ashtrays and fetch food for the men. After two weeks acting as their gofer, the workers asked if he would like to be on the air. He zealously accepted. With other children, he read the adventures of The Katzenjammer Kids and Tailspin Tommy, complete with funny voices and sound effects. KGAR paid him with movie tickets, the films of Lon Chaney and Douglas Fairbanks being another love of his.

While in Tucson, the Bradburys bought their youngest a toy dial-a-letter typewriter as a Christmas gift. From the age of 12, he typed fantastic stories, including his own fan-fiction continuation of Edgar Rice Burroughs’ John Carter of Mars. Bradbury’s pre-teen writing is especially impressive when you consider how tedious the dial-a-letter typewriter was: He had to dial in and then type each letter, one at a time.

As a 17-year-old, after the family had moved to Los Angeles, Ray Bradbury joined a local science fiction club. There he met Ray Harryhausen, Forry Ackerman, and Robert Heinlein, who would become (respectively) a pioneer in stop animation visual effects; an editor, promoter, and literary agent of the science fiction genre; and “the dean of science fiction writers.” Heinlein helped the young writer get his first short story in a professional magazine, Script (the editors paid Bradbury with three free copies).

After the war, he wrote increasingly about space travel, which was becoming more likely and less theoretical as both America and the Soviet Union experimented with rockets. He speculated about interstellar travel in haunting tales like “Kaleidoscope,” “The Rocket Man,” and “I, Mars.” He rose quickly in the world of fantasy and science fiction magazines like Weird Tales and Thrilling Wonder Stories, eventually gaining a reputation as the “Poet of the Pulps.” People took notice of his talent, one of them a young comic book editor named Bill Gaines.

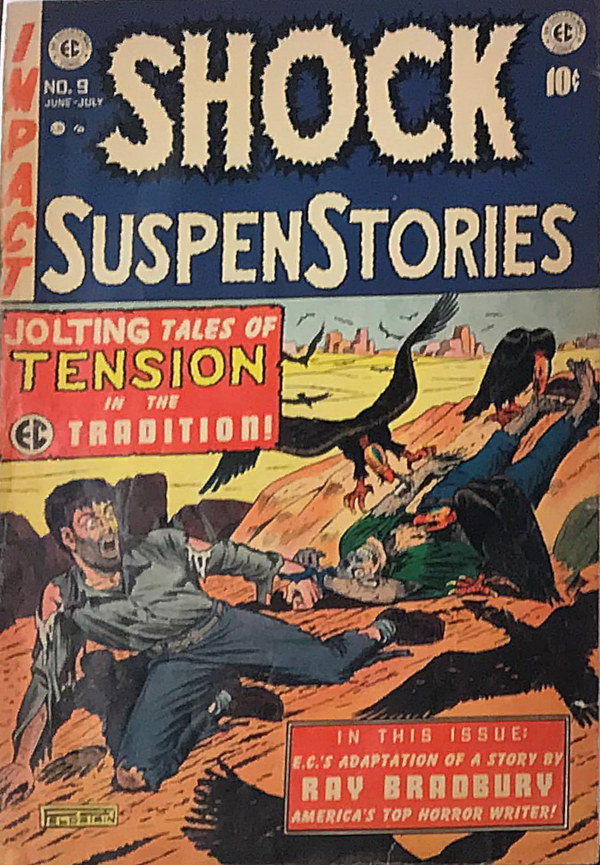

The May/June 1952 issue of Weird Fantasy, one of the many titles published by E.C. (Entertaining Comics), included the Wally Wood-illustrated story “Home to Stay,” which appeared to be based on Bradbury’s “The Rocket Man” and “Kaleidoscope.” Previous issues of E.C. Comics’ The Vault of Horror and The Haunt of Fear showcased plotlines reminiscent of two other Bradbury stories, “The Emissary” and “The Handler.” Friends and colleagues brought these stories to his attention.

Bradbury was always highly defensive of his work. He took action by sending this tactful letter to Gaines:

Just a note to remind you of an oversight. You have not as yet sent on the check for $50 to cover the use of secondary rights on my two stories. … I feel this was probably overlooked in the general confusion of the office work, and look forward to your payment in the near future.

Gaines realized it made sense to pay the writer whose star was rising in the world of science fiction. He replied in kind: “Although we do not agree with your conclusions, … we are enclosing our check for $50, without intending to agree with your contentions.”

This minor spat between Bradbury and Gaines could have ended here if not for the author’s respect for what E.C.’s team of artists had done with his works. Though in his 30s, Bradbury was still the kid from Waukegan with a basement full of newspaper strips, and he was genuinely thrilled to see his stories turned into comics. He ended his initial letter to Gaines with this coda: “PS Have you ever considered doing an entire issue of your magazine based on my stories in DARK CARNIVAL, or my other two books THE ILLUSTRATED MAN and THE MARTIAN CHRONICLES?”

