In a Word: The Racist Origins of ‘Bulldozer’

Managing editor and logophile Andy Hollandbeck reveals the sometimes surprising roots of common English words and phrases. Remember: Etymology tells us where a word comes from, but not what it means today.

When you see the word bulldozer, you might conjure an image of a large yellow machine with caterpillar treads flattening everything before it with its steel-toothed blade. Or maybe your mind goes back to a smaller Tonka version of this mechanical behemoth that you played with as a child. Taken on its own, with no context, bulldozer might even call to mind some serene bovine scene, perhaps Ferdinand the Bull dozing among the daisies.

How jarring, then, to discover bulldozer’s horrible, violent beginnings.

Bulldozer (originally spelled bulldoser) first appeared in the run-up to the election of 1876. That was the final year of President Ulysses S. Grant’s second term in office, and he had unexpectedly declined to run for a third term. In his place, the Republican party put its support behind Ohio Governor and former U.S. Representative Rutherford B. Hayes, while the Democratic candidate was New York Governor Samuel Tilden.

This was an important election. All the former Confederate states had returned to the Union, post-Civil War Reconstruction was ongoing, and this was the first presidential election in which African-American men could vote for someone who wasn’t Ulysses S. Grant. The outcome of the election of 1876 would shape the future of the South for years to come.

The former slave owners and secessionists in the South knew it, and they weren’t about to sit back and let the North and their former slaves usurp their power and privilege. Despite three new federal laws in 1870 and ’71 designed to protect Black Americans from violence and coercion at the polls, many were bulldosed into silence. Bulldose was a slang term derived from either “a dose fit for a bull” or “a dose of the bull” — the second being a reference to the bullwhip. Bulldosers used physical violence against Black voters either to keep them from the polls or to intimidate them into voting Democratic.

Going into the election, in five states — Alabama, Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi, and South Carolina — a majority of registered voters were African American. One would expect, in a fair election, that the Republican candidate would easily take these states. But after the votes were tallied, Tilden had won the popular vote in Alabama and Mississippi.

The results in the other three states were even more unexpected. After counting had finished, both parties claimed victory in those states. On election night, Tilden was the presumed winner with 184 electoral votes, 19 votes ahead of Hayes and 1 vote away from holding a majority.

The 20 electoral votes of these states (plus Oregon) remained undecided for months as first the two parties and then the two houses of Congress launched separate investigations. Democrats and the Democratic-controlled House committee accused the Republicans of ballot stuffing and coercion. Republicans and the Republican-controlled Senate committee accused the Democrats of the same.

In the end, the presidential election was decided behind closed doors. In what came to be called the Compromise of 1877, the Democrats conceded the remaining electoral votes to the Republicans, making Rutherford Hayes our 19th president, but in return, federal troops were to be removed from the South, essentially ending Reconstruction and returning power to the same men who had controlled the South during the Civil War.

Though violent intimidation at the polls certainly continued, Southern officials found new ways to suppress the Black vote, including Jim Crow laws and grandfather clauses. Bulldosing took on the wider meaning of “to coerce or restrain by use of force,” and it was ripe for a more literal use when large, seemingly unstoppable machines came on the scene.

The machine we think of as a bulldozer was invented in the early 1920s, and by the initial months of the Great Depression, we start to find the term bulldozer in writing, with that Z further obscuring the word’s origins. The violent, racist origin of bulldozer is one reason many people now use the term earth mover to describe these massive machines.

If you’d like to learn more about the election of 1876 — including commentary from the Post while the election results were in flux — read “The Worst Presidential Election in U.S. History.”

Featured image: Andrey Yurlov / Shutterstock

The First Black U.S. Senator Argued for Integration after the Civil War

Despite a days-long outcry from Democratic senators attempting to block the first African-American member of the U.S. Congress from taking his seat, Hiram Rhodes Revels was finally voted in to the Senate along party lines 150 years ago today.

