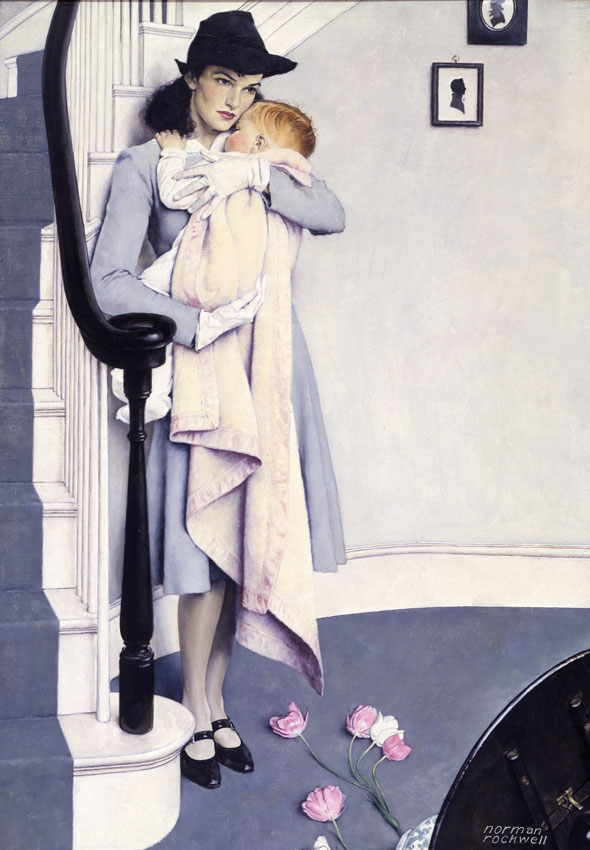

‘Red Head’ by Norman Rockwell

Every day is Mother’s Day. None of us would be here without them!

For some of us whose mothers are no longer here, it is a wistful time. Yet, they are still with us. She is there in the daffodils and crocuses she planted years ago that rise out of the ground every year to welcome the spring. Your mother is there in the music you shared — perhaps that special song she sang just for you at bedtime. They will always be here, part of the fabric of our beings and lives. Even the mothers who were not able to be present and available to their children because of difficulties — they play a part in forming you, teaching you to seek out what is missing and go on a journey to find it, no matter what.

I stumbled upon this striking painting of my grandfather’s a few weeks ago. I chose this image specifically for Mother’s Day because it is not remotely sentimental — something my grandfather is frequently accused of being. It is simply a masterfully executed illustration of maternal care. It’s entitled Red Head — an illustration for a story of the same name by Brooke Hanlon that appeared in American Magazine in November 1940:

“No doubt Linda had meant to hold young Tim gingerly, fearfully, but that sort of holding was never part of young Tim’s plans …”

Story illustration for American Magazine, November 1940.

Oil on canvas, 37 1/8″ x 26″.

National Museum of American Illustration collection.

© Norman Rockwell Family Agency. All rights reserved.

Red Head is a stunning study of black, white, and gray tones — gradations of gray — with the only flashes of color being the bright pink of the tulips on the floor, the delicate red of the boy’s hair, the blush tone of the blanket and the deep rose of her lips. There is a coldness to the palette.

The woman, quite rigid, is softened by the little boy in her arms and the awakening of her innate need to protect and nurture him. The choice of hat is fascinating — a fedora that is almost masculine, yet there’s something elfin in its shape. It reminds me of a hat Garbo once wore in a film. It adds to the guarded quality about her. The profile of the hat reflects the silhouettes of the cameo portraits on the wall. Cameos reveal just so much, only a profile, mirroring her somewhat masked emotional state. The magic of the painting is that it is static but very much alive — this is a turning point in this woman’s life, a softening, a shift. The overturned table and scattered flowers illuminate this. The empty stairs reaching upward with the swirling banister indicate movement, rising above the circumstances below.

Norman Rockwell would try out new techniques throughout his career — to stay current, to try to avoid his paintings registering as outdated. Al Parker, known as the Dean of Illustrators, led a new wave of illustrators in the 1930s, including Coby Whitmore and Jon Whitcomb. My grandfather employed some of the techniques from this school — the stark contrast of colors, the pronounced use of white and pastels — to try to keep up with the young upstarts! I personally love the wedding of opposites in the painting, the starkness married with the awakening tenderness — moving beyond the tumbled past into something with promise and possibility.

Warmest wishes and gratitude to all moms,

Abigail