At this point, these were the only three books Bradbury had published, all of them collections of short stories. The prescient writer was calling on Gaines to create something that didn’t yet have a name: the graphic novel.

Gaines passed on illustrating entire Bradbury books, but his company eventually would adapt 27 of his best-known tales, including such classics as “The Lake,” “The Sound of Thunder,” and “There Will Come Soft Rains.” In a way, E.C. Comics did create Bradbury’s graphic novels, as most of these works would later be collected in two paperbacks, The Autumn People (1965) and Tomorrow Midnight (1966). Bradbury routinely wrote letters of praise not just to Gaines but also to the artists — Al Feldstein, Wally Wood, Joe Orlando, Will Elder, and Jack Kamen.

Besides seeing his works drawn by some of the best in the business, Bradbury’s name also appeared on the covers. (“In this issue: E.C.’s adaptation of a story by Ray Bradbury, America’s top horror writer!” He was also America’s “top science-fiction writer” depending on the genre of the comic.) His was the only writer’s name E.C. Comics stamped on its covers.

But Bradbury soon asked that his name not be so prominently displayed. In the early ’50s, comics were considered at best silly, juvenile, and not worthy of “real writers.” At worst they were thought to poison children’s minds. In January 1953, Bradbury wrote a long, apologetic letter to Gaines, asking that his name be removed from upcoming covers of Entertaining Comics. He painfully explained that this request was purely business, not personal. He had recently “graduated to the slicks,” meaning that he was finally breaking out of the pulps of Weird Tales and Planet Stories and into more respected, better-paying titles like The Saturday Evening Post and the Truman Capote-edited Mademoiselle. His association with low-brow comics would not enhance his reputation.

The Irritated People

It may seem disappointing that Bradbury, famous for standing up for mass culture and being opposed to censorship, seemingly gave in to peer pressure, but this would be a simplistic way of thinking. Surrendering to the trends of the times would have meant simply abandoning E.C. Comics, considered by many social reformers to be the worst of the worst comic books, with their shocking covers and gory tales of death and dismemberment. Bradbury continued to work with Gaines and his stable of artists until their magazines folded; his asking they take his name off the covers was a compromise. “By all means,” Bradbury wrote, “exploit my stories and my name INSIDE your magazines, all that you wish.” Given that they paid him only $25 per adaptation (about $250 in today’s money), it’s clear that he was not getting much financially from a partnership that could only jeopardize his reputation. In our modern era, when top talents like Stephen King and Margaret Atwood eagerly turn their writing into graphic novels, it needs to be remembered that this was by no means a trendy or even wise move for a writer in conformist 1950s America. Bradbury wanted E.C. Comics to adapt his works simply out of childlike glee.

In the end, Bill Gaines and E.C. Comics found themselves in the crosshairs of one of America’s more hysterical movements: the comic-book burnings. In 1953, respected psychiatrist Fredric Wertham published Seduction of the Innocent, a best-selling book that claimed comics caused juvenile delinquency and homosexuality. In his denunciation of comic books, Wertham claimed, “Special emphasis is given in whole series of illustrations to girls’ buttocks. … Such preoccupations, as we know from psychoanalytic and Rorschach studies, may have a relationship also to early homosexual attitudes.”

By 1954, churches, schools, and respected civic organizations were leading bizarre purges, gathering children in public squares to throw their “filthy” comic books onto bonfires. The scenes must have reminded Bradbury of Fahrenheit 451, which he had just published.

Bradbury never forgot this odd episode of American history. In the introduction to Ray Bradbury Comics #4 (more on that publication in a moment), he wrote: “I was … put upon by professional psychologists and social reformers who … told us that fantasy was bad for children. … One learned professor managed to get quite a few comic books banned for many years.”

In that same issue, he added the following line to his previously published story “Usher II”: “All the tales of terror and fantasy, and for that matter, tales of the future were burned heartlessly. They began by controlling books of cartoons.”

Next Stop, the Stars

Bradbury’s career in comics continued to thrive as the industry itself grew and gained respectability. In 1970, he was asked if he would be willing to put in an appearance at a small convention happening in San Diego. The very first Comic-Con was so small that it fit in the basement of the U.S. Grant Hotel. Now called Comic-Con International: San Diego, the world’s largest comics convention attracts about 130,000 people annually. Bradbury returned to San Diego’s Comic Con every year until 2010, his declining health making the trip unfeasible. He loved the attention and happily signed autographs.

