The Red Sox, Cooperstown, and Firefighters: The Story of Ted Williams’ Ego

Sure, Ted Williams was big-headed, but if he didn’t believe in himself, who would?

This article and other features about baseball can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition, Baseball: The Glory Years. This edition can be ordered here.

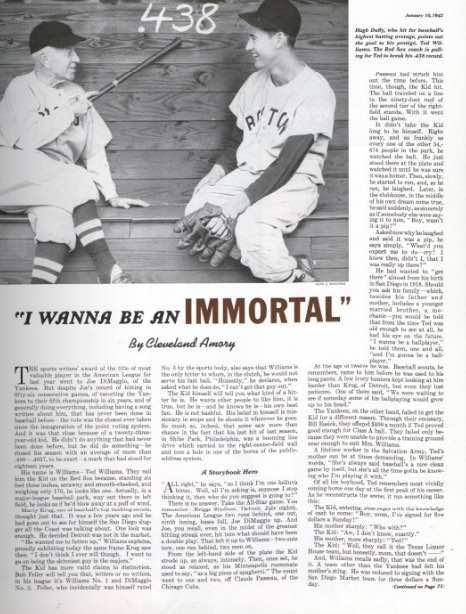

His name is Williams — Ted Williams. They call him the Kid on the Red sox because, standing 6 feet 3 inches, scrawny and smooth- cheeked, and weighing only 170, he looks like one. actually, in a major-league baseball park, way out there in left field, he looks as if he’d blow away at a puff of wind.

The Kid himself will tell you what kind of a hitter he is. He wants other people to like him, it is true, but he is — and he knows he is — his own best fan. He is not bashful. His belief in himself is missionary in scope and he shouts it wherever he goes. so much so, indeed, that some saw more than chance in the fact that his last hit of last season, in Shibe Park, Philadelphia, was a booming line drive which carried to the right-center-field wall and tore a hole in one of the horns of the public-address system.

“All right,” he says, “so i think i’m one helluva hitter. Well, all i’m asking is, suppose i stop thinking it, then who do you suggest is going to?”

There is no answer.

— “I Wanna Be an Immortal” by Cleveland Amory, Jan. 10, 1942

The Designated Hitter Debate

We wanted to do justice to the complexities of the Designated Hitter Rule, so we asked two Post staff members—both baseball fans—to take opposing sides in the debate. We found their exchange enlightening—and amusing.

(Batting for the “Pro” side is Aaron Rimstadt)

Pro 1. Fans like home runs. Purist may enjoy watching intricate, defensive games, but casual fans, kids, and people who put together highlight reels love homers. DH’s provide them the fireworks they want in a game.

(The “Con” is handled by Kelsey Roan)

Con 1: Fans may love a homer, but fans also love a stolen base, and the National League (the one without Designated Hitters) has more of the latter on average. National League hitters—including pitchers—are not willing to waste energy on a slim chance to fire the ball out of the park. Instead, they wisely choose to slap smart hits into the field and run them out. Designated Hitters and other big sluggers are slow and cumbersome. Base hitters are crafty and fast, making energetic leaps and dusty slides to get their base. Call me a purist, but that’s more enjoyable baseball than watching a bulky, overpaid old player hitting another home run.

Pro 2. Great Designated Hitters like David Ortiz, Frank Thomas, Paul Moliter, Harold Baines, Carl Yastrzemski. ‘Nuff said.

Con 2: Don Drysdale, Rick Wise, Greg Maddux, Roger Clemens, Cy Young, BABE RUTH. That’s right, we’ve got the Babe himself.

Pro 3. Who wants to see a bad hitter hopelessly flail at the ball? Or watch a good hitter get intentionally walked because the pitcher knows he can strike out the opposing pitcher who is up next?

Con 3: Who wants to see a good hitter hopelessly flail at a ball? Sluggers are considerably more likely to strike out swinging, because they will swing at anything that looks right—and there are many pitches in even a mediocre pitcher’s arsenal that exist only to trick the eye. (Also, people love to argue that pitchers can’t hit, but a DH can’t field for beans. I, for one, prefer to see smart fielding than big hitting.)