Revels had been appointed to his seat by Mississippi Republicans, as senators at the time were selected by the state legislature instead of by popular vote. Revels had served as an alderman in Natchez, Mississippi, having settled there after traveling the country as a minister, educator, and chaplain for the Union army. When he arrived in Washington, D.C. to be sworn in, Revels was met with protest from the minority Democrats.

“There was not an inch of standing or sitting room in the galleries, so densely were they packed,” according to The New York Times, “and to say that the interest was intense gives but a faint idea of the feeling which prevailed throughout the entire proceeding.” An atmosphere of fervent argument erupted in the chamber in those few days of deliberation over whether or not to allow the first black senator into the body, but the Times only hints at the insulting, racist language hurled at Revels and his defenders.

The official argument used against Revels was that he had not been a U.S. citizen for the nine years required to be eligible for the U.S. Senate. Even though Revels was born a free man — in 1827 — Democratic senators argued that the Civil Rights Act of 1866 had given the Mississippi alderman only four years of citizenship. Several Republicans held that this was an absurd argument, and that the Senate ought to vote Revels in and begin a new age of representation for African Americans. Democrats accused them of “hollowness and insincerity” for the causes of black men, claiming Republicans were only looking after “partisan considerations.”

In the late afternoon, on February 25th, the vote was taken, and Democrats lost, 48 yays to 8 nays. The Times credited Revels for remaining dignified even though “the abuse which had been poured upon him and on his race during the last two days might well have shaken the nerves of anyone.” He took an oath of office, took his seat, and the Senate was adjourned for the weekend.

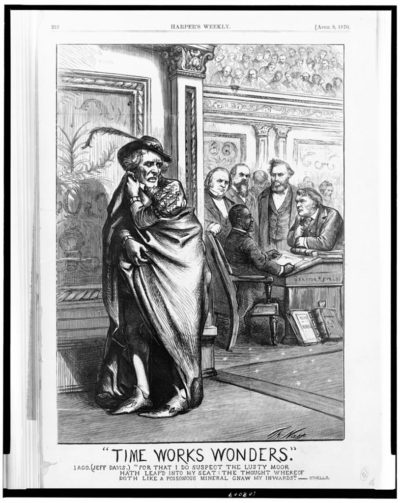

Of the two Mississippi Senate seats filled in that session, one had been most recently occupied by Jefferson Davis, the president of the Confederacy during the Civil War. Harper’s Weekly ran a political cartoon by Thomas Nast that featured Davis as Iago, the traitorous villain of Shakespeare’s Othello, looking on at Revels taking his place in the chamber: “For that I do suspect the lusty moor hath leap’d into my seat: the thought whereof doth like a poisonous mineral gnaw my inwards.”

Revels only served in the U.S. Senate for about a year. Toward the end of his term, on February 8, 1871, Revels sat on the Committee on the District of Columbia as it heard arguments over a clause that would have effectively desegregated D.C. schools. Senator Revels addressed the committee, arguing against an amendment to strike the clause, saying, “If the nation should take a step for the encouragement of this prejudice against the colored race, can they have any ground upon which to predicate a hope that Heaven will smile upon them and prosper them?” He spoke about the oppression of African Americans all over the country that continued because of segregation in housing, church, transportation, and education, and he pleaded his fellow senators to consider how desegregated schools could help to empower African Americans “without one hair upon the head of any white man being harmed.” Unfortunately, his side lost the vote, and school segregation remained lawful in Washington, D.C. until 1954.

Revels was the first in a small wave of black southern congressmen during the Reconstruction Era. A few years after his term, another African American — Blanche Bruce — was elected to the Mississippi Senate. Bruce was able to serve a full term, but Mississippi hasn’t elected an African-American U.S. senator since. In fact, only ten have served in the history of the country.

Featured image: Hiram Revels, the first African American to serve as a U.S. senator. (Library of Congress / Brady Handy Photograph Collection)