In 1972, he almost realized his dream of having his own newspaper comic. He commissioned Doug Wildey, who would create the Jonny Quest series, and his lifelong friend painter Joe Mugnaini, cover art designer for many of Bradbury’s books, to illustrate The Martian Chronicles. Bradbury had hoped for a weekly Sunday strip, but unfortunately, no distributors picked it up. Only the L.A. Times ran with it, and then it was only a three-page spread of the story “Mars Is Heaven” in the Times’ West Magazine.

It wasn’t until the 1990s — 50 years after he first suggested book-length adaptations of his stories — that Bradbury saw this vision come true. The Bradbury graphic novels began, oddly, as the result of a video game. He collaborated with writer and software developer Byron Preiss to turn his two best-known works, Fahrenheit 451 and The Martian Chronicles, into games. Preiss next gathered a team of artists to publish The Ray Bradbury Chronicles, a limited-edition hardcover series of graphic novels of his best-known stories. This same team developed Ray Bradbury Comics, numbered issues published by the short-lived Topps Comics. While Topps will always be better-known for its trading cards, it did briefly have a comic book division in the mid-’90s, a time when many companies tried their hand at graphic novels. Each issue of Ray Bradbury Comics started with an introduction from Ray himself and included reprints from the E.C. years, plus new adaptations. This being Topps, each edition also came with three trading cards depicting scenes from various Bradbury stories.

Between 2009 and 2011, Hill & Wang published Fahrenheit 451, The Martian Chronicles, and Something Wicked This Way Comes as graphic novels. That they were published by Hill & Wang shows how much more respected Bradbury and comics had become — this was the same company that printed an illustrated version of the 9/11 report.

In 2010, Bradbury graciously accepted the Comic-Con San Diego Icon Award, granted to people who are “instrumental in creating greater awareness of and appreciation for comic books and related popular art forms.” It was a fitting tribute to a man who did so much to make science fiction and comics the respected art forms they are today, and who stood by comics at a time when many were calling for them to be outright banned.

The world can now see comics the way a little boy in Waukegan once did 90 years ago. As Bradbury once said of comics finally being accepted as art:

And anyway, it appears we are vindicated. The Pop Art people come along, late in the day, to tell us about comic strips and characters. But we send them packing. Our answer is: we knew it all the time! Don’t tell us about what we have already loved and loved well!

—from the introduction to the Autumn People, 1965

Want to learn more about Ray Bradbury’s life and legacy? Read some of his short stories that appeared in the Post, plus our one-on-one interview with the man himself in 2009. Also check out Indiana University’s Center for Ray Bradbury Studies and support the Ray Bradbury Experience Museum in Waukegan, Illinois.

Featured image: All images associated with E.C. Comics are owned and licensed by William M Gaines Agent, Inc. © 2019, All Rights Reserved.

The Post Mourns Ray Bradbury

The Post mourns the passing of one of the great names in American fiction — and one of its most important contributors.

Ray Bradbury published his first story in the Post 62 years ago. “The World the Children Made” was followed by 15 other stories, one, “Love Contest,” published under the pseudonym Leonard Douglas and the last being “Juggernaut,” which we printed in 2009.

Bradbury, who was 91, had been a member of the Post’s fiction board for the past few years. He wrote like nobody else, and he influenced countless other American authors. He was and will be imitated, but very few have been able to recreate his balance of magic, realism, humor, and mystery.

Just before his last story appeared in the Post, he agreed to an interview, which you can read here.

One-on-One with the Author: Ray Bradbury

In 2009, Post writer Shirrel Rhoades spoke with Ray Bradbury, the legendary fantasy writer and an esteemed member of The Saturday Evening Post’s Fiction Advisory Board. In honor of Bradbury, we are reprinting that interview. You can also read his short story “Juggernaut,” mentioned in the article. –Post Editors

Bradbury is a wizard with words. Dandelion Wine was a magical evocation of childhood. Something Wicked This Way Comes offered chills that outdid the Brothers Grimm. The Martian Chronicles took us to other worlds of imagination. The Illustrated Man was a paean to storytelling. Fahrenheit 451 was a love affair with books.

“Back when I was 12 years old, I was madly in love with L. Frank Baum and the Oz books, along with the novels of Jules Verne and H.G. Wells, and especially the Tarzan books and the John Carter, Warlord of Mars books by Edgar Rice Burroughs. I began to think about becoming a writer at that time,” recalls Bradbury. “Simultaneously, I saw Blackstone the Magician on stage and thought, ‘What a wonderful life it would be if I could grow up and become a magician.’ In many ways, that is exactly what I did.”

His first published book was a collection of short stories called Dark Carnival, which set the tone.

Bradbury collaborated with Charles Addams on the creation of that macabre family that eventually took Addams’ name. Bradbury originally called them the Elliotts. His first story about them was “Homecoming,” published in the October issue of Mademoiselle magazine in 1946, replete with Addams’ illustrations.