Pro 4. The NFL—by far the most popular sports league in America—uses specialized players for offense and defense. Major League Baseball, on the other hand, is struggling with attendance. Why not use specialized players? What’s wrong with a manager utilizing various players’ specific talents?

Con 4: The charm of baseball is that all the players are versatile. Specializing players sucks the soul out of the game. Instead of talking about a great all-around player who hits and fields like a champ, fans find themselves asking “Who’s that? Oh, the guy who bats seventh.”

Pro 5. The DH lets aging stars and fan favorites play a few more years. A 10-time all-star who has lost the quickness needed for fielding can still fill seats with his hitting. In fact, the DH provides a one-two punch for ticket sales. He provides more offense, and he extends the careers of marketable players.

Con 5: It allows aging stars to play well past their primes. Everyone likes to see a big name play, but the best baseball is played by the young guns, who bring fresh enthusiasm and athleticism to the game. An aging star is big and bulky and can no longer run well. Give me a rookie any day.

Con 6: The DH Rule robs managers of a key bit of strategy: the double switch. If the pitcher is due up in a tough patch like the bottom of the ninth with two men on and two outs, the manager can push the pitcher to a different section of the batting order, and move a good hitter into that key segment.

Pro 6. Well, the DH Rule lets managers use a strong hitter instead of waiting to send in a pinch hitter in the ninth inning. In fact, it allows the manager to not have to worry about his worst batter at all.

Con 7: The DH Rule started with the intention of making baseball more flashy and exciting. Yet, there is not a great difference between the stats in the American League, where they use Designated Hitters, and the National League, where the pitcher must take his turn at bat. The American League tends to accumulate more wins in interleague play, but the general stats are inconclusive. If one league has a superiority over the other in any area, the difference isn’t large enough to matter to anyone but the most scrupulous statistician.

Pro 7. The batting averages for the American League have been better than the NL every year between 1973, the year that the DH was instituted, and 2008. In 2009, the three teams with the best batting average (Angels, Yankees, and Twins) were in the AL. So were the top two HR teams (Yankees and Rangers), top three scoring teams (Yanks, Angels, and Red Sox), top four in total hits (Angels, Yankees, Twins, and Blue Jays), top three in RBI’s (Yanks, Angels, and Red Sox), and top three in On-Base Percentage (Yanks, Red Sox, and Angels). Admittedly, the difference in batting averages between the two leagues has been relatively small every year (for example, the AL edged the NL in ’07 with a batting average of .271 versus .266), but the fact that it has done so every year is significant.

Pro 8. The American League has better teams. It won six of the last 10 World Series, and it is hard to believe that the DH didn’t help. The Red Sox might not have won two titles in the past decade without a certain DH known as “Big Papi.” Another all-time great, Frank Thomas, helped the White Sox to their ’05 title as a hit-only player.

Con 8: The American League also has worse teams. They may have the Yankees and Red Sox (which are only as great as they are because they spend outlandish amounts of money for big players), but they also have the Cleveland Indians, the Kansas City Royals and the Oakland A’s. The DH Rule has made the AL a real hit-or-miss league, instead of fostering a strong, stable league. When teams in a league are closer together, there is more excitement because it is not completely clear who will come out on top.

For our last inning, we’ve reversed the batting order.

Con 9: The National League sells more tickets. Isn’t that the whole goal of the Designated Hitter Rule: to bring in more fans? Why is it, then, that the American League doesn’t sell nearly as many tickets as the National League, despite keeping a Designated Hitter at the ready? Maybe it’s that people would rather see baseball than a Home Run Derby. I know I would.

Pro 9: History tells us that the DH actually improved ticket sales. In 1972, the year before the DH rule, nine of the 12 AL teams drew an attendance of less than a million. In ’73, there were only four. Two of those four were over 900,000 (seven AL teams were under 900,000 in ’72). Attendance also went up for the NL in ’73, probably because the new rule created a buzz around the game in general. Considering that teams from the AL have also won more World Series (the AL boasts a 21 to 15 advantage since ’73, including eight of the last 12 champs), they will have benefited from the increased revenue from jersey sales, corporate endorsements, etc.