However, despite being a fantasy writer, his ideas are often grounded in reality. When we asked him about “Juggernaut,” the original short fiction in this issue of the Post, he had this to say:

“The story ‘Juggernaut’ came to be because I happened to grow up among several different people who had physically moved their houses from one location to another. This always fascinated me and made me want to write a story about it.

“I was especially inspired about 60 years ago, in downtown Los Angeles, when I saw a house being moved down a big hill. Someone had painted some Indian symbols on the wheels, which I found fascinating, and I knew I must write something about this.”

In addition to a wall filled with awards and accolades, even a star on Hollywood’s Walk of Fame, Bradbury received, in 2007, a special citation from the Pulitzer board for his “distinguished, prolific, and deeply influential career as an unmatched author of science fiction and fantasy.”

He likes to tell the story of his childhood meeting with a carnival performer billed as Mr. Electrico, a man who changed his life by tapping him with an electrified sword, saying, “Live forever!”

“I thought that was a wonderful idea, but how did you do it?” he reflected at the time.

We know. Through his wondrous books and stories, he will live on with readers forever.

Ray Bradbury: The “Juggernaut” Writer

On August 22, Ray Bradbury will celebrate his 89th birthday. By a happy coincidence, The Saturday Evening Post is featuring a new story by Bradbury—“Juggernaut”—in the September/October issue.

The Post’s collaboration with Bradbury traces back to 1950, when we published his short story, “The World the Children Made.” All tolled, the Post has published 14 short stories and two poems—just a small part of the man’s output, which is somewhere around 500 published works.

Anyone wanting to know American literature or wanting to be an American writer must read Ray Bradbury. He speaks to a part of the American spirit that no other writer has addressed so directly. Part poetry, part elegy, sentimental, fantastic, but usually rooted in everyday experiences.

“It was summer twilight in the city, and out front of the quiet-clicking pool hall three young Mexican-American men breathed the warm air and looked around at the world. Sometimes they talked and sometimes they said nothing at all, but watched the cars glide by like black panthers on the hot asphalt or saw trolleys loom up like thunderstorms, scatter lightning, and rumble away into silence.”

This is the first paragraph of “The Magic White Suit,” which the Post published in 1958. It tells of five men with identical height and proportions who combine their money to buy a special white suit, which they take turns wearing.

“There on the dummy in the center of the room was the phosphorescence, the miraculously white-fired ghost with the incredible lapels, the precise stitching, the neat buttonholes. Standing with the white illumination of the suit upon his cheeks, Martinez suddenly felt he was in church. White! White! It was white as the whitest vanilla ice cream, as the bottled milk in tenement halls at dawn. White as a winter cloud all alone in the moonlit sky late at night.”

Around 1990, movie director Frank Zuñiga worked with Bradbury to film the short story. He remembers meeting Bradbury at his office:

“In the reception area, where a secretary might sit, there was a life-sized, stuffed version of Bullwinkle the Moose. The rest of the room was books. Books on top of books, stacked from floor to ceiling. We had to walk this narrow path between them back to his own desk. There were even more books, and three old typewriters. They weren’t even electric—and this was in 1990! Three manual typewriters, each holding a page of typing. He told me, ‘When I get tired working on one story, I move to the next typewriter.’”

He mastered his craft on such typewriters. Living in Los Angeles during the Depression, he graduated from high school and began selling newspapers to support his family. His college, he has said, was the 10 years he spent in the LA libraries, pounding out stories on the ancient typewriters that rented for 10 cents an hour.

Bradbury said that the “The Magic White Suit” was based on a personal experience. At graduation, Bradbury’s parents gave him his first suit. It was used, and worn, and fit him poorly, but it was a suit. Only later did he learn that it was the suit his uncle had died in. “They hadn’t even sewn up the bullet hole,” he said. It was such a good story, Zuñiga didn’t have the heart to ask Bradbury if it was true.

For all his fantastic visions, Bradbury has lived a low-tech life. He never drove. He preferred to be driven around LA or simply bike to his office or the studio. He never flew in a plane until he was 73, when he attended the premier of the movie, The Wonderful Ice Cream Suit. But he was always excited by innovation. “He was incredibly excited during the moon landing in ’69,” says Zuñiga. “It was a dream come true for him. He wished he could experience it himself, but he knew that was unlikely. So what he did was ask to visit the Chatsworth, California, site where the rocket engine was being tested. He stood on the pavement, safely out of range, but close enough for the sound and force of the engines to hit him and whip his clothes around his legs. He told me it was among the biggest thrills in his life.”

With the story “Juggernaut,” Ray Bradbury has now contributed to the Post for 60 years. And if he wants to write for another 60 years, The Saturday Evening Post will be glad to keep publishing his treasured stories.